Abstract

Introduction

Many professional football players sustain at least one severe injury over the course of their career. Because detailed epidemiological data on different severe injuries in professional football have been missing so far, this study describes the frequency and return-to-competition (RTC) periods of different types of severe football injuries.

Material and methods

This epidemiological investigation is a prospective standardised injury analysis based on national media longitudinal registration. Injuries were classified according to the consensus statement by Fuller et al. (2006). The analysis includes injuries sustained by players of the first German football league during the seasons 2014–2015 to 2017–2018. Level of evidence: II.

Results

Overall, 660 severe injuries were registered during the four seasons (mean 165 per season; 9.2 per season per team; incidence in 1000 h: 0.77). The body region most frequently affected by severe injury was the knee (30.0%; 49.5 injuries per season/SD 13.2) followed by the thigh (26.4%; 43.5 injuries/SD 4.2) and the ankle (16.7%; 27.5 injuries/SD 5.0). The distribution of injuries over the course of a season showed a trend for ACL ruptures to mainly occur at the beginning of a season (45.8%), overuse syndromes such as achillodynia (40.9%) and irritation of the knee (44.4%) during the winter months and severe muscle and ankle injuries at the end of a season. ACL ruptures showed the longest RTC durations (median 222 days).

Conclusion

This study presents detailed epidemiological data on severe injuries in professional football. The body region most frequently affected by severe injuries was the knee. Several types of severe injuries showed a seasonal injury pattern. The appropriate timing of RTC after an injury is one of the most important and complex decisions to be made. This study provides information on the typical time loss due to specific severe football injuries, which may serve as a guideline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Severe injuries are common in football and lead to considerable absence from training and competition [31]. They represent a serious problem for football players and clubs because of negative consequences such as absence from competition, potentially required surgical treatment or impaired physical performance after rehabilitation and re-integration. The epidemiology of some severe injuries in professional football, in particular ACL ruptures, has been well described in the literature [6, 20, 23]. Injury mechanisms and patterns as well as differences between age groups and genders have also been published for ACL injuries [5, 7, 16, 19, 20, 32] but less frequently for other types of severe injuries. Epidemiological information represents an important source for understanding the circumstances of an injury and for identifying the relevant risk factors and influencing factors [1, 26]. Epidemiological injury analyses in sports are generally aimed at furthering injury prevention strategies. Because of the negative consequences of severe football injuries their prevention has become highly important in professional football to reduce the days of absence and thus, to increase the availability of players—both essential factors for the success of a professional football team [8, 15].

Another important aspect of injury prevention in professional football is preventing re-injury after an index injury. Such re-injuries frequently occur after ACL injuries [31, 32] or muscle injuries [9, 30] and often result in a long absence from competition. The prevention of such re-injuries contains different targets during the rehabilitation phase, the re-integration of the player to training sessions as well as the decision about return-to-competition (RTC) in official matches [14]. Such decisions belong to secondary and tertiary prevention strategies and include the consideration of the most influential injury factors, mainly insufficient physical preparation [17, 18] and neuromotorical deficits due to a prematurely finished rehabilitation or early RTC after a previous injury [22]. In professional football, the decision on timing the RTC plays a crucial role because premature competition may result in re-injury or further complications. Criteria-based rehabilitation was recently published as an advancement compared to solely time-based rehabilitation [29] and both are used in the daily routine of current rehabilitation strategies after injuries. Detailed knowledge about the healing and rehabilitation phase of injuries, particularly of severe football injuries, is an essential part of injury management in professional football. The duration of absence and the timing of RTC for some specific injuries in professional football are well-known, especially in the case of ACL ruptures [24, 25, 28]. A recent study by Ekstrand et al. (2019) for the first time described a larger list of RTC timings for the 31 most frequent types of injury in the UEFA Champions League population [10]. However, severe injuries may be less frequent in “ordinary” professional football than in the UEFA Champions League. Severe injuries with longer time-out than 4 weeks in professional football player were less included in the above-mentioned study [10] and thus became the objective of the present study.

This study investigated all severe injuries in the German first football league that resulted in absence of more than 28 days [12]. The investigation was conducted by means of a national prospective injury registration in a standardised manner [19]. For the first time, the aim of this study was to investigate the frequency of severe injuries in national professional football and the subsequent length of absence from football. Among its objectives was to find out whether knee injuries represent the most frequent injury type in professional football and what the typical time loss is in these cases.

Methods

This prospective cohort study (level of evidence: II) investigated severe football injuries in the first professional league in Germany (‘1st Bundesliga’) in longitudinal manner. The analysis only included injury types that resulted in absence from official football matches of at least 28 days and were therefore categorized as “severe” [12]. Data assessment only considered players with at least one official match during one of the seasons between 2014–2015 and 2017–2018. All injuries sustained in training sessions and official matches for clubs and national teams were included. Injuries were excluded if data definition by multiple media sources were not valid if absence from football matches were less than 28 days or injuries happened in players of a team, who played no single match during the season.

Injury data provided by medical staff and players are rarely available for several years as required for longitudinal studies. Therefore, injury data were prospectively documented in a standardised manner [19] by means of data obtained from the German kicker® sports magazine that is published on a twice-weekly basis. Each professional football team has an assigned journalist who updates team-specific information. Additionally, we registered and analysed injuries by screening the social media websites (Facebook® and Twitter®) of every first league team and players themselves as well as the online platform http://www.transfermarkt.de on a daily basis. Each registration of an injury in the database was followed by a verification process, and each information was confirmed by at least one other source. The diagnosis of registered injuries is best verified by medical staff according to the international guidelines [12, 13] as recently carried out by this study group [2, 3, 11, 20]. In the current study, the recently published standards for accurate injury registration by media analysis [19] were used to confirm the validity of media-based data (Table 1).

Injury types with the same diagnoses were collected and demonstrated in this study for affected body region, occurred injury type and seasonal distribution. For the illustration of the return to competition timing, selected this study the most frequent 45 specific injuries and injuries with a specified diagnosis and only these injuries were included in this question. In addition to injury patterns, the current study also investigated the distribution of specific football injuries over the course of a season. Injury incidence was measured in 1000 football hours (h) of training, match and overall exposure (training and match injuries combined). Official sports media provide valid information about the match exposure of every football player over the course of a season. However, this is not the case for training exposure that is why it was calculated according to previous publications by the authors wherein the same study population within a different study period (seasons 2008–2010) was used and to own experience due to playing at professional football levels [2, 19]. Based on this, training exposure was calculated to average 7200 h per team per year and 340 h per player a year. The average match exposure amounted to 50 h per season. RTC timings were calculated from the day of injury to playing the first official match-information that is reliably available from public media.

Because the entire data pool was exclusively derived from publicly available media data on injuries and players, this study did not have to be approved by the local Ethics Committee. Continuous data are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD) and categorical data as frequency counts (percentages). Injury classification for tables was inspired by OSICS/Orchard sports injury classification system.. All analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.0 and R (version 3.3.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

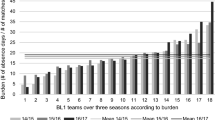

Overall, 660 severe injuries occurred during the study period of four ‘Bundesliga’ seasons (mean 165 per season or 9.2 per season per team, injury incidence in 1000 h football exposure 0.77). The frequency of severe injuries among all injuries varied over the study period between 22.7 and 28.0% (Fig. 1). The mean age of the injured players was 26.3 years (SD 4.0) Injury distribution according to playing position is displayed in Table 2.

The body region most frequently affected by severe injuries was the knee joint (30.0%; 49.5 injuries per season/SD 13.2) followed by the thigh (26.4%; 43.5 injuries per season/SD 4.2), the ankle region (16.7%; 27.5 injuries per season/SD 5.0) and the lower leg (6.2%; 10.3 injuries per season/SD 2.8). 5 severe head traumas like concussion with combined midfacial fractures (5 cases) also led to severe injuries (Table 3). The most frequent specific severe injuries in professional football were muscle tears (19.8%) and tendons rupture of the thigh (5.3%), lateral ligament injuries of the ankle (6.5%) and medial collateral ligament injuries of the knee joint (5.1%). Only two out of the 16 most common severe injury types did not affect the lower limbs, one was located at the lower back (low back pain) and one at the acromioclavicular joint (dislocation: 2.4% each) (Table 4).

Seasonal distribution showed a trend towards an increasing frequency of muscles tears at the end of the season (March–May 36.6%). Similar results were found for thigh muscle pain (March–April 30.7%) and lateral ankle ligament ruptures (April 22.2%). The frequency of ACL injuries was higher at the beginning of the seasons (Aug–Sept 45.8%). Overuse injuries such as achillodynia (Dec–Jan 40.9%) or ‘irritation of the knee’ (Nov–Jan 55.5%) mainly occurred during the winter months (Fig. 2a, b).

For the calculation of RTC timings in specific diagnoses, 109 injuries were excluded as no specific diagnosis could be established. The remaining 551 injuries (137.8 injuries per season/SD 12.7) could be grouped in 45 specific injury diagnoses. Of the 45 types of specific injury diagnosis for the RTC calculation, 12 affected the knee joint and 7 the ankle. The injury type with the longest median absence of all severe injuries was an ACL rupture, it lasted 222 days. Other knee injuries involving absence from football of more than three months were cartilage injury of the knee joint, a PCL (posterior cruciate ligament) rupture and a rupture of the patellar tendon. Further injuries with long absence were a cartilage damage of the hip joint, a disc prolapse, a rupture of the Achilles tendon, a medial ligament injury of the ankle and fractures of the ankle or fibula shaft. Other fractures such as face, upper extremities, ribs or clavicle fractures showed shorter RTC times of less than 2 months (Table 5).

Discussion

For the first time, this study provides longitudinal prospective data on severe injuries in national professional football. Epidemiological injury reports so far have only covered a few types of injury, such as ACL injury [19, 20, 31] or concussion [3, 4, 27]. This study describes the injury incidence, the injury frequency over the course of a season and the RTC times of several severe injuries in professional football in detail.

Frequency of severe injuries in professional football

The frequency of specific types of severe injury in this cohort resembles those found in previous studies, for instance for ACL ruptures [19, 31], fractures [21] and muscle injuries [9]. A new and important addition to the current knowledge is the finding that normally less severe injuries such as concussions with a mean absence from professional football of just a few days [3, 4, 10] and a recommended period for a safe return-to-play of 7 days can also result in long absences from football when combined with midfacial fractures. Some injury types seem to peak at a specific time of the season. Such knowledge is important to better understand the influencing factors for the occurrence of injuries as a basis for well-balanced and well-timed prevention strategies. It has been shown that ACL injuries seem to require prevention strategies before the beginning of a season as they peak at that time [20]. The current study presents novel knowledge on the distribution of other types of severe injuries over the course of a season, too. The steady increase in the number of severe muscle and ankle injuries towards the end of a season could be a consequence of a football season’s cumulated stressors and, thus, a result of fatigue and overstress of the muscles and reduced neuromotor adaptation of the joints. The increased frequency of overuse injuries in the winter months raises the suspicion that temperature changes and pitch conditions may have an impact.

Return-to-football after a severe injury

So far, only Ekstrand et al. (2019) have provided a detailed list of RTC times of different football injuries [10]. The mean RTC timings in the UEFA European football level seems to show bit faster RTC timings, e.g. in case of ACL injuries, compared to national professional football in this study. This study gives RTC data for 45 different specific types of injury in professional football representing the largest number of RTC times that has been published so far. Such publications are important: despite the novel development of criteria-based rehabilitation after injury, which includes repeated testing of different parameters and specific criteria on RTC [29], team doctors, sports physicians and sports physiotherapists in football benefit from knowing the time range between minimum and maximum RTC times for individual injuries, particularly in the case of less frequent (and therefore less familiar) severe ones. Such knowledge represents valuable information also for non-medicals like the player as well as for the team (coach) and the club [22]. Additionally, the RTC times of different injuries in such cohort of professional football may also be used as a minimum benchmark for the RTC time after specific injuries of amateur football players. It seems to be unrealistic to expect amateur footballers to benefit from the same RTC timings after injury as professionals. Amateur football has shown in previous studies higher re-injury rates compared to professional football [14], which underlines the potential benefit of guiding values for RTC at these levels.

Perspectives for injury prevention

Preventing severe injuries is essential for further development of modern football with increasing professionalism worldwide [20], for reducing numbers and duration of injuries and their potentially subsequent long-term health sequelae and for lowering the dropout rate of injured player and health costs [8, 15]. Knowledge about frequency and potential influencing factors is the basis for developing suitable prevention strategies [1]. This study not only provides advanced knowledge about factors influencing severe injuries as part of primary prevention but contains also helpful information on RTC times as part of secondary prevention. According to this study, knee injuries often have to be classified as severe as they frequently cause a time loss of more than 4 weeks. This does not solely refer to traumatic injuries but to overuse injuries alike examples being ‘irritations of the knee’ or an isolated meniscal injury. For a prevention strategy, the timing of injuries during the season is valuable to know, as some injuries occur mainly at the beginning of the season (e.g. ACL), some during the winter months (e.g. irritation).

Methodology and limitations

Previous media-based studies often had some limitations with regard to the definition of injuries as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may have led to imprecise injury statistics and debatable conclusions. The current study population was evaluated by means of an advanced national, regional and local media analysis with strict exclusion criteria and validation process (Table 1) [19, ]. As this media-based analysis was prospectively conducted over 4 years, which simplified the injury recording process as the most detailed information can be obtained immediately after the occurrence of an injury. Therefore, the strengths of this study are the verification of the injury diagnosis by different public sources, its precisely defined methodology and its differentiation between valid and weak information on professional football players. Injury and RTC times of severe injuries can be validly documented via media sources. Nevertheless, the gold standard of injury registration in football remains injury reports provided by the clubs’ medical staff, (which is also not free from limitations itself of course). Not just ACL injuries [19] also other severe injuries showed high external validity in the verification process. Only a minority (16.5%) of registered media-based injuries had to be excluded for the calculation of RTC timings. Furthermore, media analysis allows for a very good estimate of the match injury incidence analysis and a good estimation of the training exposure as shown in earlier publications in the same study population [2, 3, 19]. Media-based data should be critically enquired and validated against various media sources for each single injury.

Conclusion

For the first time, this study presents epidemiological data of severe injuries of professional football players. Severe injuries with a long period of time-out in football mainly affected the knee. There is a seasonal accumulation of ACL injuries at the beginning of the season. The appropriate timing of return-to-competition after an injury is one of the most important and complex decisions to be made by the medical team. Knowledge about the typical time loss may serve as a guideline, particularly in the case of uncommon injuries or less experienced medical staff.

References

Alentorn-Geli E, Myer GD, Silvers HJ, Samitier G, Romero D, Lazaro-Haro C, Cugat R (2009) Prevention of non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer players. Part 1: Mechanism of injury and underlying risk factors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17:705–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-0813-1

aus der Fünten K, Faude O, Lensch J, Meyer T (2014) Injury characteristics in the German professional male soccer leagues after a shortened winter break. J Athl Train 49:786–793. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.51

Beaudouin F, Aus der Fünten K, Tröß T, Reinsberger C, Meyer T (2017) Head injuries in professional male football (soccer) over 13 years: 29% lower incidence rates after a rule change (red card). Br J Sports Med 53:948–952. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097217

Beaudouin F, der Fünten KA, Tröß T, Reinsberger C, Meyer T (2019) Time trends of head injuries over multiple seasons in professional male football (Soccer). Sports Med Int Open 28:E6–E11. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0808-2551

Bisciotti GN, Chamari K, Cena E, Bisciotti A, Bisciotti A, Corsini A, Volpi P (2019) Anterior cruciate ligament injury risk factors in football: a narrative review. J Sports Med Phys Fitn 59:1724–1738. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.19.09563-X

Bjordal JM, Arnöy F, Hannestad B, Strand T (1997) Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. Am J Sports Med 25:341–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659702500312

Brophy R, Silvers HJ, Gonzales T, Mandelbaum BR (2010) Gender influences: the role of leg dominance in ACL injury among soccer players. Br J Sports Med 44:694–697. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051243

Ekstrand J (2013) Keeping your top players on the pitch: the key to football medicine at a professional level. Br J Sports Med 47:723–724. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092771

Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M (2011) Epidemiology of muscle injuries in professional football (soccer). Am J Sports Med 39:1226–1232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546510395879

Ekstrand J, Krutsch W, Spreco A, van Zoest W, Roberts C, Meyer T, Bengtsson H (2019) Time before return to play for the most common injuries in professional football: a 16-year follow-up of the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br J Sports Med 54:421–426. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100666

Faude O, Meyer T, Federspiel B, Kindermann W (2009) Injuries in elite German football—a media-based analysis. Dtsch Z Sportmed 60:139–144

Fuller CW, Ekstrand J, Junge A, Andersen TE, Bahr R, Dvorak J, Hägglund M, McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH (2006) Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Clin J Sports Med 16:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042752-200603000-00003

Hägglund M, Waldén M, Bahr R, Ekstrand J (2005) Methods for epidemiological study of injuries to professional football players: developing the UEFA model. Br J Sports Med 39:340–346. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.018267

Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J (2016) Injury recurrence is lower at the highest professional football level than at national and amateur levels: does sports medicine and sports physiotherapy deliver? Br J Sports Med 50:751–758. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095951

Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, Kristenson K, Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J (2013) Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 47:738–742. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215

Hewett TE, Ford KR, Hoogenboom BJ, Myer GD (2010) Understanding and preventing ACL injuries: current biomechanical and epidemiologic considerations—update 2010. N Am J Sprots Phys Ther 5:234–251 (PMID: 21655382)

Koch M, Zellner J, Berner A, Grechenig S, Krutsch V, Nerlich M, Angele P, Krutsch W (2016) Influence of preparation and football skill level on injury incidence during an amateur football tournament. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 136:353–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-015-2350-3

Krutsch V, Clement A, Heising T, Achenbach L, Zellner J, Gesslein M, Weber-Spickschen S, Krutsch W (2019) Influence of poor preparation and sleep deficit on injury incidence in amateur small field football of both gender. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 140:457–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-019-03261-0

Krutsch W, Memmel C, Krutsch V, Angele P, Tröß T, Aus der Fünten K, Meyer T (2019) High return to competition rate following ACL injury—a 10-year media-based epidemiological injury study in men’s professional football. Eur J Sport Sci 18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1648557

Krutsch W, Zeman F, Zellner J, Pfeifer C, Nerlich M, Angele P (2016) Increase in ACL and PCL injuries after implementation of a new professional football league. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:2271–2279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3357-y

Larsson D, Ekstrand J, Karlsson MK (2016) Fracture epidemiology in male elite football players from 2001 to 2013: ‘how long will this fracture keep me out?’ Br J Sports Med 50:759–763. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095838

Loose O, Achenbach L, Fellner B, Lehmann J, Jansen P, Nerlich M, Angele P, Krutsch W (2018) Injury prevention and return to play strategies in elite football: no consent between players and team coaches. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 138(7):985–992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-018-2937-6 (Epub 2018 Apr 20)

Lundblad M, Waldén M, Hägglund M, Ekstrand J, Thomeé C, Karlsson J (2016) No association between return to play after injury and increased rate of anterior cruciate ligament injury in men’s professional soccer. Orthop J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967116669708

Mai HT, Chun DS, Schneider AD, Erickson BJ, Freshman RD, Kester B, Verma NN, Hsu WK (2017) Performance-based outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in professional athletes differ between sports. Am J Sports Med 45:2226–2232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517704834

Mohtadi NG, Chan DS (2018) Return to sport-specific performance after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 46:3307–3316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517732541

MOON Knee Group, Spindler KP, Huston LJ, Chagin KM, Kattan MW, Reinke EK, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Brophy RH, Cox CL, Dunn WR, Flanigan DC, Jones MH, Kaeding CC, Magnussen RA, Marx RG, Matava MJ, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Pedroza AD, Vidal AF, Wolcott ML, Wolf BR, Wright RW (2018) Ten-year outcomes and risk factors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a MOON longitudinal prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med 46:815–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517749850

Nordström A, Nordström P, Ekstrand J (2014) Sports-related concussion increases the risk of subsequent injury by about 50% in elite male football players. Br J Sports Med 48:1447–1450. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093406

Roi GS, Nanni G, Tencone F (2006) Time to return to professional soccer matches after ACL reconstruction. Sport Sci Health 1:142–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-006-0025-8

Tassignon B, Verschueren J, Delahunt E, Smith M, Vicenzino B, Verhagen E, Meeusen R (2019) Criteria-based return to sport decision-making following lateral ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Sports Med 49:601–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01071-3

Tol JL, Hamilton B, Eirale C, Muxart P, Jacobsen P, Whiteley R (2014) At return to play following hamstring injury the majority of professional football players have residual isokinetic deficits. Br J Sports Med 48:1364–1369. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093016

Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H, Ekstrand J (2016) ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med 50:744–750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095952

Walden M, Hägglund M, Werner J, Ekstrand J (2011) The epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injury in football (soccer): a review of the literature from a gender-related perspective. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 19:3–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-010-1172-7

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krutsch, W., Memmel, C., Alt, V. et al. Timing return-to-competition: a prospective registration of 45 different types of severe injuries in Germany’s highest football league. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 142, 455–463 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-03854-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-021-03854-8