Abstract

Introduction

Pediatric surgeons have yet to reach a consensus whether a gastric sleeve pull-up or delayed primary anastomosis for the treatment of esophageal atresia (EA), especially of the long-gap type (LGEA) should be performed. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate clinical outcome, quality of life (QoL), and mental health of patients with EA and their parents.

Methods

Clinical outcomes of all children treated with EA from 2007 to 2021 were collected and parents of affected children were asked to participate in questionnaires regarding their Quality of Life (QoL) and their child’s Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), as well as mental health.

Results

A total of 98 EA patients were included in the study. For analysis, the cohort was divided into two groups: (1) primary versus (2) secondary anastomosis, while the secondary anastomosis group was subdivided into (a) delayed primary anastomosis and (b) gastric sleeve pull-up and compared with each other. When comparing the secondary anastomosis group, significant differences were found between the delayed primary anastomosis and gastric sleeve pull-up group; the duration of anesthesia during anastomosis surgery (478.54 vs 328.82 min, p < 0.001), endoscopic dilatation rate (100% vs 69%, p = 0.03), cumulative time spent in intensive care (42.31 vs 94.75 days, p = 0.03) and the mortality rate (0% vs 31%, p = 0.03). HRQoL and mental health did not differ between any of the groups.

Conclusion

Delayed primary anastomosis or gastric sleeve pull-up appear to be similar in patients with long-gap esophageal atresia in many key aspects like leakage rate, strictures, re-fistula, tracheomalacia, recurrent infections, thrive or reflux. Moreover, HrQoL was comparable in patients with (a) gastric sleeve pull-up and (b) delayed primary anastomosis. Future studies should focus on the long-term results of either preservation or replacement of the esophagus in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Esophageal Atresia (EA) is a rare congenital malformation occurring in every 3–4 per 10.000 births [1]. In Germany less than 170 children undergo EA repair each year [2]. In particular, long-gap EA (LGEA), a form of EA with a large distance between the atretic ends, remains a rare and challenging condition for pediatric surgeons to treat.

While survival has dramatically improved over the last several decades, morbidity remains high [3,4,5]. Although no real consensus on the definition of LGEA exists, it is agreed upon that most LGEA cases cannot be corrected using a primary anastomosis of the esophageal ends [4]. In these cases, a secondary anastomosis surgical approach is required, which either involves (a) a delayed repair (delayed primary anastomosis) or (b) replacement (i.e., gastric pull-up or intestinal interposition) [6].

Proponents of the first method described above, namely repair, postulate that the native esophagus is the optimal conduit for EA repair and consequently esophageal preservation should be the primary goal of surgical management [4, 6]. As such, various techniques have been described involving primary anastomosis: elongation of the esophagus via (1) extrathoracically (Kimura technique), (2) external (Foker technique), or (3) internal traction sutures (Patkowski technique) [7, 8]. Even though replacement and preservation co-exist, experts have not been able to determine whether a delayed primary anastomosis, following traction of the esophagus, is superior to a replacement involving gastric, small intestinal or colonic interposition [9, 10]. As such, although there is a growing body of research on the long-term outcomes of individuals affected by EA, data comparing delayed primary anastomosis and gastric sleeve pull-up have been missing.

To assess which surgical method might be superior and to find consensus amongst experts, post-operative complications such as stricture rate, weight gain and the presence of reflux or dysphagia should be taken into account in the assessment of patient outcome, as recent studies have found conflicting results. Hannon et al. showed that children with gastric sleeve pull-up had significantly lower weight, higher need for supplementary feeding (19 vs. 0%), and dumping symptoms (25 vs. 0%) in adulthood [11], while other authors stated no significant differences in complications, length of hospital stay, or weight gain when comparing both techniques in long-gap EA patients [10].

However, as shown in current studies involving other congenital malformations, it is not sufficient to only assess clinical outcomes, such as the number and severity of complications, but one should also consider the subjective health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of the child and Quality of Life (QoL) of its parents, to determine whether one particular procedure is ‘superior’ [12] Mental health, can be defined as the “flexibility and ability to cope with adverse life events and function in social roles” [13], whereas QoL can be described as “the individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [14]. Recent reports suggest that mental health and HRQoL is only partially affected in children and adolescent with EA patients. More precise, EA patient seem to have emotional and behavioral problems when compared to the normative population [15,16,17,18]. No differences in the child’s HRQoL, between short and long gaps, have been reported [11, 19, 20]. However, families of children with EA seem to be burdened and recent studies reported a significantly reduced (Hr)QoL for these families [21, 22].

Knowledge of outcomes in the two popular secondary anastomoses techniques, namely (a) delayed primary repair and (b) gastric sleeve pull-up, focusing on patient’s clinical outcome and psychosocial condition (HrQoL and mental health) is needed. Thus, the aim of this study was to compare clinical outcomes, HRQoL, and mental health of children with esophageal atresia who underwent gastric sleeve pull-up to those who underwent delayed primary anastomosis surgery. In addition, following research questions were addressed: Do significant differences exists (1) in the distribution of clinical variables, HRQoL, and mental health between the primary anastomosis cohort and secondary anastomosis cohort, (2) in the distribution of HRQoL and mental health of the parents of affected children, and (3) in the distribution of HRQoL and mental health between affected patients and norm data?

Methods

Study design

The study included all children who underwent surgery for EA repair at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf between April 2007 and April 2021. The follow-up was based on the protocol of the Esophageal Atresia and Tracheo-Esophageal Fistula Support Federation (KEKS). This includes follow-up visits at the age of 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 4 years, 6 years, 10 years, 14 years and at age 18. Weight, food intake and reflux symptoms are checked at every visit. Clinical features are reevaluated until adulthood. Patients with missing data, such as long-term follow ups or those who refused to participate in the study, were excluded. The study received ethical approval from the Medical Chamber Hamburg (PV7161) and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04382820). Analysis and reporting were guided by Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations [23]. The patients were grouped into two main cohorts: (1) primary and (2) secondary anastomosis, while the secondary anastomosis group comprised the subgroups (a) gastric sleeve pull-up and (b) delayed primary anastomosis, which are the two main operating techniques performed for LGEA at our medical center.

Clinical variables

Patient data were collected using medical records and included clinical variables such as details regarding perinatal data, birth weight/length, and co-morbidities (i.e., VACTERL). The type and length of esophageal gap were identified by review of initial postnatal chest X-rays: The type of EA was defined according to VOGT criteria. Additionally, LGEA was defined as a gap between the proximal and distal esophageal ends measuring ≥ 3 vertebrae.

Moreover, age and weight at the time of EA corrective surgery, as well as the duration and type of surgery were analyzed. Post-operative data obtained for the study included duration of mechanical ventilation, chest tube, and length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU). Common complications, both long and short term (dysphagia, reflux, tracheomalacia, strictures, leakage, PPI requirements), were noted. Further, details regarding the number and duration of hospitalizations pertaining to dilatation procedures were recorded.

With respect to weight gain data, feeding regimes before and after anastomosis were analyzed and the functional oral intake scale (FOIS) was used to evaluate oral intake. FOIS consists of a numeric scale quantifying oral intake, ranging from 1 (nothing by mouth) to 7 (full oral diet, no restrictions) [24]. Weight and height measurements were collected and converted into the weight-for-length z-score using The Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) growth standards [25]. To assess the presence of reflux symptoms, guardians were sent the ‘GERD-Q’; a questionnaire containing 7 items related to the frequency and severity of symptoms related to reflux disease [26, 27].

Psychosocial outcomes

A study-specific questionnaire was sent to the families of affected children to assess the psychosocial outcomes like their (Hr)QoL and mental health status. Sociodemographic variables included sex, age, level of care required for the affected child, marital status, number of children, educational qualifications, employment status, and current physical/mental health status.

Parental quality of life (QoL)

Parental QoL was measured using the Ulm Quality of Life Inventory for Parents (ULQIE), which is designed for parents of chronically ill children [28]. The ULQIE consists of 29 items, which are rated on a five-point rating scale. Five respective subscales measure (1) physical and daily functioning, (2) satisfaction with the family, (3) emotional distress, (4) self-development, and (5) well-being. Solely, the total scale by averaging all score was used in this study, illustrating overall QoL. Lower scores indicate decreased QoL. The ULQIE has been shown to provide reliable psychometric properties and normative data for parents of chronically ill children suffering from various diseases [28].

Parental mental health

The parent’s mental health was measured with the self-report questionnaire Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [29]. The BSI consists of 53 items, measuring nine subscales including (1) somatization, (2) compulsivity, (3) interpersonal sensitivity, (4) depression, (5) anxiety, (6) hostility, (7) phobic fear, (8) paranoid thinking, and (9) psychoticism, and three global indices, including the Positive Symptom Distress Index, Positive Symptom Total, and Global Severity Index (GSI). In this study, solely the GSI was used to provide a composite score of overall distress by using the mean of all items. Lower scores indicate decreased mental health. The German version of the BSI has been found to assess psychometric properties of individuals in a reliable and valid fashion [29].

Children’s health-related quality of life

The children’s HRQoL using the parent-report version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory—Short Form 15 (PedsQL TM 4.0 SF-15) [30]. The instrument consists of 15 items, measuring four subscales including (1) physical functioning, (2) emotional functioning, (3) social functioning, and (4) school functioning. Additionally, a total score can be calculated. Raw scores were converted into a standardized 0–100 scale according to the manual. In this study, solely the total score was used, with higher scores representing greater overall HRQoL. The German version of the PedsQL has shown adequate psychometric properties [31].

Children’s mental health

Children’s mental health was assessed using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [32]. The SDQ consists of 25 items, which are rated on a three-point rating scale. The instrument comprises five subscales of 5 items each including (1) emotional symptoms, (2) conduct problems, (3) hyperactivity, (4) peer problems, (5) prosocial behavior, and a total difficulties score. Solely the total difficulties score was used, by summing scores from all scale, except the prosocial scale. The SDQ has been shown to assess emotional and behavioral status, as well as prosocial behavior [32].

Statistics

For descriptive data, frequencies, means, standard deviations, and bivariate tests (Chi-square tests) were used. Differences between groups were calculated using t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank test. Pearson correlations was applied to investigate the bivariate associations between psychosocial outcomes. To account for any known biases, propensity score matching was performed using an optimal matching algorithm with a caliper of 0.2 for gender, age, weight at operation, diagnosis, and revisionary surgery. Multiple linear regression models were used to define predictors of psychosocial outcomes. To indicate the size of the effect, Cohen’s d and Cramer’s V were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p \(\le\) 0.05 (two-tailed). Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 28 and GraphPad Prism 9.

Results

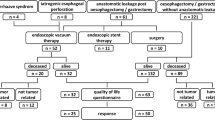

In total, 104 children with EA were identified, of which 6 were excluded based on the previously stated exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Overall, 61 patients underwent primary anastomosis for corrective surgery of EA, while 37 patients underwent a secondary anastomosis surgery. Out of the secondary anastomosis procedure, 24 patients were treated using the delayed primary anastomosis, which involved placement of internal traction sutures at the time of fistula ligation and a gastrostomy for feeding. The remaining 13 patients in the secondary anastomosis group received a gastric sleeve pull-up operation. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the CONSORT flow diagram illustrating the total patient cohort and subgroups for analysis of clinical outcomes.

Clinical features of primary vs. secondary anastomosis

Clinical outcomes of patients who underwent a primary anastomosis surgery were compared to those who underwent a secondary anastomosis surgery for EA. As suspected and shown in Table 1, children with primary anastomosis were significantly older, heavier, and had significantly shorter gap length than patients who underwent secondary repair. As shown in Table 2, primary anastomosis patients experienced significantly shorter operating and anesthesia times, during both the anastomosis repair surgery as well as all subsequent surgeries associated with the EA. However, the length of post-operative stay in the ICU and mechanical ventilation did not differ significantly between the primary and secondary anastomosis groups. Further, children with primary anastomoses had significantly fewer complications like tracheomalacia and reflux symptoms and were quicker to reach full oral feedings. Compared to patients who underwent secondary anastomosis, a primary anastomosis seems to lead to a fewer number of required endoscopic dilation procedures at the esophageal stricture site. Consequently, this results in a shorter cumulative duration of general anesthesia, operating time, and stay in the ICU.

Clinical outcome of delayed anastomosis vs. gastric pull-up

As presented in Table 3, there were no significant differences regarding gap length between the secondary anastomosis subgroups. Additionally, as patients were propensity score matched for gender, age, and weight at the time of surgery, there were no significant differences with regards to these factors (Table 4). As summarized in Table 4, there were no differences regarding clinical outcomes and long-term complications between the two secondary anastomosis subgroups. However, the duration of general anesthesia during the surgery was significantly higher in the gastric sleeve pull-up group than the delayed anastomosis group. When analyzing all atresia-related surgeries and hospitalizations, no significant differences in the cumulative duration of general anesthesia or operating time between these two groups were found. Additionally, there were no significant differences regarding the of number of days spent in ICU or the duration of machine ventilation time post-operatively. Even more, the rates of post-operative complications, such as anastomosis leakage, strictures, re-fistula, tracheomalacia, scoliosis, recurrent infections or reflux (i.e., functional oral intake scale) were similar across both groups. The cumulative number of days spent in the ICU immediately following anastomosis surgery and all stays related to the atresia diagnosis thereafter was referred to as ‘cumulative length of stay in the ICU’, which was significantly higher in the delayed primary anastomosis group. The overall mortality rate was significantly lower in the gastric sleeve pull-up group. However, bearing in mind that patients in the gastric sleeve pull-up group were less frequent pre-term and had a lower rate of cardiac and anorectal malformations could potentially be accounting for this significant difference in mortality. As shown in Fig. 1, there were no long-term significant differences in weight gain between the gastric sleeve pull-up and delayed primary anastomosis group.

(Health-related) Quality of life and mental health

Out of 104 families assessed for eligibility and 63 families who received the questionnaires, in total 39 families responded and were included in analysis of the questionnaires. Thus, responder rate was almost comparable to previous studies [16, 17]. There were no significant differences between respondents and non-respondents regarding weight, age, gender, gap length, associated co-morbidities, operation method and complications. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the CONSORT flow diagram illustrating the total patient cohort for analysis of HRQoL and mental health questionnaires. Table 5 shows the sociodemographic and disease characteristics of the participating parents and their affected child. When comparing primary with secondary anastomosis, as well as delayed primary anastomosis with gastric sleeve pull-up, there were no significant differences. Neither the QoL and mental health of the patient’s parents, nor the parent-reported HRQoL and mental health of the affected child, showed any significant differences in the comparison of these groups. Additionally, the entire cohort was analyzed in comparison to norm data available for each of the standardized questionnaires. Here, mothers reported a significant reduction in their child’s HRQoL and mental health, while fathers only reported a significant reduction in their child’s mental health. Data is summarized in Table 6.

Discussion

The debate amongst pediatric surgeons whether to preserve or replace the esophagus in LGEA patients has been ongoing for decades [9, 10]. Proponents of a delayed anastomosis procedure often state that spontaneous growth between the atretic ends of the esophagus can occur in children with EA within the first months of their lives. Therefore, waiting a specific time before performing corrective EA surgery is favored. Indeed, three months after birth the newborn’s esophagus is much thicker and more resilient than directly after birth [33]. To accelerate this process, some surgeons advocate elongation of the esophagus under traction (Foker technique) [34]. This technique has, however, been associated with a high rate of esophageal strictures and stump tears [35]. On the other hand, proponents of the primary gastric sleeve pull-up argue that preservation is only useful if the preserved esophagus is functioning properly, which may only be true for “shorter” long gaps [36]. However, the primary gastric sleeve pull-up procedure is irreversible and disrupts gastrointestinal physiology. As such, malignancy rates associated with chronic reflux need to be considered as a long-term complication. Chronic GERD after EA can lead to mucosal damage, esophageal structuring, Barrett’s esophagus, and eventually esophageal adenocarcinoma. Higher incidences of these complications have been reported in adults after EA repair, regardless of the technique [37, 38].

The current study suggests that the outcome after gastric sleeve pull-up (replacement) and delayed primary anastomosis (preservation) in LGEA patients is comparable in many aspects. This was observed regarding anastomosis leakage, stricture rate, reflux, dysphagia, and cumulative operating time. Yet significant differences were found in the cumulative duration of stays in the ICU as well as mortality which may be heavy affected by associated malformations. However, HrQoL and mental health of the patients as well as their parents were found to be similar in both subgroups.

With respect to clinical outcomes, our patient cohort showed a high rate of dysphagia and reflux in both secondary anastomosis subgroups. However, this outcome is not uncommon and has been reported as a common long-term complication following repair surgery in LGEA patients [39]. Yet, when examining dysphagia and reflux amongst patients who underwent the primary as well as secondary anastomosis approach in our study, our findings were able to confirm those of a recent study. This study revealed that patients who underwent early definitive repair of the esophagus reported significantly lower incidences of oro-pharyngeal dysphagia [40].

With respect to the HRQoL, digestive issues, such as the ones mentioned above, have been shown to significantly impact patients and their family’s HRQoL [41,42,43]. On the bright side however, studies have reported that adults who underwent EA surgery as children do not report a lower HRQoL because of this reflux or dysphagia [44, 45]. The current study, however, showed a significant reduction in parent-reported HRQoL and mental health of patients with EA when compared to norm values, which is in line with a recent report [46]. When examining the different EA treatment approaches, no significant differences in the parent-reported HRQoL or mental health of the children were found, while parents themselves, also reported no significant differences in their own HRQoL or mental health. One explanation for these contradictory findings can possibly be explained by the fact that in our study parents filled out the forms on behalf of their respective child and the patients themselves were not asked to participate. This might skew the actual HRQoL of the individuals treated for EA, as it has been described that proxies may report the HRQoL poorer than EA patients themselves [47].

Summing up, when considering which surgical procedure to perform in order to treat LGEA, every surgeon should not only weigh the risks of the surgery, but also the risks not directly associated with the actual surgical procedure. As an example, it has been proposed that the newborn stage coincides with a time frame of rapid brain development. During this time, surgery performed with concomitant anesthesia may disrupt very important stages of development. It has been reported that complex surgeries and long anesthesia may lead to neurodevelopmental delays in cognition, learning, and behavior [48]. Recently, long-term neurodevelopment impairment in children with EA have been found; especially in motor function and in cognitive performance [49].

Consequently, multiple interventions, with or without general anesthesia, ought to be avoided in the neonatal period and should be considered when developing a treatment plan for a patient with LGEA. A single rather than multiple operations positively affect HRQoL [50]. As such, factors such as HRQoL and mental health should be considered key essentials in determining which surgical technique is ‘superior’.

Limitations

Most limitations of the current study are inherent with the retrospective cross-sectional study design, in particular the small numbers and the lack of randomization. Thus, propensity score matching was used to limit the effects of the most relevant factors [51]. Moreover, due to the cross-sectional nature of the design, the statements regarding the treatment evaluation can only be made cautiously. The rate of non-respondents for the HRQoL and mental health assessment is unfortunately frequent and therefore may affect the results [52]. Even though a condition-specific questionnaire is recommended in addition to the use of a general questionnaire for HRQoL in previous research as a condition-specific questionnaire is generally more sensitive to evaluate clinical differences [53,54,55,56], we did not use it due to the total amount of questionnaires used in the research project, which should be considered as a limitation of our study. Nonetheless, validated standardized instruments were used, which is a strength of the study. Moreover, GERD-Q is often used but has not been validated for children. Thus, reflux may be either over- or underestimated in the current study. Finally, in this study, parent-proxy instead of child-report has been used which may over- or under-estimate certain aspects.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the current study, patients with gastric sleeve pull-up procedure have similar clinical outcomes, generic HRQoL and mental health when compared to delayed primary anastomosis. However, the long-term results of either preservation or replacement of the esophagus remain uncertain, particularly regarding chronic reflux-associated metaplasia resulting in esophageal adenocarcinoma, neurodevelopmental impact of multiple surgeries, condition-specific QoL and needs of follow-up care. Future studies should focus on these aspects.

Data availability

All data is avaiable upon request of the corresponding author.

References

Nassar N, Leoncini E, Amar E et al (2012) Prevalence of esophageal atresia among 18 international birth defects surveillance programs. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 94:893–899. https://doi.org/10.1002/BDRA.23067

Elrod J, Boettcher M, Mohr C, Reinshagen K (2021) An analysis of the care structure for congenital malformations in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int 118:601–602. https://doi.org/10.3238/ARZTEBL.M2021.0213

Stadil T, Koivusalo A, Svensson JF et al (2019) Surgical treatment and major complications within the first year of life in newborns with long-gap esophageal atresia gross type A and B—a systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 54:2242–2249. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2019.06.017

Baird R, Lal DR, Ricca RL et al (2019) Management of long gap esophageal atresia: a systematic review and evidence-based guidelines from the APSA Outcomes and Evidence Based Practice Committee. J Pediatr Surg 54:675–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2018.12.019

Tan Tanny SP, Comella A, Hutson JM et al (2019) Quality of life assessment in esophageal atresia patients: a systematic review focusing on long-gap esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 54:2473–2478. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2019.08.040

Shieh HF, Jennings RW (2017) Long-gap esophageal atresia. Semin Pediatr Surg 26:72–77. https://doi.org/10.1053/J.SEMPEDSURG.2017.02.009

Subramaniam T, Martin BP, Jester I et al (2022) A single centre experience using internal traction sutures in managing long gap oesophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 57:516. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2022.05.008

Patkowski D (2021) Thoracoscopic technique using internal traction sutures for long-gap esophageal atresia repair. In: Lacher M, Muensterer OJ (eds) Video atlas of pediatric endosurgery (VAPE). Springer, Cham, pp 219–222

Lee HQ, Hawley A, Doak J et al (2014) Long-gap oesophageal atresia: comparison of delayed primary anastomosis and oesophageal replacement with gastric tube. J Pediatr Surg 49:1762–1766. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2014.09.017

Jensen AR, McDuffie LA, Groh EM, Rescorla FJ (2020) Outcomes for correction of long-gap esophageal atresia: a 22-year experience. J Surg Res 251:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JSS.2020.01.020

Hannon E, Eaton S, Curry JI et al (2020) Outcomes in adulthood of gastric transposition for complex and long gap esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 55:639–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2019.08.012

Ebrahim S (1995) Clinical and public health perspectives and applications of health-related quality of life measurement. Soc Sci Med 41:1383–1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00116-O

Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M et al (2015) Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry 14:231–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20231

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Group (1995) The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 41:1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K

Witt S, Dingemann J, Dellenmark-Blom M, Quitmann J (2021) Parent–child assessment of strengths and difficulties of german children and adolescents born with esophageal atresia. Front Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPED.2021.723410/PDF

Mikkelsen A, Boye B, Diseth TH et al (2022) Traumatic stress, mental health, and quality of life in adolescents with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 57:1423–1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2020.10.029

Dellenmark-Blom M, Ax SÖ, Lilja HE et al (2022) Prevalence of mental health problems, associated factors, and health-related quality of life in children with long-gap esophageal atresia in Sweden. J Pediatr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2022.12.004

Dellenmark-Blom M, ÖrnöAx S, Öst E et al (2022) Postoperative morbidity and health-related quality of life in children with delayed reconstruction of esophageal atresia: a nationwide Swedish study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13023-022-02381-Y

Gallo G, van Tuyll van Serooskerken ES, Tytgat SHAJ et al (2021) Quality of life after esophageal replacement in children. J Pediatr Surg 56:239–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDSURG.2020.07.014

Youn JK, Park T, Kim SH et al (2018) Prospective evaluation of clinical outcomes and quality of life after gastric tube interposition as esophageal reconstruction in children. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013801

Witt S, Dellenmark-Blom M, Dingemann J et al (2019) Quality of life in parents of children born with esophageal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg 29:371–377. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0038-1660867

Tan Tanny SP, Trajanovska M, Muscara F et al (2021) Quality of life outcomes in primary caregivers of children with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr 238:80-86.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JPEDS.2021.07.055

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG et al (2007) Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 18:805–835. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0B013E3181577511

Crary MA, Carnaby Mann GD, Groher ME (2005) Initial psychometric assessment of a functional oral intake scale for dysphagia in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 86:1516–1520. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APMR.2004.11.049

IJsselstijn H, Gischler SJ, Toussaint L et al (2016) Growth and development after oesophageal atresia surgery: need for long-term multidisciplinary follow-up. Paediatr Respir Rev 19:34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PRRV.2015.07.003

Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Hoff DAL, Hatlebakk JG (2013) Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 37:564–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/APT.12204

Jones R, Junghard O, Dent J et al (2009) Development of the GerdQ, a tool for the diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 30:1030–1038. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1365-2036.2009.04142.X

Goldbeck L, Storck M (2002) Das Ulmer Lebensqualitäts-Inventar für Eltern chronisch kranker Kinder (ULQIE). Z Klin Psychol Psychother 31:31–39. https://doi.org/10.1026//1616-3443.31.1.31

Geisheim C, Hahlweg K, Fiegenbaum W et al (2002) Das brief symptom inventory (BSI) als Instrument zur Qualitätssicherung in der Psychotherapie. Diagnostica 48:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1026//0012-1924.48.1.28

Chan KS, Mangione-Smith R, Burwinkle TM et al (2005) The PedsQL: reliability and validity of the short-form generic core scales and asthma module. Med Care 43:256–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200503000-00008

Felder-Puig R, Frey E, Proksch K et al (2004) Validation of the German version of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) in childhood cancer patients off treatment and children with epilepsy. Qual Life Res 13:223–234. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000015305.44181.E3

Klasen H, Woerner W, Rothenberger A, Goodman R (2003) Die deutsche Fassung des Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Deu)-Übersicht und Bewertung erster Validierungs-und Normierungsbefunde. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 52:491–502. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11780/2700

Oliver DH, Martin S, Belkis DMI et al (2021) Favorable outcome of electively delayed elongation procedure in long-gap esophageal atresia. Front Surg. https://doi.org/10.3389/FSURG.2021.701609

Krishnan U, Singh H, Kaakoush N et al (2019) DOZ047.19: outcomes in the management of long-gap esophageal atresia: is the Foker technique superior? Diseases Esophagus. https://doi.org/10.1093/DOTE/DOZ047.19

Nasr A, Langer J (2013) Mechanical traction techniques for long-gap esophageal atresia: a critical appraisal. Eur J Pediatr Surg 23:191–197. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0033-1347916

Zeng Z, Liu F, Ma J et al (2017) Outcomes of primary gastric transposition for long-gap esophageal atresia in neonates. Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007366

Taylor ACF, Breen KJ, Auldist A et al (2007) Gastroesophageal reflux and related pathology in adults who were born with esophageal atresia: a long-term follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 5:702–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CGH.2007.03.012

Sistonen SJ, Koivusalo A, Nieminen U et al (2010) Esophageal morbidity and function in adults with repaired esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula: a population-based long-term follow-up. Ann Surg 251:1167–1173. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0B013E3181C9B613

Hölscher AC, Laschat M, Choinitzki V et al (2017) Quality of life after surgical treatment for esophageal atresia: long-term outcome of 154 patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg 27:443–448. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0036-1597956

Soyer T, Arslan SS, Boybeyi Ö et al (2022) The role of oral feeding time and sham feeding on oropharyngeal swallowing functions in children with esophageal atresia. Dysphagia. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-022-10461-1

Dellenmark-Blom M, Quitmann J, Dingemann J et al (2020) Clinical Factors Affecting Condition-Specific Quality-of-Life Domains in Pediatric Patients after Repair of Esophageal Atresia: The Swedish-German EA-QOL Study. Eur J Pediatr Surg 30:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0039-1693729

di Natale A, Brestel J, Mauracher AA et al (2022) Long-term outcomes and health-related quality of life in a Swiss patient group with esophageal atresia. Eur J Pediatr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0041-1731391

Rozensztrauch A, Śmigiel R, Błoch M, Patkowski D (2020) The impact of congenital esophageal atresia on the family functioning. J Pediatr Nurs 50:e85–e90. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PEDN.2019.04.009

Tannuri U, Tannuri ACA, Gonçalves MEP, Cardoso SR (2008) Total gastric transposition is better than partial gastric tube esophagoplasty for esophageal replacement in children. Dis Esophagus 21:73–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1442-2050.2007.00737.X

Deurloo JA, Ekkelkamp S, Hartman EE et al (2005) Quality of life in adult survivors of correction of esophageal atresia. Arch Surg 140:976–980. https://doi.org/10.1001/ARCHSURG.140.10.976

Dellenmark-Blom M, Ax SÖ, Lilja HE et al (2023) Prevalence of mental health problems, associated factors, and health-related quality of life in children with long-gap esophageal atresia in Sweden. J Pediatr Surg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.12.004

Witt S, Bloemeke J, Bullinger M et al (2019) Agreement between mothers’, fathers’, and children’s’ ratings on health-related quality of life in children born with esophageal atresia—a German cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12887-019-1701-6

Keunen K, Sperna Weiland NH, de Bakker BS et al (2022) Impact of surgery and anesthesia during early brain development: a perfect storm. Paediatr Anaesth 32:697. https://doi.org/10.1111/PAN.14433

van Hoorn CE, ten Kate CA, Rietman AB et al (2021) Long-term neurodevelopment in children born with esophageal atresia: a systematic review. Dis Esophagus. https://doi.org/10.1093/DOTE/DOAB054

Ludman L, Spitz L (2003) Quality of life after gastric transposition for oesophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg 38:53–57. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpsu.2003.50009

Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ (2015) The propensity score. JAMA 314:1637–1638. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2015.13480

Coste J, Quinquis L, Audureau E, Pouchot J (2013) Non response, incomplete and inconsistent responses to self-administered health-related quality of life measures in the general population: patterns, determinants and impact on the validity of estimates—a population-based study in France using the MOS SF-36. Health Qual Life Outcomes 11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-44/TABLES/4

Dellenmark-Blom M, Chaplin JE, Gatzinsky V et al (2016) Health-related quality of life experiences among children and adolescents born with esophageal atresia: development of a condition-specific questionnaire for pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg 51:563–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.09.023

Dellenmark-Blom M, Dingemann J, Witt S et al (2018) The esophageal-atresia-quality-of-life questionnaires: feasibility, validity and reliability in Sweden and Germany. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 67:469–477. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000002019

ten Kate CA, Rietman AB, Kamphuis LS et al (2021) Patient-driven healthcare recommendations for adults with esophageal atresia and their families. J Pediatr Surg 56:1932–1939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.12.024

TenKate CA, Group on behalf of the DS, Teunissen NM et al (2022) Development and validation of a condition-specific quality of life instrument for adults with esophageal atresia: the SQEA questionnaire. Diseases Esophagus. https://doi.org/10.1093/DOTE/DOAC088

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., M.F., collected all data, M.H., M.F., J.E., D.V., J.B., M.B. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures 1-3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

383_2023_5448_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary file 1 CONSORT Flow Diagram illustrating the total patient cohort and subgroups for analysis of clinical outcomes.

383_2023_5448_MOESM2_ESM.docx

Supplementary file 2 CONSORT Flow Diagram illustrating the total patient cohort for analysis of HRQoL and mental health questionnaires.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boettcher, M., Hauck, M., Fuerboeter, M. et al. Clinical outcome, quality of life, and mental health in long-gap esophageal atresia: comparison of gastric sleeve pull-up and delayed primary anastomosis. Pediatr Surg Int 39, 166 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-023-05448-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-023-05448-4