Abstract

Feedback between the Mediterranean Sea and the atmosphere on various temporal and spatial scales plays a major role in the regional climate system. We studied the impact of horizontal atmospheric grid resolution (grid-spacing of ~9 vs. ~50 km) and dynamic ocean coupling (the ocean model NEMOMED12) in simulations with the regional climate model COSMO-CLM. The evaluation focused on sea surface heat fluxes, 10-m wind speed, and sea surface temperature (SST) parameters on both seasonal and annual timescales. The finer grid improved the wind speed (particularly near coastal areas) and subsequently the turbulent heat flux simulations. Both parameters were better simulated with the interactive ocean model NEMOMED12 than with prescribed daily ocean SSTs (using near-observation ERA-Interim reanalysis based SSTs), but coupling introduced a warm SST bias in winter. Radiation fluxes were slightly better represented in coarse-grid simulations. Still, only the higher-resolution coupled simulations could reproduce the observed net outgoing total heat flux over the Mediterranean Sea. Investigation of the impact of sub-diurnal SST variations showed a strong effect on sub-daily heat fluxes and wind speed but minor effects at longer time scales. Therefore, a coupled atmosphere–ocean climate model should be preferred for studying the Mediterranean Sea climate system. Higher-resolution models should be preferred, but they are not yet able to perform better than their coarse-resolution predecessors in all aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

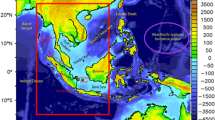

The semi-enclosed Mediterranean Sea, with its intricate coastline and topographic features, functions as a source of moisture and heat and has a substantial impact on local and remote climate conditions (Artale et al. 2010). A wide range of oceanic processes and air-sea interactions of global and regional interest occur in the Mediterranean basin. The Mediterranean climate is known for its large seasonal temperature variations, strong winds (e.g., Mistral, Tramontane, and Bora winds), heavy precipitation, and cyclones (e.g., Medicanes). This region is also known as a “hot spot” in future climate change projections because of a substantial decrease in mean precipitation and increase in precipitation variability during warm and dry seasons (Giorgi 2006). The formation of intermediate and deep-water masses in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea is of fundamental importance for regional and global meridional overturning circulations (Calmanti et al. 2006; Josey 2003). Net sea surface heat flux (NH) anomalies play a significant role in the local climate (Roether et al. 2005; Theocharis et al. 1999). Therefore, an accurate representation of the ocean and atmosphere, especially the air-sea interactions, is crucial for accurate modeling of the Mediterranean climate. The NH is defined as:

where SW and LW are short-wave and long-wave radiation, respectively, and LH and SH are latent and sensible heat flux, respectively.

In general, coarse-resolution global models cannot sufficiently resolve the local and mesoscale processes that characterize the Mediterranean region. Therefore, these global models cannot correctly describe air-sea exchanges and their variability (Elguindi et al. 2009). On the other hand, high-resolution global models for studying regional processes are not yet feasible from a computational standpoint. This issue can be resolved by downscaling using uncoupled regional climate models (RCMs), which can have grid spacing finer than 50 km with a more realistic representation of regional features (see for example, Gao et al. 2006; Herrmann and Somot 2008; Elguindi et al. 2009). The relatively high resolution of RCMs directly impacts the air-sea exchange and improves the representation of temperature, wind, humidity, and the exchange of other hydrological parameters (e.g., Ruti et al. 2008 ; Ruiz et al. 2008; Herrmann and Somot 2008; Dell’Aquila et al. 2012; Obermann et al. 2016).

However, the high-resolution and high-frequency interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere are missing in RCMs, which results in large uncertainties in air-sea fluxes (Dell’Aquila et al. 2012; Herrmann and Somot 2008; Herrmann et al. 2011). An RCM’s sea-surface temperature (SST) is provided via reanalysis (e.g., ERA-Interim and NCEP/NCAR) or from Atmosphere–Ocean Coupled General Circulation Model (AOGCM) simulations. The spatial and temporal quality of the SSTs in these datasets is too coarse to resolve eddies (the internal Rossby radius of deformation is of the order of 15 km) and other high-frequency variations that characterize the Mediterranean Sea. Another important feature of the SST is its diurnal variation, which is missing or not well represented in the reanalysis and the majority of the AOGCM datasets as a result of coarse spatial and temporal resolution (e.g., ERA-Interim has daily values over the ocean). The SST diurnal variations affect the atmospheric conditions and in turn exert feedback on the SST. They can increase surface heat fluxes by roughly 10 Wm−2 (Fairall et al. 1996), which can influence the atmospheric variability on sub-daily to intra-seasonal time scales (e.g., Kawai and Wada 2007). In general, SST diurnal variations are small but have important effects on the physical and biological processes in seas and oceans (Kawai and Wada 2007). Therefore, an atmosphere–ocean regional coupled climate model (AORCM) with high-resolution and high-frequency (e.g., hourly) air-sea exchanges appears to be important for a good representation of Mediterranean climate characteristics.

Several modeling studies have investigated the impact of atmosphere–ocean coupling over the Mediterranean Sea. These studies have shown that two-way, high-frequency interactions and higher SST spatial resolution improve the representation of surface heat fluxes, hydrological parameters, winds, and extremes events (e.g., cyclogenesis, medicanes, and heavy precipitation events) in the Mediterranean region (Lebeaupin Brossier and Drobinski 2009; Sanna et al. 2013; Lebeaupin Brossier et al. 2014; Akhtar et al. 2014). In a recent study, Panthou et al. (2016) show that high-resolution regional atmospheric models coupled with Mediterranean Sea models improve the representation of hot days and droughts more than heavy precipitation events. Somot et al. (2008) show that a high-resolution AORCM amplifies the climate change signal compared to an RCM in future projections in the Euro-Mediterranean region. They explained this result based on better consistency among the SST, air-sea fluxes, and vertical structure of the atmosphere in the AORCM. Artale et al. (2010) show that high-resolution AORCMs can yield a more reliable estimate of air-sea fluxes than RCMs because of better SST simulations and wind fields. In another study, Sevault et al. (2014) show that ocean coupling improved the NH, but large errors occurred in individual components (particularly in latent heat flux and long wave radiation). Dubois et al. (2012) used an ensemble of five AORCMs and showed that the basin-wide average of the NH components differed significantly between the ensemble members.

All the studies noted above used an atmospheric grid resolution in the range of 20–50 km to investigate the added value of ocean coupling over different timescales. These studies show that even though the AORCMs improved the representation of air-sea fluxes over the Mediterranean Sea, large uncertainties still persist.

In this study, we investigated the spatial patterns and basin-wide averages of all of the components of NH, 10-m wind speed, and SST on seasonal and annual timescales to address the following questions:

-

1.

Does ocean–atmosphere coupling improve the simulation of sea surface heat flux and 10-m wind speed over the Mediterranean Sea?

-

2.

Does horizontal atmospheric grid resolution affect the sea surface heat flux and 10-m wind speed over the Mediterranean Sea?

-

3.

Are certain areas and seasons more sensitive than others to the ocean coupling and atmospheric grid resolution?

-

4.

What is the impact of SST diurnal variation on air-sea fluxes of heat and wind speed on sub-daily and longer timescales?

The paper is organized as follow. Section 2 explains the modeling system and experimental setup of our simulations. The results are presented and discussed in Sect. 3. The paper concludes in Sect. 4 with a summary of results and prospective future research.

2 Modeling system and experiment setups

In this study, we employ the RCM COSMO-CLM v4.21 (CCLM), based on non-hydrostatic equations (Rockel et al. 2008) in uncoupled and coupled (atmosphere–ocean) configurations. For the coupled ocean–atmosphere model, CCLM is coupled to the regional ocean model NEMOMED12.

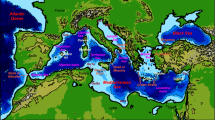

We used an atmospheric grid resolution of 0.44° (~50 km; 114 × 79 grid points and 32 σ levels) and a finer atmospheric grid resolution of 0.088° (~9 km; 596 × 386 grid points and 32 σ levels) in both the uncoupled and coupled configurations. The initial and boundary conditions for CCLM were taken from the ECWMF’s ERA-Interim reanalysis data (Dee et al. 2011), except the soil temperature and water content values for initialization. Here, the climatological values (2000–2010) of soil temperature and water content were taken from uncoupled CCLM simulations for a better soil initialization following the suggestion of Kothe et al. (2014). In the uncoupled configuration, SST is prescribed using the ERA-Interim’s daily SST. In the coupled configuration, SST is also prescribed from the ERA-Interim data except over the Mediterranean Sea, where it is calculated using the regional ocean model NEMOMED12. The aerosol optical depth data from MACC (Monitoring Atmospheric Composition and Climate), which is a global reanalysis product of the ECWMF (http://www.copernicus-atmosphere.eu), are used in CCLM. For both the uncoupled and coupled configurations, CCLM uses numerical time steps of 150 s and 40 s for the coarse and high-resolution simulations, respectively, with a third-order Runge–Kutta numerical integration scheme. In CCLM, we used the one-dimensional prognostic turbulent kinetic energy scheme for vertical turbulent diffusion parameterization and a delta-two-stream radiation scheme proposed by Ritter and Geleyn (1992). The simulation domain follows the Med-CORDEX requirements indicated in Fig. 1 of Ruti et al. (2015).

Mean differences in sea surface temperatures (in °C) for winter, spring, summer, and autumn (columns) in the period 2001–2003. The rows show the differences between CCLM08 and observations OISST, between CPL08 and observations OISST, between CPL08 and CCLM08, and CPL08 and CPL44, respectively. The numbers given in the panels are the total mean differences (MD) and the mean RMSEs as MD/RMSE

NEMOMED12 is a regional configuration of the ocean circulation model (OGCM) NEMO (Madec and the NEMO Team 2008) for the Mediterranean Sea (Lebeaupin Brossier et al. 2011, 2012). It has a horizontal resolution of 1/12° (~6.5–8.0 km in latitude and ~5.5–7.5 km in longitude; 567 × 264 grid points) and 50 vertical levels. The changes in horizontal grid resolution are due to the use of the standard three-polar ORCA grid of NEMO (Beuvier et al. 2012). The NEMOMED12 grid encompasses the entire Mediterranean Sea and a small part of the near Atlantic Ocean as a buffer zone; it does not include the Black Sea. The vertical levels were defined in z-coordinates using the partial step formulation. We adopted a numerical time step of 720 s in this configuration. NEMOMED12 was initialized using the MEDATLAS-II (Rixen 2012) monthly mean seasonal climatology (1945–2002) in the Mediterranean Sea and in the Atlantic buffer zone using the climatology of Levitus et al. (2005). To obtain an initial equilibrium state of the Mediterranean Sea, NEMOMED12 coupled with the coarse-grid CCLM was spun-up for 25 years. The ERA-Interim data (1979–1985) were used to drive the CCLM with a random-year strategy. To model the river discharge of fresh water into the Mediterranean Sea, the climatological average of the inter-annual data of Ludwig et al. (2009) was used to compute the monthly river discharge values (Beuvier et al. 2012). For a more detailed discussion of the NEMOMED12 configuration, we refer the reader to Beuvier et al. (2012).

The CCLM and NEMOMED12 models are coupled via OASIS3-MCT (Valcke 2013) with a 3-h coupling time step. The NEMOMED12 sends SST to CCLM through OASIS3-MCT and in turn receives solar energy, non-solar heat, momentum, and freshwater fluxes. OASIS3-MCT uses a bi-cubic scheme to interpolate the fields from one grid to another.

We conducted the coupled and uncoupled model evaluation runs for the periods of 1979–2011 and 2000–2003 with the coarse and fine atmospheric grids, respectively. The coarse-coupled simulations were initialized with the ocean spun-up state of 1979 (the first year is used as an adjustment period for the ocean and atmosphere). The sea state of 2000 from the coarse-coupled simulations was then used to initialize the high-resolution coupled simulations from 2000 to 2003; a 1 year spin-up was used to adjust to the high-resolution atmospheric forcing.

Additionally, we performed a sensitivity experiment to analyze the effects of coupling and SST diurnal variations of sea surface heat fluxes on seasonal and sub-daily timescales. Hence, we averaged the SST over the Mediterranean Sea calculated by NEMOMED12 in the high-resolution coupled simulations over periods of 5 days. These simulations were designed to include the same climatology and sub-monthly variations without the diurnal SST variations, short-term extreme variability and two-way active interaction of the Mediterranean Sea and the atmosphere. The temporally smoothed SSTs over the Mediterranean Sea combined with the ERA-Interim boundary conditions were then used to drive the high-resolution uncoupled CCLM simulations for the period of 2000–2003. This allowed for a fair investigation of SST diurnal variations and ocean coupling impacts.

Hereafter, we use the abbreviations “CPLxx” for the coupled simulations, “CCLMxx” for the uncoupled simulations, and CCLMxx_SSTavg for simulations with averaged SSTs, where “xx” refers to atmospheric grid resolution (i.e., “44” for 0.44° and “08” for 0.088°).

For the evaluation of the simulations, we used the following datasets:

-

The NOAA Daily Optimum Interpolation SST (OISST), available from 1981 to present. This dataset contains global ocean SST data at 6-h intervals on a 0.25° grid. Observations from different platforms (satellites, ships, and buoys) were used to construct the OISST dataset (Reynolds et al. 2007).

-

NOAA (SeaWinds), available from July 9, 1987 to present. This dataset contains global ocean 10-m winds and wind stresses at 6-h intervals on a 0.25° grid. Observations from multiple satellites were combined to generate the dataset (Zhang et al. 2006).

-

Objectively Analyzed Air-sea Fluxes (OAFlux). This dataset of sea surface fluxes of heat, SST, and 10-m wind speed for the global oceans is available on a 1° grid and provides monthly means for the period of 1958 to present and daily means for 1985 to present. This product integrates satellite observations with mooring and ships reports and reanalyzed surface meteorology from atmospheric models (Yu et al. 2008).

3 Results and discussion

Here, we discuss the impact of ocean coupling and horizontal atmospheric grid resolution on simulated SST, 10-m wind speed, and NH and its components. Our discussion focuses on simulations for the period 2001–2003. The differences between coarse-coupled and -uncoupled simulations (CPL44 vs. CCLM44) for the periods 1980–2011 and 2001–2003 are systematic. Therefore, the choice of a shorter period (2001–2003) does not affect the results of our study. However, for the sake of completeness, further comparisons of long-term simulations for the period of 1980–2011 are presented in the supplementary information (SI). It is worth noting here that we have explicitly analyzed the impact of the European 2003 heat-wave in our results. We found that ocean coupling does not change the intensity of heat-waves, which is also shown by Tomassini and Elizalde (2012). The total mean difference (MD) and root mean square error (RMSE) of daily values of the respective seasons are used as simple statistical measures in the following discussions.

3.1 SST

Figure 1 illustrates the effect of ocean coupling and of a finer atmospheric grid resolution on the mean seasonal simulated SST. The first row of Fig. 1 compares the SST simulated with the high-resolution uncoupled CCLM08 with the observed OISST. The differences are small, as expected, because analyzed SST observations are applied in the ERA-Interim SST, thus forcing the CCLM08 simulation. The differences are larger near the coastal areas (RMSE ranges from 0.5 to 1.1 °C), mainly due to interpolation artifacts in preparing ERA-Interim SSTs as forcing data.

The second and third rows of Fig. 1 compare the CPL08 SST simulation with observations and with the CCLM08 simulation, respectively. The CPL08 is warmer in winter (MD = 1.3 °C) and colder in summer (MD = −1.0 °C). Locally, these differences are up to ±3 °C (RMSE is 1.8 °C in winter and 1.2 °C in summer). This finding can partly be explained by the calculation method of SST in the coupled model: the SST is the mean temperature of the uppermost ocean layer, which is 1 m thick in NEMOMED12 (Lebeaupin Brossier et al. 2014). The observed SSTs are derived from satellite radiometer data representative of the uppermost few millimeters of the ocean. The annual mean value of CPL08 over the simulated period is 0.3 °C higher than CCLM08. Similar differences can be seen in the coarse-coupled (CPL44) simulation for the period of 1980–2011 (Fig. SI-1).

A comparison of CPL08 and CPL44 reveals that the atmospheric grid resolution also impacts the simulated SST (Fig. 1, last row). The CPL08 is colder than CPL44 in all seasons except summer. The winter warm bias in the coarser CPL44 simulation is stronger (1.8 vs. 1.3 °C) than CPL08, which might be due to better near-coastal simulation of 10-m wind speed in the finer atmospheric grid in CPL08 (discussed in detail in the next subsection) and in return better SST in CPL08. Higher wind speed increases the latent heat release and hence lowers the SST. The local differences in summer between coarse and fine simulations are almost as large as they are in winter (RMSE values of 0.8 and 1.0 °C, respectively). This disappearing systematic effect correlates with the smaller wind speeds in summer in the Mediterranean basin.

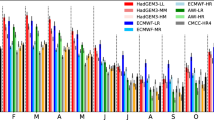

Figure 2 shows the annual cycles of basin-averaged SSTs of the different simulations and the observation data. As noted above, the SSTs of the uncoupled simulation are similar to the observational data. The SSTs calculated in the coupled simulations reveal a warm bias in winter and a smaller cold bias in summer. The high-resolution simulation improves this bias slightly.

3.2 10-m wind speed

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of ocean coupling and of a finer atmospheric grid resolution on simulated seasonal 10-m wind speed. The comparison of simulated and observed 10-m wind speed reveals that the differences are particularly large in near-coastal areas, especially in areas that are associated with intense wind systems (e.g., Vendaval and Levante winds in the Alboran Sea; Mistral and Tramontane in the Gulf of Lions and Ligurian Sea; Bora winds in the Adriatic Sea; Libeccio winds in the central Mediterranean Sea). These wind systems are generally more intense in winter and autumn (Perry 2001). The first row of Fig. 3 compares the 10-m wind speed simulated in high-resolution uncoupled CCLM08 with the NOAA observations. The CCLM08 underestimates the mean 10-m wind speed with MD = −1.2 ms−1 in winter (observed mean 8.1 ms−1) and −0.2 ms−1 in summer (observed mean 4.5 ms−1). Locally, CCLM08 underestimates the 10-m wind speed by up to 3 ms−1 in winter and autumn (RMSEs, 1.4 and 1.0 ms−1, respectively). These differences are slightly reduced in CPL08 (winter: MD = −0.8 ms−1, RMSE = 1.1 ms−1), except in summer (MD = −0.5 ms−1, RMSE = 0.7 ms−1; Fig. 3, row 2). Figure 3, row 3 shows a comparison of 10-m wind speed in the CPL08 and CCLM08 simulations. The ocean coupling improves the 10-m wind speed simulation by about 1% over the simulated period; the largest improvement (about 5%) occurs in the winter (Fig. 3, row 4). This correlates with a deepening of the surface pressure in CPL08 (0.5–1.0 hPa) compared to CCLM08, yielding increased pressure gradients in winter and vice versa in summer (Fig. SI-4).

As in Fig. 1, but for 10-m wind speed (in ms−1)

The last row of Fig. 3 shows that the impact of atmospheric grid resolution is more pronounced than the impact of coupling in the simulation experiment set-up that we tested. The high-resolution coupled CPL08 revealed an improvement over the coarse-coupled CPL44 of about 2–3 ms−1 (RMSE = 0.6–1.0 ms−1), mostly in near-coastal areas. The use of a fine atmospheric grid improved the simulation of fine-scale orography-related local and regional processes (such as in Louka et al. 2008 and Obermann et al. 2016). The high resolution simulation revealed an added value of 4–7%, with the minimum in spring and maximum in winter. The comparison of the high-resolution uncoupled CCLM08 to the coarse-resolution uncoupled CCLM44 exhibited similar patterns (not shown here). Additionally, the higher-resolution simulations showed lower sea level pressure (1.5–2 hPa) and higher pressure gradients (Fig. SI-5), resulting in higher wind speeds during the winter half of the year.

Figure 4 shows the annual cycle of basin-averaged 10-m wind speeds of different simulations and observation data. The simulated and observed wind fields attained their maximums during winter and their minimums in summer. With a fine atmospheric grid and ocean coupling, the simulated 10-m wind speeds were closest to the observation data, although coupling has an adverse impact in summer (consistent with a negative bias in SST and higher sea level pressure than without coupling).

3.3 Sea surface heat fluxes

The Mediterranean Sea exchanges energy with the atmosphere through turbulent and radiative fluxes (Eq. 1). Here, we compare the NH and its components simulated in coupled CPL08 and uncoupled CCLM08 models with the OAFlux observations. Conversely, a detailed comparison of high-resolution CPL08 and coarse CPL44 is provided in the SI (Fig. SI-3). Additionally, the mean values for the periods 2001–2003 and 1980–2011 over the Mediterranean Sea for all the simulations are summarized in Table 1. The heat loss terms, LH, SH, and LW, are positive upward and the heat gain terms, SW and NH, are positive downward.

Figure 5 compares the turbulent fluxes LH and SH—as simulated with the high-resolution uncoupled CCLM08 and coupled CPL08—with the OAFlux observations. The high-resolution uncoupled CCLM08 underestimates LH in winter (MD = −31 Wm−2) and autumn (MD = −21 Wm−2), and it overestimates LH in summer (MD = 14 Wm−2) and slightly overestimates LH in spring. The annual mean LH is approximately 10% smaller than the observational data (Table 1). The spatial patterns reveal that the differences are largest in the Gulf of Lions, the Ionian Sea, and the eastern basin of the Mediterranean Sea. The ratios of RMSE and mean observation values are 0.26, 0.11, 0.28, and 0.20 for winter, spring, summer, and autumn, respectively. The LH values in CPL08 are better; the ratios have values of 0.14, 0.19, 0.17, and 0.18, respectively. The annual mean value is approximately 5% smaller than the observational data (Table 1).

Mean differences latent heat and sensible heat (in Wm−2; positive upward) between uncoupled CCLM08 (upper rows) and coupled CPL08 (lower rows) with OAFlux observations for winter, spring, summer, and autumn (columns) in the period 2001–2003. The numbers given in the panels are the total mean differences (MD) and the mean RMSEs as MD/RMSE

The SH flux is smaller than the observational data in absolute value (Table 1; Fig. 5) but larger near the northern coastlines (where the wind speed differences are large as well) compared to other areas of the Mediterranean Sea. On average, the coupled CPL08 (20% underestimation) is better than CCLM08 (33% underestimation; Table 1). Table 1 shows that the high-resolution simulations represent the turbulent fluxes better than the coarser-resolution simulations. Turbulent fluxes are less well simulated in the coarse simulations (Table 1; Fig. SI-3).

Figure 6 compares the LW and SW surface radiation fluxes simulated in CCLM08 and CPL08 with the observations. Long-wave radiation is generally overestimated in winter (MD 17–19 Wm−2; mean absolute value 73 Wm−2) and underestimated in the eastern Mediterranean Sea in summer. Short-wave radiation is overestimated by 17 and 18 Wm−2 in spring, with mean differences below 10 Wm−2 in the other seasons. Therefore, the impact of coupling is minor; there is about a 10% average error in LW and a 4% average error in SW, errors in SW and LW compensating each other. The coarser CPL44 and CCLM44 simulations are better (4 and 1% errors in LW and SW, respectively; Table 1) than the finer CPL08 and CCLM08 simulations (for seasonal mean comparison see SI-3). It should be noted that the LW observational data exhibit large inconsistencies (Sevault et al. 2014).

As in Fig. 5 but for longwave (in Wm−2; positive upward) and shortwave radiations (in Wm−2; positive downward)

A comparison of simulated NHs with observation data is given in Fig. 7. This figure shows that CCLM08 largely overestimates NH in winter and autumn and underestimates NH in summer; smaller errors are present in spring. This situation largely occurs because of the errors in LH, which is better simulated in the coupled CPL08 (except in autumn). In absolute numbers, winter NHs are modeled most poorly because of the large errors in LH simulation. In relative numbers, the autumn NH values are worse in CCLM08 and CPL08 compared to the observations (errors of 30%). Overall, the coupled NH simulations performed better than the uncoupled, and the finer resolution simulations improve upon the coupled NH simulations.

As in Fig. 5, but for neat heat flux (in Wm−2; positive downward)

Table 1 shows that there are compensating errors in the simulated SW and LW fluxes. This error compensation explains why NH is better simulated in the high-resolution models despite worse scores in radiation fluxes. This finding is also detectable in the annual cycle of NH (Fig. 8). Generally, in open oceans, LH controls the variability of NH when SW becomes less important (Alexander et al. 2002), which also applies to the Mediterranean Sea (Josey et al. 2011; Papadopoulos et al. 2012) and is confirmed here. A better representation of LH due to the inclusion of ocean coupling results in a better representation of NH.

The NH is balanced by the net heat through the Strait of Gibraltar, which is also known as the closure hypothesis. Using this hypothesis, Sanchez-Gomez et al. (2011) estimated NH = −1 ± 8 Wm−2 using observational data. Given this estimate, the OAFlux value of −10 Wm−2 might be too negative. The mean NH values of our uncoupled simulations are probably too positive, with 7 Wm−2 (CCLM08) and 14 Wm−2 (CCLM44). However, the coupled simulations have mean NH values of −1 and 1 Wm−2 in CPL08 and CPL44, respectively, and fit very well. Given the utmost importance of the sign of the NH value for the interplay between the inflow to the Strait of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean overturning circulation, the high-resolution coupled CPL08 simulation shows the most realistic estimate of NH. This finding confirms that ocean–atmosphere coupling is important for physically consistent simulations of the Mediterranean climate (e.g., Somot et al. 2008; Sevault et al. 2014).

Because the results showed the primary impact of errors in the LH simulations, we further investigated the important variables for its parameterization. LH largely depends on the difference between the sea surface specific humidity (Qs) and the air specific humidity (Qa), along with the 10-m wind speed. As discussed above, the wind speed was underestimated in all the simulations, and the best results were obtained by the high-resolution CPL08 and CCLM08. This explains why LH was better simulated in the higher-resolution setups (Table 1). Figure 9 shows that the specific humidity difference was larger (smaller) in winter (summer) in CPL08 than in CCLM08, which is consistent with warmer/colder SSTs (compare Fig. 1). This finding explains why CPL08 performs better than CCLM08 (Fig. 3; Table 1).

Sensible heat flux mainly depends on the difference between SST and air temperature (Ta), along with 10-m wind speed. Better wind speed simulations with high-resolution CPL08 and CCLM08 than with the coarse-resolution setups are consistent with better SH simulations (Table 1). Figure 9, row 2 shows that coupling had an impact on the temperature difference, which is larger (smaller) in winter (summer) in CPL08 than in CCLM08, which in turn influenced SH (Fig. 5; Table 1); CPL08 simulates the winter and annual-mean SH slightly better than CCLM08.

Ocean coupling had a minor impact on the LW and SW radiation fluxes. However, the performances of CPL08 and CCLM08 are worse than those of the coarse experiments with respect to radiative fluxes: outgoing LWs and incoming SWs are overestimated. The final row of Fig. 9 shows that winter cloud cover is 10% smaller in CPL08 than in CPL44. This result is remarkably consistent with the overestimated LWs in winter (Fig. 6). Short-wave radiation is overestimated in CPL08 and CCLM08, mainly in the spring and mainly in the southern part of the sea (Fig. 6). These results fit well with the cloud cover difference pattern (Fig. 9). Therefore, a higher resolution seems to have an adverse impact on the parameterization of clouds in COSMO-CLM.

3.4 SST diurnal variations

In CCLM44 and CCLM08, daily constant SST values were provided by ERA-Interim. Consequently, there was no diurnal variation in CCLM SST, except by interpolation in time and space (surface variations over land have an impact on near-coastal SSTs). This is shown in Fig. 10, with a clear diurnal variation in the observation data (SST measured at the Lion buoy) and in the coupled simulations. Not surprisingly, the mean SSTs of the CCLM simulation fit better than those of the CPL simulations (the bias of CPL08 and CCLM08 compared with the Lion buoy data is −1.2 and −0.1 °C, respectively); this is not true, however, for the temporal variation of SST. Figure 11 shows the SST amplitude differences simulated by CPL08 and CCLM08_SSTavg. The mean amplitude was highest in spring and summer seasons with 0.2 and 0.3 °C, respectively (the seasons with the largest amplitudes in NH and the smallest vertical mixing in the sea); the largest values occurred in the central Mediterranean. The minimum/maximum SST occurred at approximately 09:00/18:00 UTC. These amplitudes were on the same order of magnitude as the summer differences between the CPL08 and CCLM08 SSTs.

Therefore, we investigated the impact of sub-daily variability of SST. To this end, we smoothed the CPL08 SSTs over time (5-day block average; Fig. 10) and conducted an additional simulation CCLM08_SSTavg with prescribed smoothed SSTs. The diurnal variations were stronger during summer when SW radiations are higher and the ocean mixing layer depth is shallow. Figure 12 shows the impact of SST diurnal variations (largest during summer) on 10-m wind speed, LH, SH, and NH amplitudes. The impact on LW and SW was approximately zero (not shown here). Also, the impact on seasonal means was negligible (the summer mean differential for LH and SH between CPL08 and CCLM08_SSTavg is −0.6 and 0.6 Wm−2 compared with a difference between CPL08 and CCLM08 of 12 and 3 Wm−2, respectively). Therefore, SST diurnal variations were of minor importance for the mean seasonal state of the atmosphere. However, they modified the turbulent fluxes on a sub-daily timescale.

4 4. Conclusions

We have discussed the impacts of different grid-spacing (~50 vs. ~9 km) of the atmospheric RCM COSMO-CLM and the coupling of an ocean model (NEMOMED12) on simulations in the Mediterranean Sea area. Our primary goal was to achieve an optimum performance of the simulations in terms of ocean–atmosphere fluxes and therefore 10-m wind speed and net heat flux components.

Our results revealed that the fine-grid simulations represent the winds better (especially near the coastlines, as also found in Obermann et al. (2016) in the western Mediterranean Sea) than the coarse-grid simulations. This fact had a positive impact on the simulation of turbulent fluxes. Coupling an active ocean model further improved the turbulent fluxes despite a simulated SST bias against available observations. Radiative fluxes were slightly better simulated using the coarser grid-spacing. This is due to the slightly worse representation of cloud cover in the high-resolution simulations. In terms of the turbulent flux simulations, both the coupled fine-grid CPL08 and coarse-grid CPL44 performed better than their uncoupled counterparts. However, CPL08 obtained the most realistic estimate of net heat flux, with a negative value consistent with observations.

With the coupled COSMO-CLM/NEMOMED12 modeling system, we were able to simulate sub-daily SST variations. A sensitivity experiment revealed that the long-term means were only slightly affected if the daily mean SSTs were prescribed (as with using ERA-Interim SSTs) in regional climate modeling. As shown previously in the literature, sub-daily variations are essential for extreme events such as medicanes (Akhtar et al. 2014), but given the results presented here they are of minor importance for the mean atmospheric state in the Mediterranean.

The results presented show that the cloud cover parameterization in the COSMO-CLM should be reassessed. Given the uncertainties in the radiation fluxes shown and the findings in the literature (Nabat et al. 2013), the prescription of aerosol optical depths should be investigated as well. Also, model inter-comparison within the Med-CORDEX (http://www.medcordex.eu) project could be useful for assessing the source of uncertainty and different model physics/parameterizations, but it is also necessary to have high-resolution coupled simulations over longer time periods (~30 years) to obtain robust model climatologies. Further, this study could be extended to investigate the impact of sub-daily variations in SST on extreme events such as heavy precipitation and medicane events. Finally, a high-resolution coupled system, such as the one presented here, could be useful for studying the impact of climate change in the Mediterranean region.

Change history

20 April 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Akhtar N, BrauchJ, Dobler A, Bérenger K, Ahrens B (2014) Medicanes in an ocean-atmosphere coupled regional climate model. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 14:2189–2201. doi:10.5194/nhess-14-2189-2014

Alexander MA, Blade I, Newman M, Lanzante JR, Lau NC, Scott JD (2002) The atmospheric bridge: the influence of ENSO teleconnections on air-sea interaction over the global oceans. J Climate 15:2205–2231. doi:10.1175/1520&a>2.0.Co;2

Artale V, Calmanti S, Carillo A, Dell’Aquila A, Herrmann M, Pisacane G, Ruti PM, Sannino G, Struglia MV, Giorgi F, Bi X, Pal JS, Rauscher S, The PROTHEUS Group (2010) An atmosphere–ocean regional climate model for the Mediterranean area: assessment of a present climate simulation. Clim Dyn 35:721–740. doi:10.1007/s00382-009-0691-8

Beuvier J, Béranger K, Lebeaupin-Brossier C, Somot S, Sevault F, Drillet Y, Bourdallé-Badie R, Ferry N, Lyard F (2012) Spreading of the Western Mediterranean Deep Water after winter 2005: time scales and deep cyclone transport. J Geophys Res Oceans 117(C7)

Calmanti S, Artale V, Sutera A (2006) North Atlantic MOC variability and the Mediterranean Outflow: a box-model study. Tellus Ser A Dyn Meteorol Oceanogr 58(3):416–423. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0870.2006.00176.x

Dee DP, Uppala SM, Simmons AJ, Berrisford P, Poli P, Kobayashi S, Andrae U, Balmaseda MA, Balsamo G, Bauer P, Bechtold P, Beljaars ACM, van de Berg L, Bidlot J, Bormann N, Delsol C, Dragani R, Fuentes M, Geer AJ, Haimberger L, Healy SB, Hersbach H, Hólm EV, Isaksen L, Kållberg P, Köhler M, Matricardi M, McNally AP, Monge-Sanz BM, Morcrette JJ, Park BK, Peubey C, de Rosnay P, Tavolato C, Thépaut JN, Vitart F (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J R Meteorol Soc 137:553–597. doi:10.1002/qj.828

Dell’Aquila A, Calmanti S, Ruti P, Struglia MV, Pisacane G, Carillo A, Sannino G (2012) Impacts of seasonal cycle fluctuations in an A1B scenario over the Euro-Mediterranean. Clim Res. doi:10.3354/cr01037

Dubois C, Somot S, Calmanti S, Carillo A, Déqué M, Dell’Aquila A, Elizalde A, Gualdi S, Jacob D, L’Hévéder B, Li L, Oddo P, Sannino G, Scoccimarro E, Sevault F (2012) Future projections of the surface heat and water budgets of the Mediterranean Sea in an ensemble of coupled atmosphere–ocean regional climate models. Clim Dyn 39:1859–1884

Elguindi N, Somot S, Déqué M, Ludwig W (2009) Climate change evolution of the hydrological balance of the Mediterranean, Black and Caspian Seas: impact of climate model resolution. Clim Dyn 36:205–228

Fairall CW, Bradley EF, Godfrey JC, Wick GA, Edson JB, Young GS (1996) Cool-skin and warm-layer effects on sea surface temperature. J Geophys Res 101:1295–1308. doi:10.1029/95JC03190

Ferry N, Parent L, Garric G, Barnier B, Jourdain NC, the Mercator Ocean team (2010) Mercator global eddy permitting ocean reanalysis GLORYS1V1: description and results. Mercator Ocean Q Newslett 36:15–28

Gao X, Pal JS, Giorgi F (2006) Projected changes in mean and extreme precipitation over the Mediterranean region from a high resolution double nested RCM simulation. Geophys Res Lett 33:L03706. doi:10.1029/2005GL024954

Giorgi F (2006) Climate change hot-spots. Geophys Res Lett 33:L08707. doi:10.1029/2006GL025734

Herrmann M, Somot S (2008) Relevance of ERA40 dynamical downscaling for modeling deep convection in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Geophys Res Lett 35:L04607

Herrmann M, Somot S, Calmanti S, Dubois C, Sevault F (2011) Representation of daily wind speed spatial and temporal variability and intense wind events over the Mediterranean Sea using dynamical 594 downscaling: impact of the regional climate model configuration. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 11:1983–2001. doi:10.5194/nhess-11-1983-2011

Josey S (2003) Changes in the heat and freshwater forcing of the eastern Mediterreanean and their influence on deep water formation. J Geophys Res 108:1–18. doi:10.1029/2003JC001778

Josey SA, Somot S, Tsimplis M (2011) Impacts of atmospheric modes of variability on Mediterranean Sea surface heat exchange. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/2010jc006685

Kawai Y, Wada A (2007) Diurnal sea surface temperature variation and its impact on the atmosphere and ocean: a review. J Oceanogr 63:721–744

Kothe S, Panitz HJ, Ahrens B (2014) Analysis of the radiation budget in regional climate simulations with COSMO-CLM for Africa. Meteorol Z 23(2):123–141. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2014/0527

Lebeaupin Brossier C, Drobinski P (2009) Numerical high-resolution air-sea coupling over the Gulf of Lions during two tramontane/mistral events. J Geophys Res 114:D10110. doi:10.1029/2008JD011601

Lebeaupin Brossier C, Béranger K, Deltel C, Drobinski P (2011) The Mediterranean response to different space-time resolution atmospheric forcings using perpetual mode sensitivity simulations. Ocean Model 36:1–25. doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2010.10.008

Lebeaupin Brossier C, Béranger K, Drobinski P (2012) Sensitivity of the northwestern Mediterranean Sea coastal and thermohaline circulations simulated by the 1/12o-resolution ocean model NEMOMED12 to the spatial and temporal resolution of atmospheric forcing. Ocean Model 43–44:94–107. doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2011.12.007

Lebeaupin Brossier C, Bastin S, Béranger K, Drobinski P (2014) Regional mesoscale air-sea coupling impacts and extreme meteorological events role on the Mediterranean Sea water budget. Clim Dyn 44:1029–1051. doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2252-z

Levitus S, Antonov J, Boyer T (2005) Warming of the world ocean, 1955–2003. Geophys Res Lett 32:L02604. doi:10.1029/2004GL021592

Llasses J, Jordà G, Gomis D, Adloff F, Sannino G, Elizalde A, Harzallah A, Li L, Akthar N, Macías Moy D (2016) Heat and salt redistribution in the Mediterranean Sea in the Med-CORDEX model ensemble. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-016-3242-0

Louka P, Galanis G, Siebert N, Kariniotakis G, Katsafados P, Pytharoulis I, Kallos G (2008) Improvements in wind speed forecasts for wind power prediction purposes using kalman filtering. J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn 96(12):2348–2362. doi:10.1016/j.jweia.2008.03.013

Ludwig W, Dumont E, Meybeck M, Heussner S (2009) River discharges of water and nutrients to the Mediterranean and Black Sea: major drivers for ecosystem changes during past and future decades. Prog Oceanogr 80:199–217

Madec G, the NEMO Team (2008) NEMO Ocean Engine, Note Pôle Modél, 27. Inst Pierre-Simon Laplace, Paris

Nabat P, Somot S, Mallet M, Chiapello I, Morcrette J, Solmon F, Szopa S, Dulac F, Collins W, Ghan S, Horowitz LW, Lamarque JF, Lee YH, Naik Y, Nagashima T, Shindell D, Skeie R (2013) A 4-D climatology (1979–2009) of the monthly tropospheric aerosol optical depth distribution over the Mediterranean region from a comparative evaluation and blending of remote sensing and model products. Atmos Meas Technol 6:1287–1314

Obermann A, Bastin S, Belamari S, Conte D, Gaertner MA, Li L, Ahrens B (2016) Mistral and Tramontane wind speed and wind direction patterns in regional climate simulations. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-016-3053-3

Panthou, G, Vrac, M, Drobinski, P, Bastin S, Li L (2016) Impact of model resolution and Mediterranean sea coupling on hydrometeorological extremes in RCMs in the frame of HyMeX and MED-CORDEX. Clim Dyn. doi:10.1007/s00382-016-3374-2

Papadopoulos VP, Josey SA, Bartzokas A, Somot S, Ruiz S, Drakopoulou P (2012a) Large-scale atmospheric circulation favoring deep- and intermediate-water formation in the Mediterranean Sea. J Climate 25:6079–6091. doi:10.1175/Jcli-D-11-00657.1

Perry K (2001) Sea winds on QuikSCAT level 3 daily, gridded ocean wind vectors (JPL sea winds Project) guide document

Pettenuzzo D, Large WG, Pinardi N (2010) On the corrections of ERA-40 surface flux products consistent with the Mediterranean heat and water budgets and the connection between basin surface total heat flux and NAO. J Geophys Res 115:C06022. doi:10.1029/2009JC005631

Pimentel S, Haines K, Nichols NK (2008) Modeling the diurnal variability of sea surface temperatures. J Geophys Res 113:C11004. doi:10.1029/2007JC004607

Reynolds WR, Smith TM, Liu C, Chelton DB, Casey KS, Schlax MG (2007) Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J Climate 20:5473–5496. doi:10.1175/2007JCLI1824.1

Ritter B, Geleyn J-F (1992) A comprehensive radiation scheme for numerical weather prediction models with potential applications in climate simulations. Mon Weather Rev 120(2):303–325

Rixen M (2012) MEDAR/MEDATLAS-II, GAME/CNRM. doi:10.6096/HyMeX.MEDAR/MEDATLAS-II.20120112

Rockel B, Will A, Hense A (2008) A spectral nudging technique for dynamical down-scaling purposes. The regional climate model COSMO-CLM (CCLM). Meteorol Z 17:347–348

Roether WB, Manca B, Klein B, Bregant, Georgopulos D, Beitzel V, Kovacevic V, Lucchetta A (1995) Recent changes in eastern Mediterranean deep water. Science 271:333–335

Ruiz S, Gomis D, Sotillo MG, Josey SA (2008) Characterization of surface heat fluxes in the Mediterranean Sea from a 44-year high-resolution atmospheric dataset. Glob Plan Chan 63:258–274

Ruti PM, Marullo S, D’Ortenzio F, Tremant M (2008) Comparison of analyzed and measured wind speeds in the perspective of oceanic simulations over the Mediterranean basin: analyses, QuikSCAT and buoy data. J Mar Syst 70:33–48. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.02.026

Ruti PM, Somot S, Giorgi F, Dubois C, Flaounas E, Obermann A, Dell’Aquila A, Pisacane G, Harzallah A, Lombardi E, Ahrens B, Akhtar N, Alias A, Arsouze T, Aznar R, Bastin S, Bartholy J, Béranger K, Beuvier J, Bouffies-Cloché S, Brauch J, Cabos W, Calmanti S, Calvet J-C, Carillo A, Conte D, Coppola E, Djurdjevic V, Drobinski P, Elizalde-Arellano A, Gaertner M, Galàn P, Gallardo C, Gualdi S, Goncalves M, Jorba O, Jordà G, L’Heveder B, Lebeaupin-Brossier C, Li L, Liguori G, Lionello P, Maciàs-Moy D, Nabat P, Onol B, Rajkovic B, Ramage K, Sevault F, Sannino G, Struglia MV, Sanna A, Torma C, Vervatis V (2015) MED-CORDEX initiative for Mediterranean Climate studies. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00176.1

Sanchez-Gomez E, Somot S, Josey SA, Dubois C, Elguindi N et al (2011) Evaluation of Mediterranean Sea water and heat budgets simulated by an ensemble of high resolution regional climate models. Clim Dyn 37:2067–2086

Sanna A, Lionello P, Gualdi S (2013) Coupled atmosphere ocean climate model simulations in the Mediterranean region: effect of a high-resolution marine model on cyclones and precipitation. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 13:1567–1577, doi:10.5194/nhess-13-1567-2013

Sevault F, Somot S, Alias A, Dubois C, Lebeaupin-Brossier C, Nabat P, Adloff F, Déqué M, Decharme B (2014) A fully coupled Mediterranean regional climate system model: design and evaluation of the ocean component for the 1980–2012 period. Tellus A. doi::10.3402/tellusa.v66.23967

Shinoda T, Hendon HH (1998) Mixed layer modeling of intraseasonal variability in the tropical western Pacific and Indian Oceans. J Climate 11:2668–2685

Somot S, Sevault F, Déqué, M, Crépon M (2008) 21st century climate change scenario for the Mediterranean using a coupled atmosphere–ocean regional climate model. Global Planet Change 63:112–126

Stanev EV, Peneva EL (2002) Regional sea level response to global climatic change: Black Sea examples. Global Planet Changes 32:33–47

Sui C-H, Li X, Lau K-M, Adamec D (1997) Multiscale air–sea interactions during TOGA COARE. Mon Weather Rev 125:448–462

Sverdrup HU, Johnson MW, Fleming RH (1942) The oceans: their physics, chemistry and general biology. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, p 1087

Takaya Y, Bildot J-R, Beljaars AC, Janssen PM (2010) Refinements to a prognostic scheme of skin sea surface temperature. J Geophys Res 115:C06009. doi:10.1029/2009JC005985

Theocharis A, Nittis K, Kontoyiannis H, Papageorgiou E, Balopoulos E (1999) Climatic changes in the Agean Sea influence the eastern Mediterranean thermohaline circulation (1986–1997). Geophys Res Lett 26:1617–1620

Tomassini L, Elizalde A (2012) Does the Mediterranean Sea influence the European summer climate? The anomalous summer 2003 as a test bed. J Climate. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00330.1

Valcke S (2013) The OASIS3 coupler: a European climate modelling community software. Geosci Model Dev 6:373–388. doi:10.5194/gmd-6-373-2013

Webster PJ, Clayson CA, Curry JA (1996) Clouds, radiation, and the diurnal cycle of sea surface temperature in the tropical western Pacific. J Climate 9:1712–1730. doi:10.1175/1520-0442

Weller RA, Anderson SP (1996) Surface meteorology and air–sea fluxes in the western equatorial Pacific warm pool during the TOGA coupled ocean–atmosphere response experiment. J Climate 9:1959–1990

Yokoyama R, Tanba S, Souma T (1995) Sea surface effects on the sea surface temperature estimation by remote sensing. Int J Remote Sens 16:227–238

Yu L, Jin X, Weller RA (2008) Multidecade Global Flux Datasets from the Objectively Analyzed Air-sea Fluxes (OAFlux) Project: latent and sensible heat fluxes, ocean evaporation, and related surface meteorological variables. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, OAFlux Project Technical Report OA-2008-01, Woods Hole

Zeng X, Beljaars A (2005) A prognostic scheme of sea surface skin temperature for modeling and data assimilation. Geophys Res Lett 32:L14605. doi:10.1029/2005GL023030

Zhang C, Dong M, Gualdi S, Hendon HH, Maloney ED, Marshall A, Sperber KR, Wang W (2006) Simulations of the Madden–Julian oscillation by four pairs of coupled and uncoupled global models. Clim Dyn 27:573–592

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Center for Scientific Computing (CSC) of the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main and the Deutsches Klimarechenzentrum (DKRZ) for providing computational facilities. B. Ahrens acknowledges support by Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (BiK-F), Frankfurt am Main. We acknowledge Cindy Lebeaupin Brossier, Jonathan Beuvier, Thomas Arzouse, Samuel Somot and Philippe Drobinski for their help regarding NEMOMED12 and French GIS and GMMC which have supported NEMOMED12 model. B. Ahrens and N. Akhtar acknowledge the support from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under grant MiKliP II (FKZ 01LP1518C). This work is part of the Med-CORDEX initiative (http://www.medcordex.eu) supported by the HyMeX (http://www.hymex.org).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is a contribution to the special issue on Med-CORDEX, an international coordinated initiative dedicated to the multi-component regional climate modelling (atmosphere, ocean, land surface, river) of the Mediterranean under the umbrella of HyMeX, CORDEX, and Med-CLIVAR and coordinated by Samuel Somot, Paolo Ruti, Erika Coppola, Gianmaria Sannino, Bodo Ahrens, and Gabriel Jordà.

In the original publication of this article, the family name of corresponding author has been published incorrectly; this error has now been corrected.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Akhtar, N., Brauch, J. & Ahrens, B. Climate modeling over the Mediterranean Sea: impact of resolution and ocean coupling. Clim Dyn 51, 933–948 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3570-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3570-8