Abstract

Objectives

To identify associations between frailty and non-response to follow-up questionnaires, in a longitudinal head and neck cancer (HNC) study with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Materials and methods

Patients referred with HNC were included in OncoLifeS, a prospective data-biobank, underwent Geriatric Assessment (GA) and frailty screening ahead of treatment, and were followed up at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after treatment using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 and Head and Neck 35. Statistical analysis for factors associated with non-response was done using Generalized Linear Mixed Models.

Results

289 patients were eligible for analysis. Mean age was 68.4 years and 68.5% were male. Restrictions in Activities of Daily Living [OR 4.46 (2.04–9.78)] and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [OR 4.33 (2.27–8.24)], impaired mobility on Timed Up and Go test [OR 3.95 (1.85–8.45)], cognitive decline [OR 4.85 (2.28–10.35)] and assisted living (OR 5.54 (2.63–11.67)] were significantly associated with non-response. Frailty screening, with Geriatric 8 and Groningen Frailty Indicator, was also associated with non-response [OR, respectively, 2.64 (1.51–4.59) and 2.52 (1.44–4.44)]. All findings remained significant when adjusted for other factors that were significantly associated with non-response, such as higher age, longer study duration and subsequent death.

Conclusion

Frail HNC patients respond significantly worse to follow-up PROMs. The drop-out and underrepresentation of frail patients in studies may lead to attrition bias, and as a result underestimating the effect sizes of associations. This is of importance when handling and interpreting such data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The global incidence of cancer is rapidly increasing, specifically among older populations [1]. Older patients, however, are strongly underrepresented in clinical trials in all fields of medicine [2]. This is the case for large cancer trials, which are important for the establishment of international guidelines, as well [3,4,5]. Barriers for trial inclusion can be raised by the system, by care-providers, but also by patients themselves [6].

Besides the evident difficulty of including older patients in clinical studies, retaining older patients in clinical studies may be difficult as well, and lead to higher non-response and study drop-out [7, 8]. This may be referred to as ‘attrition’. Especially with the growing use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROM’s), the risk of non-response is lurking, and this may be even more the case in the older and frail population [9]. PROM’s, however, such as questionnaires for quality of life (QoL), are increasingly being recognized as important outcome measures, besides recurrence or survival alone. Specifically for older patients this may be the case, as they may prioritize outcomes such as QoL over length of life, for example [10].

Yet, the occurrence of non-response and study drop-out for older and frail patients relative to their younger and fit counterparts is important to know. Systematic loss of patients from specific study groups may lead to attrition bias [11]. Consequences of this may be under- or overestimating outcomes, misinterpretation of the results and poor generalizability.

The age of patients with head and neck cancer averages around 65 and the burden of geriatric deficits and therewith frailty is large in this population, compared to patients with other solid malignancies [12]. The risk of introducing bias into studies may therefore be high. In our previous studies we encountered that frail patients were more difficult to include because of their poor response to baseline questionnaires [13]. Therefore, the goal of the current study was to investigate whether frail patients exhibit more non-response than non-frail patients to follow-up questionnaires and whether specific items of a routinely performed geriatric assessment (GA) are associated with non-response.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study covers a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from the longitudinal observational Oncological Life Study (OncoLifeS), a large hospital-based oncological data-biobank at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Groningen, The Netherlands [14]. OncoLifeS is approved by the Institutional Review board of the UMCG, this study was approved by the scientific committee of OncoLifeS. In OncoLifeS patients are included after providing written informed consent. Between October 2014 and May 2015, all patients referred with (suspicion of) primary or recurrent cancer in the head and neck area (mucosal, salivary gland and cutaneous) were consecutively included. Patients were seen at the outpatient clinic of the departments of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Radiation Oncology. Patients underwent a GA, including frailty screening, at baseline, before treatment. Patients were excluded from the analysis when initially palliative or non-standard treatment was conducted or when patients did not return the baseline questionnaires. Also, data of patients were excluded when recurrence or death occurred during follow-up, from that moment onward. Patients were followed up during 2 years after treatment using QoL questionnaires (see Follow-up).

Patient, tumour and treatment characteristics

Patient, tumour and treatment characteristics were withdrawn from the OncoLifeS data-biobank. Disease was staged according to the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control’s TNM Classification [15].

Baseline assessments

Before treatment patients underwent GA, including a frailty screening and assessment of the somatic, functional, psychological and socio-environmental domains. Somatic assessments included scoring of the 27-item Adult Comorbidity Evaluation (ACE-27), polypharmacy (5 or more medications) and the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) [18,19,20]. Functional assessments were Activities of Daily Living (ADL), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and the Timed Up & Go (TUG) with a cut-off at 13.5s [21,22,23,24]. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) were used for the psychological assessments [25,26,27]. Marital status, living situation and educational level assessed for the socio-environmental domain and were registered as part of a standardized questionnaire. Frailty screening consisted of the Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI) and Geriatric 8 (G8) questionnaires [16, 17].

Follow-up

Patients were followed up using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Head and Neck 35 (EORTC-QLQ-HN35) at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after treatment. Follow-up was conducted by sending and returning questionnaires by mail (dept. of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, dept. of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery) or by filling out questionnaires at the outpatient clinic (dept. of Radiation Oncology). This difference between methods was incorporated as a variable in the dataset.

Outcome

Non-response was defined as both complete QoL questionnaires missing in the dataset. This was recalculated to a binary outcome (yes/no) for each of the follow-up moments (3, 6, 12 and 24 months) after treatment initiation, regardless of the previous outcomes, and until recurrence or death occurred.

Statistical analysis

All statistical procedures were performed with SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM). Descriptive statistics are presented as n (%) unless specified otherwise. Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) were used to calculate odds ratios of the association between frailty and non-response for any data point in the follow-up. As an advantage, this allows for using all data points before exclusion due to death or recurrence and thus reducing risk of bias. Patients with upcoming (but not yet diagnosed) recurrence or death may have worse response; therefore, ‘subsequent recurrence’ and ‘subsequent death’ tested as variables as well. For all models, non-response was the target variable in a binary logistic fashion. For fixed effects an intercept and the predictor variable were included. For random effects an intercept was included and covariance type was set to unstructured. At first, GLMMs were carried out for patient characteristics, both univariate and in a multivariable model. Second, frailty screening instruments and GA items were evaluated in a GLMM, both in an unadjusted model and then in a model adjusted for all relevant patient characteristics.

Results

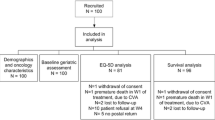

During the study period, 369 patients with mucosal, salivary gland and cutaneous malignancies in the head and neck area were included in OncoLifeS. After exclusion of patients receiving palliative or non-standard treatment and patients not responding to baseline questionnaires, 289 patients remained in the study for analysis (Fig. 1). The mean age was 68.4 years and 68.5% were male. 54.5% of patients had advanced stage disease. Recurrence, death and response to follow-up questionnaires are shown in Fig. 2. From all patient and study characteristics, age [OR 3.21 (1.80–5.72)], time [per year OR 1.47 (1.10–1.97)] and subsequent death [OR 2.84 (1.62–4.99)] were significantly associated with non-response to follow-up questionnaires, in univariate GLLMs (Table 1). All remained significant in the multivariable model (Table 1).

Regarding GA items, restrictions in ADL [OR 4.46 (2.04–9.78)], IADL [OR 4.33 (2.27–8.24)], impaired mobility on the TUG [OR 3.95 (1.85–8.45)], signs of cognitive decline on the MMSE [OR 4.85 (2.28–10.35)], assisted living or living in a nursing home [OR 5.54 (2.63–11.67)] were significantly associated with non-response to questionnaires in univariate GLLMs (Table 2). This remained the case after adjusting for patient and study characteristics that showed significance in the univariate model, such as age, time and subsequent death (Table 2).

Frailty screening by both G8 and GFI, was significantly associated with non-response [OR respectively 2.64 (1.51–4.59) and 2.52 (1.44–4.44)], even after adjusting for the abovementioned factors (Table 2).

Discussion

In this longitudinal observational study, we investigated whether frail patients exhibit more non-response to follow-up questionnaires than non-frail patients and whether specific items of a routinely performed GA are associated with this. Main findings were that frailty screening tools were associated with worse response to follow-up questionnaires. Besides, impaired ADL and IADL, restricted mobility, cognitive decline and dependent living situation were specifically associated with poorer response to follow-up questionnaires. These associations were independent of other significant factors, such as age, duration of the study and subsequent death during the study. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the association between geriatric factors and response to PROMs in patients with HNC. These results are important for the interpretation of all studies dealing with PROMS, because of the increasing proportion of older and frail patients.

In our study, higher age was significantly associated with non-response during follow-up. This is in line with some earlier studies [8, 28,29,30]; however, other studies found no significant differences [9, 31,32,33]. Comparison is difficult, given the different cancer types (and therewith age groups) and study methodologies which may explain the divergent outcomes.

A recent study, however, did investigate study retention and attrition in a longitudinal study of HNC patients in the Netherlands, collecting PROMs, fieldwork data and biobank materials up to 2 years [34]. In this study, age was not associated with attrition, unlike other factors such as higher tumour stage, poorer physical performance and worse comorbidity score. The latter, comorbidity, was in line with other studies [28, 30, 32]; however, not with our study which identified no significant differences in response between patients with none to mild and moderate to severe comorbidities. A reason for this may be the fact that other studies often assign patients with recurrent disease and even deceased patients to the attrition or non-response group as well. In this way, there is a risk of predicting death or recurrence rather than non-response due to other (geriatric) factors. In our study, we have excluded patients with recurrence or death from the analyses, from the moment that recurrence or death occurred. This gives superior understanding underlying non-response mechanisms.

Other items of GA or frailty screening with respect to non-response, drop-out or attrition have rarely been investigated and not at all in the unique population of HNC. In other studies, the most valuable data available is originating from the PROMs themselves that patients were asked to fill out, but then used at baseline as a predictor for drop-out. Among some different studies in other cohorts, poor functional status, symptom burden, depressive symptoms, cognitive failure, psychosocial symptoms, lower socioeconomic status, low educational level, and poor baseline QoL were associated with attrition [9, 29, 31,32,33]. It must be noted that study methodology differed greatly between studies, and none of the studies specifically aimed HNC. Besides, one may question the ability of a QoL questionnaire subscale to diagnose, e.g. ‘cognitive failure’, often based on just a few questions, compared to specifically developed screening tools such as MMSE in the case of cognition. In our current study, where we have employed well-known and frequently used instruments for GA (and not subscales of the PROMs), we have seen consistent associations of restricted ADL and IADL, poor mobility, cognitive decline and dependent living situation with non-response.

Frailty screening tools, such as the G8 and GFI, were significantly associated with increased non-response as well, which was also expected given the share of functional, cognitive and psychosocial items in the screening tools. This is in line with another study, in which frailty was significantly associated with drop-out from a cohort study [35].

Attrition is common in longitudinal studies, especially with the use of PROMs. When data are missing (completely) at random, this usually does not lead to bias. However, when attrition rates are distinct for different study groups, e.g. in this case when comparing frail to non-frail patients, this may introduce attrition bias [36]. Data may be not missing at random anymore, as for instance frail patients systematically respond worse to the questionnaires and may have different outcomes as well. In such studies, such as in studies evaluating QoL outcomes between frail and non-frail patients [37, 38], the observed differences may be an underestimation of the real difference. Although ideally this should be prevented ahead of time by creating a strategy to take care of frail patients at risk for dropping-out (e.g. alternative study visits, using patients peer support, supportive telephone contacts) [39], it is important to know how to handle and interpret these data. According to experts, mixed models remain the best choice for the analysis of repeated measures and longitudinal data [36].

Strengths of this study include the prospective inclusion of patients, the large range of validated screening instruments, the ability to adjust for relevant covariates such as subsequent death or recurrence and study characteristics, and the maximum use of data points using mixed models and therewith limiting bias as much as possible. Limitations of this study may be the different collection methods of PROMs between departments (which was adjusted for), the absence of information why patients dropped out, the relatively small and heterogeneous study cohort, which included both mucosal as cutaneous malignancies. Besides, by excluding patient not responding to baseline questionnaires, some form of bias may already be present from the beginning.

Conclusion

Frailty, measured by deficiencies on GA, such as impaired ADL and IADL, restricted mobility, cognitive decline and dependent living situation, or by frailty screening instruments (G8 and GFI), is significantly associated with worse response to follow-up PROMs. This is of importance when handling and interpreting data on older or frail HNC patients, as with the resulting attrition bias the observed effects may be an underestimation of the real differences. Not only researchers but also clinicians need to be aware of this potential bias during the interpretation of studies dealing with PROMs, as the frailest patients are less likely to be included and more likely to be lost from follow-up.

References

Pilleron S, Sarfati D, Janssen-Heijnen M et al (2019) Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 144(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31664

Herrera AP, Snipes SA, King DW, Torres-Vigil I, Goldberg DS, Weinberg AD (2010) Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am J Public Health 100(Suppl 1):S105–S112. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.162982

Singh H, Kanapuru B, Smith C et al (2017) FDA analysis of enrollment of older adults in clinical trials for cancer drug registration: a 10-year experience by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Oncol 35(15_suppl):10009. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.10009

Scher KS, Hurria A (2012) Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol 30(17):2036–2038. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6727

Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP et al (2003) Participation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 21(7):1383–1389. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.08.010

Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ et al (2021) Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: a systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin 71(1):78–92. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21638

Chatfield MD, Brayne CE, Matthews FE (2005) A systematic literature review of attrition between waves in longitudinal studies in the elderly shows a consistent pattern of dropout between differing studies. J Clin Epidemiol 58(1):13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.05.006

Roick J, Danker H, Kersting A et al (2018) Factors associated with non-participation and dropout among cancer patients in a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12645

Gebert P, Schindel D, Frick J, Schenk L, Grittner U (2021) Characteristics and patient-reported outcomes associated with dropout in severely affected oncological patients: an exploratory study. BMC Med Res Methodol 21(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01259-0

Shrestha A, Martin C, Burton M, Walters S, Collins K, Wyld L (2019) Quality of life versus length of life considerations in cancer patients: a systematic literature review. Psychooncology 28(7):1367–1380. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5054

Nunan D, Aronson J, Bankhead C (2018) Catalogue of bias: attrition bias. BMJ Evid-Based Med 23(1):21–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2017-110883

Bras L, Driessen DAJJ, de Vries J et al (2019) Patients with head and neck cancer: are they frailer than patients with other solid malignancies? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13170

Bras L, de Vries J, Festen S et al (2021) Frailty and restrictions in geriatric domains are associated with surgical complications but not with radiation-induced acute toxicity in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study. Oral Oncol 118:105329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105329

Sidorenkov G, Nagel J, Meijer C et al (2019) The OncoLifeS data-biobank for oncology: a comprehensive repository of clinical data, biological samples, and the patient’s perspective. J Transl Med 17(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-2122-x

Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C (2009) TNM classification of malignant tumours, 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford

Schuurmans H, Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Frieswijk N, Slaets JPJ (2004) Old or frail: what tells us more? J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(9):M962–M965. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.9.M962

Delva F, Bellera CA, Mathoulin-Pélissier S et al (2012) Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol 23(8):2166–2172. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr587

Piccirillo JF (2000) Importance of comorbidity in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110(4):593–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200004000-00011

Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G, Mohile SG, Holmes HM (2016) Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol 7(5):346–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.07.010

Elia M. The “MUST” Report. Nutritional Screening for Adults: A Multidisciplinary Responsibility. Development and Use of the “Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool” (MUST) for Adults. British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN); 2003.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW (1963) Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185(12):914–919. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016

Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9(3):179–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179

Podsiadlo D, Richardson S (1991) The timed “up & go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 39(2):142–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x

Barry E, Galvin R, Keogh C, Horgan F, Fahey T (2014) Is the Timed Up and Go test a useful predictor of risk of falls in community dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta- analysis. BMC Geriatr 14(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-14

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

van der Cammen TJ, van Harskamp F, Stronks DL, Passchier J, Schudel WJ (1992) Value of the Mini-Mental State Examination and informants’ data for the detection of dementia in geriatric outpatients. Psychol Rep. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3.1003

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA (1986) Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 5(1–2):165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

Spiers S, Oral E, Fontham ETH et al (2018) Modelling attrition and nonparticipation in a longitudinal study of prostate cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol 18(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0518-6

Ramsey I, de Rooij BH, Mols F et al (2019) Cancer survivors who fully participate in the PROFILES registry have better health-related quality of life than those who drop out. J Cancer Surviv 13(6):829–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00793-7

Fosså SD, Dahl AA, Myklebust TÅ et al (2020) Risk of positive selection bias in longitudinal surveys among cancer survivors: lessons learnt from the national Norwegian Testicular Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol 67:101744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2020.101744

Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, Yennu S, Bruera E (2013) Attrition rates, reasons, and predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology clinical trials. Cancer 119(5):1098–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27854

Perez-Cruz PE, Shamieh O, Paiva CE et al (2018) Factors associated with attrition in a multicenter longitudinal observational study of patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 55(3):938–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.11.009

Renovanz M, Hechtner M, Kohlmann K et al (2018) Compliance with patient-reported outcome assessment in glioma patients: predictors for drop out. Neuro-Oncology Pract 5(2):129–138. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npx026

Jansen F, Brakenhoff RH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ et al (2022) Study retention and attrition in a longitudinal cohort study including patient-reported outcomes, fieldwork and biobank samples: results of the Netherlands quality of life and Biomedical cohort study (NET-QUBIC) among 739 head and neck cancer patients and. BMC Med Res Methodol 22(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01514-y

Ohyama S, Hoshino M, Takahashi S et al (2021) Predictors of dropout from cohort study due to deterioration in health status, with focus on sarcopenia, locomotive syndrome, and frailty: from the Shiraniwa Elderly Cohort (Shiraniwa) study. J Orthop Sci 26(1):167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jos.2020.02.006

Bell ML, Kenward MG, Fairclough DL, Horton NJ (2013) Differential dropout and bias in randomised controlled trials: when it matters and when it may not. BMJ 346:e8668. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8668

de Vries J, Bras L, Sidorenkov G et al (2020) Frailty is associated with decline in health-related quality of life of patients treated for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol 111:105020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105020

de Vries J, Bras L, Sidorenkov G et al (2021) Association of deficits identified by geriatric assessment with deterioration of health-related quality of life in patients treated for head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 147(12):1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.2837

Pitkala KH, Strandberg TE (2022) Clinical trials in older people. Age Ageing 51(5):afab282. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab282

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JAL declared receiving Grants from the European Union and Dutch Cancer Society, receiving consulting fees and honorarium from IBA, paid to UMCG Research BV, receiving research grants from IBA, RaySearch, Elekta, Mirada and Siemens, serving in the monitoring or advisory board of UMCN, IBA and RaySearch, and serving as chair of the NVRO. The other authors reported no disclosures.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This study [the Oncological Life Study (OncoLifeS)], a large hospital-based oncological data-biobank at the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Groningen, The Netherlands, OncoLifeS has been approved by the medical ethics committee of the UMCG (no. 2010/109) and has been ISO certified (9001:2008 Healthcare). It was registered in the Dutch Trial Register under the number: NL7839.

Informed consent

Patients were included after obtaining written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Vries, J., Vermue, D.J., Sidorenkov, G. et al. Head and neck cancer patients with geriatric deficits are more often non-responders and lost from follow-up in quality of life studies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 281, 2619–2626 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08528-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-024-08528-w