Abstract

Meningitis is a rare but serious complication in patients with Currarino syndrome. We present a 6-year-old girl with a fulminant meningitis due to an enterothecal fistula involving the anterior sacral meningocele. Initial treatment consisted of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic therapy and laparoscopic construction of a deviating double-loop ileostomy. This was followed by an elective posterior neurosurgical approach with a sacral laminectomy, evacuation of the empyema, and securing the disconnection of the anterior meningocele from the thecal sac, 10 days after initial hospital admission. The girl made a good postoperative recovery. The treatment strategy in the setting of meningitis due to an inflamed anterior meningocele is discussed and the available literature on the topic is reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1981, Guido Currarino et al. were the first to describe a triad consisting of (1) partial sacral agenesis; (2) presacral mass (anterior meningocele, enteric cyst, teratoma); and (3) anorectal malformation/stenosis [10]. There are no generally accepted guidelines about the indication and timing of surgical correction of an anterior sacral meningocele. Neither are there known risk factors predicting which patients with Currarino syndrome are prone to develop meningitis due to an enterothecal fistula. It is also unknown whether there is a relationship between (increase of) the size of the anterior meningocele and the chance of developing an enterothecal fistula. Different surgical approaches (anterior/posterior/sagittal) to close and resect the meningocele have been reported in the literature [25]. Here, we present our experience with a young patient with Currarino syndrome suffering from meningitis due to an enterothecal fistula and give an overview of the available literature on the topic.

Case report of an illustrative patient

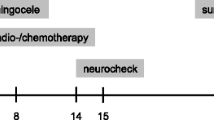

A 6-year-old girl presented with headache, drowsiness, and opisthotonus. She had been diagnosed with familial Currarino triad with associated constipation and micturition problems. Repeated lumbosacral MRI scans over the years had revealed slight increase of the anterior meningocele (see Fig. 1). Four days before admission, the patient was treated with antibiotics in another hospital because of a suspected urinary tract infection. At presentation in the emergency room, she was drowsy (GCS 3-5-2) with severe opisthotonic posturing (see Fig. 2a), but without focal neurological signs. Her body temperature was 36.6 °C. Blood leucocyte count and C-reactive peptide were 23.2 × 109 /L and 214 mg/L, respectively. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed a pleocytosis with 6659 × 106 /L cells and glucose < 0.1 mmol/L. Antibiotic treatment was immediately started and consisted of intravenous ceftazidime and metronidazole for 6 weeks. Culture of the CSF rendered Streptococcus anginosus (milleri) and Bacteroides fragilis. Because of the multimicrobial culture and her medical history, an enterothecal fistula was suspected. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the lumbosacral region revealed inflammation of the anterior meningocele with abscess formation (see Fig. 2b).

Multidisciplinary rounds with pediatric neurologists, pediatric surgeons, pediatricians, microbiologists, and neurosurgeons resulted in the decision to first perform a laparoscopic deviating double-loop ileostomy in the acute stage, in order to stop the inflow of enteral commensals in the CSF space and inflamed retroperitoneal and epidural area. A few days after the formation of an ileostomy, a contrast study of the rectal stump confirmed leaking of contrast through a rectal fistula to the area of the anterior meningocele. Ten days after hospital admission, a posterior sacral laminectomy was performed with evacuation of a large amount of empyema and debris from the anterior meningocele and the region around the sacral roots. There was severe fibrosis in the operating field. The connection between the anterior meningocele and thecal sac had closed spontaneously due to inflammation. No patent fistula was found.

After uncomplicated surgery, the clinical course was dominated by the aftermath of the fulminant meningitis. Postoperative MRI confirmed obliteration of the anterior sacral meningocele/enterothecal fistula and a decline of inflammation (see Fig. 3). Initially, the ventricular system was dilated, which was managed by intermittent lumbar CSF-taps. No internal CSF shunt was needed as the hydrocephalus resolved after recovery from the meningitis. Successful restoration of the ileostomy was performed several months later. The girl made a good physical and neurological recovery.

Review of the literature

In an attempt to collect data supportive for any specific strategy or approach, we performed a literature search on the topic of Currarino syndrome and meningitis in the databases of PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase, using the following search terms: [currarino], [meningitis], [anterior meningocele], and [inflammation]. The search rendered 37 publications describing 38 patients (Table 1). All were single case studies, except for one article describing two young infants suffering from the condition. The series comprises 17 pediatric patients and 20 adult patients (information on the age of one patient missing). The known female predominance of Currarino syndrome was confirmed with a F:M ratio of 24:13 (information on the gender of one patient missing). These case reports show that meningitis due to formation of an enterothecal fistula can be fatal [1, 16, 17]. In the series here described, a posterior surgical approach was chosen in 16 patients and an anterior surgical approach was chosen in 3 patients. For 16 patients, the surgical technique was not described in detail. In 3 cases, no surgery was performed (these 3 cases related to the three deceased patients in the series). Concerning the timing of surgery in the setting of meningitis and an infected meningocele, only 8 publications give adequate information. The timing of surgery ranged between day 1 and day 22 after hospital admission (and starting of antibiotic therapy), with a mean of 16 days and a median of 21 days before surgical correction of the fistula and the meningocele. For two patients, it was decided to plan the surgical repair in elective setting, after initial discharge home from the hospital when the meningitis was treated sufficiently (this included one patient with aseptic meningitis due to a dermoid tumor).

Discussion

In the case presented, it was decided to first perform an ileostomy, to be completely sure of a stop of leaking of intestinal microbial flora through the enteral fistula(s). This was followed by an elective posterior neurosurgical exploration. This seems to be an effective strategy. In the literature, we noticed the preference for a posterior approach in the situation of severe inflammation. This is in line with our experience in the case here described. In a posterior approach, important neurological structures are directly visualized and can be spared. A detethering procedure, for example cutting of the filum terminale, or removal of an intradural tumor (e.g., dermoid or teratoma), is conveniently possible during the same approach. A possible disadvantage is the suboptimal view on the rectum and the retroperitoneal/enteral anatomy. This is especially true in a situation of severe inflammation. In our experience, successful surgical closing of an enteral defect in the setting of active inflammation is not possible. Hence, a temporary ileostomy is an indispensable and elegant solution to overcome this problem. It is known from a significant body of literature, mainly from the GE-surgical field, that rectal fistula will close spontaneously if there is no passage of fecal material for some time because of an ileostomy [24].

The current available literature on the topic of meningitis, due to an inflamed anterior meningocele caused by an enterothecal fistula, is limited to case reports only. Therefore, evidence-based guidelines/protocols for Currarino patients developing meningitis due to an enterothecal fistula cannot be formulated. There is no high-quality literature on the natural history of Currarino patients with an anterior sacral meningocele to justify the prophylactic surgical correction of an anterior meningocele in all Currarino patients, solely aiming to prevent meningitis. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one case of meningitis are unavailable. If the patient experiences other clinical symptoms that could be alleviated by surgical correction of the anterior sacral meningocele, this would of course justify a more aggressive surgical strategy towards closure and resection of the meningocele.

Conclusion

The present case and review of the literature illustrates that in patients with Currarino syndrome potentially lethal meningitis can occur due to the development of an enterothecal fistula. In our own limited experience and supported by the literature, the construction of an ileostomy in the acute stage seems a safe and rational start of the (surgical) treatment, together with administration of high-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Subsequent surgical treatment of the enterothecal fistula and infected anterior sacral meningocele can be performed in an elective procedure, as soon as the patient has recovered from the most severe symptoms of the meningitis. A posterior approach is most often described in the literature, and seems to offer the best anatomical overview in the setting of (recent) inflammation. There is currently no supportive evidence for early prophylactic surgery in Currarino patients with an anterior sacral meningocele to prevent meningitis.

References

Al Qahtani HM, Aljoqiman KS, Arabi H, Al Shaalan H, Singh S (2016) Fatal meningitis in a 14-month-old with Currarino triad. Case reports in radiology 2016:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1346895

Antuna-ramos A, Garcia-Fructoso G, Alamar-Abril M, Guillén-Quesada A, Costa-Clara y JM (2011) Meningocele sacro anterior oculto. Neurocirugia 22:342–346

Bal S, Kurtulmus¸ K, Koçyig H, Gürgan (2004) A case with cauda Equina syndrome due to bacterial meningitis of anterior sacral Meningocele. Spine 29(14):E298–E299

Bergeron E, Roux A, Demers J, Vanier LE, Moore L (2010) A 40-year-old woman with cauda equina syndrome caused by rectothecal fistula arising from an anterior sacral meningocele: case report. Neurosurgery 67:E1464–E1468

Bhatia S, Tullu MS, Date NB, Muzumdar D, Muranjan M, Lahiri KR (2010) Anterior sacral pyocele with meningitis: a rare presentation of occult spinal dysraphism with congenital dermal sinus. J Child Neurol 25(11):1393–1397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073810365010

Blond MH, Borderon JC, Despert F, Laugier J, Maheut J, Robert M, Sirinlli D (1991) Anterior sacral meningocele associated with meningitis. Paediatr Infect Dis J 10(10):783–784

Braczynski AK, Brockmann MA, Scholz T, Bach JP, Schulz JB, Tauber SC (2017) Anterior sacral meningocele infected with fusobacterium in a patient with recently diagnosed colorectal carcinoma - a case report. BMC Neurol 17(1):212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0992-1

Calleja Aguayo E, Estors Sastre B, Bragagnini Rodriguez P, Fustero de Miguel D, Gonzalez Martinez-Pardo N, Elias Pollina J (2012) Triada de Currarino: sus diferentes formas de presentacion. Cir Pediatr 25:155–158

Chou IC, Mak SC, Lin TP, Chi CS, Pen HC (2002) Bacterial meningitis of an infant with Currarino triad. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 43(5):288–290

Currarino G, Coln D, Votteler T (1981) Triad of anorectal, sacral and presacral anomalies. AJR 137:395–398

Emans PJ, Kootstra G, Marcelis CLM, Beuls EAM, van Heurn LWE (2005) The Currarino triad: the variable expression. J Pediatr Surg 40:1238–1242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.05.004

Fitouri Z, Ben Slima S, Matoussi N, Aloui N, Bellagha I, Kechrid A, Ben Becher S (2007) Syndrome de Currarino cause rare de méningites purulentes récidivantes. Med Mal Infect 37:S264–S267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2006.10.008

Fitzpatrick MO, Taylor WAS (1999) Anterior sacral meningocele associated with a rectal fistula. J Neurosurg (Spine1) 91:124–127

Fiumara F, Foti N, Gambardella A, Mazzeo A, Oliveri RL, Pagano VD, Quattrone A (1989) Purulent meningitis due to spontaneous anterior sacral meningocele perforation. Case report. Ital J Neurol Sci 10:211–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02333622

Fleury J, Picherot G, Cretolle C, Podevin G, David A, Caillon J, Roze JC, Gras-le Guen C (2007) Currarino syndrome as an etiology of a neonatal Escherichia coli meningitis. J Perinatol 27:589–591. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211783

Funayama CAR, de Turcato MF, Moura-Ribeiro R, Rocha GM, Pina Neto JM, Moura-Ribeiro MVL (1995) Recurrent meningitis in a case of congenital anterior sacral meningocele and agenesis of sacral and coccygeal vertebrae. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 53(4):799–801. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X1995000500016

Ganeshalingham A, Buckley D, Shaw I, Freeman JT, Wilson F, Best E (2014) Bacteroides fragilis concealed in an infant with Escherichia coli meningitis. J Paediatr Child Health 50:78–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12394

Guerin JM, Leibingerl F, Raskine L, Ekheriad JM (2000) Polymicrobial meningitis revealing an anterior sacral meningocele in a 23-year-old woman. J Inf Secur 40(2):195–197. https://doi.org/10.1053/jinf.1999.0617

Haga Y, Cho H, Shinoda S, Masuzawa T (2003) Recurrent meningitis associated with complete Currarino triad in an adult-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 43:505–508

Hatano A, Akiyama K, Nagayama M, Takagi S (2006) Case of Marfan’s syndrome with anterior sacral meningocele along with recurring bacterial meningitis. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 46(9):658–660

Kansal R, Mahore A, Dange N, Kukreja S (2012) Epidermoid cyst inside anterior sacral meningocele in an adult patient of Currarino syndrome manifesting with meningitis. Turk Neurosurg 22(5):659–661. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3985-10.1

Kiefer AS, Gupta P, Kirmani S, Schwartz K, Henry N, Fischer PR (2009) Treatment-resistant meningitis leading to the diagnosis of currarino syndrome: a case report. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28:547–549. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e3181945875

Koksal A, Canyigit M, Kara T, Ulus A, Gokbayir H, Sarisahin M (2011) Unusual presentation of an anterior sacral meningocele: magnetic resonance imaging, multidetector computed tomography, and fistulography findings of bacterial meningitis secondary to a rectothecal fistula. Jpn J Radiol 29:528–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-011-0582-x

Martin ST, Vogel JD (2012) Intestinal stomas: indications, management, and complications. Adv Surg 46:19–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yasu.2012.04.005

Massimi L, Calisti A, Koutzoglou M, Di Rocco C (2003) Giant anterior sacral meningocele and posterior sagittal approach. Childs Nerv Syst 19:722–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-003-0814-1

Miletic D, Poljak I, Eskinja N, Valkovic P, Sestan B, Troselj-Vukic B (2008) Giant anterior sacral meningocele presenting as bacterial meningitis in a previously healthy adult. Orthopedics 31(2):182–184

Monseaux C, Coulon J-M, Etosse A, Nicomette-Bardel J, Regrain E, Peruzzi P, Boyer F-C (2013) Paraplegia after meningoencephalitis complicated by an arachnoisis in a patient with a Currarino syndrome. About a case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 56S:e82–e83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2013.07.451

Morgenstern IA, Bach FA, Martinez S, Martin-Nalda A, Vazquez Mendez E, Pumarola Segura F, Soler-Palacin P (2015) Recurrent meningitis due to anatomical defects: the bacteria indicates its origin. An Pediatr 82(6):388–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anpedi.2014.09.008

O’Riordain DS, O’Connell PR, Kirwan WO (1991) Hereditary sacral agenesis with presacral mass and anorectal stenosis: the Currarino triad. Br J Surg 78:536–538

Page Y, Thevenet D, Bertrand M, Chatard N, Gery P, Barral FG, Tardy B, Bertrand JC (1990) Polymicrobial meningitis revealing a meningorectal fistula of an anterior sacral meningocele. Clin Intensive Care 1(1):29–31

Patnaik S, Mohapatra M, Satpathy DK, Das S, Mohanty AK (2013) Anterior sacral meningocele with spinal epidural abscess: a case report with review of literature. J Pediatr Neurol 11:141–145

Paul P, Tiwari M, Kumar H (2015) Anterior sacral meningocele presenting with purulent rectal discharge and altered mental status. Neurol Clin Pract 5:89–90. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000102

Phillips JT, Brown SR, Mitchell P, Shorthouse AJ (2006) Anaerobic meningitis secondary to a rectothecal fistula arising from an anterior sacral meningocele: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 49:1633–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0646-7

Quigley MR, Schinco F, Brown JT (1984) Anterior sacral meningocele with an unusual presentation. J Neurosurg 61:790–792

Raczynski RA, Fisher RG, Sass LA (2010) Unusual cases of meningitis as a clue to the diagnosis of Currarino syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 29(1):90

Sánchez AA, Iglesias CD, López CD, Cecilia DM, Gomez JA, Barbadillo JG, Pena SR (2008) Rectothecal fistula secondary to an anterior sacral meningocele. J Neurosurg Spine 8:487–489. https://doi.org/10.3171/SPI/2008/8/5/487

Schijman E, Rugilo C, Seviever G, Menendez R (2005) Anterior sacral meningocele. Child Nerv Syst 21:91–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-004-1086-0

Simon LG, Constantinescu A, Maftei AG, Popescu CD (2010) A particular evolution of Currarino syndrome. Eur J Neurol 17(Suppl. 3):319

Synowitz HJ, Lehmann R (1988) Meningitis as a complication of anterior-sacral meningocele. Zentralbl Neurochir 49(1):15–21

Tamayo JA, Arraez MA, Villegas I, Ruiz J, Rodriguez E, Fernandez O (1999) Partial Currarino syndrome in a non-pediatric patient. A rare cause of bacterial meningitis. Neurologia 14(9):460–462

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeltema, HR., Broens, P.M.A., Brouwer, O.F. et al. Severe bacterial meningitis due to an enterothecal fistula in a 6-year-old child with Currarino syndrome: evaluation of surgical strategy with review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 35, 1129–1136 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04138-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04138-8