Abstract

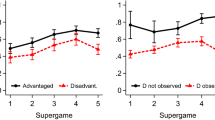

In this paper we experimentally investigate the relationship between inequality and conflicts, the latter taking the shape of rebellious actions. Further, our conflict experiment allows us to study whether lack of coordination or fear of retaliation may refrain individuals from rioting despite their willingness to riot. Our conflict game consists of two-stages. In a first stage, subjects play a proportional rent-seeking game to share a prize. In a second stage, players can coordinate with the other members of their group to reduce (“burn”) the other group members’ payoffs. Our treatments differ in the extent of inequality. Precisely, in the first series of treatments (called symmetric treatments), inequality only arises from different investment behaviors of players in the first stage. In a second series of treatments (called asymmetric treatments), inequality is strongly reinforced by attributing to some subjects (the advantaged group) a larger share of the price than other subjects (the disadvantaged group) for the same amount of effort. While the former refer to inequality of effort the latter is related to exogenous inequality of circumstances (bad luck). We ran these treatments under both partner and stranger matching protocol. Consistent with the assumption of inequality aversion, we observe that disadvantaged groups “burn” significantly more money than advantaged groups in the asymmetric treatment. However, we also observe that the relationship between inequality and conflicts is non-linear since the frequency of conflicts is significantly higher in the symmetric treatment where inequality is moderate compared to the asymmetric treatment where inequality is extreme. Resignation seems to be the main driving force behind this phenomenon. Our findings also shed light on the important role played by coordination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Cramer (2005) for the lineage of this idea from Aristotle and Plato through Montaigne and de Tocqueville to today’s academic debate.

Some have found positive relationships between income inequality and political violence (Muller and Seligson 1987; Midlarsky 1988; Brockett 1992; Binswanger et al. 1993; Alesina and Perotti 1996 provide examples). Others have found a negative relationship (Parvin 1973). Some researchers have tried to solve these apparent contradictions by suggesting a concave (inverted U-shaped) relationship. Political violence would occur most frequently at intermediate levels of economic inequality, less frequently at very low or very high levels. In a different setting, Robinson (2001) predicts this counter intuitive finding that ethnic conflict could be worse when the groups that engage in conflicts have roughly equal resources.

However, this literature recognizes that efforts themselves might well be endogenous too to exogenous circumstances. For instance, agents that are discriminated upon, say in the labour market, might not be incited to make efforts to find a job, if they think that it is not worthwhile.

Orthodox economic theory has long denied humans the desire to harm others without own benefit, but recent behavioural findings suggest that such a tendency does exist. Most of the behavioural economists have traditionally focused on situations in which humans are nicer than orthodox theory suggests, i.e. altruistic, fairness-driven, or reciprocal. The dark side of economic behaviour is only sparsely studied.

In a first treatment called full information, players are informed about their partner’s decision. In a second treatment, players can not exactly identify the partner’s action because a part of endowment can also be randomly destructed by Nature.

In our setting conflicts are costly with no monetary benefits although conflicts become less costly if all group members coordinate to engage together in conflict. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this remark.

It has been often argued that key feature of the mobile phones, particularly its flexibility and hyper-coordination helped coordination for collective expression.

In China, where political demonstrations are risky for participants, the New York Time reported that twelve thousand workers simultaneously went on strike in Shenzhen at the factory of a supplier of Wall Mart. The article mentions that coordination among the rioters was growing through the sending of coded messages to each other by cellphones (French 2004; Rheingold 2008). The New York Times also reported that mobile phones and web sites once again played a central role in the anti-Japanese demonstrations that broke out in several Chinese cities in April 2005. Neumayer and Stald (2013) shed light on the role of information provision through mobile communication in mass street protest based on two case studies the civic outrage of young people concerning the destruction of a youth centre in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2006 and the use of mobile phones in antifascist protests in Dresden, Germany in 2011. In the French case, the trigger for the French riots in fall 2005 was the accidental electrocution of two immigrant youths. It was claimed that these teenagers died while they were chased by the police, a charge the authorities denied. Tragic as this case was, it would usually not be sufficient as a cause of a rebellion of that scale. However, it served as a coordination device.

Following the terminology introduced in Roemer (1998), we refer to the former determinants as “circumstances”, which are exogenous to the person, such as family background while the latter factors correspond to “efforts” which can be influenced by the individual.

Esses et al. (1998) showed that competition for resources increases negative attitudes towards immigrants.

Hence, peer effects are modelled here in an induced value way by which the minority would follow the majority unless, otherwise, they accept to loose payoff. Breitmoser et al. (2014) model peer effects as induced value although without considering a coordination game.

Previous rent-seeking experiments have shown investments that are systematically above equilibrium levels. This possibility is excluded through our imposed restriction of the strategy space. In this study we are not interested in the behavioural properties of the rent-seeking game, but we rather use the game as a device to induce inequality of opportunities to study their effect on behaviour at the second stage. For that, it is actually desirable if subjects predictably reach the upper bound of the range, as it improves the comparability of observations.

These deliberations turned out to be empirically irrelevant, as in the experiment the focal equilibrium investment was reached very quickly (see next section).

Cooper et al. (1992) found, for instance, that subjects converge on the inefficient equilibrium when people interact with different opponents at each round. A reason generally evoked is that players are uncertain about which strategy will be played and favor the safe strategy (strategic uncertainty). Note that in our experiment, subjects are always matched with the same players within their group.

In this current study, we do not aim at disentangling these dimensions.

Indeed a very appealing hypothesis about distributional preference is inequality aversion (see Loewenstein et al. 1989; Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000; Charness and Rabin 2002; Falk et al. 2005). These approaches assume that individual utility depends not only on one’s own payoff but also on the equality of the income distribution.

We define a rioter here as someone who takes part in a brawl or a violent disturbance.

Other previous studies have investigated subjects’ reaction to the information on the opponents’ types. Some studies have also attempted to test whether subjects do act according to their stated beliefs or whether beliefs could be elicited without altering subjects’ behavior but empirical evidence is mixed. These studies are related to the growing literature on the level-k model that was developed in the recent two decades (see Crawford et al. 2013 for a detailed survey). In this current study we did not elicited beliefs. Testing how beliefs influence coordination is left for future research. For instance, using the strategy method may be a solution to isolate motives to riot induced by social preferences and those induced by expectations of others’ decisions.

There is no significant difference between first-stage payoffs for groups A and D in the sym treatments, suggesting the absence of framing effects.

In the statistical results of the tests reported here, the unit of observation is the session for the stranger treatments.

In additional estimates (available upon request) we checked whether D groups were more likely to fully coordinate (B,B,B) than the advantaged. For this purpose we ran an estimate at the group level on the probability that the group fully coordinates (BBBB). The dummy variable associated to the disadvantaged group captures a positive and highly significant coefficient indicating that D groups are more likely to fully coordinate on riots.

It is positive albeit non statistically significant in the partner symmetric treatment, however.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this helpful remark.

This approach is considered by the realistic conflict theory. It is also depicted in the typology of conflicts proposed by Katz (1965). Katz (1965) and more recently Fisher (2000) distinguish three main sources of conflicts, among which two sources rely on competition: economic conflicts that involve competition over scarce resources; Power conflicts that occur in case of competition for social domination. The last source of conflict is Value conflict that relies on disagreement between groups’ beliefs or lifestyles. Value conflicts are deliberately excluded from the analysis here. In the words of Fisher (2000), “groups not only fight over material goods but also for social status: each group seeks to maximize its domination in the relationship with the other. In other words, no one wants to be at the bottom, those at the bottom want to move up, while those at the top want to stay at the top.” This is also consistent with existing literature on patent racing. Indeed patent competition often has several of the characteristics of a race in which the largest prize is awarded to the first firm to make an industrial breakthrough that captures the largest share of industry profit (Grossman and Shapiro 1987) According to Shaver (2012) patent racing may sometime looks like a war. Shaver (2012) proposed a new model of “patent warfare” in which competing parties assemble strategic assets, then turn to battle their rivals for world domination.

In a related money burning experiment, Abbink et al. (2011) conducted a simple money-burning experiment in which the decider endowed with 50 tokens had to decide whether or not to reduce another person’s payoff at an own cost. The authors varied across tasks the endowment of the victim from 50 (the case in which there is no inequality) to 600, a case of extreme disadvantageous inequality. They observe that equal distributions (50,50) are particularly prone to destruction. Indeed the authors find that destruction rates are significantly higher in task (50,50) than in any of the other tasks. Charness and Grosskopf (2001) also observed evidence for desire for dominance. In one allocation task in Charness and Grosskopf (2001), a person could choose any amount between 300 and 1200 for the other person while receiving 600 for herself regardless of her choice. The authors find that a high number of people chose to allocate less than 600. One particularly eloquent example was the individual who chose 599 for the paired participant. Charness et al. (2011) investigate individuals’ investment in status in an environment where no monetary return can possibly be derived from reaching a better relative position. The authors find that even when wages are fixed, some people are willing to pay for status improvement without any instrumental monetary considerations, sacrificing money to potentially improve their rank. The authors also observe that individuals are more willing to do so when their performance is close to that of others, either to reach the highest rank or to avoid the lowest one. Consequently desire for dominance would be more likely to induce destruction for payoff distribution in which the payoffs across individuals (or groups) are close (Abbink et al. 2011).

We thank an anonymous referee for this helpful remark.

References

Abbink K, Brandts J (2009) Political autonomy and independence: theory and experimental evidence. Working Paper, University of Amsterdam

Abbink K, Hennig-Schmidt H (2006) Neutral versus loaded instructions in a bribery experiment. Exp Econ 9:103–121

Abbink K, Herrmann B (2011) The moral costs of nastiness. Econ Inq West Econ Assoc Int 49(2):631–633, 04

Abbink K, Sadrieh A (2009) The pleasure of being nasty. Econ Lett 105(3):306–308

Abbink K, Masclet D, van Veelen M (2011) Reference point effects in antisocial preferences. CIRANO Working Papers

Alesina A, Perotti R (1996) Income distribution, political instability, and investment. Eur Econ Rev 40(6):1203–1228

Alm J, McLelland GH, Schulze WD (1992) Why do people pay taxes? J Public Econ 48:21–38

Anderson CM, Putterman L (2006) Do non-strategic sanctions obey the law of demand? The demand for punishment in the voluntary contribution mechanism. Games Econ Behav 54(1):1–24

Arneson RJ (1989) Equality and equal opportunity of welfare. Philos Stud 56:77–93

Baldry JC (1986) Tax evasion is not a gamble—a report on two experiments. Econ Lett 22:333–335

Berninghaus SK, Ehrhart K-M (1998) Time horizon and equilibrium selection in tacit coordination games: experimental results. J Econ Behav Organ 37(2):231–248

Binswanger H, Deininger K, Feder G (1993) Power, distortions, revolt and reform in agricultural land relations. In: Behrman J, Srinivasan TN (eds) Handbook of development economics, vol 3. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam

Bolle F, Tan JHW, Zizzo DJ (2014) Vendettas. Am Econ J Microecon 6:93–130

Bolton GE, Ockenfels A (2000) ERC: a theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am Econ Rev 90:166–93

Bornstein G (1992) The free rider problem in intergroup conflicts over step-level and continuous public goods. J Personal Soc Psychol 62:597–606

Breitmoser Y, Tan JHW, Zizzo DJ (2014) On the beliefs of the path: equilibrium refinement due to quantal response and level-k. Games Econ Behav 86:102–125

Brockett CD (1992) Measuring political violence and land inequality in Central America. Am Polit Sci Rev 86(1):169–176

Burnham T, MCCabe K, Smith VL (2000) Friend- or foe: intentionality priming in an extensive form trust game. J Econ Behav Organ 43:57–74

Carpenter JP (2007) The demand for punishment. J Econ Behav Organ 62:522–542

Casari M (2005) On the design of peer punishment experiments. Exp Econ 8(2):107–115

Charness G, Grosskopf B (2001) Relative payoffs and happiness. J Econ Behav Organ 45(3):301–328

Charness G, Rabin M (2002) Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Q J Econ 117(3):817–869

Charness G, Masclet D, Villeval M-C (2011) Competitive preferences and status as an incentive: experimental evidence. CIRANO Working Papers 2011s-07, CIRANO

Clark K, Sefton M (2001) The sequential prisoner’s dilemma: evidence on reciprocation. Econ J 111:51–68

Cohen GA (1989) On the currency of egalitarian justice. Ethics 99:906–944

Collier P, Hoeffler A, Soderbom M (2004) On the duration of civil war. J Peace Res 41:253–73

Cooper R, DeJong D, Forsythe R, Ross T (1992) Communication in coordination games. Q J Econ 107(2):739–771

Cramer C (2005) Inequality and conflict–a review of an age-old concern. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Programme Paper 11

Crawford Vincent P, Costa-Gomes Miguel A, Iriberri N (2013) Structural models of nonequilibrium strategic thinking: theory, evidence, and applications. J Econ Lit 51(1):5–62

De Armond P (2000) Black flag over Seattle. Monitor A (ed) no. 72

Denant-Boemont L, Masclet D, Noussair C (2007) Punishment, counterpunishment and sanction enforcement in a social dilemma. Econ Theory 33(1):145–167

Dworkin R (1981) What is equality? Part I: equality of welfare. Philos Public Aff 10:185–246

Erev I, Bornstein G, Galili R (1993) Constructive intergroup competition as a solution to the free rider problem: a field experiment. J Exp Soc Psychol 29:463–478

Esses VM, Jackson LM, Armstrong T (1998) Intergroup competition and attitudes toward immigrants and immigration: an instrumental model of group conflict. J Soc Issues 54(4):699–724

Falk A, Fehr E, Fischbacher U (2005) Driving forces behind informal sanctions. Econometrica 73(6):2017–2030

Fehr E, Schmidt KM (1999) A theory of fairness, competition and cooperation. Q J Econ 114:817–68

Fisher RJ (2000) Intergroup conflict. In: Deutsch M, Coleman PT (eds) The handbook of conflict resolution: theory and practice. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, pp 166–184

Fleurbaey M (2008) Fairness, responsibility, and welfare. Oxford University Press, Oxford

French HW (2004) Workers demand union at WalMart supplier in China. The New York Times

Grossman G, Shapiro C (1987) Dynamic R&D competition. Econ J 97(372):387

Katz D (1965) Nationalism and strategies of international conflict resolution. In: Kelman HC (ed) International behavior: a social psychological analysis. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, pp 356–390

Kohli I, Singh N (1999) Rent seeking and rent setting with asymmetric effectiveness of lobbying. Public Choice 99(3):275–298

Loewenstein GF, Thompson L, Bazerman MH (1989) Social utility and decision making in interpersonal contexts. J Personal Soc Psychol 57:426–441

Midlarsky MI (1988) Rulers and the ruled: patterned inequality and the onset of mass political violence. Am Polit Sci Rev 82:491–509

Muller EN, Seligson MA (1987) Inequality and insurgency. Am Polit Sci Rev 81(2):425–452

Nagel J (1975) The descriptive analysis of power. Yale University Press, New Haven

Nagel JH (1976) Erratum. Word Politics 28(2):315

Neumayer C, Stald G (2013) The mobile phone in street protest: texting, tweeting, tracking, and tracing. Mob Media Commun 2(2):117–133

Nikiforakis N (2008) Punishment and counter-punishment in public good games: can we really govern ourselves? J Public Econ 92:91–112

Öncüler A, Croson R (2005) Rent-seeking for a risky rent a model and experimental investigation. J Theor Polit 17(4):403–429

Parvin M (1973) Economic determinants of political unrest. J Confl Resolut 17(2):271–296

Rheingold H (2008) Mobile media and political collective action. In: Katz J (ed) Handbook of mobile communication studies. The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp 225–240

Robinson JA (2001) Social identity, inequality and conflict. Econ Gov 2(1):85–99

Roemer J (1993) A pragmatic theory of responsibility for the egalitarian planner. Philos Public Aff 22:146–166

Roemer J (1998) Equality of opportunity. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Roemer JE, Trannoy A (2016) Equality of opportunity: theory and measurement. J Econ Lit 54(4):1288–1332

Rustichini A (2008) Dominance and competition. J Eur Econ Assoc 6(2–3):647–656

Sen A (1992) Inequality reexamined. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Shaver L (2012) Illuminating innovation: from patent racing to patent war. Wash Lee Law Rev 69(4):1891–1947

Stewart F (2002) Horizontal inequalities: a neglected dimension of development. QEH Working Paper Series, Working Paper Number 81

Tadjoeddin MZ, Suharyo WI, Mishra S (2003) Aspiration to inequality: regional disparity and centre-regional conflicts in Indonesia. UNI/WIDER Project Conference on Spatial Inequality in Asia

Tan JHW, Bolle F (2007) Team competition and the public goods game. Econ Lett 96:133–139

Van Huyck JB, Battalio RC, Beil RO (1990) Tacit coordination games, strategic uncertainty, and coordination failure. Am Econ Rev 80(1):234–48

Weede E (1981) Income inequality, average income, and domestic violence. J Confl Resolut 25:639–654

Zizzo DJ (2003) Money burning and rank egalitarianism with random dictators. Econ Lett 81:263–266

Zizzo DJ, Oswald AJ (2001) Are people willing to pay to reduce others’ incomes? Annales d’Economie et de Statistique 63(64):39–65

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Elven for programming the experiment. We are grateful to seminar participants in Amsterdam, Norwich, Caen, Paris, Pasadena and Prague for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Jordi Brandts, David Dickinson, Catherine Eckel, Dirk Engelman, Enrique Fatas, Charles Figuieres, Ragan Petrie, Marc Willinger and Marie-Claire Villeval, Daniel Zizzo and all the participants at the Conflict Experiment Workshop in Rennes, France. Financial support from the Agence Nationale de Recherche (ANR) through the project “GTCI Guerre, terrorisme et commerce international” and ANR-08-JCJC-0105-01, “CONFLICT” project are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Instructions (asym treatment)

1.1.1 General instructions

You are now taking part in an economic experiment of decision making. The instructions are simple. If you read the following instructions carefully, you can, depending on your decisions and the decisions of others, earn a considerable amount of money. It is therefore very important that you read these instructions with care.

The instructions we have distributed to you are solely for your private information. It is prohibited to communicate with the other participants during the experiment. Should you have any questions please ask us. If you violate this rule, we shall have to exclude you from the experiment and from all payments.

Each participant receives a lump sum payment of 3 € at the beginning of the experiment. At the end of the experiment your entire earnings from the experiment will be immediately paid to you in cash. During the experiment your entire earnings will be calculated in points. At the end of the experiment the total amount of points you have earned will be converted to euro at the following rate:

At the beginning of the experiment, you will be assigned a role of player A or player B. You will keep your role during the entire experience. The participants will be then assigned to a group of six which is composed of three players of type A and three players of type B. You will therefore be in interaction with 3 other participants. If you are player A, then you are matched with three players B and two player A, and reversely. The composition of the groups remains unchanged during the experience.

The experiment is divided into twenty periods. The instructions for each period are given in the detailed instructions.

1.2 Detailed instructions

1.2.1 Each period consists of two stages

First stage In this stage, you and the 5 other participants in your group will have to share a monetary prize of 576 points. The share of the 576 points you receive depends on your decision and the decisions of the five other participants in your group.

You can affect your share of the prize by purchasing tickets. Your share of the prize in your group also depends on the number of tickets purchased by the three other participants in your group. More precisely, the prize is divided among the participants in amounts to the number of tickets they purchase. However, for the same number of tickets bought, players A will receive 4 times more amount of the prize than players B. After your decision about how many tickets you wish to purchase, you will be able to observe the number of tickets the other participants purchase.

At the beginning of first stage of each period, each participant will get an endowment of 100 points. You can keep as much of this 100 points as you like, or you can use some of it to purchase tickets. Note that you cannot buy more than 80 tickets. Each ticket will cost you 1 point.

In your group, each participant’s share, or proportion, of the 576 prize will be given by the number of tickets they purchased divided by the total number of tickets purchased in their four participant group.

Your earning in this decision will be the part of you endowment of 100 point which you do not spend on tickets, plus the share of the 576 prize you receive. To summarize, your earnings for this first stage at each period will be calculated:

Example Suppose for example that you are player A1 and you buy 30 lottery tickets, player A2 buys 60 tickets, player A3 buys 0 tickets, players B1, B2 and B3 buy 10, 50 and 0 tickets, respectively. The share of the price you receive equals \(4 \times 30/(4 \times 30+4\times 60+10+50)=6/24=2/7\). Your earnings for this first stage at each period will be \(100+576\times 2/7-30=234.\)

The second stage At the beginning of the second stage, your screen shows you the income of each of the six group members (including your own income) as well as their type (A or B).

In this stage you have the opportunity to coordinate with the participant of your type (your co-player) in order to reduce or leave equal the income of each group member of the other type. For example, if you are a player A, you can coordinate with the two other players A to reduce the income of each other player of type B, and reversely. To simplify we will call Reduce the decision consisting in reducing the payoff of the other group and Not Reduce, the decision consisting in not reducing the payoff of the other group. If you and your co player coordinate choose to reduce the income, then the income of each member of the other type will be reduced of 40 points. On the contrary, the income of each member of the other group remains unchanged. You will also incur a cost in points which depend on your decision and the decision of your co-player. If you chooses to not to Reduce and that this decision is chosen at the majority, then your incur no cost. The income of the other group members remain unchanged. If you choose Not Reduce while the majority of your group chooses Reduce, you incur a cost of −10 and the income of each other player of thee other type is reduced of 40 points. If you choose to reduce and if this decision is chosen at the majority, then you incur a cost of −5. Finally, if you choose to reduce while the majority of your group chooses not to reduce, then, you incur a cost of −20. To summarize, your second-stage payoff table is:

Your decision | Choice of your first co-player | Choice of your second co-player | Cost for the other group | Cost for your decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

R | R | R | \(-\)40 | \(-\)5 |

R | R | NR | \(-\)40 | \(-\)5 |

R | NR | NR | 0 | \(-\)20 |

NR | R | R | \(-\)40 | \(-\)10 |

NR | NR | R | 0 | 0 |

NR | NR | NR | 0 | 0 |

All players have exactly the same payoff table.

After having taken your decision of reducing or not (the income of the other group), you must press the ok button. Once you have done this, your decision can no longer be revised. When you make your decision you will not know the decision of the other participants. After all members of your group have made their decision, the computer will record the decisions of all participants and will inform you of:

-

the global decision taken by your group: reduction or not of the income of each member of the other group

-

the global decision taken by the other group: reduction or not of the income of each member of your group (including yourself).

At the end of the period, the computer will calculate your income of second stage that also corresponds to your final income for each period. Your total income from the two stages is therefore calculated as follows:

Example 2 Suppose you are player B1 and you choose Reduce. Suppose also that players B2 and B3 also chose Reduce. In this case, since all group member chose Reduce, then the global decision of your group is Reduce. Therefore, the income of players A1, A2 and A3 will be reduced of 40 points. You will incur a cost for your activity of reduction of −5 points (Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abbink, K., Masclet, D. & Mirza, D. Inequality and inter-group conflicts: experimental evidence. Soc Choice Welf 50, 387–423 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-017-1089-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-017-1089-x