Abstract

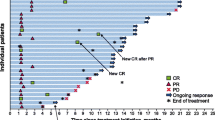

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a neuroendocrine skin cancer with a high rate of mortality. While still relatively rare, the incidence of MCC has been rapidly rising in the US and around the world. Since 2017, two immunotherapeutic drugs, avelumab and pembrolizumab, have been FDA-approved for the treatment of metastatic MCC and have revolutionized outcomes for MCC. However, real-world outcomes can differ from clinical trial data, and the adoption of novel therapeutics can be gradual. We aimed to characterize the treatment practices and outcomes of patients with metastatic MCC across the US. A retrospective cohort study of adult cases of MCC in the National Cancer Database diagnosed from 2004 to 2019 was performed. Multivariable logistic regressions to determine the association of a variety of patient, tumor, and system factors with likelihood of receipt of systemic therapies were performed. Univariate Kaplan–Meier and multivariable Cox survival regressions were performed. We identified 1017 cases of metastatic MCC. From 2017 to 2019, 54.2% of patients received immunotherapy. This increased from 45.1% in 2017 to 63.0% in 2019. High-volume centers were significantly more likely to use immunotherapy (odds ratio 3.235, p = 0.002). On univariate analysis, patients receiving systemic immunotherapy had significantly improved overall survival (p < 0.001). One-, 3-, and 5-year survival was 47.2% (standard error [SE] 1.8%), 21.8% (SE 1.5%), and 16.5% (SE 1.4%), respectively, for patients who did not receive immunotherapy versus 62.7% (SE 3.5%), 34.4% (SE 3.9%), and 23.6% (SE 4.4%), respectively, for those who did (Fig. 1). In our multivariable survival regression, receipt of immunotherapy was associated with an approximately 35% reduction in hazard of death (hazard ratio 0.665, p < 0.001; 95% CI 0.548–0.808). Our results demonstrate that the real-world survival advantage of immunotherapy for metastatic MCC is similar to clinical trial data. However, many patients with metastatic disease did not receive this guideline-recommended therapy in our most recent study year, and use of immunotherapy is higher at high-volume centers. This suggests that regionalization of care to high-volume centers or dissemination of their practices, may ultimately improve patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, Sagy N, Schwartz AM, Henson DE (2010) Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol 37(1):20–27

Eisemann N, Jansen L, Castro FA et al (2016) Survival with nonmelanoma skin cancer in Germany. Br J Dermatol 174(4):778–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14352

American Cancer Society (2023) Cancer facts & figures 2023

Youlden DR, Soyer HP, Youl PH, Fritschi L, Baade PD (2014) Incidence and survival for Merkel cell carcinoma in Queensland, Australia, 1993–2010. JAMA Dermatol 150(8):864–872. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.124

Kieny A, Cribier B, Meyer N, Velten M, Jegu J, Lipsker D (2018) Epidemiology of Merkel cell carcinoma. A population-based study from 1985 to 2013, in Northeastern of France. Int J Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31860

Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA et al (2018) Merkel cell carcinoma: current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol 78(3):457-463.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028

Olsen CM, Pandeya N, Whiteman DC (2021) International increases in Merkel cell carcinoma incidence rates between 1997 and 2016. J Invest Dermatol 141(11):2596-2601.e1

Zaar O, Gillstedt M, Lindelöf B, Wennberg-Larkö AM, Paoli J (2016) Merkel cell carcinoma incidence is increasing in Sweden. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 30(10):1708–1713

Baker M, Cordes L, Brownell I (2018) Avelumab: a new standard for treating metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 18(4):319–326

Desch L, Kunstfeld R (2013) Merkel cell carcinoma: chemotherapy and emerging new therapeutic options. J Skin Cancer 2013:327150. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/327150

Lemos BD, Storer BE, Iyer JG et al (2010) Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. J Am Acad Dermatol 63(5):751–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.056

D’Angelo SP, Lebbé C, Mortier L et al (2021) First-line avelumab in a cohort of 116 patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (JAVELIN Merkel 200): primary and biomarker analyses of a phase II study. J Immunother Cancer 9(7):e002646

Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ et al (2021) Three-year survival, correlates and salvage therapies in patients receiving first-line pembrolizumab for advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 9(4):e002478

Kim S, Wuthrick E, Blakaj D et al (2022) Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab with or without stereotactic body radiation therapy for advanced Merkel cell carcinoma: a randomised, open label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet 400(10357):1008–1019

Richardson PG, San Miguel JF, Moreau P et al (2018) Interpreting clinical trial data in multiple myeloma: translating findings to the real-world setting. Blood Cancer J 8(11):109

Sankar K, Bryant AK, Strohbehn GW et al (2022) Real world outcomes versus clinical trial results of durvalumab maintenance in veterans with stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers (Basel) 14(3):614

Lakdawalla DN, Shafrin J, Hou N et al (2017) Predicting real-world effectiveness of cancer therapies using overall survival and progression-free survival from clinical trials: empirical evidence for the ASCO value framework. Value Health 20(7):866–875

Cramer-van der Welle CM, Verschueren MV, Tonn M et al (2021) Real-world outcomes versus clinical trial results of immunotherapy in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in the Netherlands. Sci Rep 11(1):1–9

Hanna N, Trinh Q-D, Seisen T et al (2018) Effectiveness of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in the current real world setting in the USA. Eur Urol Oncol 1(1):83–90

Bhatia S, Nghiem P, Veeranki SP et al (2022) Real-world clinical outcomes with avelumab in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma treated in the USA: a multicenter chart review study. J Immunother Cancer 10(8):e004904

Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY (2008) The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 15(3):683–690. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3

Mallin K, Browner A, Palis B et al (2019) Incident cases captured in the National Cancer Database compared with those in US Population Based Central Cancer Registries in 2012–2014. Ann Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-019-07213-1

Cheraghlou S, Doudican NA, Criscito MC, Stevenson ML, Carucci JA (2023) Overall survival after mohs surgery for early-stage Merkel cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 159(10):1068–1075. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2822

Sinnamon AJ, Neuwirth MG, Yalamanchi P et al (2017) Association between patient age and lymph node positivity in thin melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 153(9):866–873

Danish HH, Patel KR, Switchenko JM et al (2016) The influence of postoperative lymph node radiation therapy on overall survival of patients with stage III melanoma, a National Cancer Database analysis. Melanoma Res 26(6):595–603. https://doi.org/10.1097/cmr.0000000000000292

Cheraghlou S, Agogo GO, Girardi M (2019) Evaluation of lymph node ratio association with long-term patient survival after surgery for node-positive Merkel cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 155(7):803–811. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0267

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control 19(6):716–723

D’Angelo S, Bhatia S, Brohl A et al (2021) Avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (JAVELIN Merkel 200): updated overall survival data after> 5 years of follow-up. ESMO open 6(6):100290

D’Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbé C et al (2018) Efficacy and safety of first-line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic merkel cell carcinoma: a preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 4(9):e180077. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0077

Monson JR, Probst CP, Wexner SD et al (2014) Failure of evidence-based cancer care in the United States: the association between rectal cancer treatment, cancer center volume, and geography. Ann Surg 260(4):625–632

Wright JD, Neugut AI, Ananth CV et al (2013) Deviations from guideline-based therapy for febrile neutropenia in cancer patients and their effect on outcomes. JAMA Intern Med 173(7):559–568

Dudeja V, Gay G, Habermann EB et al (2012) Do hospital attributes predict guideline-recommended gastric cancer care in the United States? Ann Surg Oncol 19(2):365–372. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-011-1973-z

Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (2013) Adherence to treatment guidelines for ovarian cancer as a measure of quality care. Obstet Gynecol 121(6):1226–1234

Brannstrom F, Bjerregaard JK, Winbladh A et al (2015) Multidisciplinary team conferences promote treatment according to guidelines in rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 54(4):447–453. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186x.2014.952387

Shah BA, Qureshi MM, Jalisi S et al (2016) Analysis of decision making at a multidisciplinary head and neck tumor board incorporating evidence-based National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines. Pract Radiat Oncol 6(4):248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2015.11.006

Cheraghlou S, Agogo GO, Girardi M (2023) The impact of facility characteristics on Merkel cell carcinoma outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 89(1):70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.058

Cheraghlou S, Ugwu N, Girardi M (2023) Treatment at high-volume facilities is associated with improved overall survival for patients with cutaneous B cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 88(1):203–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2022.04.032

Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, Stukel TA (2007) Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg 245(5):777

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV et al (2002) Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 346(15):1128–1137

Cheraghlou S, Christensen SR, Leffell DJ, Girardi M (2021) Association of treatment facility characteristics with overall survival after mohs micrographic surgery for T1a–T2a invasive melanoma. JAMA Dermatol 157(5):531–539. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0023

Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE (2000) Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 18(11):2327–2340

Cheraghlou S, Agogo GO, Girardi M (2019) Treatment of primary nonmetastatic melanoma at high-volume academic facilities is associated with improved long-term patient survival. J Am Acad Dermatol 80(4):979–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.026

Roohan PJ, Bickell NA, Baptiste MS, Therriault GD, Ferrara EP, Siu AL (1998) Hospital volume differences and five-year survival from breast cancer. Am J Public Health 88(3):454–457

Cheraghlou S, Kuo P, Judson BL (2017) Treatment delay and facility case volume are associated with survival in early-stage glottic cancer. Laryngoscope 127(3):616–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26259

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC, VP, and NK performed the analysis and drafted the text. ND and JC revised the work and provided oversight.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures, and all authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

IRB

Deemed not to be human subjects research and therefore exempt from IRB review by the NYU Langone IRB.

Patient consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheraghlou, S., Pahalyants, V., Jairath, N.K. et al. High-volume facilities are significantly more likely to use guideline-adherent systemic immunotherapy for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: implications for cancer care regionalization. Arch Dermatol Res 316, 86 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-02817-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-024-02817-4