Abstract

The island of Cyprus has a long history of human impacts, including the introduction of more than 250 plant species. One of these introduced species is Juglans regia (walnut), which is considered a naturalised non-native (introduced in last 500 years). Here we report the earliest occurrence of Juglans regia pollen grains from a sedimentary deposit on Cyprus. The pollen recovered from the Akrotiri Marsh provides an earliest introduction date of 3,100-3,000 cal yr bp. This Bronze Age occurrence of Juglans regia is sporadic. However, by 2,000 cal yr bp the pollen signal becomes more persistent and indicates that introduction or expansion of Juglans regia was highly likely in the Roman period. We integrate our new results with younger pollen occurrences of Juglans regia on Cyprus, the archaeobotanical record and documentary evidence to provide an overview of this archaeophyte. Our findings show that, following the conventions of the Flora of Cyprus, Juglans regia should be reclassified from naturalised non-native to indigenous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The island of Cyprus is the third largest island in the Mediterranean, with diverse topography and a Mediterranean climate of hot, dry summers and relatively mild, moist winters (Delipetrou et al. 2008; Fall 2012). This unique combination means the island has a diverse flora within the Mediterranean biodiversity hotspot (Médail and Quézel 1999; Hand et al. 2019). The Flora of Cyprus contains 1,946 recorded taxa with 8.55% of these being endemic to the island, making it an important biodiversity hotspot within the Mediterranean basin (Médail and Quézel 1999; Hand et al. 2011, 2019). Due to a long history of human interaction with the landscape, the list also contains 254 naturalised and casual taxa (Hand et al. 2019).

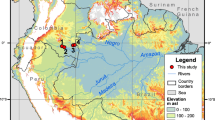

One of these naturalised non-native taxa is Juglans regia, which is found in phytogeographical zone 2 of Cyprus, the Troodos Mountains (Hand et al. 2011; Fig. 1). Within Europe, the geographical distribution of Juglans regia has been heavily influenced by anthropogenic activity (Pollegioni et al. 2017). At the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, Juglans regia inhabited refugia across southern Europe and Anatolia (Bottema 1980, 2000; Pollegioni et al. 2017). Genetic admixture between these refugia populations began in the Bronze Age and is coeval with increases in Juglans pollen within palaeoenvironmental archives of the Balkans, Levant and Anatolia (Bottema 1980, 2000; Eastwood et al. 1998; Izdebski et al. 2016). The increase in Juglans pollen is part of a wider assemblage indicating human impacts on the environment associated with increased agriculture and arboriculture (Eastwood et al. 1998; Woodbridge et al. 2019). Termed the Beyşehir Occupation Phase (3,500-1,350 bp), it has also been observed in the wider region, including the Caucasus, Georgia and Iran (Izdebski et al. 2016), leading to the proposal that this might represent a degree of homogenisation in agricultural practices, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman empires (Izdebski et al. 2016).

The island of Cyprus showing the seven phytogeographical zones, major settlements, palaeoenvironmental records and archaeological sites with Juglans pollen or Roman – Byzantine archaeobotanical remains. Phytogeographical zone 2 (Troodos Mountains), where Juglans regia is mainly found today, is highlighted in yellow. Phytogeographical divisions follow Meikle (1977, 1985) and Hand et al. (2011)

When Juglans regia came to Cyprus is largely unknown. Izdebski et al. (2016) attributed Juglans pollen from the Larnaca Salt Lake to the Beyşehir Occupation Phase. However, Juglans is not present in this record until the Byzantine period – after the traditional dates for the Beyşehir Occupation Phase (Kaniewski et al. 2013). In this study we report the earliest occurrence of Juglans regia pollen in a palaeoenvironmental setting from southern Cyprus, provide an introduction date for this naturalised non-native species and link the palaeoenvironmental records to archaeological and historical occurrences of Juglans regia.

Methods

Six sediment cores were taken from the Akrotiri Marsh, a freshwater marsh located on the Akrotiri Peninsula that is part of the Akrotiri Wetlands Special Protection Area (Kassinis and Charalambidou 2021) on the south of the Island of Cyprus (Fig. 1). Pollen samples were treated with potassium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, hydrofluoric acid and acetolysis before being mounted in silicon oil. Pollen concentration was determined using Lycopodium clavatum marker spores (Riding 2021). Chronological control comes from six radiocarbon dates (Hazell et al. 2022). Full details of the methodology, core sedimentology, details of radiocarbon dates, diatom results and pollen diagrams are available in Hazell et al. (2022). In this paper, we report Juglans regia pollen and the pollen concentration record from two cores AM18-1 and AM18-5 from the Akrotiri Marsh.

Results

Juglans regia pollen is first present in the Akrotiri Marsh sedimentary record at 3,010 cal yr bp (AM18-5) and 3,100 cal yr bp (AM18-1) (Fig. 2). This earliest presence is greater in core AM18-1 at 2.3% of the total pollen amount, however the overall pollen concentration is also substantially higher in this core at this time (Fig. 2). Following this first occurrence in both cores, the abundance of Juglans regia in AM18-1 is low and sporadic for the remainder of the record (Fig. 2). In AM18-5, Juglans regia pollen is also sporadically present until 2,000 cal yr bp, after which the record becomes more constant and fluctuates between 1 and 4% until the end of this core at 1,380 cal yr bp (Fig. 2). These fluctuations in the Juglans regia record in core AM18-5 occur in tandem with the pollen concentration of the sediments. A final occurrence of Juglans regia pollen at 1,000 cal yr bp is found in core AM18-1. As both records show older peaks in pollen concentration without the presence of Juglans regia, the earliest occurrence in the Akrotiri Marsh is 3,100-3,010 cal yr bp (Fig. 2).

The chronological distribution of Juglans pollen on Cyprus, pollen concentration values in the Akrotiri Marsh records and key pre-historical and historical events relating to Juglans on Cyprus and in the wider eastern Mediterranean region. (1) Kearns and Manning (2019); (2) Kaniewski et al. (2013); (3) Harris (2007); (4) Lardos (2006); (5) Rautmann (2003); (6) Jouffroy-Bapicot et al. (2016); (7) Douché et al. (2021); (8) Langgut et al. (2013); (9) Eastwood et al. (1998); (10) Bell (2012); 11) Broodbank (2013);12) Langgut (2015); 13) Benzaquen et al. (2019)

Discussion

Previously the earliest known presence of Juglans regia in a sedimentary archive on Cyprus was 840 cal yr bp (Fig. 2) from the Larnaca Salt Lake (Kaniewski et al. 2013). The Akrotiri Marsh record has an earliest occurrence during the Bronze Age: ca. 3,000 cal yr bp (Fig. 2). Bottema (1980) proposed Juglans was introduced to southeast Europe (Greece) at around 3,500 bp and it is considered part of the Beyşehir Occupancy Phase agroforestry signal in pollen data (Izdebski et al. 2016). Although more recent genetic work suggests it could have had diverse refugia across much of Eurasia between 30–45°N, but not Cyprus (Aradhya et al. 2017). The earliest dates of Juglans regia in the Akrotiri Marsh are consistent with a Beyşehir Occupation Phase introduction during the Bronze Age (Fig. 2, Izdebski et al. 2016). An increase in tree crops, at the expense of grain production, during the Bronze Age has been previously proposed and linked to engagement in wider trade networks in the Eastern Mediterranean (Lucas and Fuller 2020). However, Juglans remains have not been reported from Bronze Age archaeological sites on Cyprus (Lucas 2014; Lucas and Fuller 2020).

A combined study of ethnolinguistics and genetics suggested a spread of Juglans from the Early Bronze Age, driven by Greek, Roman and Persian expansion/trading (Pollegioni et al. 2020). The persistent presence of Juglans pollen from around 2,000 cal yr bp in AM18-5 would be consistent with a Roman expansion of walnut on Cyprus (Fig. 2). It was a luxury Roman commodity in Central Europe with archaeobotanical remains appearing in 72 archaeological sites (Bakels and Jacomet 2003). As well as being a food throughout the Roman world (Rowan 2019), the nuts had symbolic meaning at marriages and burials (Reed et al. 2019), young fruits were used for hair dye (Pliny the Elder), trees were used for timber (Allevato et al. 2009) and the plant was grown in gardens (Langgut 2022). Textual evidence from Greek, Roman and Jewish sources also testifies to widespread Juglans regia cultivation throughout the Mediterranean at this time (Zohary et al. 2012); this is also attested by archaeobotanical and palynological remains from Roman Petra, Jordan (Bouchaud et al. 2017) and Salagassos, Turkey (Baeten et al. 2012). In the Akrotiri Marsh, the largest and most persistent presence of Juglans pollen comes during the Roman archaeological periods on Cyprus (Fig. 2). Archaeobotanical remains from Cyprus that post-date the Bronze Age are not common and even from earlier periods the island is considered to have an under-investigated botanical record (Butzer and Harris 2007; Falconer and Fall 2013; Lucas 2014; Kofel et al. 2021). Returning to the Roman periods, the Earthquake House (1,700-1,585 year bp) at nearby Kourion (Fig. 1) has a limited archaeobotanical record, but no Juglans reported (Soren et al. 1986). Charcoal found in Roman slag heaps dating from 1,980 to 1,300 cal yr bp in Skouriotissa Vouppes and Ayia Marina Mavrovouni contain only local tree taxa (Given et al. 2013). Juglans is reported from the Late Roman – Byzantine site of Kalavasos-Kopetra dated to 1,350-1,280 year bp (Rautman 2003). These archaeobotanical finds dated to the end of the AM18-5 record (Fig. 2) come from both residential and ecclesiastical settings (Rautman 2003). Whilst this provides some archaeobotanical support to our record, it is important to consider that these might also have been imported. Walnuts have been reported from shipwrecks from Roman Portus (near Rome) in Italy (Parker 1992) and the Byzantine port of Caesarea Maritima, Israel (Ramsay 2010).

The sedimentology of the Akrotiri Marsh changes at around 1,500 cal yr bp from peat/organic rich clay to a red-brown clayey silt. This is accompanied by a change in the diatom and pollen assemblages (Hazell et al. 2022). This sedimentology change leads to a barren record in the upper 20 cm of AM18-5, but Juglans pollen is present at 1,000 cal yr bp in AM18-1 (Fig. 2). Following this last occurrence in the Akrotiri Marsh, Juglans pollen is reported from the Larnaca Salt Lake from 840 − 690 cal yr bp (Kaniewski et al. 2013). This youngest occurrence could be linked with continued walnut arboriculture on the island for food and timber and an increase in church and monastery construction (Butzer and Harris 2007). Walnuts were mentioned as a medicinal ingredient in the Iatrosophikon (written in 1849) from a monastery founded in the 12th century ad (Lardos 2006). Other documentary evidence also demonstrates a continued presence of walnut on Cyprus. Dummond, in the mid-1700s, reported seeing Juglans on Cyprus (Harris 2007) and an Ottoman property register from 1833 reported Juglans growing in a number of settlements from 300 to 700 m above sea level (a.s.l.) (Given and Hadjianastasis 2010). Thomson (1879) mentioned walnuts from Levka (inland from Morphou Bay) a settlement at around 200 m a.s.l., but did not state whether he saw the trees. Writing in the 20th century, Haji-Costa and Percival (1944) mentioned the quality of walnuts coming from the Pitsilia region in the Troodos Mountains (around 1,000 m a.s.l.). Using these historical observations as estimates of where Juglans could have grown, altitudes of 300 m and above are found 8–10 km from the Akrotiri Marsh in the lower slopes of Troodos Mountains and along the Kouris River.

Juglans pollen is not abundant in the palaeoenvironmental records of Cyprus, but this is not surprising as it is not well represented in pollen rain studies due to a low dispersal potential. Juglans pollen is typically under-represented in extra-local and regional pollen rain due to low pollen production for an anemophilous taxon and fall speed combining to make it an unlikely long-distance contaminant (Bodmer 1922; Tormo Molina et al. 1996; Beer et al. 2007). Investigations from orchards of Juglans regia showed that the proportion of pollen recovered falls below 0.5% within metres of the orchard edge (Bottema 2000; Langgut 2015). On Cyprus, airfall samples from lowland Nicosia reach 0.48% (Gucel et al. 2013; Fall 2012) did not report the pollen from soil samples even when trees were present in the study site. Bottema (2000) considered that pollen percentages of Juglans above 2% indicated a number of trees in the nearby vicinity. Using this indicator value would suggest the presence of Juglans trees in the vicinity of the Akrotiri Marsh (Fig. 2). Alternatively, material could have been washed in from the nearby Kouris River and originally have been from the Troodos Mountains.

A Bronze Age to Roman period spread of Juglans has been proposed from palynological, ethnolinguistic and genetic studies (Bottema 1980, 2000; Eastwood et al. 1998; Pollegioni et al. 2017, 2020). Genetics show refugia in southern Europe and Anatolia, which provides a starting point to consider how this important economic species spread (Pollegioni et al. 2017, 2020). In the Levant, pollen and charcoal evidence are first reported from Israel dating to before 3,500 year bp (Fig. 2). Walnuts, as a commodity, are mentioned in the private archive of the merchant Yabninu from Ugarit (present-day Syria), who was involved in an extensive trade network across the eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus, from 3,210 to 3,185 year bp (Bell 2012; Broodbank 2013). Both of these overlap with the earliest portion of the Beyşehir Occupancy Phase in Anatolia and might show an early period of walnut trade and, in the case of evidence from Israel and Cyprus, potentially early arboriculture (Fig. 2). The growing of Juglans in Israel is also evidenced from the Royal Persian Garden (at least 2,400 year bp) at Ramat Rahel (Langgut et al. 2013). Archaeobotanical studies from Greece show the presence of walnuts in sites dating to the Classical and Hellenistic periods (ca. 2,500-2,030 year bp) (Douché et al. 2021). On the island of Crete, Juglans pollen is first recorded from 1,900 cal yr bp (Jouffroy-Bapicot et al. 2016), a comparable date to the more constant presence in our AM18-5 record (Fig. 2). Combining these records would imply a spread out of refugia and into the Levant, perhaps through Bronze Age trading networks, and a spread through Greece after the Bronze Age and onto Crete following the Roman conquest.

Where Cyprus sits in this possible pattern is less clear. Using the earlier dates would imply a Late Bronze Age introduction (Fig. 2), whilst climate change during this interval might have made this challenging and potentially a failed arboriculture experiment (Hazell et al. 2022). In the mid-20th Century, walnuts were grown along watercourses or in places with irrigation in Cyprus (Christodoulou 1959); it is likely then that any period of aridity would adversely affect Juglans orchards. On Cyprus a peak in aridity is recorded at 2,800 cal yr bp (Kaniewski et al. 2020; Hazell et al. 2022), when the Juglans pollen disappears from the AM18-1 record (Fig. 2). A return of Juglans pollen at around 2,000 cal yr bp in AM18-5, also corresponds to an interval of greater water availability recorded in both the Akrotiri Marsh (Hazell et al. 2022) and higher winter precipitation recorded at Hala Sultan Teke (Kaniewski et al. 2020). The precise role that ambient climate played in the establishment of Juglans on Cyprus is speculative, but the current palaeoclimate records from the island do not show any major aridity peaks (comparable to those in the Late Bronze Age) over the last 2,000 years in which Juglans has been present on the island.

Pollen evidence from well-dated palaeoenvironmental archives suggests that Juglans regia has been present on Cyprus since ca. 3,000 cal yr bp (Fig. 2). Additional evidence comes from the Akrotiri Borehole 2 (Fig. 1), which was taken from the Akrotiri (Limassol) Salt Lake (Allen et al. 2009). Here, Juglans pollen is present in low percentages at 160–180 cm depth. However, only a single radiocarbon date from 453 cm depth provides chronological context, showing the Juglans presence here to be younger than 6,890-6,640 cal yr bp (Allen et al. 2009). From an archaeological context, low amounts of Juglans pollen were reported in “Colonne 5bis” from Khirokitia (Fig. 1) in horizon D, with a recently recalibrated date for this occurrence of 6,590 ± 260 cal yr bp (Renault-Miskovsky 1989; Knapp 2013). At Kirokitia, it was suggested that Juglandaceae pollen (including Carya) could have been reworked from pre-Quaternary sediments (Renault-Miskovsky 1989). However, Juglandaceae pollen has not yet been reported from the limited palynology conducted on pre-Quaternary sedimentary rocks on Cyprus (Rouchy et al. 2001; Athanasiou et al. 2021). These tantalising data might attest to an earlier presence of small amounts of Juglans regia on Cyprus, but this is pure speculation without longer and older palaeoenvironmental records from phytogeographical zone 2 (Fig. 1).

Conclusions

Combined pollen records from the south coast of Cyprus show that Juglans regia has been present on the island of Cyprus for 2,000–3,100 years. Sporadic pollen occurrences during the Bronze Age could point to an introduction during this period and are consistent with findings from around the eastern Mediterranean. An increase in proportion and frequency of occurrence during the Roman period means that this would be a conservative introduction date. This conservative introduction date would be consistent with widespread Roman arboriculture aimed at nut and timber production. In the context of present day Cyprus, this would change the status of Juglans regia from a naturalised non-native species to an indigenous species.

References

Allen MJ, Scaife R, Manning A, Edwards RJ (2009) The development and vegetation history of the Akrotiri Salt Lake. Cyprus Quat Newsl 119:1–15

Allevato E, Ermolli ER, di Pasquale G (2009) Woodland exploitation and Roman shipbuilding. Preliminary data from the shipwreck Napoli C (Naples, Italy). J Mediterr Geogr 112:33–42

Aradhya M, Velasco D, Ibrahimov Z et al (2017) Genetic and ecological insights into glacial refugia of walnut (Juglans regia L.). PLoS ONE 12:e0185974

Athanasiou M, Triantaphyllou MV, Dimiza MD et al (2021) Reconstruction of oceanographic and environmental conditions in the eastern Mediterranean (Kottafi Hill section, Cyprus Island) during the middle Miocene Climate Transition. Rev Micropaléontol 70:100480

Baeten J, Marinova E, De Laet V, Degryse P, De Vos D, Waelkens M (2012) Faecal biomarker and archaeobotanical analyses of sediments from a public latrine shed new light on ruralisation in Sagalassos, Turkey. J Archaeol Sci 39:1,143–1,159

Bakels C, Jacomet S (2003) Access to luxury foods in Central Europe during the Roman period: the archaeobotanical evidence. World Archaeol 34:542–557

Beer R, Tinner W, Carraro G, Grisa E (2007) Pollen representation in surface samples of the Juniperus, Picea and Juglans forest belts of Kyrgyzstan, central Asia. Holocene 17:599–611

Bell C (2012) The merchants of Ugarit: oligarchs of the Late Bronze Age trade in metals? In: Kassianidou V, Papasavvas G (eds) Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 180–187

Benzaquen M, Finkelstein I, Langgut D (2019) Vegetation History and Human Impact on the Environs of Tel Megiddo in the Bronze and Iron Ages: A Dendroarchaeological Analysis. Tel Aviv 46:42–64

Bodmer H (1922) Über den Windpollen. Natur und Technik 3:294–298

Bottema S (1980) On the history of the walnut (Juglans regia L.) in southeastern Europe. Acta Bot Neerl 29:343–349

Bottema S (2000) The Holocene history of walnut, sweet-chestnut, manna-ash and plane tree in the Eastern Mediterranean. Pallas 52:35–59

Bouchaud C, Jacquat C, Martinoli D (2017) Landscape use and fruit cultivation in Petra (Jordan) from Early Nabataean to Byzantine times (2nd century BC–5th century ad). Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:223–244

Broodbank C (2013) The making of the Middle Sea: a history of the Mediterranean from the beginning to the emergence of the classical world. Thames & Hudson, London

Butzer KW, Harris SE(2007) Geoarchaeological approaches to the environmental history of Cyprus: explication and critical evaluation.J Archaeol Sci 34:1,932–1,952

Christodoulou D (1959) The evolution of the rural land use pattern in Cyprus. The World Land Use Survey Monograph 2: Cyprus. Geographical Publications, Bude

Delipetrou P, Makhzoumi J, Dimopoulos P, Georghiou K (2008) Cyprus. In: Vogiatzakis I, Pungetti G, Mannion AM (eds) Mediterranean Island Landscapes: Natural and Cultural Approaches. Springer, Berlin, pp 170–203

Douché C, Tsirtsi K, Margaritis E (2021) What’s new during the first millennium BCE in Greece? Archaeobotanical results from Olynthos and Sikyon. J Archaeol Sci: Rep 36:102782

Eastwood WJ, Roberts N, Lamb HF (1998) Palaeoecological and archaeological evidence for human occupance in southwest Turkey: The Beyşehir occupation phase. Anatol Stud 48:69–86

Falconer SE, Fall PL (2013) Household and community behavior at Bronze Age Politiko-Troullia, Cyprus. J Field Archaeol 38:101–119

Fall PL (2012) Modern vegetation, pollen and climate relationships on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 185:79–92

Given M, Hadjianastasis M (2010) Landholding and landscape in Ottoman Cyprus. Byzantine Mod Greek Stud 34:38–60

Given M, Knapp AB, Noller J, Sollars L, Kassianidou V (2013) Landscape and Interaction: The Troodos Archaeological and Environmental Research Project, Cyprus. The TAESP Landscape. Levant Supplementary Series 15, vol 2. Oxbow Books, Oxford

Gucel S, Guvensen A, Ozturk M, Celik A (2013) Analysis of airborne pollen fall in Nicosia (Cyprus). Environ Monit Assess 185:157–169

Haji-Costa I, Percival DA (1944) Some Traditional Customs of the People of Cyprus. Folklore 55:107–117

Hand R, Hadjikyriakou GN, Christodoulou CS (eds) (2011) Flora of Cyprus – a dynamic checklist. https://www.flora-of-cyprus.eu/. Accessed 10 September 2021 (continuously updated)

Hand R, Hadjikyriakou GN, Christodoulou CS (2019) Updated numbers of the vascular flora of Cyprus including the endemism rate. Cypricola 13:1–6

Harris SE (2007) Colonial forestry and environmental history: British policies in Cyprus, 1878–1960. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin

Hazell CJ, Pound MJ, Hocking EP (2022) Response of the Akrotiri Marsh, island of Cyprus, to Bronze Age climate change. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 587:110788

Izdebski A, Pickett J, Roberts N, Waliszewski T (2016) The environmental, archaeological and historical evidence for regional climatic changes and their societal impacts in the Eastern Mediterranean in Late Antiquity. Quat Sci Rev 136:189–208

Jouffroy-Bapicot I, Vannière B, Iglesias V, Debret M, Delarras J-F (2016) 2000 years of grazing history and the making of the Cretan mountain landscape, Greece. PLoS ONE 11:e0156875

Kaniewski D, Van Campo E, Guiot J, Le Burel S, Otto T, Baeteman C (2013) Environmental roots of the Late Bronze Age crisis. PLoS ONE 8:e71004

Kaniewski D, Marriner N, Cheddadi R, Fischer PM, Otto T, Luce F, van Campo E (2020) Climate change and social unrest: A 6,000-year chronicle from the eastern Mediterranean. Geophys Res Lett 47:e2020GL087496

Kassinis N, Charalambidou I (2021) Autumn migration of the Red-footed Falcon, Falco vespertinus, at Akrotiri Peninsula, Cyprus 2009–2019 (Aves: Falconiformes). Zool Middle East 67:19–24

Kearns C, Manning SW (2019) New Directions in Cypriot Archaeology. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Knapp AB (2013) The Archaeology of Cyprus: From earliest Prehistory to the Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kofel D, Bürge T, Fischer PM (2021) Crops and food choices at the Late Bronze Age city of Hala Sultan Tekke. J Archaeol Sci: Rep 36:102827

Langgut D (2015) Prestigious fruit trees in ancient Israel: first palynological evidence for growing Juglans regia and Citrus medica. Isr J Plant Sci 62:98–110

Langgut D (2022) Prestigious Early Roman gardens across the Empire: The significance of gardens and horticultural trends evidenced by pollen. Palynology https://doi.org/10.1080/01916122.2022.2089928

Langgut D, Gadot Y, Porat N, Lipschits O (2013) Fossil pollen reveals the secrets of the Royal Persian Garden at Ramat Rahel. Jerus Palynology 37:115–129

Lardos A (2006) The botanical materia medica of the Iatrosophikon—A collection of prescriptions from a monastery in Cyprus. J Ethnopharmacol 104:387–406

Lucas L (2014) Crops, Culture, and Contact in Prehistoric Cyprus. BAR International Series, vol 2639. Archaeopress, Oxford

Lucas L, Fuller DQ (2020) Against the Grain: Long-Term Patterns in Agricultural Production in Prehistoric Cyprus. J World Prehist 33:233–266

Médail F, Quézel P(1999) Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: Setting global conservation priorities. Conserv Biol 13:1,510–1,513

Meikle RD (1977) Flora of Cyprus 1. Bentham-Moxon Trust. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Meikle RD (1985) Flora of Cyprus 2. Bentham-Moxon Trust, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Parker AJ (1992) Ancient shipwrecks of the Mediterranean and the Roman Provinces. BAR International Series 580. BAR Publishing, Oxford

Pliny the Elder (translated by Bostock J, Riley HT (1855) Pliny the Elder: The Natural History. Taylor and Francis, London. Perseus Digital Library. http://data.perseus.org/citations/urn:cts:latinLit:phi0978.phi001.perseus-eng1:15.24. Accessed 25 June 2022

Pollegioni P, Del Lungo S, Müller R et al(2020) Biocultural diversity of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) and sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) across Eurasia. Ecol Evol 10:11,192–11,216

Pollegioni P, Woeste K, Chiocchini F et al (2017) Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. PLoS ONE 12:e0172541

Ramsay J (2010) Trade or Trash: an examination of the archaeobotanical remains from the Byzantine harbour at Caesarea Maritima, Israel. Int J Naut Archaeol 39:376–382

Rautman M(2003) A Cypriot Village of Late Antiquity: Kalavasos-Kopetra in the Upper Vasilikos Valley. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 52. JRA, Portsmouth

Reed K, Lodwick L, Leleković T, Vulić H (2019) Exploring Roman ritual behaviours through plant remains from Pannonia Inferior. Environ Archaeol 24:28–37

Renault-Miskovsky J (1989) Etude Paleobotanique, Paleoclimatique et Paleoethnographique du Site Neolithique de Khirokitia a Chyphre: Rapport de la Palynologie. In: Le Brun A (ed) Fouilles Recentes a Khirokitia (Chypre) 1983–1986. Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations, Paris, pp 151–163

Riding JB (2021) A guide to preparation protocols in palynology. Palynology 45 (Suppl 1):1–110

Rouchy JM, Orszag-Sperber F, Blanc-Valleron M-M, Pierre C, Rivière M, Combourieu-Nebout N, Panayides I (2001) Paleoenvironmental changes at the Messinian–Pliocene boundary in the eastern Mediterranean (southern Cyprus basins): significance of the Messinian Lago-Mare. Sediment Geol 145:93–117

Rowan E (2019) Same Taste, Different Place: Looking at the Consciousness of Food Origins in the Roman World. Theor Roman Archaeol J 2:1–18

Soren D, Gardiner R, Davis TH(1986) Archaeobotanical Research. Report of the Department of Antiquities Cyprus 1986:206

Thomson J (1879) A Journey through Cyprus in the Autumn of 1878. Proc R Geogr Soc Month Rec Geogr 1:97–105

Tormo Molina R, Muñoz Rodríguez A, Silva Palaciso I, Gallardo López F (1996) Pollen production in anemophilous trees. Grana 35:38–46

Woodbridge J, Roberts CN, Palmisano A et al (2019) Pollen-inferred regional vegetation patterns and demographic change in Southern Anatolia through the Holocene. Holocene 29:728–741

Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E (2012) Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of domesticated plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to Chris Hadjigeorgiou of the Geological Survey Department, Cyprus, Pantelis Charilaou of the Sovereign Base Area Administration Environmental Department, Thomas Hadjikyriakou of the Akrotiri Environmental Education and Information Centre, the Ministry of Defence and Defence Infrastructure Organisation for enabling us to undertake fieldwork and take samples. The fieldwork was kindly supported by a grant from the Council for British Research in the Levant and CJH thanks Northumbria University for funding his PhD studies. Lesley Dunlop, Dave Thomas and Will Thomas are thanked for their kind assistance in the lab. Ralf Hand and Charalambos Christodoulou are gratefully thanked for providing GIS layer files of the phytogeography of Cyprus. We thank T. Litt (editor) and an anonymous reviewer for their insightful comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The original pollen data from the Akrotiri Marsh were collected by CH. MP designed and drafted this paper in collaboration with CH and EH. All authors contributed to the writing, editing and figure design.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Litt.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pound, M.J., Hazell, C.J. & Hocking, E.P. The late Holocene introduction of Juglans regia (walnut) to Cyprus. Veget Hist Archaeobot 32, 125–131 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-022-00886-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-022-00886-x