Abstract

Purpose

The management of cervical cancer in pregnancy persists to be challenging. Therefore, identification of factors that influence the choice of therapeutic management is pivotal for an adequate patient counseling.

Methods

We present a literature review of 26 studies reporting 121 pregnancies affected by cervical cancer. Additionally, we add a retrospective case series of five patients with pregnancy-associated cervical cancer diagnosed and treated in our clinic between 2006 and 2013.

Results

The literature review revealed that the therapeutic management during pregnancy varies according to the gestational age at diagnosis, while in the postpartum period no influence on the treatment choice could be detected. Also in our case series the choice of oncologic therapy was influenced by the gestational age, the wish to continue the pregnancy and the risks of delaying definitive treatment.

Conclusions

There are no standardized procedures concerning the treatment of cervical cancer in pregnancy. Therefore, in consultation with the patient and a multidisciplinary team, an adequate individualized treatment plan should be determined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC), comprising both squamous and glandular differentiation, is not only the fourth most frequent malignancy but also the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide. Among the malignant tumors of the cervix, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common subtype and therefore characterizes the clinical and epidemiological picture of the disease. Although the tumor is virtually preventable by human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and effective screening strategies, its peak occurrence coincides with the prime reproductive years in non-compliant populations [1]. Accordingly, CC is one of the three most common pregnancy-associated cancer types with a crude incidence rate of 4 per 100,000 pregnancies [2]. Different data suggest that a diagnosis in pregnancy does not affect survival rates negatively [3]. However, these observations should be handled with care due to limited literature. The treatment of CC in pregnancy is complex. It has to take into consideration the optimal oncologic therapy as well as the preservation of the health of the fetus. Treatment options include conservative and surgical approaches based on tumor size, lymph node involvement, gestational age (GA) and the patient’s wish to continue the pregnancy [4]. To help provide a basis for treatment decisions, we here report our clinical management of five women diagnosed and treated with SCC during pregnancy. Additionally, we present a literature review focused on treatment options of gestational CC. We hypothesized that the GA at diagnosis might influence the choice of treatment and aimed to evaluate whether this might affect maternal outcome.

Materials and methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical files of 84 pregnant women out of a total of approximately 2800 patients who presented at the outpatient department for genital dysplasia of Bonn University between 2006 and 2013. Patients were retrieved from the pathological database (PathoPro software, Institute for Medical Software, Saarbrücken, Germany) using the following search terms: ‘pregnancy’, ‘weeks of gestation’, ‘cervical dysplasia’ and ‘abnormal Pap smear’. Out of the cohort, five (5.95 %) patients with SCC were identified and included in this case series. Clinical information was gained from medical records; developmental charts were used to assess health outcome of newborns; follow-up data were updated until October 2015. In all women, colposcopy was performed using the photo and video colposcope 3MV (Leisegang, Berlin, Germany); image processing was carried out using the 3MV-Videology Viewer software 3.8.5.6 (Leisegang); application of 3 % acetic acid allowed the identification of cervical epithelial changes. Additionally, in all patients, colposcopy-directed biopsies of suspicious lesions were undertaken. Pap tests were evaluated according to the Munich nomenclature II; World Health Organization (WHO) criteria were used for histopathological diagnosis; tumor grade was determined based on the modified Broders’ classification [5]; tumors were staged clinically according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system [6]; the lymph node status was recorded separately.

Literature search

A systematic computerized search was performed using PubMed and Web of Science (1995-2014) with the language being restricted to English. The PubMed query was conducted by combining the following MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms: ‘pregnancy complications/neoplastic/therapy’, ‘uterine cervical neoplasms’ and ‘carcinoma/squamous cell’; the MeSH keyword ‘trachelectomy’ was excluded. A similar strategy was applied to the Web of Science database using the following query: Title (TI) = (cervical cancer) AND TI = (pregnancy) AND Research Area (SU) = (Oncology) AND TS = (therapy) AND TS = (squamous) NOT Topic (TS) = (trachelectomy). Abstracts were explored for relevant information; full-text articles were used for further details. Authors were contacted if the complete manuscript could not be retrieved otherwise. Publications to be reviewed were selected by TH and KK. Case reports and retrospective trials were included; unpublished data were not accepted.

Thirty-seven studies met inclusion criteria. Three publications were excluded since they provided a review only [7–9]; two publications were excluded since they analyzed preneoplastic lesions [10, 11]; three publications were excluded since they did not provide original data to each patient [12–14]; two publications were excluded since we were unable to retrieve the whole publication [15, 16]; one publication was excluded since a successful pregnancy after the treatment of CC was reported [17]; 26 studies reporting 121 pregnancies [18–43] were used for the systematic review. The following data points were collected: baseline characteristics (age at diagnosis, GA at diagnosis), tumor characteristics (FIGO stage, histopathology), therapy (during pregnancy, in the postpartum period), obstetric characteristics (obstetric history, mode and GA of delivery, neonatal outcome) and maternal outcome. Our aim was to identify typical pattern and trends according to the GA at diagnosis. Therefore, patients were divided by their time point of tumor detection in early (<20 weeks (wks) GA) and late-diagnosed (≥20 wks GA) disease.

Statistical analysis

The F test was used to analyze the assumption of equal variances; the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare differences in the following groups: age at diagnosis, GA at delivery and follow-up. For categorical variables the Chi-square test was used to investigate statistical significance of differences: FIGO stage, histopathology, therapy during pregnancy, therapy in the postpartum period, mode of delivery and status of maternal outcome. Additionally, Yates correction was performed. Results with a p value of <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Case series

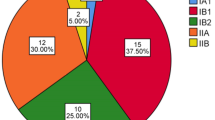

Five cases of SCC in pregnancy were identified during the study period. Median age at diagnosis was 32 years (range 30–37; Table 1). Risk factors included tobacco use and high-risk HPV positivity. Three patients did not participate in the screening program; two women had abnormal Pap smear results before getting pregnant. All patients were referred to a colposcopic examination during pregnancy. Diagnosis of SCC was made by biopsy in four pregnant women; in one patient, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) III was detected in gravidity. However, in the postpartum period, the conization tissue showed malignant cells suggesting progression of the disease. Four biopsies were performed in the second and one in the third trimenon for the diagnosis of cancer. All Pap smears were without evidence of malignancy. All patients of our case series were diagnosed with early staged SCC (Table 2). Poor prognostic factors included the presence of lymph node metastasis in one patient, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) in two and low differentiation in three women.

Of all patients diagnosed with SCC in the second trimenon, one woman decided to terminate pregnancy (case 4). Radical hysterectomy with the fetus in situ and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection was performed at the GA of 19 wks. Another woman was treated by conization at 21 wks of gestation (case 1). In this case, early staged SCC with negative margins for invasive disease was diagnosed. Pregnancy was prolonged, regular colposcopic controls were undertaken, and a cesarean delivery (CD) plus hysterectomy was performed at 35 wks of gestation. The final pathologic examination showed residual CIN but no invasive disease. The tumor of the third patient diagnosed in the second trimenon (20 wks GA) was 3 cm in diameter and exhibited LVI (case 5) [44]. Since this patient wished to continue her pregnancy, four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin were administered. Clinical and colposcopic follow-ups were scheduled every 3 weeks confirming stable disease (Fig. 1a). An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan at 20 wks of gestation was performed using a 1.5-T system (Intera, Philips Medical Systems, Best, Netherlands) to rule out lymph node involvement and advanced disease (Fig. 1b). Staging laparoscopy was refused by the patient. The fetal well-being was monitored regularly with ultrasonography and Doppler scan and showed no signs of intrauterine growth restriction. The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without any significant side effects. After reaching fetal pulmonary maturity, CD and radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy were performed at 35 wks of gestation. To assess the effect of chemotherapy on cell proliferation, 2–3 µm formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were stained with the mouse antihuman Ki-67 IgG1 monoclonal antibody (clone MIB-1, dilution 1:500; Dako, Hamburg, Germany) using an automated staining system (Medac 480 S Autostainer; Medac, Wedel, Germany), HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and the DAB system (Medac). The pathologic examination revealed a Ki-67 activity of 36.47 % after neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to a proliferation index of 32.22 % at initial diagnosis suggesting stable disease (Fig. 1c). In the postpartum period, the patient received adjuvant treatment consisting of cisplatin-based radiochemotherapy.

An example of the individual management of cervical cancer FIGO stage IB1 in pregnancy (case 5, after [44]). a Colposcopy in pregnancy was performed at initial diagnosis and subsequently during neoadjuvant chemotherapy to monitor the response to treatment; acetic acid was used for the visualization of cervical changes. Signs of invasive disease included atypical vessels and ulceration (arrow). b A pelvic MRI scan was performed at 20 wks GA and ruled out lymph node involvement; the sagittal T2-weighted image identifies the tumor by an increase in size and signal intensity (arrow). c Representative images of Ki-67 expression in non-treated and treated SCC visualized by immunohistochemistry (brown, arrow); hematoxylin (blue) was used for nuclear staining (bright field image, ×100 magnification)

In one patient, SCC was diagnosed in the early third trimenon (case 2). Due to a history of abnormal Pap smears over the past 5 years, she was referred to our colposcopic unit in early pregnancy. Cytologic results were normal, and accordingly, no colposcopy-directed biopsy was taken. However, the colposcopy in 32 wks of gestation showed a suspect area. Consequently, a biopsy was done revealing high-grade CIN with focal micro-invasive SCC. CD was performed at 36 wks of gestation; a conization was undertaken in the postpartum period.

In one case, SCC was diagnosed in the postpartum period (case 3). The patient was referred to our clinic 8 wks after delivery, and a conization was performed diagnosing invasive disease. Radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection was undertaken. Additionally, the patient received adjuvant treatment consisting of cisplatin-based radiochemotherapy and brachytherapy.

With regard to the obstetrical history, the median gestational age at delivery was 35.5 wks (range 35–40; Table 3). All children were born with average birth weights for their GA. No significant complications at birth and neonatal course were noted. No long-term complications were detected. In particular, the child whose mother received platinum-based chemotherapy during pregnancy showed a normal development. As of today, all patients (Table 1) and their children (Table 3) undergo regular checkups and are healthy and alive.

Review of the literature

Details for each case of the literature review are given in Supplementary Table S1. Tumors were classified according to their GA at detection in early and late-diagnosed disease, and variables were compared (Table 4). No difference was found between groups regarding patient and tumor characteristics as well as maternal outcome. We identified a significant discrepancy in the oncological management during pregnancy but not after delivery between early- and late-diagnosed tumors. Accordingly, the GA and the mode of delivery differed in both groups.

Discussion

Although its incidence rate has been declining in the last years, CC is one of the most frequently diagnosed malignancies in pregnancy. Due to an increase in women choosing to become pregnant later in their lives, even a further rise of gestational CC is plausible [2]. Literature on the clinical management of CC in pregnancy is scarce. Therefore, we retrospectively analyzed pregnancy-associated CC cases in our clinic and performed a literature review that focused on treatment approaches.

We found therapeutic modalities in pregnancy still to be limited consisting mainly of conization and chemotherapy. Alternatively, tumors can either be followed up or pregnancy can be interrupted for definitive therapy according to guidelines [45]. Treatment decisions in pregnancy depended on the GA at first diagnosis. Accordingly, women obtained interruptions until 20 wks after conception more often as women who are more than 20-wk pregnant. In the latter case, the concept of ‘watchful waiting’ appeared to be typical. According to these results, also the mode and the GA at delivery correlated with the time point of first diagnosis in pregnancy. However, different treatment approaches across all gestational ages appeared not to affect negatively the mother’s survival. Taken together, our literature review underlines the therapeutic complexity of CC in pregnant women since decisions have to take into account the impact upon mother and fetus. Consistent with this observation, different treatment approaches were also seen in our case series of pregnancy-associated SCC.

An overview of treatment options according to the clinical stage is given in Fig. 2 modified after Hunter et al. [46, 47]. Prolongation of the pregnancy at an early stage and thus delaying definite treatment were reported to be safe [3]. Diagnostic conization, though associated with a significant risk of hemorrhage, might help to assess the actual invasion depth after biopsy showing micro-invasive disease [4]. Lymph node involvement can be assessed by MRI scans, thereby providing the basis for prolonging pregnancy [22]. Alternatively, laparoscopic lymphadenectomy has emerged as an effective and more precise procedure during pregnancy [48]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy during gestation might be possible in selected patient groups, defined by advanced disease or high-risk carcinomas, allowing for fetal maturation. However, the choice has to be individually made, weighing the risk of antenatal toxicity against the delay of curative treatment. Platinum was shown to be a safe option during pregnancy [49], especially since platinum concentrations are extremely low in the fetal unit suggesting placental filtration [50]. The timing of delivery is a critical point in the management of gestation-associated CC. In accordance with current guidelines, preterm labor was tolerated in our cohort to compromise between fetal maturity and completion of the mothers’ oncological treatment [51].

Undoubtedly, the most successful strategy against CC in pregnancy is the participation in preconceptive cancer screening programs. Most of the patients in our cohort did not undergo regular gynecological examinations before getting pregnant. Since the Pap smear is an essential part of early antenatal care, it allows detecting cervical changes also in the under-screened population and has the advantage to detect a tumor at an early stage. Accordingly, all CCs in the non-screened patients of our case series were diagnosed at FIGO stage I, which is in accordance with published data [52]. Only two patients of our cohort participated regularly in the screening program. They were diagnosed with suspect Pap smears before getting pregnant and referred for colposcopy only after the onset of pregnancy. Their subsequent diagnosis of malignancy underlines the importance of the histopathological evaluation in the case of repeated abnormal cytological results. Especially during pregnancy, colposcopy-directed biopsies should be preferred since hormone-related cellular changes may be misidentified in Pap smears [53]. Colposcopy-directed biopsy is a safe and reliable procedure during pregnancy. Delayed bleeding can occur but is often successfully resolved with the application of pressure [54].

Taken together, women with suspect Pap test desiring to bear a child should postpone their pregnancy until definite treatment of dysplasia took place. Pregnant women with suspect Pap smears should be referred to a colposcopic unit where experienced colposcopists are familiar with the physiological changes of the uterine cervix during pregnancy. Being diagnosed with CC during pregnancy, management depends on different factors including the stage of disease, the week of gestation and the woman’s desire to bear a child. Thus, an individualized treatment plan for each patient is required.

References

Gustafsson L, Ponten J, Bergstrom R, Adami HO (1997) International incidence rates of invasive cervical cancer before cytological screening. Int J Cancer 71(2):159–165

Eibye S, Kjaer SK, Mellemkjaer L (2013) Incidence of pregnancy-associated cancer in Denmark, 1977–2006. Obstet Gynecol 122(3):608–617. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a057a2

Germann N, Haie-Meder C, Morice P, Lhomme C, Duvillard P, Hacene K, Gerbaulet A (2005) Management and clinical outcomes of pregnant patients with invasive cervical cancer. Ann Oncol 16(3):397–402. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi084

Van Calsteren K, Vergote I, Amant F (2005) Cervical neoplasia during pregnancy: diagnosis, management and prognosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 19(4):611–630. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.03.002

Broders AC (1922) Epithelioma of the genito-urinary organs. Ann Surg 75(5):574–604

Pecorelli S (2009) Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105(2):103–104

Goncalves CV, Duarte G, Costa JS, Marcolin AC, Bianchi MS, Dias D, Lima LC (2009) Diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer during pregnancy. Sao Paulo Med J 127(6):359–365

Method MW, Brost BC (1999) Management of cervical cancer in pregnancy. Semin Surg Oncol 16(3):251–260

Sood AK, Sorosky JI (1998) Invasive cervical cancer complicating pregnancy. How to manage the dilemma. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 25(2):343–352

Robova H, Rob L, Pluta M, Kacirek J, Halaska M Jr, Strnad P, Schlegerova D (2005) Squamous intraepithelial lesion-microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix during pregnancy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 26(6):611–614

Harper DM, Roach MS (1996) Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in pregnancy. J Fam Pract 42(1):79–83

Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Krogman S, Anderson B, Benda J, Buller RE (1996) Surgical management of cervical cancer complicating pregnancy: a case-control study. Gynecol Oncol 63(3):294–298. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0325

Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Mayr N, Krogman S, Anderson B, Buller RE, Hussey DH (1997) Radiotherapeutic management of cervical carcinoma that complicates pregnancy. Cancer 80(6):1073–1078

Sood AK, Sorosky JI, Mayr N, Anderson B, Buller RE, Niebyl J (2000) Cervical cancer diagnosed shortly after pregnancy: prognostic variables and delivery routes. Obstet Gynecol 95(6 Pt 1):832–838

Lal S, Kriplani A, Bhatla N, Agarwal N (2011) Invasive carcinoma of cervix during pregnancy—a case report and review of literature. J Indian Med Assoc 109(10):751–752

McDonald SD, Faught W, Gruslin A (2002) Cervical cancer during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 24(6):491–498

Kobayashi Y, Akiyama F, Hasumi K (2006) A case of successful pregnancy after treatment of invasive cervical cancer with systemic chemotherapy and conization. Gynecol Oncol 100(1):213–215. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.08.018

Sorosky JI, Squatrito R, Ndubisi BU, Anderson B, Podczaski ES, Mayr N, Buller RE (1995) Stage I squamous cell cervical carcinoma in pregnancy: planned delay in therapy awaiting fetal maturity. Gynecol Oncol 59(2):207–210. doi:10.1006/gyno.1995.0009

Allen DG, Planner RS, Tang PT, Scurry JP, Weerasiri T (1995) Invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 35(4):408–412

Tewari K, Cappuccini F, Balderston KD, Rose GS, Porto M, Berman ML (1998) Pregnancy in a Jehovah’s witness with cervical cancer and anemia. Gynecol Oncol 71(2):330–332. doi:10.1006/gyno.1998.5187

Tewari K, Cappuccini F, Gambino A, Kohler MF, Pecorelli S, DiSaia PJ (1998) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced cervical carcinoma in pregnancy: a report of two cases and review of issues specific to the management of cervical carcinoma in pregnancy including planned delay of therapy. Cancer 82(8):1529–1534

van Vliet W, van Loon AJ, ten Hoor KA, Boonstra H (1998) Cervical carcinoma during pregnancy: outcome of planned delay in treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 79(2):153–157

Marana HR, de Andrade JM, da Silva Mathes AC, Duarte G, da Cunha SP, Bighetti S (2001) Chemotherapy in the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer and pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol 80(2):272–274. doi:10.1006/gyno.2000.6055

Takushi M, Moromizato H, Sakumoto K, Kanazawa K (2002) Management of invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix associated with pregnancy: outcome of intentional delay in treatment. Gynecol Oncol 87(2):185–189

Ostrom K, Ben-Arie A, Edwards C, Gregg A, Chiu JK, Kaplan AL (2003) Uterine evacuation with misoprostol during radiotherapy for cervical cancer in pregnancy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 13(3):340–343

Hogg R, Ungar L, Hazslinszky P (2005) Radical hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma in pregnant women–a case of decidua mimicking metastatic carcinoma in pelvic lymph nodes. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 26(5):499–500

Bader AA, Petru E, Winter R (2007) Long-term follow-up after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk cervical cancer during pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol 105(1):269–272. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.009

Traen K, Svane D, Kryger-Baggesen N, Bertelsen K, Mogensen O (2006) Stage Ib cervical cancer during pregnancy: planned delay in treatment–case report. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 27(6):615–617

Palaia I, Pernice M, Graziano M, Bellati F, Panici PB (2007) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radical surgery in locally advanced cervical cancer during pregnancy: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197(4):e5–e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.034

Karam A, Feldman N, Holschneider CH (2007) Neoadjuvant cisplatin and radical cesarean hysterectomy for cervical cancer in pregnancy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4(6):375–380. doi:10.1038/ncponc0821

Benhaim Y, Pautier P, Bensaid C, Lhomme C, Haie-Meder C, Morice P (2008) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced stage cervical cancer in a pregnant patient: report of one case with rapid tumor progression. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 136(2):267–268. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.10.027

Gonzalez Bosquet E, Castillo A, Medina M, Sunol M, Capdevila A, Lailla JM (2008) Stage 1B cervical cancer in a pregnant woman at 25 weeks of gestation. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 29(3):276–279

Marnitz S, Kohler C, Oppelt P, Schmittel A, Favero G, Hasenbein K, Schneider A, Markman M (2010) Cisplatin application in pregnancy: first in vivo analysis of 7 patients. Oncology 79(1–2):72–77. doi:10.1159/000320156

Herod JJ, Decruze SB, Patel RD (2010) A report of two cases of the management of cervical cancer in pregnancy by cone biopsy and laparoscopic pelvic node dissection. BJOG 117(12):1558–1561. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02723.x

Rabaiotti E, Sigismondi C, Montoli S, Mangili G, Candiani M, Vigano R (2010) Management of locally advanced cervical cancer in pregnancy: a case report. Tumori 96(4):623–626

Chun KC, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH (2010) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum followed by radical surgery in early cervical cancer during pregnancy: three case reports. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40(7):694–698. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyq039

Hafeez I, Lawenda BD, Schilder JM, Johnstone PA (2011) Prolonged survival after episiotomy recurrence of cervical cancer complicating pregnancy. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 32(2):211–213

Li J, Wang LJ, Zhang BZ, Peng YP, Lin ZQ (2011) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus platinum for invasive cervical cancer in pregnancy: two case report and literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet 284(3):779–783. doi:10.1007/s00404-011-1943-5

Hidaka T, Nakashima A, Hasegawa T, Nomoto K, Ishizawa S, Tsuneyama K, Takano Y, Saito S (2011) Ovarian squamous cell carcinoma which metastasized 8 years after cervical conization for early microinvasive cervical cancer: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41(6):807–810. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyr041

Guzel AI, Ozgu E, Akbay S, Erkaya S, Gungor T (2013) Report of a pregnant woman underwent radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. J Exp Ther Oncol 10(3):235–236

Geijteman EC, Wensveen CW, Duvekot JJ, van Zuylen L (2014) A child with severe hearing loss associated with maternal cisplatin treatment during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 124(2 Pt 2 Suppl 1):454–456. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000389

Caluwaerts S, Van Calsteren K, Mertens L, Lagae L, Moerman P, Hanssens M, Wuyts K, Vergote I, Amant F (2006) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical hysterectomy for invasive cervical cancer diagnosed during pregnancy: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16(2):905–908. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00223.x

Favero G, Chiantera V, Oleszczuk A, Gallotta V, Hertel H, Herrmann J, Marnitz S, Kohler C, Schneider A (2010) Invasive cervical cancer during pregnancy: laparoscopic nodal evaluation before oncologic treatment delay. Gynecol Oncol 118(2):123–127. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.04.012

Hecking T, Kübler K (2015) Abnormal cervical cytology in pregnancy. Der Gynäkologe. doi:10.1007/s00129-015-3801-1 (first online: 30 October 2015)

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie: Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der Patientin mit Zervixkarzinom, Langversion, 1.0, 2014, AWMF-Registernummer: 032/033OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html, [Stand 15. September 2014]

Hunter MI, Tewari K, Monk BJ (2008) Cervical neoplasia in pregnancy. Part 2: current treatment of invasive disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199(1):10–18. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.011

Kuhn W, Possinger K, Willich N (2012) Gynäkologische Malignome—Tumortherapie und Nachsorge bei Mamma- und Genitalmalignomen. 10th edn. W. Zuckerschwerdt Verlag München

Vercellino GF, Koehler C, Erdemoglu E, Mangler M, Lanowska M, Malak AH, Schneider A, Chiantera V (2014) Laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy in 32 pregnant patients with cervical cancer: rationale, description of the technique, and outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24(2):364–371. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000064

Zagouri F, Sergentanis TN, Chrysikos D, Bartsch R (2013) Platinum derivatives during pregnancy in cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 121(2 Pt 1):337–343

Kohler C, Oppelt P, Favero G, Morgenstern B, Runnebaum I, Tsunoda A, Schmittel A, Schneider A, Mueller M, Marnitz S (2015) How much platinum passes the placental barrier? Analysis of platinum applications in 21 patients with cervical cancer during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.022

Amant F, Van Calsteren K, Halaska MJ, Beijnen J, Lagae L, Hanssens M, Heyns L, Lannoo L, Ottevanger NP, Vanden Bogaert W, Ungar L, Vergote I, du Bois A (2009) Gynecologic cancers in pregnancy: guidelines of an international consensus meeting. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19(Suppl 1):S1–S12. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a1d0ec

Morice P, Uzan C, Gouy S, Verschraegen C, Haie-Meder C (2012) Gynaecological cancers in pregnancy. Lancet 379(9815):558–569. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60829-5

Baldauf JJ, Dreyfus M, Ritter J, Philippe E (1995) Colposcopy and directed biopsy reliability during pregnancy: a cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 62(1):31–36

Economos K, Perez Veridiano N, Delke I, Collado ML, Tancer ML (1993) Abnormal cervical cytology in pregnancy: a 17-year experience. Obstet Gynecol 81(6):915–918

Author contributions

T. Hecking was involved in data collection and interpretation, manuscript drafting and prewriting; A. Abramian and M.D. Keyver-Paik performed clinical procedures; C. Domröse was involved in colposcopic evaluation; T. Engeln was involved in data collection; T. Thiesler was involved in immunohistochemical analysis; C. Leutner was involved in radiological examination; U. Gembruch was involved in sonographic examination; W. Kuhn revised the manuscript; K. Kübler was involved in project development and data interpretation and wrote the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hecking, T., Abramian, A., Domröse, C. et al. Individual management of cervical cancer in pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293, 931–939 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3980-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3980-y