Abstract

Introduction

Epidural anesthesia is a well-established procedure in obstetrics for pain relief in labor and has been well researched as it comes to cephalic presentation. However, in vaginal intended breech delivery less research has addressed the influence of epidural anesthesia. The Greentop guideline on breech delivery states that there’s little evidence and recommends further evaluation.

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare maternal and neonatal outcomes in vaginally intended breech deliveries at term with and without an epidural anesthesia.

Design

This study was a retrospective cohort study.

Sample

This study included 2122 women at term with a singleton breech pregnancy from 37 + 0 weeks of pregnancy on and a birth weight of at least 2500 g at the obstetric department of University hospital Frankfurt from January 2007 to December 2018.

Methods

Neonatal and maternal outcome was analyzed and compared between women receiving “walking” epidural anesthesia and women without an epidural anesthesia.

Results

Fetal morbidity, measured with a modified PREMODA score, showed no significant difference between deliveries with (2.96%) or without (1.79%; p = 0.168) an epidural anesthesia. Cesarean delivery rates were significantly higher in deliveries with an epidural (35 vs. 26.2%, p = 0.0003), but after exclusion of multiparous women, cesarean delivery rates were not significantly different (40.2% cesarean deliveries with an epidural vs. 41.5%, p = 0.717). As compared to no epidurals, epidural anesthesia in vaginal delivery was associated with a significantly higher rate of manual assistance (33.8 versus 52.1%) and a longer duration of birth (223.7 ± 194 versus 516.2 ± 310 min) (both p < 0.0001)".

Conclusion

Epidural anesthesia can be offered as a safe option for pain relief without increasing neonatal or maternal morbidity and mortality. Nevertheless, it is associated with a longer birth duration and manually assisted delivery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Epidural anesthesia can be offered as a safe option for pain relief for women attending vaginal breech birth without increasing neonatal or maternal morbidity or mortality. Also, cesarean delivery is not associated with an epidural anesthesia. Women should be informed that epidural anesthesia is associated with manually assisted delivery and a prolonged first and second stage of labor. |

Introduction

Regional anesthesia is a well-established procedure in obstetrics for pain relief in labor and is broadly recommended in guidelines [1]. A Cochrane review including data of 40 trials and over 11.000 women shows a higher chance of instrumental assisted delivery in trials before 2005, an effect that did not occur when trials before 2005 were excluded from the analysis. No difference was shown concerning neonatal outcome or the rate of cesarean delivery [2].

In deliveries with breech presentation evidence is scarce regarding the safety and effect of epidural anesthesia and recommendations are vague: the British Greentop guideline states that the effect of an epidural anesthesia on the success of vaginal breech birth is unclear and might increase the risk of intervention and recommends further research [3]. The French clinical practice guideline emphasizes the high level of evidence for epidural anesthesia in cephalic version, with no higher risk of cesarean or risk of vaginally assisted delivery and therefore encourages the use of epidural anesthesia in breech presentation [4]. The SOGC (Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada) clinical practice guideline on breech delivery recommends avoiding dense epidural to maximize expulsive efforts, while neither ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) nor RANZCOG (Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) addresses the issue of epidural anesthesia [5,6,7].

In the term Breech trial epidural anesthesia was not associated with adverse perinatal outcome [8,9,10]. The PREMODA (PREsentation et MODe d'Accouchement) trial does not report an impact of epidural anesthesia [11]. Even though safety of epidural anesthesia is established, there still are reports of associated increased adverse neonatal outcome, prolonged labor, or cesarean delivery rate [12,13,14].

In the FRABAT (FRAnkfurt Breech At Term Study Group) cohort, the demand for epidural analgesia was high, especially in primiparous women [15]. Thus, it can be assumed that the patients’ need for an epidural anesthesia during an intended vaginal breech birth is high and clinicians will be confronted with this topic frequently during clinical counseling.

Since every medical intervention with its possible complications should be discussed with patients before administration, it is mandatory to gain evidence in order to be able to give reliable information. The effect of epidural analgesia on vaginally intended birth out of breech presentation has not been elucidated properly because the respective recommendations are adopted from vertex presentations. We present a cohort study on the neonatal and maternal outcome in vaginally intended breech deliveries in light of the use of an epidural anesthesia. We hypothesize that an epidural anesthesia does not influence perinatal morbidity in vaginally intended breech deliveries provided the epidural keeps the motor function and patients are not immobilized.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a single center cohort study in all pregnant women at term (≥ 37 weeks of gestation) presenting with a breech presentation at the Goethe University Hospital Frankfurt, Germany, from January 2004 to December 2018. The analysis was performed in a retrospective manner through generating subgroups (deliveries with or without an epidural) within our study cohort.

The university hospital’s ethics committee gave consent (420/11). All data were assessed through the in-house patient data system as well as the Hessen Perinatalerhebung and were acquired after patient’s dismissal from the hospital. All patients received the standard clinical care. Because of the retrospective nature of data acquisition, the ethics committee waived an informed patient’s consent.

Exclusion criteria were fetal birth defect, uterine malformation, multiple pregnancies, contraindication for an epidural anesthesia, estimated birth weight less than 2500 g, and contraindications for vaginal approach.

Other studies with intersection cohorts have been published by different authors of the FRABAT group within previous publications. [15,16,17,18,19].

Clinical procedure and counseling

All pregnant women with a breech presentation are counseled between 34 and 36 weeks of gestation. External cephalic version, vaginal attempted birth, as well as cesarean delivery are discussed with each patient, depending on the individual patient history and examination. During vaginal delivery, which is performed predominantly in an upright maternal position, manual assistance to deliver the arms or the fetal head is performed by a trained physician if necessary. A maternal upright position applies when the mother stands or is on all fours (hands and knees). An epidural is offered to every woman by their own choice if no contraindications (e.g., thrombocytopenia) are present. Counseling specifics and details on manual assistance in the upright maternal position have been published [17, 20]

Outcome parameters

Primary outcome was perinatal fetal morbidity, which was assessed using the modified PREMODA Score, potentially associated with the delivery mode. The PREMODA Score is adapted from the PREMODA study [11] implies NICU stay > 4 days, trauma at birth, neurological deficits, intubation > 24 h, or an APGAR score of less than 4 at 5 min [9]. Secondary outcome measures were duration of labor, rate of cesarean delivery, and rate of assisted vaginal delivery.

Method of epidural anesthesia

Epidural anesthesia was administered by an in-house anesthesiologist. It was initiated with a dose of Ropivacaine and Sufentanil. After the loading dose, a patient controlled pump with Ropivacaine / Sufentanil was connected to maintain persistent pain reduction. Patients were not immobilized and the rate could be reduced if necessary. If analgesia was not sufficient patients could receive up to three additional boli per hour.

Statistical analysis

Groups of variables were tested for normal distribution with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test [21]. Group differences were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 testing. Student’s T-test was utilized to compare continuous variables [22, 23]. A nominal logistic regression analysis with Wald testing was performed.[24] We used JMP 14.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for our analyses. A p-value of below 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

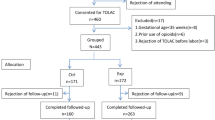

Of the 2122 women presenting for counseling with breech presentation at our center, 1413 attempted vaginal delivery.

744/1413 (52.7%) women received an epidural anesthesia (EPI group), 669/1413 (47.3%) did not (NEPI group, Table 1). Patients in the NEPI group were significantly older than patients in the EPI group (NEPI 32.7 (± 4.5), EPI 31.9 (± 4.3) p = 0.0009). BMI was equally distributed between both groups (Table 1). There were significantly more primiparous women in the EPI group (EPI 523, 70.3%; NEPI 316, 47.2%; p < 0.0001; Table 1). Mean birth weight was significantly higher in the EPI group (3388 g; NEPI: 3323 g; p = 0.002; Table 1). Duration of pregnancy was significantly longer in the EPI group (280 days) as compared to the NEPI group (278 days, p > 0.0001; Table 1).

There were significantly more manually assisted vaginal deliveries when women received an epidural anesthesia: In the NEPI group 327/669 (48.9%) women delivered vaginally, while 167/669 (25.0%) delivered with manual assistance. In the EPI group 232/744 (31.2%) women delivered spontaneous and 252/744 (33.9%) with assistance (p < 0.0001). Cesarean delivery after onset of labor was performed in 175/669 (26.2%) in the NEPI group which is significantly less often than in the EPI group (260/744 (35.0%), p = 0.0003, Table 1 and Fig. 1).

We investigated all vaginal deliveries in a sub-cohort analysis. There were significantly more primiparous women in the group of patients giving vaginal birth with an epidural anesthesia (vEPI group, n = 313, 64.7%) as compared to primiparous women without an epidural anesthesia (vNEPI group, n = 185, 37.5%; p < 0.0001, Table 2). Birth weight was not significantly different between vNEPI group (3307 ± 340 g) and vEPI group (3325 ± 391 g; p = 0.361; Table 2). Duration of labor was significantly longer in vaginal deliveries with an epidural anesthesia as compared to vaginal deliveries without epidural anesthesia (vEPI 516 ± 310 min; vNEPI 224 ± 194 min; p < 0.0001, Table 2). Manual assistance was significantly more often necessary in vaginal deliveries with an epidural anesthesia (vEPI: n = 252, 52.1%; vNEPI: n = 167 33.8%; p < 0.0001, Table 3). Fetal morbidity measured with the modified PREMODA score was not significantly different between both groups (vNEPI: 2.02%, vEPI: 3.31%; p = 0.2373; Table 2). There was no significant difference in high grade perineal tears between groups (vNEPI: n = 8; 1.6%, vEPI: n = 10; 3.3%, p = 0.642; Table 2), but perineal tears of all degrees were significantly more often in vaginal deliveries with an epidural anesthesia (vNEPI: n = 224; 45.3%, vEPI: n = 249; 51.4%, p = 0.0056; Table 2).

We investigated a subgroup of primiparous women (n = 839). In the group of primiparous women with an epidural anesthesia (pEPI) birth weight was significantly higher as compared to deliveries of primiparous women without an epidural anesthesia (pNEPI: 3253 ± 411 g, pEPI: 3379 ± 416 g; p < 0.0001, Table 3). Cesarean delivery rate was not significantly different between groups in this sub-analysis (pNEPI: n = 131; 41.5%, pEPI: n = 210; 40.2%; p = 0.7174, Table 3). In primiparous women, there was no significant difference in the modified PREMODA score whether patients received an epidural or not (pNEPI: n = 5; 1.58%, pEPI: n = 20 3.82%; p = 0.0917, Table 3).

Within a multiple nominal logistic regression analysis, maternal age, birth weight, neonatal morbidity, and cesarean delivery were not significantly associated with an epidural anesthesia (Table 4). In contrast, primiparity (OR 2.295; 95% CI: 1.781–2.956; p < 0.0001) and pregnancy duration (OR 1.316; 95% CI: 1.182–1.465; p < 0.0001) were significantly associated with an epidural anesthesia (Table 4).

In the subgroup of vaginal deliveries, only duration of birth (OR 1.0055; 95% CI: 1.0044–1.0066; p < 0.0001) and manually assisted delivery (OR 2.23; 95% CI: 1.57–3.52; p < 0.0001) were significantly increased, whereas perineal injuries were not affected (Table 4).

Discussion

Evidence is scarce on the impact of an epidural anesthesia in vaginally intended breech deliveries since all recommendations are based on studies investigating epidural analgesia in cephalic deliveries. We have performed a cohort study on vaginally intended breech deliveries analyzing the effect of epidural anesthesia on perinatal outcome.

Perinatal morbidity was not significantly different between deliveries with and without epidural anesthesia (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). Furthermore, Goffinet et al. [11] showed that increased short-term morbidity in breech deliveries did not translate into long-term morbidity. Primiparous women were analyzed separately because parity has an impact on delivery outcome measures. In our sub-cohort analyses of primiparous women (Table 3) and a nominal logistic regression model (Table 4), we were able to confirm the data seen in our whole cohort analyses concerning fetal morbidity. Here, PREMODA scores were consistently not different between deliveries with and without epidural anesthesia.

Patients receiving an epidural anesthesia had a higher probability for cesarean delivery after onset of labor in our main cohort (Table 1). But when only primiparous women were analyzed, cesarean delivery rates were not significantly different (Table 3). Also, a nominal logistic regression analysis found no association of cesarean delivery rate and epidural anesthesia (Table 4). The effect on cesarean delivery rates thus derives from the influence of parity. Primiparous women received an epidural anesthesia in 70.3% of cases, multiparous women only in 29.7% (Table 1). This finding contrasts the RCOG guideline; here authors stated that an epidural “might increase the risk of caesarean section”[3]. In vertex deliveries, a Cochrane analysis reports no effect on cesarean delivery rates linked to the use of epidurals [2].

New data suggest that not the epidural anesthesia but a prolonged labor and higher need for pain relief itself pose risk factors for an increased cesarean delivery likelihood; underlying problems are the actual cause rather than the analgesia itself [25].

In vaginal deliveries, the duration of the labor was significantly longer in deliveries with an epidural anesthesia. This effect has also been reported in vertex deliveries [26, 27]. In these studies the immobilization though the application of an epidural is supposedly causative for a longer birth duration. In our center, patients are not immobilized after they receive pain relief by an epidural. This is important because women give birth predominantly in an upright position in order to reduce interventions and newborn morbidity [20]. This is both arguable in vertex and breech presentations. We believe that a “walking” epidural—keeping maternal motor function—is of important benefit for the course of labor: walking and an upright position reduce the duration of labor and the risk of cesarean [28].

Among the patients who delivered vaginally epidural anesthesia was associated with a higher chance of assisted vaginal delivery (see Tables 1, 4). From vertex deliveries we have learned that operative vaginal deliveries are more often performed in deliveries with an epidural anesthesia [26].

When a vaginal operative delivery is indicated because of arrest of birth in active labor, women without an epidural anesthesia might prefer a cesarean section, while women with an epidural anesthesia might feel more equipped for a vaginal operative procedure.

In the cohort of women who experienced a successful vaginal breech delivery, maternal morbidity was not significantly increased in patients with an epidural anesthesia; in particular, we did not find a higher rate of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears or tear of all degrees (Tables 2 and 4). Our data imply that the use of an epidural for patients with a breech presentation undergoing labor is safe and not associated with a higher morbidity – neither for the fetus nor for the mother.

A strength of our study is a large cohort of patients, treated with a standardized protocol. This leads to homogeneity and comparability within our results.

A major limitation of our study is selection bias as all data derive from a single center. This is a retrospective analysis of an existing study cohort. Thus, only associations and not causative relationships can be concluded from our data. A prospective randomized controlled trial would be the gold standard to investigate a clinical intervention. Nevertheless, randomized controlled trials are hardly possible in women with breech delivery and an intention to deliver vaginally since only a few women would accept to stay without pain relief and to withhold an epidural due to a study design would be unethical.

In our data, only the application of an epidural analgesia was documented. The degree of actual pain relief and the time point of administration during labor were not recorded. Duration of pain relief of an epidural analgesia and patient satisfaction are important issues possibly influencing our outcome measures. In future studies, these items should be assessed in order to improve the quality of our results.

However, while the retrospective analysis has limitations, the absence of an influence on perinatal morbidity in our study adds value to the body of knowledge: our data show that mothers will not impact perinatal morbidity by requesting an epidural during labor, contrasting studies by Macharey or Toijonen. In these studies an epidural has been associated with adverse perinatal outcome in breech deliveries [12, 14].

As in vertex presentations, an epidural anesthesia may be offered to ensure pain relief and is a safe gold standard for analgesia during labor. If manual assistance during birth is necessary, a sufficient pain relief might also be beneficial.

Further research in prospective settings would provide a more robust foundation for clinical decision-making and improve the understanding of the impact of epidural anesthesia on breech deliveries.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [RA], upon reasonable request.

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics (2019) ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 209: Obstetric Analgesia and Anesthesia. Obstet Gynecol 133(3):e208–e225. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003132.

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Cyna AM, Cuthbert A (2018) Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5(5):CD000331. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub4

Impey LWM et al (2017) Management of breech presentation. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 124(7):E152–E177

Parant O, Bayoumeu F (2020) Breech presentation: CNGOF guidelines for clinical practice—labour and induction. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol 48(1):136–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gofs.2019.10.022

A. C. on O (2006) Practice, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 340. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol 108(1):235–237.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of breech presentation at term. https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Management-of-breech-presentation.pdf.

Kotaska A, Menticoglou S (2019) No. 384-management of breech presentation at term. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 41(8):1193–1205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2018.12.018

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR (2000) Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet Lond. Engl. 356(9239):1375–1383. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3

Su M et al (2007) Factors associated with maternal morbidity in the term breech trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 29(4):324–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32442-2

Su M et al (2003) Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcome in the Term Breech trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189(3):740–745. https://doi.org/10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00822-6

Goffinet F et al (2006) Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am J Obstet Gynecol 194(4):1002–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.817

Macharey G et al (2017) Risk factors associated with adverse perinatal outcome in planned vaginal breech labors at term: a retrospective population-based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1):93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1278-8

Chadha YC, Mahmood TA, Dick MJ, Smith NC, Campbell DM, Templeton A (1992) Breech delivery and epidural analgesia. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 99(2):96–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14462.x

Toijonen A, Heinonen S, Gissler M, Macharey G (2021) Risk factors for adverse outcomes in vaginal preterm breech labor. Arch Gynecol Obstet 303(1):93–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05731-y

Kielland-Kaisen U et al (2020) Maternal and neonatal outcome after vaginal breech delivery of nulliparous versus multiparous women of singletons at term-A prospective evaluation of the Frankfurt breech at term cohort (FRABAT)“. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 252:583–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.029

Jennewein L et al (2018) Maternal and neonatal outcome after vaginal breech delivery at term of children weighing more or less than 3.8 kg: a FRABAT prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 13(8):e0202760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202760

Jennewein L et al (2019) The influence of the fetal leg position on the outcome in vaginally intended deliveries out of breech presentation at term: a FRABAT prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 14(12):e0225546. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225546

Möllmann CJ et al (2020) Vaginal breech delivery of pregnancy before and after the estimated due date-A prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 252:588–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.03.053

Paul B et al (2020) Maternal and neonatal outcome after vaginal breech delivery at term after cesarean section - a prospective cohort study of the Frankfurt breech at term cohort (FRABAT)“. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 252:594–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.030

Louwen F, Daviss B-A, Johnson KC, Reitter A (2017) Does breech delivery in an upright position instead of on the back improve outcomes and avoid cesareans? Int J Gynecol Obstet 136(2):151–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12033

Massey FJ (1951) The kolmogorov-smirnov test for goodness of fit. J Am Stat Assoc 46(253):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1951.10500769

McHugh ML (2013) The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem Medica 23(2):143–149. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2013.018

Mishra P, Singh U, Pandey CM, Mishra P, Pandey G (2019) Application of student’s t-test, analysis of variance, and covariance. Ann Card Anaesth 22(4):407–411. https://doi.org/10.4103/aca.ACA_94_19

Boateng EY, Abaye DA (2019) A review of the logistic regression model with emphasis on medical research. J Data Anal Inf Process. 7:4. https://doi.org/10.4236/jdaip.2019.74012

Hawkins JL et al (2010) Epidural analgesia for labor and delivery. N Engl J Med 362(16):1503–1510

Lucovnik M, Blajic I, Verdenik I, Mirkovic T, Stopar Pintaric T (2018) Impact of epidural analgesia on cesarean and operative vaginal delivery rates classified by the Ten Groups Classification System. Int J Obstet Anesth 34:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.01.003

Shmueli A et al (2018) The impact of epidural analgesia on the duration of the second stage of labor. Birth Berkeley Calif 45(4):377–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12355

Lawrence A, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Styles C (2013) Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003934.pub4

Acknowledgements

The authors are in great gratitude toward all participants and the whole team staff of the obstetrics department at Frankfurt Goethe University hospital.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA, DB, and FJR contributed to manuscript writing and editing, and data collection. NZ collected data. FL was responsible for protocol/project development. LJ performed protocol/project development, data analysis, and manuscript writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Allert, R., Brüggmann, D., Raimann, F.J. et al. The influence of epidural anesthesia in pregnancies with scheduled vaginal breech delivery at term: a hospital-based retrospective analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 310, 261–268 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-07244-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-07244-w