Abstract

Purpose

Preterm birth (PTB) can be categorised according to aetiology into: spontaneous preterm labour (SPL), preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM), and iatrogenic (iatro) PTB. Outcomes could differ between these groups, which could be of interest in counselling. We aimed to explore differences between aetiologic groups of PTB in maternal demographics, obstetrical characteristics and management, and neonatal outcomes.

Methods

This is a cohort study (2012–2018) in Ghent University Hospital, Belgium, of deliveries from 24 + 0 to 33 + 6 weeks. We compared perinatal demographics, management, and outcomes between the aetiologic types of PTB. Point and interval estimates for differences between aetiologic types were estimated using a Generalised Estimating Equations approach to handle clustering due to multiple gestations.

Results

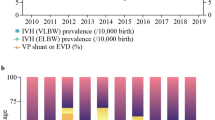

813 mothers and 987 neonates were included. Prevalences of different aetiologic types of PTB were similar. Maternal BMI was higher in the iatrogenic group (iatro-SPL: + 1.92 kg/m2, 95% CI 1.02, 2.83; iatro-PPROM: + 2.06 kg/m2, 95% CI 1.15, 2.96). There was an inversed sex ratio (0.82, 95% CI 0.65, 1.03), more growth restriction (iatro-SPL: + 22.60%, 95% CI 17.08, 28.13; iatro-PPROM: + 24.64%, 95% CI 19.44, 29.83), and a higher caesarean section rate in the iatrogenic group (iatro-SPL: + 57.23%, 95% CI 50.32, 64.13, iatro-PPROM: + 56.79%, 95% CI 50.20, 63.38) and more patients received at least one complete course of antenatal corticosteroids (iatro-SPL: + 17.60%, 95% CI 10.60, 24.60, iatro-PPROM: + 10.73%, 95% CI 4.52, 16.94). In all types of PTB, adverse neonatal outcomes had a low prevalence, except for respiratory distress syndrome. A composite of adverse neonatal outcome was more prevalent in the SPL- compared to the PPROM group, and there was less intraventricular haemorrhage in the iatrogenic group.

Conclusion

Additional to gestational age at birth, the aetiology of PTB is associated with neonatal outcome. More data are needed to enable individualised management and counselling in case of threatened PTB.

Trial registration number

NCT03405116.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

The dataset used and analysed during this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Antenatal corticosteroids

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CLD:

-

Chronic lung disease

- GEE:

-

Generalised estimating equations

- iatro:

-

Iatrogenic preterm birth

- IUGR:

-

Intra-uterine growth restriction

- IVH:

-

Intraventricular haemorrhage

- NEC:

-

Necrotising enterocolitis

- NICU:

-

Neonatal intensive care unit

- PDA:

-

Persistent ductus arteriosus

- PPROM:

-

Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes

- PTB:

-

Preterm birth

- PVL:

-

Periventricular leukomalacia

- REDCap® :

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

- RDS:

-

Respiratory distress syndrome

- ROP:

-

Retinopathy of prematurity

- SPL:

-

Spontaneous preterm labour

References

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) Preterm birth fact sheet. WHO. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth. Accessed 17 July 2018

Devlieger R, Martens E, Goemaes R, Cammu H (2018) Perinatale Activiteiten in Vlaanderen 2017. Studiecentrum Perinatale Epidemiologie (SPE). https://www.zorg-en-gezondheid.be/belangrijkste-trends-in-geboorte-en-bevalling. Accessed 17 Dec 2018

Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R (2008) Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371(9606):75–84

Frey HA, Klebanoff MA (2016) The epidemiology, etiology, and costs of preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 21(2):68–73

March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the children, WHO (2012) Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth. WHO. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/born_too_soon/en/. Accessed 17 July 2018

Purisch SE, Gyamfi-Bannerman C (2017) Epidemiology of preterm birth. Semin Perinatol 41(7):387–391

Saigal S, Doyle LW (2008) An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 371(9608):261–269

Flemish MIC/NIC services (2014) Aanbeveling perinatale zorgen rond levensvatbaarheid in Vlaanderen. Flemish MIC/NIC services. http://docplayer.nl/7966028-Aanbevelingen-perinatale-zorgen-rond-levensvatbaarheid-in-Vlaanderen.html. Accessed 17 July 2018

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap®)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381

van ʼt Hooft J, Duffy JM, Daly M, Williamson PR, Meher S, Thom E, Saade GR, Alfirevic Z, Mol BWJ, Khan KS, Global Obstetrics Network (GONet) (2016) A core outcome set for evaluation of interventions to prevent preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 127(1):49–58

Wang M (2014) Generalized estimating equations in longitudinal data analysis: a review and recent developments. Adv Stat. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/303728

Ananth C, Platt P, Savitz D (2005) Regression models for clustered binary responses: Implications of ignoring the intracluster correlation in an analysis of perinatal mortality in twin gestations. Ann Epidemiol 15(4):293–301

Yelland L, Sullivan T, Pavlou M, Seaman S (2015) Analysis of randomised trials including multiple births when birth size is informative. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 29(6):567–575

Moutquin J-M (2003) Classification and heterogeneity of preterm birth. BJOG 110(Suppl 20):30–33

Bastek J, Srinivas S, Sammel M, Elovitz M (2010) Do neonatal outcomes differ depending on the cause of preterm birth? A comparison between spontaneous birth and iatrogenic delivery for preeclampsia. Am J Perinatol 27:163–170

Morken NH, Källen K, Jacobsson B (2007) Outcomes of preterm children according to type of delivery onset: a nationwide population-based study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 21(5):458–464

Grill A, Olischar M, Weber M, Pollak A, Leitich H (2014) Type of delivery onset has a significant impact on post-natal mortality in preterm infants of less than 30 weeks’ gestation. Acta Paediatr 103(7):722–726

Delorme P, Goffinet F, Ancel PY, Foix-lʼHélias L, Langer B, Lebeaux C, Marchand LM, Zeitlin J, Ego A, Arnaud C, Vayssiere C, Lorthe E, Durrmeyer X, Sentilhes L, Subtil D, Debillon T, Winer N, Kaminski M, D’Ercole C, Dreyfus M, Carbonne B, Kayem G (2016) Cause of preterm birth as a prognostic factor for mortality. Obstet Gynecol 127(1):40–48

Garite T, Combs A, Maurel K, Das A, Huls K, Porreco R, Reisner D, Lu G, Bush M, Morris B, Bleich A, Obstetrix Collaborative Research Network (2017) A multicenter prospective study of neonatal outcomes at less than 32 weeks associated with indications for maternal admission and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217(1):72.e1–72.e9

Chevallier M, Debillon T, Pierrat V, Delorme P, Kayem G, Durox M, Goffinet F, Marret S, Ancel PY, Neurodevelopment EPIPAGE 2 Writing Group (2017) Leading causes of preterm delivery as risk factors for intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants: results of the EPIPAGE 2 cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 216(5):518.e1–518.e12

Davidian M, Louis TA (2012) Why statistics? Science 336(6077):12

Wasserstein R, Schirm A, Lazar N (2019) Moving to a world beyond “p < 0.05”. Am Stat 73(1):1–19

Stout MJ, Busam R, Macones GA, Tuuli MG (2014) Spontaneous and indicated preterm birth subtypes: interobserver agreement and accuracy of classification. Am J Obstet Gynecol 211(5):530.e1–530.e5304

Bai J, Wong F, Bauman A, Mohsin M (2002) Parity and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 186:274–278

Torloni MR, Betrán AP, Daher S, Widmer M, Dolan SM, Menon R, Bergel E, Allen T, Merialdi M (2009) Maternal BMI and preterm birth: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 22(11):957–970

Hou L, Wang X, Zou L, Chen Y, Zhang W (2014) Cross sectional study in China: fetal gender has adverse perinatal outcomes in mainland China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14:372–380

Liu Y, Li G, Zhang W (2017) Effect of fetal gender on pregnancy outcomes in Northern China. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 30(7):858–863

Khalil MM, Alzahra E (2013) Fetal gender and pregnancy outcomes in Libya: a retrospective study. Libyan J Med. https://doi.org/10.3402/ljm.v8i0.20008

Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR (2017) Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3(3):CD004454

Dehaene I, Bergman L, Turtiainen P, Ridout A, Mol BW, Lorthe E, International Spontaneous Preterm birth Young Investigators group (I-SPY) (2017) Maintaining and repeating tocolysis: a reflection on evidence. Semin Perinatol 41(8):468–476

Nijman TA, van Vliet EO, Koullali B, Mol BW, Oudijk MA (2016) Antepartum and intrapartum interventions to prevent preterm birth and its sequelae. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 21(2):121–128

Hösli I, Sperschneider C, Drack G, Zimmermann R, Surbek D, Irion O, Swiss Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2014) Tocolysis for preterm labour: expert opinion. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289(4):903–909

Chollat C, Le Doussal L, de la Villéon G, Provost D, Marret S (2017) Antenatal magnesium sulphate administration for fetal neuroprotection: a French national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1):304

Bousleiman SZ, Rice MM, Moss J, Todd A, Rincon M, Mallett G, Milluzzi C, Allard D, Dorman K, Ortiz F, Johnson F, Reed P, Tolivaisa S, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (2015) Use and attitudes of obstetricians toward 3 high-risk interventions in MFMU Network hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213(3):398.e1–398.e11

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Nathalie Filliers and Dr. Celien Van Poeck for their help with collecting the data.

Funding

The authors declare that there are no sources of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ID: project development, data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing. Major revisions. ES: data collection and management, manuscript writing. Major revisions. JS: data analysis, manuscript editing. Major revisions. KDC: Data collection and management, manuscript editing. JD: manuscript editing. KS: manuscript editing. KR: manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital on February 26th, 2018, with registration number BE670201835532.

Consent to participate

Retrospective data were obtained from 2012 till mid-2017 after opt-out consent. From mid-2017, data were collected prospectively, after obtaining informed consent of the couple. Couples were informed about the goal of the study and the destination of their data. Participation was voluntary and never influenced the care in the hospital. Couples could withdraw from the study at any time. All data were handled with professional confidentiality and anonymised for analysis.

Consent for publication

Patients gave consent regarding publishing their data.

Code availability

The software application and custom code are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dehaene, I., Scheire, E., Steen, J. et al. Obstetrical characteristics and neonatal outcome according to aetiology of preterm birth: a cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 302, 861–871 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05673-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05673-5