Abstract

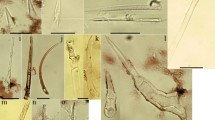

Non-woody plant remains are known from burial contexts in North–western Europe, but get overlooked when preservation is suboptimal. While phytolith analysis has demonstrated its value regarding the detection of vegetative grave goods, systematic application of this method to graves in European archaeology is, however, scarce. This paper concerns the examination of the elite Viking-Age equestrian burial at Fregerslev II, where phytolith analysis, combined with pollen analysis, revealed the presence of two types of plant material in the grave. The phytolith analysis of Fregerslev II included the investigation of chaff located close to a horse bridle, the chaff being both detected in the field and during investigation of a block sample by means of stereomicroscopy, and systematic examination of other parts of the grave to interpret this find. Elongate dendritic chaff phytoliths were subjected to systematic morphological and morphometric analysis and subsequent statistical analysis. The application of both methods simultaneously to large numbers of phytoliths is unique. Comparison of the various samples showed that the chaff represents a concentration of oat, which is most likely common oat, with minor admixture of barley, interpreted as horse fodder, while bedding consisting of hay or straw was presented elsewhere on the bottom of the grave. The finds are placed in a wider context and methodological implications of the two identification methods applied to the chaff concentration are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Akeret Ö (2016) Botanische Reste aus dem Sarkophag eines Kindes aus dem temple de Daillens (VD) (Daillens – temple INT 11283). Rapport Integrative Prähistorische und Naturwissenschaftliche Archäologie, Basel University

Albert RM, Shahack-Gross R, Cabanes D et al (2008) Phytolith-rich layers from the late bronze and iron ages at Tel Dor (Israel): mode of formation and archaeological significance. J Archaeol Sci 35:57–75

Artelius T (1999) Arrhenaterum elatius ssp. bulbosum: Om växtsymbolik i vikingatida begravningar. In: Gustafsson A, Karlsson H (eds) Glyfer och arkeologiska rum— En vänbok till Jarl Nordbladh. Gotarc Series A 3. Göteborg University, Göteborg, pp 215–228

Bagge MS (2020) The extraordinary chamber grave from Fregerslev, Denmark. The find, excavation and future. In: Pedersen A, Sindbæk S (eds) Viking encounters. In: Proceedings of the 18th Viking Congress, Denmark, August 6–12, 2017. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, pp 505–516

Bagge MS, Hertz E (2021) The equestrian chamber grave, Fregerslev II. Initial results from an elite viking-age burial in East Jutland, Denmark. In: Pedersen A, Bagge MS (eds) Horse and rider in the late viking age. Equestrian burial in perspective. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, pp 14–33

Ball TB, Gardner JS, Anderson N (1999) Identifying inflorescence phytoliths from selected species of wheat (Triticum monococcum, T. dicoccon, T. dicoccoides, and T. aestivum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare and H. spontaneum) (Gramineae). Am J Bot 86:1,615-1,623

Ball TB, Davis AL, Evett RR, Ladwig JL, Tromp M, Out WA, Portillo M (2016) Morphometric analysis of phytoliths: recommendations towards standardization from the international committee for phytolith morphometrics. J Archaeol Sci 68:106–111

Ball T, Vrydaghs L, Mercer T, Pearce M, Snyder S, Lisztes-Szabó Z, Pető A (2017) A morphometric study of variance in articulated dendritic phytolith wave lobes within selected species of Triticeae and Aveneae. Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:85–97

Banerjea RY, Badura M, Brown A et al (2020) Feeding the crusades: Archaeobotany, animal husbandry and livestock alimentation on the Baltic frontier. Environ Archaeol 25:135–150

Behre K-E (1983) Ernährung und Umwelt der wikingerzeitlichen Siedlung Haithabu. Wachholtz, Neumünster

Bouby L, Marinval P (2004) Fruits and seeds from Roman cremations in Limagne (Massif Central) and the spatial variability of plant offerings in France. J Archaeol Sci 31:77–86

Bretz F, Hothorn T, Westfall P (2011) Multiple comparisons using R. Chapman & Hall, London

Brøndegaard VJ (1978) Folk og Flora. Dansk etnobotanik, vol 1. Rosenkilde og Bagger, Copenhagen

Brøndsted J (1936) Danish inhumation graves of the viking age. Acta Archaeol 7:81–228

Cabanes D, Albert RM(2011) Microarchaeology of a collective burial: Cova des Pas (Minorca).J Archaeol Sci38:1,119-1,126

Cederlund CO (1993) The Årby boat. Statens Historiske Museum, Stockholm

Cooremans B (2008) The Roman cemeteries of Tienen and Tongeren: Results from the archaeobotanical analysis of the cremation graves. Veget Hist Archaeobot 17:3–13

Cuddeford D (1995) Oats for animal feed. In: Welch RW (ed) The oat crop. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 321–368

Deforce K, van Hove M-L, Willems D (2015) Analysis of pollen and parasite eggs from medieval graves from Nivelles, Belgium: taphonomy of the burial ritual. J Archaeol Sci: Rep 4:596–604

Dejmal M, Lenka L, Fišáková Nývltová M et al (2014) Medieval horse stable. The results of multi proxy interdisciplinary research. PLoS ONE 9:e89273

Drenth E, Meurkens L, van Gijn AL et al (2011) Laat-neolitische graven. In: Lohof E, Hamburg T, Flamman J et al (eds) Steentijd opgespoord: Archeologisch onderzoek in het tracé van de Hanzelijn-Oude Land. Archol Rapport 38/ADC Rapport 2576. Archol, Leiden, pp 209–279

Eisenschmidt S (1994) Kammergräber der Wikingerzeit in Altdänemark. Universitätsforschungen zur prähistorischen Archäologie aus dem Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte der Universität Kiel 25. Habelt, Bonn

Eisenschmidt S (2004) Grabfunde des 8. bis 11. Jahrhunderts zwischen Kongeå und Eider. Zur Bestattungssitte der Wikingerzeit im südlichen Altdänemark. Studien zur Siedlungsgeschichte und Archäologie der Ostseegebiete 5. Wachholtz, Neumünster

Fahmy AG, Khodary S, Fadl M, El-Garf I (2008) Plant macroremains from an elite cemetery at predynastic hierakonpolis, upper Egypt. Int J Bot 4:205–212

Fennö Muyingo H (2000) Borgvallen II. Utvidgad undersökning av Borgvallen och underliggande grav 1997. Arkælogisk Forskningslaboratoriet Stockholms Universitet, Stockholm

Fredskild B (1977) Blommestenene fra Langeland. Urt 1977:25–26

Hamdy R, Fahmy AG (2018) Study of plant remains from the embalming cache KV63 at Luxor, Egypt. In: Mercuri AM, D’Andrea AC, Fornaciari R, Höhn A (eds) Plants and people in the African past. Springer, Cham, pp 40–56

Hansson A-M (1996) Bread in Birka and on Björkö. Laborativ Arkeologi 9:61–78

Hansson A-M (2002) Pre- and protohistoric bread in Sweden: a definition and a review. Civilisations 49:183–190

Hansson A-M, Bergström L (2002) Archaeobotany in prehistoric graves – concepts and methods. J Nordic Archaeol Sci 13:43–58

Helbæk H (1977) The Fyrkat grain: A geographical and chronological study of rye. In: Olsen O, Schmidt H (eds) Fyrkat. En jysk vikingeborg, Vol 1: Borgen og bebyggelsen. Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab, Copenhagen, pp 1–41

Hjelmqvist H (1982) Arkeologisk botanik—Något om metoder og mål. Sven Bot Tidskr 76:229–240

Hristova I (2015) The use of plants in ritual context during Antiquity in Bulgaria: Overview of the archaeobotanical evidence. Bulg e-J Archaeol 5:117–135

Holmboe J (1927) Nytteplanter og ugræs i Osebergfundet. In: Brøgger AW, Falk H, Schetelig H (eds) Osebergfundet 5. Den Norske Stat. Universitets Oldsaksamling, Oslo, pp 3–78

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50:346–363

IBM Corp (2015) IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 23.0. IBM Corp, Armonk

International Committee for Phytolith Taxonomy (ICPT) (2019) International Code for Phytolith Nomenclature (ICPN) 2.0. Ann Bot 124:189–199

Jaronsińska M, Nowak S, Noryśkiewicz AM, Badura M (2019) Plant identification and significance in funeral traditions exemplified by pillow filling from a child crypt burial in Byszewo (18th/19th centuries). Analecta Archaeologica Ressoviensia 14:187–197

Jones LHP, Milne AA, Wadham SM (1963) Studies of silica in the oat plant. 2. Distribution of the silica in the plant. Plant Soil 18:358–371

Juhola T, Henry AG, Kirkinen T, Laakkonen J, Väliranta M (2019) Phytoliths, parasites, fibers, and feathers from dental calculus and sediment from Iron Age Luistari cemetery, Finland. Quat Sci Rev 222:105888

Kalkman C (2003) Planten voor dagelijks gebruik. Botanische achtergronden en toepassingen. KNNV Uitgeverij, Utrecht

Karg S (2001) Blomster til de døde. Urter og blomster fra 14 renæssance-, barok og rokokobegravelser i Helsingør Domkirke. In: Hvass L, Bill-Jessen T, Madsen LB, Jensen PR, Aagaard K (eds) Skt. Olai Kirke: Restaureringen af Helsingør Domkirke 2000–2001 og undersøgelserne af de borgerlige begravelser. Helsingør Kommunes Museer, Helsingør, pp 133–142

Karg S (2007) Long term dietary traditions: Archaeobotanical records from Denmark dated to the Middle Ages and early modern times. In: Karg S (ed) Medieval food traditions in Northern Europe. National Museum, Copenhagen, pp 137–153

Körber-Grohne U (1985) Die biologischen Reste aus dem hallstattzeitlichen Fürstengrab von Hochdorf, Gemeinde Eberdingen (Kreis Ludwigsburg). In: Körber-Grohne U, Küster H (eds) Hochdorf 1. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 19. Theiss, Stuttgart, pp 87–265. In

Kroll HJ (1975) Ur- und frühgeschichtlicher Ackerbau in Archsum auf Sylt. Eine botanische Großrestanalyse. Dissertation, Christians-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel

Kühn M (2010) Ergebnisse der archäobotanischen Untersuchung. In: Müller K (ed) Gräben, Graben, Generationen: Der frühmittelalterliche Friedhof (7. Jahrhundert) von der Früebergstrasse in Baar (Kanton Zug). Antiqua 48. Archäologie Schweiz, Basel, pp 39–44

Langdon J (1982) The economics of horses and oxen in medieval England. Agric Hist Rev 30:31–40

Lavrsen J (1960) Brandstrup. En ryttergrav fra det 10. århundrede. Kuml 10:90–105

Lempiäinen-Avci M, Laakso V, Alenius T (2017) Archaeobotanical remains from inhumation graves in Finland, with special emphasis on a 16th century grave at Kappelinmäki, Lappeenranta. J Archaeol Sci: Rep 13:132–141

Lodwick L (2014) Identifying ritual deposition of plant remans: A case study of stone pine cones in Roman Britain. In: Brindle T, Allen M, Durham E, Smith A (eds) TRAC 2014: Proceedings of the twenty-fourth annual theoretical Roman Archaeology conference. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 54–69

Lu H, Zhang J, Wu N, Liu K-b, Xu D, Li Q (2009) Phytoliths analysis for the discrimination of foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and common millet (Panicum miliaceum). PLoS ONE 4:e4448

Malmros C (2009) Træet til ligkister, våben og redskaber. Identifikation af træ og læder fra ryttergraven i Grimstrup og andre vikingegrave. In: Stoumann I (ed) Ryttergraven fra Grimstrup og andre vikingetidsgrave ved Esbjerg. Arkæologiske Rapporter fra Esbjerg Museum 5:290–322

Matterne V, Derreumaux M (2008) A Franco-Italian investigation of funerary rituals in the Roman world, “les rites et la mort à Pompéi”, the plant part: a preliminary report. Veget Hist Archaeobot 17:105–112

McCullagh P, Nelder JA (1989) Generalized Linear models, 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall, London

Mégaloudi F, Papadopoulos S, Sgourou M (2007) Plant offerings from the classical necropolis of Limenas, Thasos, northern Greece. Antiquity 81:933–943

Moore-Colyer RJ (1995) Oats and oat production in history and pre-history. In: Welch RW (ed) The oat crop: production and utilization. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 1–33

Müller-Wille M (1987) Das wikingerzeitliche Gräberfeld von Thumby-Bienebek (Kr. Rendsburg-Eckernförde) Teil 2. Offa-Bücher 62. Wachholtz, Neumünster

Murphy P (1986) Botanical evidence. In: Lawson AJ (ed) Barrow excavations in Norfolk 1950–1982. East Anglian Archaeology Report 29. Norfolk Archaeology, Norfolk, pp 43–45

Noble G, Brophy K (2011) Ritual and remembrance at a prehistoric ceremonial complex in central Scotland: Excavations at Forteviot, Perth and Kinross. Antiquity 85:787–804

Olivier L (1999) The Hochdorf ‘princely’ grave and the question of the nature of archaeological funerary assemblages. In: Murray T (ed) Time and archaeology. Routledge, London, pp 109–138

Out WA (2020) Development of identification criteria of non-dietary cereal crop products by phytolith analysis to study prehistoric agricultural societies. In: Müller J, Ricci A (eds) Past societies. Human development in landscapes. Sidestone Press, Leiden, pp 37–50

Out WA, Madella M (2016) Morphometric distinction between bilobate phytoliths from Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica leaves. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 8:505–521

Out WA, Pertusa Grau JF, Madella M (2014) A new method for morphometric analysis of opal phytoliths from plants. Microsc Microanal 20:1,876-1,887

Out WA, Enevold R, Mikkelsen PH, Jensen PM, Portillo M, Schwartz M (2021) Wood, seeds and fruits, phytoliths, pollen and non-pollen palynomorphs of the horse burial of Fregerslev II. In: Pedersen A, Bagge MS (eds) Horse and rider in the Late Viking Age: Equestrian burial in perspective. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, pp 61–81

Out WA, Ryan P, García-Granero JJ, Barastegui J, Maritan L, Madella M, Usai D (2016) Plant exploitation in neolithic Sudan: A review in the light of new data from the cemeteries R12 and Ghaba. Quat Int 412(B):36–53

Palmer C, van der Veen M (2002) Archaeobotany and the social context of food. Acta Palaeobot 42:195–202

Pedersen A (1974) Gramineernes udbredelse i Danmark. Spontane og naturaliserede arter. Bot Tidsskr 68:177–343

Pedersen A (2014) Dead warriors in living memory. A study of weapon and equestrian burials in Viking-Age Denmark, AD 800–1000. Publications from the National Museum Studies in Archaeology & History 20. University Press of Southern Denmark, Odense

Pedersen A (2021) Equestrian burial in viking-age Denmark. In: Pedersen A, Bagge MS (eds) Horse and rider in the late viking age. Equestrian burial in perspective. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, pp 129–139

Pedersen A, Bagge MS (eds) (2021) Horse and rider in the late Viking Age. Equestrian burial in perspective. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus

Pinder D, Shimada I, Gregory D (1979) The nearest-neighbor statistic: archaeological application and new developments. Am Antiq 44:430–445

Pinheiro JC, Bates DM (2000) Mixed-effects models in S and S-PLUS. Springer, New York

Portillo M, Albert RM (2011) Husbandry practices and livestock dung at the Numidian site of Althiburos (el Médéina, Kef Governorate, northern Tunisia): the phytolith and spherulite evidence. J Archaeol Sci 38:3,224-3,233

Portillo M, Ball T, Manwaring J (2006) Morphometric analysis of inflorescence phytoliths produced by Avena sativa L. and Avena strigosa Schreb. Econ Bot 60:121–129

Portillo M, Rosen AM, Weinstein-Evron M (2010) Natufian plant uses at el-Wad terrace (Mount Carmel, Israel): the phytolith evidence. Eurasian Prehist 7:99–112

Portillo M, Ball TB, Wallace M et al (2020) Advances in morphometrics in archaeobotany. Environ Archaeol 25:246–256

Portillo M, Kadowaki S, Nishiaki Y, Albert RM (2014) Early Neolithic household behavior at Tell Seker al-Aheimar (Upper Khabur, Syria): A comparison to ethnoarchaeological study of phytoliths and dung spherulites. J Archaeol Sci 42:107–118

Portillo M, Llergo Y, Ferrer A, Albert RM (2017) Tracing microfossil residues of cereal processing in the archaeobotanical record: an experimental approach. Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:59–74

Power RC, Rosen AM, Nadel D (2014) The economic and ritual utilization of plants at the Raqefet cave Natufian site: the evidence from phytoliths. J Anthropol Archaeol 33:49–65

Preiss S, Matterne V, Latron F (2005) An approach to funerary rituals in the Roman provinces: plant remains from a Gallo-Roman cemetery at Faulquemont (Moselle, France). Veget Hist Archaeobot 14:362–372

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/. Last access 22 February 2021

Rapan Papeša A, Kenéz A, Petö Á (2015) The archaeobotanical assessment of grave samples from the Avar Age cemetery of Nuštar (Eastern Croatia). Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu 32:261–288

Reed K, Ghica V, Smuk A, Dugonjić A, Mihaljevic M, Filipović, Balen J (2022) Untangling the taphonomy of charred plant remains in ritual contexts: late antique and medieval churches and graves from Croatia. J Field Archaeol 47:164–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2021.2022274

Robinson D (1994) Plants and vikings: everyday life in viking age Denmark. Bot J Scotl 46:542–551

Rosen AM (1992) Preliminary identification of silica skeletons from Near Eastern archaeological sites: an anatomical approach. In: Mulholland R Jr. (ed) Phytolith systematics. Emerging issues. Plenum Press, New York, pp 129–147

Rösch M (2005) Pollen analysis of the contents of excavated vessels. Direct archaeobotanical evidence of beverages. Veget Hist Archeaobot 14:179–188

Ryan P (2018) Plants as grave goods: Microbotanical remains (phytoliths) from the ‘white deposits’ in the graves. In: Welsby DA (ed) A Kerma Ancien cemetery in the northern Dongola Reach. Excavations at site H29. Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publication 22. Archaeopresss, Oxford, pp 203–206

Šálková T, Dohnalová A, Novák J, Hiltscher T, Jiřík J, Vávra J (2016) Unrecognized taphonomy as a problem of identification and the scale of contamination of archaeobotanical assemblages—the example of Prague—Zličin Migration Period burial ground. Interdiscip Archaeol 7:87–110

Sangster AG, Hodson MJ, Tubb HJ (2001) Silicon deposition in higher plants. In: Datnoff LE, Snyder GH, Korndörfer GH (eds) Silicon in agriculture. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 85–113

Schaarschmidt F, Vaas L (2009) Analysis of trials with complex treatment structure using multiple contrast tests. HortScience 44:188–195

Sereno PC, Garcea EAA, Jousse H et al (2008) Lakeside cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 years of holocene population and environmental change. PLoS ONE 3:e2995

Shlishlina NI, Bobrov AA, Simakova AM, Troshina AA, Sevastyanov VS, van der Plicht J (2018) Plant food subsistence in the human diet of the bronze age Caspian and low don steppe pastoralists: archaeobotanical isotope and 14C data. Veget Hist Archaeobot 27:833–842

Skaarup J, Kromann A (1976) Stengade II: En langelandsk gravplads med grave fra romersk jernalder og vikingetid. Langelands Museum, Rudkøbing

Søe NE, Odgaard BV, Nielsen AB, Olsen J, Kristiansen SM (2017) Late Holocene landscape development around a roman iron age mass grave, Alken Enge, Denmark. Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:277–292

Sørensen AC (2001) Ladby. A Danish ship-grave from the Viking Age. Ships and boats of the North 3. Viking Ship Museum, Roskilde

Stoumann I (2009) Ryttergraven fra Grimstrup og andre vikingetidsgrave ved Esbjerg. Arkæologiske Rapporter fra Esbjerg Museum 5. Sydvestjyske Museer, Ribe

Sulas F, Orfanou V, Ljungberg T, Kristiansen SM (2021) Mapping the invisible traces. Soil micromorphology at Fregerslev II. In: Pedersen A, Bagge MS (eds) Horse and rider in the late viking age. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, pp 101–113

Sulas F, Bagge MS, Enevold R et al (2022) Revealing the invisible dead: Integrated bio-geoarchaeological profiling exposes human and animal remains in a seemingly ‘empty’ Viking-Age burial. J Archaeol Sci 141:105589

Tranberg A (2015) Burial customs in the Northern Ostrobothnian region (Finland) from the Late Medieval period to the 20th century. Plant remains in graves. In: Tarlow S (ed) The archaeology of death in Post-Medieval Europe. De Gruyter, Warszawa, pp 189–203

Vandorpe P (2019) Pflanzliche Beigaben in Brandbestattungen der Römischen Schweiz. Jb Archäologie Schweiz 102:57–76

Van Zeist W, Palfenier-Vegter R (1979) Agriculture in medieval Gasselte. Palaeohistoria 21:267–299

Vaz FC, Braga C, Tereso JP et al (2021) Food for the dead, fuel for the pyre: symbolism and function of plant remains in provincial Roma cremation rituals in the necropolis of Bracara Augusta (NW Iberia). Quat Int 593–594:372–383

Vermeeren C, van Haaster H (2002) The embalming of the ancestors of the Dutch royal family. Veget Hist Archaeobot 11:121–126

Weibull J, Bojesen LLJ, Rasomavicius V (2002) Avena strigosa in Denmark and Lithuania: prospects for in situ conservation. Plant Genet Resour Newsl 13l:1–6

Wendrich W, Ryan P (2012) Pytoliths and basketry materials at Çatalhöyük (Turkey): timelines of growth, harvest and objects life histories. Paléorient 38:55–63

Wilson DG (1979) Horse dung from Roman lancaster: a botanical report. In: Körber-Grohne U (ed) Festschrift Maria Hopf zum 65. Geburtstag am 14. September 1979. Archaeo-Physika 8. Habelt, Bonn, pp 331–350

Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E (2012) Domestication of plants in the Old World, 4th edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the A.P. Møllerske Støttefond (Grant No. 11372), the Augustinus Foundation (Grant No. 16-2213), the Agency for Culture and Palaces, and Skanderborg Municipality, who supported the excavation and analyses. The authors are also grateful to two anonymous reviewers and the editor K. Neumann for their helpful comments that substantially improved the paper, C. Saugbjerg and M. Schwartz for sample collection and A.K. Tjellden for additional information about the phytolith samples, T. Ljungberg for providing the control sample, the archaeological IT-team from Moesgaard Museum for practical support during the collection of the morphometric data, the Graphics Department of Moesgaard Museum for kind help with the illustrations, A. Philips of the University of Amsterdam for the preparation of the phytolith samples, A.M. Rosen for help with the phytolith identifications, S. Eisenschmidt, C. Hedenstierna-Jonson, J. Ljungkivst, M. Schepers, Ö. Akeret, H. Kroll, F. Verbruggen, J.-W. de Kort and members of the archaeobotany and zooarch email lists for literature suggestions, and C.F. Sørensen from the Museums of Easter Funen and P.S. Henriksen and P. Pentz from the National Museum in Denmark for information on the finds from the Ladby ship burial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by K. Neumann.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Out, W.A., Hasler, M., Portillo, M. et al. The potential of phytolith analysis to reveal grave goods: the case study of the Viking-age equestrian burial of Fregerslev II. Veget Hist Archaeobot (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-022-00881-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-022-00881-2