Abstract

The population of older people is steadily increasing and the majority live at home. Although the home and community are the largest care settings worldwide, most of the evidence on dermatological care relates to secondary and tertiary care. The overall aims were to map the available evidence regarding the epidemiology and burden of the most frequent skin conditions and regarding effects of screening, risk assessment, diagnosis, prevention and treatment of the most frequent skin conditions in older people living in the community. A scoping review was conducted. MEDLINE, Embase and Epistemonikos were systematically searched for clinical practice guidelines, reviews and primary studies, as well as Grey Matters and EASY for grey literature published between January 2010 and March 2023. Records were screened and data of included studies extracted by two reviewers, independently. Results were summarised descriptively. In total, 97 publications were included. The vast majority described prevalence or incidence estimates. Ranges of age groups varied widely and unclear reporting was frequent. Sun-exposure and age-related skin conditions such as actinic keratoses, xerosis cutis, neoplasms and inflammatory diseases were the most frequent dermatoses identified, although melanoma and/or non-melanoma skin cancer were the skin conditions investigated most frequently. Evidence regarding the burden of skin conditions included self-reported skin symptoms and concerns, mortality, burden on the health system, and impact on quality of life. A minority of articles reported effects of screening, risk assessment, diagnosis, prevention and treatment, mainly regarding skin cancer. A high number of skin conditions and diseases affect older people living at home and in the community but evidence about the burden and effective prevention and treatment strategies is weak. Best practices of how to improve dermatological care in older people remain to be determined and there is a particular need for interventional studies to support and to improve skin health at home.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The world´s population is ageing. By 2050, it is anticipated that approximately 16% of the global population will be aged 65 years and older [1]. This demographic shift highlights the increased demand for effective and sustainable healthcare and long-term care services.

The majority of older people live in the community [2]. Accordingly, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasises the need to establish structures and processes that enable individuals to live and to receive care at home for as long as possible. In 2015, the WHO introduced a public health framework aiming at promoting ‘healthy ageing’ [3]. Development and maintenance of ‘functional ability’ is a central concept and the approach aims to delay, or partially reverse age-related processes that lead to functional decline and increased dependency [4].

Skin ageing is influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors including genetic predisposition, nutrition, sun damage, environmental conditions, and personal habits such as smoking [3, 5]. Age-related skin changes include thinning of the epidermis, flattening of the dermal-epidermal junction, and loss of subcutaneous fat, collagen, and elastin in the dermis. Functionally, a reduction of the skin’s viscoelastic properties and a reduced capacity for barrier function and repair following insult is observed [6, 7]. These alterations increase the susceptibility to a wide range of age-related skin problems such as xerosis cutis, pruritus, shear-type injuries, bullae formation and colonisation by pathogenic bacteria. Age-related skin conditions may have a negative impact on the quality of life and mental health of the individual, thus leading to an overall deterioration in health [6].

Chronic systemic conditions in older people including cardiovascular and renal diseases, diabetes mellitus (DM) and concomitant medications such as diuretics also affect the skin [8,9,10]. For example, patients with DM are at risk of fungal and bacterial infections, as well as foot ulceration [11]. Age-related reduced mobility, incontinence, and malnutrition contribute to a variety of skin diseases such as incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) [12] and pressure ulceration [10]. Thus, the increased risk of skin problems in older people results from a combination of various direct and indirect factors, pathways, and interactions [13].

Since 2017, the WHO provides evidence-based guidelines for detecting and managing declines in physical and mental capacities in older people, with a focus on healthcare providers in the community and primary healthcare settings [4]. While there is a substantial body of evidence supporting preventative and therapeutic strategies for skin health in secondary or tertiary care settings, a summary of empirical evidence in the community and primary care settings is missing.

This scoping review aims to examine the extent and nature of available evidence regarding skin diseases in the primary care setting. The following questions will be answered:

-

(1)

What are the most frequent skin conditions in older people living in the community?

-

(2)

What is the burden of skin conditions in older people in the community setting?

-

(3)

What type of evidence exists regarding the effects of screening, risk assessment, diagnosis, prevention and treatment of the most frequent skin conditions in older people living in the community?

Methods

Protocol and registration

A scoping review was conducted guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews [14] and a detailed review protocol was published before [13].

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used: studies conducted in community or primary care settings; participants being 60 years or older living at home; reporting of numerators/denominators/time period; descriptive and interventional study designs; systematic reviews; clinical practice guidelines; and publication from January 2010 onwards. The lower age limit of 60 years was adhered to by including only those studies in which this age limit was the inclusion criterion or in which data for this age limit could be clearly extracted. The following exclusion criteria were applied: hospital; long-term care; secondary; tertiary care settings; opinion papers; editorials; and case reports. No language restrictions were applied.

The original eligibility criteria outlined in the published protocol [13] included systematic and scoping reviews and clinical practice guidelines only and people 65 years and older (search strategy 1). These original eligibility criteria resulted in one reference only (Fig. 1). Therefore, the inclusion criteria were expanded to include people 60 years and older and various other study designs reporting empirical data (see above).

Information sources

MEDLINE and Embase were searched via OvidSP, as well as Epistemonikos. Grey Matters [15, 16] and EASY datasets by DANS [17] were searched for grey literature. EASY was used instead of OpenGrey as it was archived with DANS [18]. Reference lists and experts in the field were consulted regarding relevant additional literature.

Search

The second search strategy was conducted on 7 March 2023. Table 1 shows the search terms in MEDLINE and Embase via OvidSP. The same strategy was used for Epistemonikos. EASY and Grey Matters were searched using the terms ‘skin’, ‘community’ and ‘elderly’ as well as ‘older people’.

Selection of sources of evidence

Results of the searches were exported into EndNote. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (AF, DL) following the suggested method by Bramer, Milic and Mast [19]. Subsequently relevant results were exported to the free online software Rayyan, full-texts obtained and compared with the inclusion and exclusion criteria by both reviewers independently. Any discrepancies were discussed with a third reviewer (JK) if needed.

Data charting process, data items and synthesis of results

AF and DL split the included records, extracted data using standardised extraction sheets and checked 80% of each other’s extractions for accuracy. In the case of discrepancies, JK was consulted. For each of the three review questions tables were developed to summarise characteristics and key results. Summarized results of the included reviews were extracted directly without referring to the underlying primary studies. No studies were included twice. Only the most recent estimates were extracted from cohort studies. A critical appraisal of the sources of evidence was not conducted.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

The first search strategy yielded 3,455 citations. Of these 2,277 were screened, 15 assessed for eligibility, and finally one systematic review [20] included (Fig. 1). To increase the sensitivity the second search identified 5,461 potential records. After duplicates were removed, 3,484 citations were screened and 196 records sought for retrieval. One record could not be retrieved [21] and 113 were excluded. Most citations were excluded due to results not being presented for people ≥ 60 years or not separately for settings (n = 57), and data not being relevant (n = 46). Tables S1 and S2 (Supplementary material 1) list all excluded references with exclusion reasons from both searches. Additionally, 19 records were identified via experts and hand searching. Altogether, 97 records were included (Fig. 1). In total, 52 potential citations of grey literature were screened, of these 14 records were checked for eligibility. None met the inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

A detailed description of all 97 included publications can be found in Supplementary material 2. Table 2 presents the main characteristics: 84 publications were full-text articles and 13 were abstracts. Two abstracts referred to the same study [22, 23] and one abstract [24] referred to an included full-text article [25] indicating that in total 95 studies were included. Most studies were published after 2014 and in Europe (n = 40). The majority reported descriptive data. Multiple studies used data of the Rotterdam [26,27,28] and AugUR studies [29,30,31] for cross-sectional analyses. More than 50% of studies were based on registry or secondary data analyses and the reported ranges of age groups varied widely. A number of studies did not define ‘skin cancer’ [32,33,34,35,36].

The majority of included articles (79 articles, 77 studies) described prevalence and/or incidence estimates (review question 1), 30 studies presented evidence regarding the burden of skin conditions including self-reported symptoms or quality of life (review question 2) and 14 studies reported effects of interventions (review question 3). Table S3 (Supplementary material 3) lists all included publications with their assigned review questions, study type, and geographic region.

Results of individual sources of evidence

Table S4 (Supplementary material 4) describes the epidemiological evidence addressing review question 1. Table S5 (Supplementary material 4) summarises the scope of skin condition(s) addressed. Nine studies reported any skin condition in the sample [20, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Eight studies investigated a selection of skin conditions/diseases [33, 34, 45,46,47,48,49,50] and 60 studies focused on a specific skin condition/disease or disease group (e.g. ‘eczema’) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101].

The most often investigated skin condition was melanoma and/or non-melanoma skin cancer (n = 34) [22, 23, 26, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 69, 71, 73, 75,76,77,78,79,80, 82,83,84, 86, 89, 93, 94, 97, 101], three studies did not specify ‘skin cancer’ [32,33,34]. Different types of ‘eczema’ (including atopic dermatitis) were included in eight studies [30, 31, 33, 34, 46, 65, 88, 91], pressure injuries [45, 68, 81, 85, 90, 99] and psoriasis [29, 33, 34, 57, 58, 100] each in six studies, and xerosis/ichthyosis in five studies [24, 25, 27, 45, 47, 95]. Other studies focused on vitiligo [33, 34, 47, 62] and parasites [33, 34, 47, 92], bullous pemphigoid [59, 87, 98], intertrigo [67, 74], herpes zoster [46, 70], seborrheic dermatitis [28], granuloma annulare [72], and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections [96].

Table S6 (Supplementary material 5) presents details of included studies regarding review question 2. Most studies (n = 10) described self-reported skin concerns/complaints or symptoms such as pruritus [20, 34, 40, 42, 45, 65, 102,103,104,105]. Nine studies reported mortality [53, 63, 64, 71, 77, 79, 97, 98, 106] and seven studies dermatology-related medical visits [37, 42, 43, 107,108,109] or hospital admissions [110]. One report described depressive disorders in individuals with and without ‘skin conditions’ [111], one a potential association between ‘skin problems’ and quality of life [103] and another the perception of whether skin conditions were bothersome [104]. Two studies each reported disability adjusted life years (DALY’s) [106, 112] and complications due to herpes zoster [70, 113].

Table S7 (Supplementary material 5) describes details of the 14 articles answering review question 3. Four studies applied interventional designs [38, 68, 99, 114]. Most articles (n = 7) focused on interventions regarding ‘skin cancer’ (melanoma, melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer, not specified), four on the prevention (sun protection, awareness/education campaigns) [35, 36, 64, 115], two on screening [48, 60] and one referred to both [77]. Two articles looked into the prevention of pressure injuries, one investigating different pads in incontinent persons [99], and one introduced a pressure injury prevention protocol, including screening and risk assessment [68]. Further, two articles focused on herpes zoster, one tested a skin prick test for predicting the development of herpes zoster [114] and one the effectiveness of the vaccine in the UK [116]. One study reported on a teledermatology project in a major city in Brazil [38]. Another study sent trained community health workers to screen older people in a city in India for eczema. Suspected cases were then referred to a dermatologist [65]. Finally, one study investigated the most common types of treatments for actinic keratoses [61].

Synthesis of results

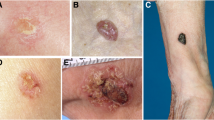

Table 3 summarises the most frequent skin conditions (prevalence 5% or higher) identified. These include skin conditions typically related to sun-exposure and age such as androgenetic alopecia, actinic keratoses and xerosis cutis, as well as neoplasms and inflammatory diseases.

Reports about burden included self-reported skin symptoms and concerns, quality of life, mortality, service use such as physician consultations (Table S6, Supplementary material 5). Pruritus was self-reported by up to 40.6% [20, 34, 40, 42, 45, 102, 104, 105, 117] (100% in individuals with eczema [65]). 15% [108] to 31.9% [43] of participants visited their General Practitioner because of their skin condition. One study reported 43% of skin conditions identified needed further care by a physician, 33% could be self-managed, and 24% needed no further treatment [37].

Most evidence in relation to the effects of screening, risk assessment and diagnosis, prevention and treatment of skin conditions had a descriptive design and analysed incidence and/or prevalence estimates in relation to prevention of and screening for ‘skin cancer’ (Table S7, Supplementary material 5). Two studies [68, 99] focusing on pressure injury prevention reported a reduction in pressure injury prevalence and/or incidence. One study describing a teledermatology project reported that 49.8% of patients were repatriated to their primary care physician and the most common prescriptions were ‘emollients’, ‘topical antifungal’, ‘sunscreen’ and ‘topical corticosteroids’ [38].

Discussion

One of the main findings of this scoping review was the unexpectedly low number of studies presenting empirical evidence about the epidemiology, burden and treatment effectiveness in skin conditions and diseases of people living at home and in the community. Furthermore, most of the evidence includes prevalence and incidence estimates and very little is reported about intervention effects. Only 4 out of 95 reports used an interventional study design. These findings highlight a substantial research gap as the vast majority of older people receives community care in their own homes. As because the community is the largest care setting globally, it is of utmost importance to improve community care [4], including skin and dermatological care.

Regardless, this scoping review suggests that the most prevalent skin conditions and diseases in older community-living people are related to intrinsic and extrinsic skin ageing including androgenic alopecia, seborrheic and actinic keratoses, lentigo, benign skin tumours and xerosis cutis [6, 13, 118]. Further, inflammatory skin diseases and fungal skin infections were reported as highly prevalent, which is also associated with skin ageing [119]. However, the vast majority of studies reported on melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer indicating that there is a much stronger research interest in skin cancer compared to other more frequent diseases. This indicates, that life-limiting diseases may generate higher research interest than improving the quality of life in commoner skin conditions.

Several studies addressed the burden of skin-related concerns and complaints, particularly pruritus, which is a common symptom in older people living at home [120]. The burden of dermatology-related medical visits was also investigated in a number of reports; however, it was often not possible to distinguish between primary care visits and outpatient contacts. Nevertheless, the results suggest that skin-related problems play a large role in seeking health care in community-living older people.

The majority of reports focusing on the effects of interventions described prevention of and screening for ‘skin cancer’. This included screening programmes, prevention campaigns, sun-protection behaviour, or skin cancer knowledge/awareness. One study reported the effects of a teledermatology project in which half of the patients were referred to their primary care physician and the most common prescriptions included self-treatment such as emollients and physician-administered treatments such as topical antifungals, which are applied at home by the individuals themselves or by caregivers [38]. These results suggest that a large proportion may not require specialist dermatological care.

Considering the high and increasing prevalence of the variety of skin conditions and diseases in older people, it seems unlikely that care provided by dermatologists will be feasible either now or in the future for everyone in this population and setting [121]. This relates to questions about who should be responsible for the diagnosis and management of skin conditions in the community. Proposals about possible skin condition categories and care strategies in older people have been made [37, 122]. For example, there appears to be a group of skin conditions that might not have pathological relevance and might not require further treatment (e.g. androgenetic alopecia). Other skin conditions might be manageable either by self-treatment or by other health professionals such as nurses or medical assistants (e.g. xerosis cutis) [122]. At the same time, no need for medical treatment does not mean that the condition does not cause distress or discomfort [123, 124]. The results of our scoping review clearly suggest that the most frequent skin conditions in community-living older people fall into these two broad categories. Nevertheless, there are important diseases, which should be diagnosed and treated by dermatologists (e.g. skin cancer). Approaches such as teledermatology could play an important role in meeting this increasing demand which is in line with the WHO guideline on self-care which promotes self-management, self-screening and self-awareness with the help of health technology, as well as trained healthcare workers facilitating access to such and supporting individuals [125].

Our review found that most research had its origin in Europe, North America and Asia, with the majority providing data on high to high-middle sociodemographic index countries. No study from the continent of Africa was included, only Hahnel et al. [20] included epidemiological data from Tunisia in their review.

The results further indicate that there is a lack of clinical practice guidelines regarding the most frequent skin conditions in older people in community settings. Screened guidelines and Best Practice Recommendations did not include specific recommendations for older people living at home. One might argue that the recommendations of clinical practice guidelines are applicable to all settings and age groups, and that guidelines for community settings are not needed. However, there is a clear need to emphasise basic self-care interventions in older adults such as regular screening or when to seek professional help. At the same time our review results also show, that evidence about the prevention and treatment of major skin conditions in older adults is largely missing [126].

Limitations

We searched in the bibliographic databases MEDLINE, Embase and Epistemonikos, which can be considered most important for our review questions and inclusion criteria and we focussed on current evidence from the last 12 years and ignored older publications. Additional searches in other smaller databases and extending the search period might have led to further hits but overall our results reflect the overall availability of evidence. To keep the number of hits manageable, we only use free text words for the electronic search. Furthermore, as described by Haw, Al-Janabi [127] guidelines may have been missed because a notable number of local guidelines can only be found on websites and are not indexed in electronic library databases. Because this was a scoping review, a risk of bias assessment was not conducted, and the quality of evidence was not evaluated. However, study reporting usually did not follow state-of-the-art methods and there was a substantial heterogeneity of methods and outcome assessments. Although data extraction was performed with the utmost accuracy, some data may be inaccurate due to unclear reporting.

Conclusions

Older community-living people are affected by a high number of skin conditions and diseases, but the current evidence about the burden and effective prevention and treatment strategies is weak. Best practices on how to improve dermatological care in this expanding population are to be determined and there is a particular need for interventional studies to support and to improve skin health at home.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social, Affairs PD (2022) World Population prospects 2022: Summary of results, in (UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3). United Nations, New York

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World Population Ageing 2017, in (ST/ESA/SER.A/408). United Nations, New York

World Health Organization (2015) World report on ageing and health 2015. World Health Organization

World Health Organization (2017) Integrated care for older people. World Health Organization: Geneva

Jafferany M et al (2012) Geriatric dermatoses: a clinical review of skin diseases in an aging population. Int J Dermatol 51(5):509–522

Blume-Peytavi U et al (2016) Age-Associated skin conditions and diseases: current perspectives and future options. Gerontologist 56(Suppl 2):S230–S242

Lintzeri DA et al (2022) Epidermal thickness in healthy humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36(8):1191–1200

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2020) World population ageing 2020 highlights: living arrangements of older persons, in (ST/ESA/SER.A/451). United Nations, New York

Collaborators GBDA (2022) Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease 2019 study. BMJ 376:e068208

Jaul E et al (2018) An overview of co-morbidities and the development of pressure ulcers among older adults. BMC Geriatr 18(1):305

Sanches MM et al (2019) Cutaneous manifestations of diabetes Mellitus and Prediabetes. Acta Med Port 32(6):459–465

Kottner J, Beeckman D (2015) Incontinence-associated dermatitis and pressure ulcers in geriatric patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 150(6):717–729

Kottner J et al (2023) Improving skin health of community-dwelling older people: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 13(5):e071313

Tricco AC et al (2018) PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473

Grey matters (2023) CADTH: Ottawa

Grey matters (2019) A practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Ottawa, CADTH

EASY (2023) Data Archiving and Networked Services

OPENGREY.EU – Grey Literature Database. (2023) OPENGREY

Bramer WM, Milic J, Mast F (2017) Reviewing retrieved references for inclusion in systematic reviews using EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc 105(1):84–87

Hahnel E et al (2017) The epidemiology of skin conditions in the aged: a systematic review. J Tissue Viability 26(1):20–28

Wang Y, Xiao S, Zhang Y (2022) Analysis of disease burden of skin malignant melanoma in China. Chin J Evidence-Based Med 22(5):524–529

Wu J et al (2011) P2-119: Occurrence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the elderly with and without Alzheimer’s disease in the US [abstract], in Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, AAIC 11, Paris, France. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. p. S347

Wu J et al (2011) 698. Risk of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer in Elderly Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease [abstract], in 27th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management, Chicago, United States. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. pp. S303-304

Augustin M et al (2019) Epidemiology of dry skin in the general population [abstract], in 24th World Congress of Dermatology, Milan, Italy

Augustin M et al (2019) Prevalence, predictors and comorbidity of dry skin in the general population. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 33(1):147–150

Flohil SC et al (2013) Prevalence of actinic keratosis and its risk factors in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol 133(8):1971–1978

Mekic S et al (2019) Prevalence and determinants for xerosis cutis in the middle-aged and elderly population: a cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol 81(4):963–969e2

Sanders MGH et al (2018) Prevalence and determinants of seborrhoeic dermatitis in a middle-aged and elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Br J Dermatol 178(1):148–153

Drewitz KP et al (2018) P102 | Prevalence and determinants of Psoriasis in a cross- sectional study of the elderly—results from the German AugUR study [abstract], in 45th Annual Meeting of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Forschung, ADF 2018, Zurich, Switzerland. Experimental Dermatology. pp. e43-44

Drewitz KP et al (2019) P086 | Frequency and comorbidities of eczema in an elderly population in Germany: results from augur [abstract], in 46th Annual Meeting of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Forschung, ADF, Munich, Germany. Experimental Dermatology. pp. e41-42

Drewitz KP et al (2021) Frequency of hand eczema in the elderly: cross-sectional findings from the German AugUR study. Contact Dermat 85(5):489–493

Akbari ME et al (2011) Incidence and survival of cancers in the elderly population in Iran: 2001–2005. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 12(11):3035–3039

Yew YW et al (2020) Psychosocial impact of skin diseases: a population-based study. PLoS ONE 15(12):e0244765

Raghuwanshi AS et al (2022) A cross-sectional study to assess the psychosocial impact of skin diseases. Int J Pharm Clin Res 14(9):1061–1067

Silva ESD, Dumith SC (2019) Non-use of sunscreen among adults and the elderly in southern Brazil. Bras Dermatol 94(5):567–573

Chang C-Y, Park H, Lo-Ciganic J (2020) 3946 | The prevalence of sun protective behaviors across different age groups in the US population: Findings from the 2015 US Health Interview Survey [abstract], in Special Issue: Abstracts of the 36th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, Virtual. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. pp. 306–307

Sinikumpu SP et al (2020) The high prevalence of skin diseases in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 68(11):2565–2571

Bianchi M, Santos A, Cordioli E (2020) Benefits of Teledermatology for geriatric patients: Population-based cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res 22(4):e16700

Tizek L et al (2019) Skin diseases are more common than we think: screening results of an unreferred population at the Munich Oktoberfest. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 33(7):1421–1428

Asokan N, Binesh VG (2017) Cutaneous problems in elderly diabetics: a population-based comparative cross-sectional survey. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 83(2):205–211

Cybulski M, Krajewska-Kulak E (2015) Skin diseases among elderly inhabitants of Bialystok, Poland. Clin Interv Aging 10:1937–1943

Caretti KL, Mehregan DR, Mehregan DA (2015) A survey of self-reported skin disease in the elderly African-American population. Int J Dermatol 54(9):1034–1038

Gontijo Guerra S et al (2014) Skin conditions in community-living older adults: prevalence and characteristics of medical care service use. J Cutan Med Surg 18(3):186–194

Augustin M et al (2011) Prevalence of skin lesions and need for treatment in a cohort of 90 880 workers. Br J Dermatol 165(4):865–873

Lichterfeld-Kottner A et al (2018) Dry skin in home care: a representative prevalence study. J Tissue Viability 27(4):226–231

Iizaka S, Nagata S, Sanada H (2017) Nutritional Status and Habitual Dietary Intake Are Associated with Frail skin conditions in Community-Dwelling Older people. J Nutr Health Aging 21(2):137–146

George LS et al (2017) Morbidity pattern and its sociodemographic determinants among elderly population of Raichur district, Karnataka, India. J Family Med Prim Care 6(2):340–344

Trautmann F et al (2016) Effects of the German skin cancer screening programme on melanoma incidence and indicators of disease severity. Br J Dermatol 175(5):912–919

Cinotti E et al (2016) Skin tumours and skin aging in 209 French elderly people: the PROOF study. Eur J Dermatol 26(5):470–476

Etzkorn JR et al (2013) Identifying risk factors using a skin cancer screening program. Cancer Control 20(4):248–254

Xu Q et al (2023) Trends of non-melanoma skin cancer incidence in Hong Kong and projection up to 2030 based on changing demographics. Ann Med 55(1):146–154

Radkiewicz C et al (2022) Declining Cancer incidence in the Elderly: decreasing Diagnostic Intensity or Biology? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 31(1):280–286

Rodriguez-Betancourt JD, Arias-Ortiz N (2022) Cutaneous melanoma incidence, mortality, and survival in Manizales, Colombia: a population-based study. J Int Med Res 50(6):3000605221106706

Huang J et al (2023) An epidemiological study on skin tumors of the elderly in a community in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep 13(1):4441

Keim U et al (2023) Incidence, mortality and trends of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Germany, the Netherlands, and Scotland. Eur J Cancer 183:60–68

van Niekerk CC et al (2023) Trends in three major histological subtypes of cutaneous melanoma in the Netherlands between 1989 and 2016. Int J Dermatol 62(4):508–513

Botvid SHC et al (2022) Low prevalence of patients diagnosed with psoriasis in Nuuk: a call for increased awareness of chronic skin disease in Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health 81(1):2068111

Choon SE et al (2022) Incidence and prevalence of psoriasis in multiethnic Johor Bahru, Malaysia: a population-based cohort study using electronic health data routinely captured in the Teleprimary Care (TPC(R)) clinical information system from 2010 to 2020: classification: Epidemiology. Br J Dermatol 187(5):713–721

Lu L et al (2022) Global incidence and prevalence of bullous pemphigoid: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cosmet Dermatol 21(10):4818–4835

Matsumoto M et al (2022) Five-year outcomes of a Melanoma Screening Initiative in a large Health Care System. JAMA Dermatol 158(5):504–512

Navsaria L et al (2022) LB911 Incidence and treatments of actinic keratosis in the Medicare population: A cohort study [abstract], in Society for Investigative Dermatology (SID) 2022 Meeting, Portland, United States. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. p. B10

Tang L et al (2021) Prevalence of vitiligo and associated comorbidities in adults in Shanghai, China: a community-based, cross-sectional survey. Ann Palliat Med 10(7):8103–8111

Waldmann A et al (2021) Epidemiologie Von Krebs Im Hohen Lebensalter. best Pract Onkologie 16(12):586–597

Blazek K et al (2022) The impact of skin cancer prevention efforts in New South Wales, Australia: generational trends in melanoma incidence and mortality. Cancer Epidemiol 81:102263

Neena V et al (2021) Prevalence of eczema among older persons: a population-based cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 89(3):426–430

Fors M et al (2020) Actinic keratoses in subjects from la Mitad Del Mundo, Ecuador. BMC Dermatol 20(1):11

Kottner J et al (2020) Prevalence of intertrigo and associated factors: a secondary data analysis of four annual multicentre prevalence studies in the Netherlands. Int J Nurs Stud 104:103437

Prasad S et al (2020) Impact of pressure Injury Prevention Protocol in Home Care services on the prevalence of pressure injuries in the Dubai Community. Dubai Med J 3:99–104

Tokez S et al (2020) Assessment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in situ incidence and the risk of developing invasive cSCC in patients with prior cSCC in situ vs the General Population in the Netherlands, 1989–2017. JAMA Dermatol 156(9):973–981

Tseng HF et al (2020) The epidemiology of herpes zoster in Immunocompetent, unvaccinated adults >/=50 years Old: incidence, complications, hospitalization, mortality, and recurrence. J Infect Dis 222(5):798–806

Bai R et al (2021) Temporal trends in the incidence and mortality of skin malignant melanoma in China from 1990 to 2019. J Oncol 2021:p9989824

Barbieri JS et al (2021) Incidence and prevalence of Granuloma Annulare in the United States. JAMA Dermatol 157(7):824–830

Bucchi L et al (2021) Mid-term trends and recent birth-cohort-dependent changes in incidence rates of cutaneous malignant melanoma in Italy. Int J Cancer 148(4):835–844

Everink IHJ et al (2020) Skin areas, clinical severity, duration and risk factors of intertrigo: a secondary data analysis. J Tissue Viability 30(1):102–107

Madani S et al (2021) Ten-year follow-up of persons with Sun-damaged skin Associated with subsequent development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 157(5):559–565

Memon A et al (2021) Changing epidemiology and age-specific incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma in England: an analysis of the national cancer registration data by age, gender and anatomical site, 1981–2018. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2:100024

Aitken JF et al (2018) Generational shift in melanoma incidence and mortality in Queensland, Australia, 1995–2014. Int J Cancer 142(8):1528–1535

Dziunycz PJ, Schuller E, Hofbauer GFL (2018) Prevalence of Actinic Keratosis in patients Attending General practitioners in Switzerland. Dermatology 234(5–6):214–219

Hu L et al (2018) Trends in the incidence and mortality of cutaneous melanoma in Hong Kong between 1983 and 2015. Int J Clin Exp Med 11(8):8259–8266

Steglich RB et al (2018) Epidemiological and histopathological aspects of primary cutaneous melanoma in residents of Joinville, 2003–2014. Bras Dermatol 93(1):45–53

Sari SP et al (2019) The prevalence of pressure ulcers in community-dwelling older adults: a study in an Indonesian city. Int Wound J 16(2):534–541

Venables ZC et al (2019) Nationwide incidence of metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in England. JAMA Dermatol 155(3):298–306

Venables ZC et al (2019) Epidemiology of basal and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in the U.K. 2013-15: a cohort study. Br J Dermatol 181(3):474–482

Barbaric J, Laversanne M, Znaor A (2017) Malignant melanoma incidence trends in a Mediterranean population following socioeconomic transition and war: results of age-period-cohort analysis in Croatia, 1989–2013. Melanoma Res 27(5):498–502

Kim J et al (2017) Incidence of pressure ulcers during Home and Institutional Care among Long-Term Care Insurance beneficiaries with dementia using the Korean Elderly Cohort. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 18(7): p. 638 e1-638 e5.

Pandeya N, Olsen CM, Whiteman DC (2017) The incidence and multiplicity rates of keratinocyte cancers in Australia. Med J Aust 207(8):339–343

Thorslund K et al (2017) Incidence of bullous pemphigoid in Sweden 2005–2012: a nationwide population-based cohort study of 3761 patients. Arch Dermatol Res 309(9):721–727

Abuabara K et al (2018) The prevalence of atopic eczema across the lifespan: a U.K. population-based cohort study [abstract], in Abstracts of the 10th George Rajka International Symposium on Atopic Dermatitis, Utrecht, Netherlands. British Journal of Dermatology. p. e58

Hsieh C-F, Huang W-F, Chiang Y-T 157. The Incidence of Actinic Keratosis and Risk of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer in Taiwan [abstract], in 30th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management, Taipei, Taiwan. 2014, Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. pp. 84–85

Duim E et al (2015) Prevalence and characteristics of lesions in elderly people living in the community. Rev Esc Enferm USP 49(Spec No):51–57

Kiiski V et al (2015) 086 Is atopic dermatitis more persistent than previously estimated? [abstract], in 45th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Dermatological Research, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. p. S15

Romani L et al (2015) Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 15(8):960–967

Hsieh C-F et al (2016) A Nationwide Cohort Study of Actinic Keratosis in Taiwan*. Int J Gerontol 10(4):218–222

Tseng HW et al (2016) Risk of skin cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. Med (Baltim) 95(26):e4070

Paul C et al (2011) Prevalence and risk factors for xerosis in the elderly: a cross-sectional epidemiological study in primary care. Dermatology 223(3):260–265

Ritchie SR et al (2011) Demographic variation in community-based MRSA skin and soft tissue infection in Auckland, New Zealand. N Z Med J, 124(1332)

Hollestein LM et al (2012) Trends of cutaneous melanoma in the Netherlands: increasing incidence rates among all Breslow thickness categories and rising mortality rates since 1989. Ann Oncol 23(2):524–530

Joly P et al (2012) Incidence and mortality of bullous pemphigoid in France. J Invest Dermatol 132(8):1998–2004

Bonaccorsi G et al (202) Impact of different pads in elderly assisted in home care [abstract]. 43rd Annual Meeting Int Cont Soc ICS 2013 Barcelona Spain 2013(Neurourol Urodyn):p802–803

Danielsen K et al (2013) Is the prevalence of psoriasis increasing? A 30-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. Br J Dermatol 168(6):1303–1310

Robsahm TE et al (2013) Sex differences in rising trends of cutaneous malignant melanoma in Norway, 1954–2008. Melanoma Res 23(1):70–78

Frese T, Herrmann K, Sandholzer H (2011) Pruritus as reason for encounter in general practice. J Clin Med Res 3(5):223–229

Henchoz Y et al (2017) Chronic symptoms in a representative sample of community-dwelling older people: a cross-sectional study in Switzerland. BMJ Open 7(1):e014485

Cowdell F et al (2018) Self-reported skin concerns: an epidemiological study of community-dwelling older people. Int J Older People Nurs 13(3):e12195

Yong SS et al (2020) Self-reported generalised pruritus among community-dwelling older adults in Malaysia. BMC Geriatr 20(1):223

Hay RJ, Fuller LC (2015) Global burden of skin disease in the elderly: a grand challenge to skin health. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 150(6):693–698

Wysong A et al (2013) Nonmelanoma skin cancer visits and procedure patterns in a nationally representative sample: national ambulatory medical care survey 1995–2007. Dermatol Surg 39(4):596–602

Landis ET et al (2014) Top dermatologic diagnoses by age. Dermatol Online J 20(4):22368

Liu T, Brienza R (2016) What brings an older veteran to an urgent visit (UV) A review of the chief concerns by veterans aged 65 and older who presented for uv durin a 6-month period at the West Haven Veteran Affairs Center of excellence in Primary Care Education (VA COEPCE), an interprofessional academic patient aligned care team (PACT) [abstract], in Abstracts from the 2016 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting. J Gen Intern Med. pp. S468-469

Lee HJ et al (2017) Effects of home-visit nursing services on hospitalization in the elderly with pressure ulcers: a longitudinal study. Eur J Public Health 27(5):822–826

Gontijo Guerra S et al (2014) Association between skin conditions and depressive disorders in community-dwelling older adults. J Cutan Med Surg 18(4):256–264

Karimkhani C et al (2017) The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the global burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis 17(12):1247–1254

Meyers JL et al (2019) Costs of herpes zoster complications in older adults: a cohort study of US claims database. Vaccine 37(9):1235–1244

Okuno Y et al (2013) Assessment of skin test with varicella-zoster virus antigen for predicting the risk of herpes zoster. Epidemiol Infect 141(4):706–713

Sideris E, Thomas SJ (2020) Patients’ sun practices, perceptions of skin cancer and their risk of skin cancer in rural Australia. Health Promot J Austr 31(1):84–92

Alexandridou M, Bollaerts K (2017) Pin10 Zoster Vaccine Effectiveness against incident herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in elderly in the UK [abstract], in ISPOR 20th Annual European Congress, Glasgow, United Kingdom. Value Health. p. A780

Karimkhani C et al (2017) Global skin Disease Morbidity and Mortality: an Update from the global burden of Disease Study 2013. JAMA Dermatol 153(5):406–412

Al-Nuaimi Y, Sherratt MJ, Griffiths CE (2014) Skin health in older age. Maturitas 79(3):256–264

Chang AL et al (2013) Geriatric dermatology review: major changes in skin function in older patients and their contribution to common clinical challenges. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14(10):724–730

Weisshaar E, Mettang T (2018) [Pruritus in elderly people-an interdisciplinary challenge]. Hautarzt 69(8):647–652

Sreekantaswamy SA, Shahin TB, Butler DC (2020) COMMENTSBridging the gap: Commentary on the high prevalence of skin diseases in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 68(12):2967–2968

Kottner J (2023) Nurses as skin care experts: do we have the evidence to support practice? Int J Nurs Stud 145:104534

Sinikumpu SP, Huilaja L (2020) Reply to: bridging the gap: Commentary on the high prevalence of skin diseases in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 68(12):2968–2969

Gupta MA, Gilchrest BA (2005) Psychosocial aspects of aging skin. Dermatol Clin 23(4):643–648

Organization WH (2022) WHO guideline on self-care interventions for thealth and well-being, 2022 revision. Geneva, World Health Organization

Fastner A, Hauss A, Kottner J (2023) Skin assessments and interventions for maintaining skin integrity in nursing practice: an umbrella review. Int J Nurs Stud 143:104495

Haw WY et al (2021) Global guidelines in Dermatology Mapping Project (GUIDEMAP): a scoping review of dermatology clinical practice guidelines. Br J Dermatol 185(4):736–744

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was funded by the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS).

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JK, UBP and CG planned and supervised the study. AF and DL performed the searches and data extractions. AF and DL prepared the tables and figures. AF and JK wrote and revised the main manuscript text. CG, UBP and DL critically revised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Ulrike Blume-Peytavi received consulting fees from Abbvie, Boots Healthcare, Cantabria Labs, CeraVe, Dermocosmétique Vichy, Galderma Laboratorium GmbH, Eli Lilly, Laboratoires Bailleuil, Pfizer, Sanofi Regeneron. Christopher E. M. Griffiths received consulting fees from Walgreens Boots Alliance and is a director of CGSkin. Jan Kottner received consulting fees from Hartmann, Mölnlycke, Arjo.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kottner, J., Fastner, A., Lintzeri, DA. et al. Skin health of community-living older people: a scoping review. Arch Dermatol Res 316, 319 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-03059-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-03059-0