Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis causes progressive joint destruction in the long term, causing a deterioration of the foot and ankle. A clinical practice guideline has been created with the main objective of providing recommendations in the field of podiatry for the conservative management of rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, healthcare professionals involved in foot care of adults with rheumatoid arthritis will be able to follow practical recommendations. A clinical practice guideline was created including a group of experts (podiatrists, rheumatologists, nurses, an orthopaedic surgeon, a physiotherapist, an occupational therapist and patient with rheumatoid arthritis). Methodological experts using GRADE were tasked with systematically reviewing the available scientific evidence and developing the information which serves as a basis for the expert group to make recommendations. Key findings include the efficacy of chiropody in alleviating hyperkeratotic lesions and improving short-term pain and functionality. Notably, custom and standardized foot orthoses demonstrated significant benefits in reducing foot pain, enhancing physical function, and improving life quality. Therapeutic footwear was identified as crucial for pain reduction and mobility improvement, emphasizing the necessity for custom-made options tailored to individual patient needs. Surgical interventions were recommended for cases which were non-responsive to conservative treatments, aimed at preserving foot functionality and reducing pain. Moreover, self-care strategies and education were underscored as essential components for promoting patient independence and health maintenance. A series of recommendations have been created which will help professionals and patients to manage podiatric pathologies derived from rheumatoid arthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Foot involvement is very significant in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Approximately 20% of patients report foot symptoms when their disease is diagnosed. As the disease evolves, this percentage increases to 90% [1,2,3]. In the initial stages, foot symptoms may go unnoticed in clinical assessments, and it is important to use physical assessment and radiological methods in the foot region to detect them [1, 4, 5].

The foot suffers joint destruction, increased ligament laxity and muscle-tendon dysfunction, modifying its biomechanics [1, 5, 6]. Consequently, RA negatively affects the quality of life, pain, function and stability of patients with RA, increasing their disability and making it difficult to carry out the usual tasks that require standing, carrying weight or walking long distances [3, 5, 7, 8].

To date, there are no Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) that exclusively describe how pathologies affecting the foot and ankle should be addressed [9, 10]. The variability of clinical practice could lead to incorrect implementation of standardized protocols and misinterpretation of recommendations. This detrimentally affects patients through clinical errors, inadequate follow-up procedures, and treatment inaccuracies [11].

A CPG is a set of recommendations based on a systematic review of the evidence and the assessment of the risks and benefits of different alternatives, aiming to optimise the healthcare for patients. GPCs correspond to the first level of scientific evidence, with the function of helping professionals to make decisions, summarizing the evidence and transmitting confidence by being powerful instruments to reduce clinical variability [12].

Conservative intervention in the rheumatic foot should be part of the comprehensive evaluation of these patients, as well as to consult all the steps of the process in a CPG. The objective of this paper is to evaluate the efficacy of various interventions for managing foot and ankle issues in patients with RA, and to develop evidence-based recommendations that enhance patient care. Through a systematic literature review and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) analysis, this study aims to identify the most effective treatments for alleviating pain, improving functionality, and enhancing the quality of life for these patients, while also emphasizing the importance of tailored, patient-specific approaches in clinical practice.

Methods

Creation of the guide development group (GDG)

A multidisciplinary team was selected with the intent to get all relevant groups experienced with RA. The group was made up of experts in GPC methodology, health professionals and patients from different geographical areas (Malaga, Alicante, Tenerife, Granada and Sevilla, increasing the CPG value, dissemination and implementation. This is reflected by: five podiatrists, two rheumatologists, three nurses, one orthopaedic surgeon, one physiotherapist, one occupational therapist and four patients with RA. The multidisciplinary team was selected for its extensive experience in the management of RA and for its research career focused on RA.

The composition of the GDG is described below:

-

Coordination: a specialist in foot rheumatology, as principal investigator (PI) and a specialist in CPG methodology coordinated the clinical and methodological aspects of the CPG.

-

Group of experts: chosen for their qualities, experience and knowledge of RA. They were responsible for the development of the CPG recommendations.

-

Peer reviewers: Methodological experts were tasked with systematically reviewing the available scientific evidence and developing the information that serves as a basis for the expert group to make recommendations.

-

Patients: Two patients participated in the processing group and two patients participated as external reviews. All of them were patients from the Regional University Hospital of Malaga, Spain.

To ensure the optimal progress of the project, a detailed schedule was devised. None of the members of the group had conflicts of interest.

Formulation of clinical questions

Initially, the scope and objectives of the guideline were collaboratively defined and unanimously agreed upon by all members of the GDC, including experts, patients, and through reference to scientific literature. The formulation of clinical questions followed a consensual approach, ensuring a structured format aligned with the Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework [13]. This not only enhances the scientific rigor but also facilitates the formulation of recommendations. Patient involvement remained integral throughout the entirety of the process. Subsequently, upon reaching consensus on the proposed objectives, clinical questions were established to address these objectives, as outlined in Table 1. Preferably, we sought to answer these questions through systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Finally, the PICO questions that were answered were:

-

What is the role of the implementation of foot care in improving health, the ability to move autonomously, independence and functionality, and improving quality of life in patients with RA compared to not implementing foot care?

-

What is the most commonly used foot care in RA patients with foot and ankle involvement?

-

What indicators suggest progression of foot and ankle involvement in RA disease? How to improve foot and ankle symptoms in RA?

-

How to implement foot care in patients with RA?

-

How to reduce variability in foot care in patients with RA?

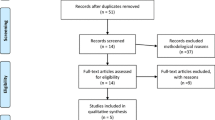

Literature search, evaluation and synthesis of evidence

A systematic review of the scientific literature was carried out and in cases where there was no scientific literature, a Delphi survey was carried out [12].

The search was carried out in the databases of Medline (through Pubmed), SCOPUS, CINHAL, PEDro using the following terms: rheumatoid arthritis, callus, corn, hyperqueratosis, nails, foot, forefoot, feet, ankle, ankle joint, joint, footwear, shoe*, boot*, deck, trainer*, sneaker, orthoses, orthosis, insole, plantar, bones of lower extremity, Hallux, first metatarsophalang*, surgic*, non-conservative treatment, pain, disab*, funct*, foot lesions, ulcer, skin lesions, glucocorticoids, triamcinolone, hyaluronic acid, viscosupplements, platelet-rich plasma, injections, intra-articular. Free language terms and descriptors were combined to balance the sensitivity and specificity of the searches (Annex 8). No time restrictions were set. The search ended in June 2022, and was limited to human studies, written in either Spanish or English.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they presented the following characteristics.

-

Population: Adult patients (over 18) diagnosed with RA and/or diagnosed according to the 2010 RA criteria approved by the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism [14].

-

Intervention: conservative and non-conservative foot care.

-

Outcome variables:

-

Primary Outcome - Improvement in Foot Health: Reduction in foot pain as measured by the Foot Function Index (FFI) or Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores.

-

Secondary Outcomes: Improved Health: Lower overall RA disease activity scores, such as the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), indicating better systemic health. Autonomous Movement: Increased ability to perform daily activities without assistance, measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI). Independence: Enhanced self-sufficiency in personal care and mobility tasks, potentially assessed through patient-reported outcome measures. Functionality: Improved physical function, specifically in the lower extremities, measured by the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS). Quality of Life: Higher scores on the Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life (RAQoL) questionnaire or the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Symptoms: Reduction in specific RA symptoms such as joint swelling, stiffness duration in the morning, and the number of tender/swollen joints. Adherence to Treatments: Higher rates of compliance with prescribed medication and non-pharmacological interventions, monitored through patient self-reports or pharmacy refill rates. Reduced Variability: Decreased diversity in treatment approaches among healthcare providers, indicating standardization of care practices, assessable through review of medical records or surveys.

-

Study design: systematic reviews or meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials, observational studies and case-control studies.

Studies which included people under 18 years of age or pregnant women, conference abstracts, posters, narrative reviews, letters, and any type of unpublished study were excluded.

Assessment of the quality of the studies

Two members of the GDG assessed the risk of bias of the individual studies. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was used [15] to evaluate randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) [16] for observational studies. NOS is a valid tool for assessing the quality of any observational design that has an adapted version [17, 18], which assesses selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, and reporting bias.

Each RCT was assessed to consider if there was any bias related to the following domains: the randomisation process; deviations from interventions; lack of outcome data; outcome measurement and selection of reported outcome. In addition, the Preferred Reported Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) was used to evaluate the systematic reviews and meta-analyses [19].

Formulation of recommendations

In formulating recommendations, careful consideration was given to the quality, quantity, and consistency of scientific evidence, as well as their applicability and clinical implications. Any contentious or unsupported recommendations were addressed through consensus during a dedicated meeting of the GDG.

In order to empower patients and their families in making informed decisions regarding their healthcare, specific educational materials have been incorporated. These materials, available in Annex 9, are designed to provide comprehensive information tailored to the needs and understanding of patients and their families. By offering accessible resources, the aim is to enhance communication between healthcare providers and patients, fostering a collaborative approach to treatment and care.

GPC external review

An external review of the guideline was carried out by professionals selected for their knowledge of RA and methodology used to create guidelines. The ultimate goal was to increase the external validity of the document and ensure the accuracy of its recommendations.

In addition, OpenReuma contributed to the process of public exposure and dissemination. The present guide was available on the OpenReuma website along with a form for collecting statements. OpenReuma is a non-profit scientific association that brings together healthcare professionals with an interest in rheumatology.

Evaluation and synthesis of the evidence

The quality of evidence was evaluated utilizing the rigorous methodology established by the GRADE group. Recommendations underwent a voting process, scored on a scale of 0 to 10, with those averaging ≥ 6 among the GDG advancing to the next stage of the CPG. Recommendations scoring below 6 points underwent thorough deliberation to determine their inclusion or exclusion from further consideration [20].

Through the Guidelines Development Tool (http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/), confidence was assessed to support the recommendations developed. As a result, each recommendation received a rating: high, moderate, low, and very low [21, 22].

Results

For a better understanding and dissemination of the recommendations, the answers have been divided into the different treatments: chiropody, footwear, foot orthoses, surgery, self-care, ulcer management, physical therapy, and injections.

All recommendations, except physical therapy, were developed following the results from a systematic literature review and a subsequent analysis using the GRADE system for drafting the recommendations. In instances where scientific literature was unavailable, a Delphi survey was conducted among the members of the GDC to gather expert consensus.

Our findings reveal varied levels of evidence across different treatment modalities for foot and ankle management in patients with RA. This section delineates the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations derived from the analysis.

-

1.

Chiropody: The GRADE analysis indicates a very low level of evidence regarding the efficacy and outcomes of chiropody interventions (Annex 1).

-

2.

Footwear: The assessment of therapeutic footwear, including both custom and standard options, yielded a moderate to very low grade of evidence (Annex 2).

-

3.

Foot Orthoses: The evidence supporting the use of foot orthoses was rated as moderate (Annex 3).

-

4.

Surgery: Surgical interventions for foot and ankle issues in rheumatoid arthritis patients were found to have a very low grade of evidence (Annex 4).

-

5.

Self-Care: The effectiveness of self-care strategies, including education on foot health and routine care practices, was assessed to have a very low level of evidence (Annex 5).

-

6.

Ulcer Management: Similarly, the GRADE assessment for ulcer management strategies yielded a very low level of evidence (Annex 6).

-

7.

Injections for Joint and Tendon: The evaluation of the efficacy of injections, specifically in joints and tendons in the foot and ankle, also received a very low evidence grade (Annex 7).

The recommendations are as follows:

Chiropody recommendations

Are chiropodies recommended for patients with RA? Do chiropodies need to be complemented with other treatments?

Hyperkeratotic lesions on the feet cause pain and disability to patients despite being considered a minor problem [23]. 65% of patients with connective tissue diseases present plantar callosities, and this percentage increases in patients with RA due to the alterations produced by the disease itself [24, 25]. When these hyperkeratoses are left untreated, they may cause some deeper damage to the tissues, which could lead to tissue ulceration [24].

Toe deformities, presence of hallux valgus and flat feet are risk factors associated with the appearance of hyperkeratosis, which can cause pain [24,25,26]. These risks factors are frequently present in patients with RA. These patients have pressure peaks which are higher than normal values, with an atypical distribution of pressures and forces acting on the foot [27].

Chiropody is known as the mechanical debridement of thickened skin with a scalpel blade, being the most common treatment for painful hyperkeratotic lesions [28]. Debridement decreases focal pressures, reducing the appearance of ulcers and significantly facilitating their healing [29]. In addition, in the short term, there is a pain decrease and an improvement in functionality after treatment, which is related to an increase in gait speed, cadence, stride length and bipodal support time in patients with RA [29].

However, it should be noted that isolated debridement of painful hyperkeratoses in the forefoot should not be used, even if it reduces pain in the short term [29]. This technique should be combined with the use of appropriate footwear and foot orthoses in patients with RA [28, 29].

Therefore, it should be concluded that chiropodies are recommended for the removal of hyperkeratotics, thus achieving a reduction in pain in the short term and an improvement in functionality. In addition, they should be complemented by orthopedic treatments, including appropriate footwear and foot orthoses (Table 2).

Footwear recommendations

What are the benefits of therapeutic footwear for patients with RA?

The choice of footwear might be an issue for RA patients. Therapeutic footwear includes custom-made and off-the-shelf footwear. Custom-made therapeutic footwear is made for an individual patient based on individual measurements and specifications, so a variety of technical adaptations can be incorporated; while ready-made therapeutic footwear includes mass-produced shoes with greater depth, support, or technical adaptations [30]. When patients with RA wear therapeutic footwear, an improvement in pain and mobility has been demonstrated as these patients present complex needs due to their pain and structural changes to their feet. Due to the deformity of the patients, standard footwear can cause pressure areas due to poor fit, whereas orthopedic footwear is designed to allow space for these deformities, reducing pressure, which can lead to pain, skin lesions, and ulcers. However, patients with RA, particularly women, often find therapeutic footwear unacceptable due to aesthetics, price, or limited availability. This situation often leads to dissatisfaction when choosing and wearing footwear. Their social behaviour might be altered, causing a negative impact on body image and emotions due to their footwear [31, 32].

Patients who decide to wear standardized footwear can do so by looking for a more aesthetic alternative to therapeutic footwear. However, standardized or ready-made footwear may not be suitable and can exacerbate their foot problems, creating an issue when wearing foot orthoses [32, 33].

Randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses indicate that therapeutic footwear benefits RA patients in terms of pain reduction and improvement in physical function, compared standard footwear. In addition, standardized therapeutic footwear provides benefits in foot functionality, foot pain, physical functionality, walking speed, stride length, and quality of life [34, 35] (Table 2).

Foot orthoses recommendations

What are the effects of foot orthoses for patients with RA?

Foot orthoses are an important conservative treatment option for RA-related foot problems and are frequently prescribed in clinical practice [36]. They are placed inside the shoe to control the movement of the foot when walking to limit pain and deformity of the foot, modifying the neuromuscular and skeletal system [36, 37]. Its main objectives for patients with RA is to reduce pain and disability, improving the patient’s quality of life [38].

The efficacy of foot orthoses in patients with RA has been confirmed, including both personalized orthoses, which are specifically tailored to patients, and standardized orthoses [39, 40]. Its efficacy may be influenced by shorter duration of illness, younger age, and pain and disability values [41].

Early and ongoing interventions with foot orthoses provide a significant reduction in foot pain in the short term, with a reduction in disability and improved long-term foot health outcomes. Early intervention has demonstrated a pain reduction within the first 3 months of use and with a small additional symptomatic improvement up to 6 months [42]. It has been suggested that this early management helps avoid or delay late-stage orthopaedic surgery [43]. With these interventions, a window of opportunity is generated in early stage RA with the aim of minimizing foot deformation before irreversible joint damage occurs [41, 43,44,45].

Foot orthoses vary widely in their material, design, and manufacturing method. This variation is further increased by additional elements such as posts, wedges, and cushioning [46]. It has been concluded that foot orthoses made from soft materials can reduce plantar pressure of the forefoot compared to semi-rigid materials [47], while other studies concluded that rigid and semi-rigid materials in custom foot orthoses reduce rearfoot pain among patients with RA [48]. Therefore, more high-quality, better-designed studies with more specific parameters are needed (Table 2).

Surgical recommendations

Which foot surgeries are recommended for patients with RA?

Osteoarticular surgical treatment of the foot should allow the reduction of deformity, pain and preservation of functionality in patients with RA. The indication for surgery is mainly due to pain, which has not improved with conservative treatment and reduces the patient’s quality of life. The intention of surgery is not curative, since the degenerative evolution of the disease will continue to progressively deteriorate the rest of the joints.

The surgical technique will depend on the deformity, age and bone quality, as well as the degree of joint destruction [49]. The surgical techniques most commonly described in the literature are arthroplasty, arthrodesis and osteotomy of the metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP) and total ankle arthroplasty [50].

Short-term studies (6–12 months) report an improvement of foot pain [51], but long-term studies report increased pain and recurrence of deformities [52]. In most studies, the follow-up period is insufficient despite satisfactory results.

Surgeries of the MTP joints and toes have been reported most frequently [52, 53], coinciding with the prevalence of foot deformities in RA, having a high frequency of hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, and claw toes [54, 55].

First MTP joint arthrodesis [51, 56, 57] and second to fifth MTP joint arthroplasty [58], are the most documented surgeries [26].

Post-surgical iatrogenic effects have also been described, such as: ankylosis in the midfoot [59], increase in rearfoot varus, and increased forefoot stiffness, failed total ankle arthroplasty leading to arthrodesis of the ankle [60]. However, in a recent meta-analysis, it has been concluded that total ankle replacement is a safe procedure for RA patients with difficulties close to other reasons for ankle replacement [61] (Table 2).

Self-care recommendations

Is self-care recommended for patients with RA?

Self-care is the strategy that should be carried out to cope with life events and stressors that can have a negative impact on health, with the aim of alleviating the symptoms of the disease, promoting good health, achieving the independence of the patient [62].

Self-care, therefore, is a regulatory function that patients acquire through health education carried out by health professionals which may be influenced by different factors: social support, demographic characteristics, knowledge of the disease, and physical function [63].

It should be taken into consideration that the patient’s ability to carry out self-care can vary dependant on: age, illness, health education, health status, physical condition, and perceived pain [64].

Patients with RA may have difficulties in carrying out their self-care due to the disability caused the evolution of the disease, therefore, self-care of the feet must be encouraged from the beginning of the disease, being incorporated into the patient’s usual tasks. Foot care is important to prevent and maintain their health, promoting independence, mobility and personal and social activity. It is essential that the patient is able to identify problems in their feet, as well as having the knowledge and skills to treat them [65].

Therefore, it has been concluded that daily hygiene, skin and nail care, the use of appropriate footwear and socks, the use of toe spacers if necessary, the use of foot orthoses and specific exercises for the lower limb are included as self-care of the feet [66] (Table 2).

Ulcer management recommendations

Is it recommended the care of skin ulcers in patients with RA?

The management of foot problems in patients with RA may involve a variety of interventions, such as treatment of skin lesions resulting from ulcers [67]. Previous studies established that ulceration has been more commonly observed in female RA patients with prolonged disease, with many patients presenting multiple episodes of ulceration and not always in the same site [68].

As time passes and the disease progresses, foot deformity and trauma caused by footwear can increase the risks of damage to the surrounding skin, resulting in loss of skin integrity and can lead to foot ulcers [69]. The overall prevalence of foot ulceration in patients with RA is between 10 and 13% [69, 70], with an added impact on their quality of life [70, 71].

Regarding the location of ulcers, more than 50% are located at the toes, and 15% at the rearfoot, the most common place being on the dorsal aspect of hammertoes [68], followed by the plantar side of the metatarsal heads [70, 71]. Increased age and duration of the disease increases the risk of ulcers [69]. In addition, patients who have undergone treatment with targeted therapies are at increased risk of infection, causing skin fragility and hindering tissue repair [69, 70] (Table 2).

Physical therapy recommendations

Which type of physical exercise is recommended for patients with RA?

Non-pharmacological treatment modalities are often used together with pharmacological treatment in patients with RA [72]. There are different modalities of physical therapy, including physical exercise, which are used in RA to generate therapeutic physiological effects with the aim of reducing pain or restoring function [73].

Physical exercise can be considered as part of physical therapy. It is necessary to practice exercise supervised by a professional if the patient presents with any limitations in activities of daily living or if the patient is unable to achieve an adequate level of physical functioning independently. Therefore, it is recommended to perform moderate physical exercise with limited supervision as long as the intensity is respected and frequency and duration is adequate for each patient [74,75,76].

Although there are currently no specific recommendations for foot physical exercises for individuals with foot and ankle osteoarthritis (OA) [77], exercise remains a promising intervention for improving outcomes related to RA and alleviating negative emotional states [78].

Effective exercise interventions induce physiological responses such as increased flexibility, muscular strength, and cardiovascular fitness. This efficacy is contingent on the appropriate intervention, correct dosing, and patient adherence [79]. Cardiovascular training for individuals with RA should involve no-impact sports such as Nordic walking, dancing, cycling, or water-based exercises [78]. The recommended intensity ranges from moderate to vigorous, with high-intensity training—up to 90% of the predicted maximal heart rate or 80% of one-repetition maximum—proving effective and feasible for people with RA [80].

In studies on foot and ankle OA, muscle strength, kinetics, and kinematics are objective measures of function often specified as secondary outcomes [81,82,83,84]. Therefore, exercises focusing on foot stretching, strengthening, proprioception, and flexibility may be beneficial for patients with foot and ankle OA. However, there is limited evidence on the effects of flexibility exercises, and almost no literature evaluates neuromotor exercises [78].

According to Shamus J et al. [81], incorporating sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis longus strengthening and gait training to a physical therapy program for first MTP joint OA, can significantly reduce pain intensity. Additionally, foot and ankle exercises could be an effective treatment not only for improve local pain on foot and ankle, but also could be a strategy for improving pain and functional deficits in individuals with patellofemoral pain [85].

In a meta-analysis is has been confirmed that strength exercises reported a positive effect on pain in the short and medium term, but it did not increase the aerobic capacity of the patients. On the other hand, they concluded that aerobic exercise improved the capacity of the patient to practice physical activity, but it did not report a positive nor negative effect in pain. Therefore, the most important thing is to consider the evolution of the patient and their symptoms, creating personalized exercise program [86].

Electrotherapy is used to control pain and increase muscle strength and function. One form of electrotherapy that is often used is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), which can help relieve pain [87].

Thermotherapy consists of the local application of cold or heat in isolation or through contrast baths with immersion in hot and cold water [88]. However, the effects of contrast baths may be more beneficial than applying cold during acute phases of pain [88]. Dry or water-jetted local heat can be used to provide short-term pain relief and to decrease joint stiffness, while paraffin wax baths provide longer-term results according to the British Society of Rheumatology (BSR) and the British Health Professionals in Rheumatology (BHPR) [72]. However, paraffin baths should be avoided in patients presenting with an active RA flare-up [73].

The warming effects of continuous ultrasound can also reduce muscle spasms and stimulate blood flow to help decrease inflammatory toxins [89].

Low-level laser therapy is another modality for relieving pain and improving function in patients with RA. The laser emits a single wavelength of pure light, which causes a photochemical reaction within the cells and can have an effect on flexibility and pain [90] (Table 2).

Injection recommendations

Which are the effects of corticosteroid injection for patients with RA?

Intra-articular corticosteroid injections are frequently used in the treatment of RA throughout the lower limb, although with the greatest evidence of efficacy confined to the knee joint. Meta-analyses have shown a positive short-term therapeutic effect, which may be mistaken for a placebo effect. Corticosteroid injections are capable of improving pain, and to a lesser extent, stiffness and physical function. This has been concluded after the analysis of clinical and radiographic data [91]. In addition, these injections are effective in the treatment of tenosynovitis, especially if combined with foot orthoses, improving pain levels and functionality of the foot [92].

Corticosteroid injection, specifically triamcinolone hexacetonide, is effective at reducing pain and inflammation [93]. In pharmacokinetic studies, corticosteroids with more microcrystalline properties have a longer half-life at the joint level [94]. An improvement in pain at rest after ankle injections has been described in patients with RA, and the injection of corticosteroids significantly improves pain, oedema and morning stiffness [93, 95].

Although corticosteroid injection is a method that significantly alleviates local inflammation, its adverse effects, such as local deterioration in repeated injections, should also be highlighted. Another intra-articular therapy could be the injection of hyaluronic acid, which has shown improvement in short-term foot function and reduction of pain [96, 97].

The use of anatomical landmarks for needle placement in injections is not always reliable and unanimous for all patients. One study predicted that one-third of ankle joint injections result in extra-articular localization [98]. Therefore, the use of ultrasound to perform injections is an essential aspect for the effect to occur in the desired place. The use of this technique improves results in the short term, with even greater success in the long term, enough to justify the additional cost of using imaging [99]. Previous studies indicate that after the injection of corticosteroids in patients with RA and foot pain, with and without ultrasound, the information provided by ultrasound helps to obtain better results in relation to the physical function [100] (Table 2).

Discussion

This study contributes to the field of rheumatology by presenting a comprehensive set of CPGs dedicated to the management of foot and ankle pathologies in RA patients. These guidelines fill a critical gap in the literature, offering detailed, evidence-based recommendations where previously there was a notable lack of specificity and depth, particularly in the context of non-pharmacological treatments. Consequently, recommendations that will help professionals and patients to manage podiatric pathologies derived from RA have been created.

The first joints affected by the disease are the small synovial joints, with the foot being one of the body regions with the highest incidence. Delayed management of the alterations causes a loss in foot functionality, which causes high levels of pain and increased disability, which ultimately translates into a decrease in the quality of life of the RA patient [1, 5, 6].

Currently, the pharmacological treatment of RA is chronic and modifiable, with drug doses being periodically adjusted according to the level of disease activity. Therefore, starting RA treatment as soon as possible is very important, ideally within the first 12 weeks from the onset of symptoms [101,102,103]. Likewise, it is vital to establish non-pharmacological treatment of the foot as soon as possible, but there are no evidence-based guidelines that health professionals can follow in this regard. This means that it is not possible to follow protocols that guide foot management in patients with RA. Some CPGs are available that offer recommendations to rheumatologists and other healthcare professionals involved in the care of RA patients in a holistic way, where some foot-related recommendations are available, but not focused on feet and lacking in depth [9, 10].

The importance of reducing the variability of clinical practice is mainly to avoid negative repercussions on the patient due to clinical misinterpretations, which may be related to inexperience, errors in the collection of data in medical records, and/or lack of resources and updating of knowledge of specialist professionals [11].

As strengthen, the creation of the current CPG presents a great advantage in the management of foot and ankle problems in patients with RA, being the first guide focused exclusively on the foot and ankle in RA. In addition, it should be noted that the perspective of patients with RA has been considered in the development of the CPG, both in the guideline group when developing the questions and in the review of the final manuscript. In this way, it is intended to improve the health, the ability to move autonomously, independence and therefore the functionality and quality of life of people affected by RA, with foot and ankle involvement, by establishing recommendations with high evidence. In addition, to reduce the variability in clinical practice among professionals in the diagnosis and treatment of foot and ankle involvement in patients with RA; to monitor the progress of foot and ankle involvement with the aim of carrying out preventive and early treatment and, finally, to improve the approach to foot and ankle problems in patients with RA, promoting rationality and efficiency in the choice of different treatments.

It is also necessary to point out the limitation that this guide presents in relation to the scarcity of articles of high evidence to answer some of the questions initially proposed. This was solved by recruiting a role of experts who contributed with their clinical and research experience.

In the process of developing this guide, some priority areas for future research have been identified:

-

Effects of physical exercise on the feet of RA patients, including their level of pain, disability, and quality of life.

-

Clinical trials in deficit areas such as foot surgery, patient self-care or chiropodies.

-

To work to educate the health care professionals involved in the foot therapies of these patients.

With the recommendations presented in this paper, professionals will be better guided through the best management strategies for the foot and ankle pathologies of the RA patient. Furthermore, the information outlined in this guide can be used to generate information which can be passed onto RA patients.

Conclusion

Our study culminates in evidence-based recommendations for foot and ankle management in rheumatoid arthritis patients, highlighting the utility of chiropody, foot orthoses, and therapeutic footwear in reducing pain and enhancing mobility. Custom solutions are particularly emphasized for their role in improving quality of life. Surgical options are advised for cases refractory to conservative measures, aiming to preserve functionality. The importance of self-care and education in promoting independence is also underscored. These guidelines serve as a foundation for clinicians, emphasizing the need for ongoing research to refine and update therapeutic strategies.

References

Chan PJ, Kong KO (2013) Natural history and imaging of subtalar and midfoot joint disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 16:14–18

Stolt M, Suhonen R, Leino-Kilpi H (2017) Foot health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis—a scoping review. Rheumatol Int 37:1413–1422

Turner DE, Woodburn J (2008) Characterising the clinical and biomechanical features of severely deformed feet in rheumatoid arthritis. Gait Posture 28:574–580

Riente L, Delle Sedie A, Iagnocco A et al (2006) Ultrasound imaging for the rheumatologist V. Ultrasonography of the ankle and foot. Clin Exp Rheumatol 24:493–498

Göksel Karatepe A, Günaydin R, Adibelli ZH et al (2010) Foot deformities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the relationship with foot functions. Int J Rheum Dis 13:158–163

Louwerens JWK, Schrier JCM (2013) Rheumatoid forefoot deformity: pathophysiology, evaluation and operative treatment options. Int Orthop 37:1719–1729

Van Der Leeden M, Steultjens MPM, Terwee CB et al (2008) A systematic review of instruments measuring foot function, foot pain, and foot-related disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res off J Am Coll Rheumatol 59:1257–1269

Turner DE, Helliwell PS, Emery P, Woodburn J (2006) The impact of rheumatoid arthritis on foot function in the early stages of disease: a clinical case series. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 7:102. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-7-102

Álvaro-Gracia JM (2019) Guía De práctica clínica Para El manejo de pacientes con artritis reumatoide (GUIPCAR). Soc Española Reumatol Madrid Ed Doyma

Allen A, Carville S, McKenna F (2018) Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 362

Maese J, De Yébenes MJG, Carmona L et al (2012) Estudio Sobre El manejo de la artritis reumatoide en Espana (emAR II). Características clínicas De Los pacientes. Reumatol Clínica 8:236–242

Steinberg E, Greenfield S, Wolman DM et al (2011) Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. National Academies Press Washington, DC

Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS (1995) The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. Acp j club 123:A12–A13

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al (2010) 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 62:2569–2581. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.27584

Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T et al (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, Hoboken

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D et al (2000) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses

Bawor M, Dennis BB, Bhalerao A et al (2015) Sex differences in outcomes of methadone maintenance treatment for opioid use disorder: a systematic reviewand meta-analysis. C Open 3:E344–E351. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20140089

Ramos-Petersen L, Nester CJ, Reinoso-Cobo A et al (2020) A systematic review to identify the effects of biologics in the feet of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Med (B Aires) 57:23

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Coello PA, Rigau D, Solà I, Martínez García L (2013) La formulación de recomendaciones en salud: el sistema GRADE. In: Med. clín (Ed. impr.)

Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD et al (2013) GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 66:726–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.003

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R et al (2011) GRADE guidelines 6. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol 64:1283–1293

Menz HB, Zammit GV, Munteanu SE (2007) Plantar pressures are higher under callused regions of the foot in older people. Clin Exp Dermatology Clin Dermatology 32:375–380

Redmond AC, Waxman R, Helliwell PS (2006) Provision of foot health services in rheumatology in the UK. Rheumatology 45:571–576

Mochizuki T, Yano K, Ikari K et al (2020) Relationship of callosities of the forefoot with foot deformity, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, and joint damage score in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 30:287–292

Tada M, Koike T, Okano T et al (2015) Preference of surgical procedure for the forefoot deformity in the rheumatoid arthritis patients—A prospective, randomized, internal controlled study. Mod Rheumatol 25:362–366

Woodburn J, Helliwell PS (1996) Relation between heel position and the distribution of forefoot plantar pressures and skin callosities in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 55:806–810. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.55.11.806

Landorf KB, Morrow A, Spink MJ et al (2013) Effectiveness of scalpel debridement for painful plantar calluses in older people: a randomized trial. Trials 14:1–9

Siddle HJ, Redmond AC, Waxman R et al (2013) Debridement of painful forefoot plantar callosities in rheumatoid arthritis: the CARROT randomised controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol 32:567–574

Dahmen R, Buijsmann S, Siemonsma PC et al (2014) Use and effects of custom-made therapeutic footwear on lower-extremity-related pain and activity limitations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective observational study of a cohort. J Rehabil Med 46:561–567

Williams AE, Nester CJ, Ravey MI (2007) Rheumatoid arthritis patients’ experiences of wearing therapeutic footwear - A qualitative investigation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-8-104

Goodacre LJ, Candy FJ (2011) If I didn’t have RA I wouldn’t give them house room’: the relationship between RA, footwear and clothing choices. Rheumatology 50:513–517

Naidoo S, Anderson S, Mills J et al (2011) I could cry, the amount of shoes I can’t get into: a qualitative exploration of the factors that influence retail footwear selection in women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Foot Ankle Res 4:21

Tehan PE, Taylor WJ, Carroll M et al (2019) Important features of retail shoes for women with rheumatoid arthritis: a Delphi consensus survey. PLoS ONE 14:e0226906

Tenten-Diepenmaat M, van der Leeden M, Vliet Vlieland TPM et al (2018) The effectiveness of therapeutic shoes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 38:749–762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4014-4

Marsman AF, Dahmen R, Roorda LD et al (2013) Foot-related health care use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in an outpatient secondary care center for rheumatology and rehabilitation in the Netherlands: a cohort study with a maximum of fifteen years of followup. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 65:220–226

Webster J, Murphy D (2017) Atlas of orthoses and Assistive devices. Elsevier Health Sciences

Conrad KJ, Budiman-Mak E, Roach KE, Hedeker D (1996) Impacts of foot orthoses on pain and disability in rheumatoid arthritics. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1–7

Reina-Bueno M, Vázquez-Bautista M, del C, Pérez-García S et al (2019) Effectiveness of custom-made foot orthoses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 33:661–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518819118

Gatt A, Formosa C, Otter S (2016) Foot orthoses in the management of chronic subtalar and talo crural joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Foot 27:27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2016.03.004

Van der Leeden M, Fiedler K, Jonkman A et al (2011) Factors predicting the outcome of customised foot orthoses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. J Foot Ankle Res 4:8

Cameron-Fiddes V, Santos D (2013) The use of off-the-shelf foot orthoses in the reduction of foot symptoms in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Foot (Edinb) 23:123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foot.2013.09.001

Woodburn J, Barker S, Helliwell PS (2002) A randomized controlled trial of foot orthoses in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:1377–1383

Woodburn J, Hennessy K, Steultjens MP et al (2010) Looking through the window of opportunity: is there a new paradigm of podiatry care on the horizon in early rheumatoid arthritis? J. Foot Ankle Res 3:8

Santos D, Cameron-Fiddes V (2014) Effects of off-the-shelf foot orthoses on plantar foot pressures in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 104:610–616

Payne C, Oates M, Noakes H (2003) Static stance response to different types of foot orthoses. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 93:492–498

Tenten-Diepenmaat M, Dekker J, Heymans MW et al (2019) Systematic review on the comparative effectiveness of foot orthoses in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Foot Ankle Res 12:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-019-0338-x

Chalmers AC, Busby C, Goyert J et al (2000) Metatarsalgia and rheumatoid arthritis–a randomized, single blind, sequential trial comparing 2 types of foot orthoses and supportive shoes. J Rheumatol 27:1643

Grondal L, Hedstrom M, Stark A (2005) Arthrodesis compared to Mayo resection of the first metatarsophalangeal joint in total rheumatoid forefoot reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int 26:135–139

Ortega-Avila AB, Moreno-Velasco A, Cervera-Garvi P et al (2019) Surgical Treatment for the ankle and foot in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Clin Med 9:42

Donegan RJ, Blume PA (2017) Functional results and patient satisfaction of first metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis using dual crossed screw fixation. J Foot Ankle Surg 56:291–297

Fazal MA, Wong JH-M, Rahman L (2018) First metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis with two orthogonal two hole plates. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 52:363–366

Rosenbaum D, Timte B, Schmiegel A et al (2011) First ray resection arthroplasty versus arthrodesis in the treatment of the rheumatoid foot. Foot Ankle Int 32:589–594

Yano K, Ikari K, Inoue E et al (2018) Features of patients with rheumatoid arthritis whose debut joint is a foot or ankle joint: a 5,479-case study from the IORRA cohort. PLoS ONE 13:e0202427

Lee SW, Kim S-Y, Chang SH (2019) Prevalence of feet and ankle arthritis and their impact on clinical indices in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20:420. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-2773-z

Horita M, Nishida K, Hashizume K et al (2018) Outcomes of resection and joint-preserving arthroplasty for forefoot deformities for rheumatoid arthritis. Foot Ankle Int 39:292–299

Reize P, Leichtle CI, Leichtle UG, Schanbacher J (2006) Long-term results after metatarsal head resection in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Foot Ankle Int 27:586–590

Triolo P, Rosso F, Rossi R et al (2017) Fusion of the first metatarsophalangeal joint and second to fifth metatarsal head resection for rheumatoid forefoot deformity. J Foot Ankle Surg 56:263–270

Hirao M, Ebina K, Tsuboi H et al (2017) Outcomes of modified metatarsal shortening offset osteotomy for forefoot deformity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: short to mid-term follow-up. Mod Rheumatol 27:981–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1276512

van der Heide HJL, Schutte B, Louwerens JWK et al (2009) Total ankle prostheses in rheumatoid arthropathy: outcome in 52 patients followed for 1–9 years. Acta Orthop 80:440–444

Mousavian A, Baradaran A, Schon LC et al (2023) Total ankle replacement outcome in patients with inflammatory versus noninflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Spec 16:314–324

Orem DE, Vardiman EM (1995) Orem’s nursing theory and positive mental health: practical considerations. Nurs Sci Q 8:165–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/089431849500800407

Denyes MJ, Orem DE, Bekel G (2001) Self-Care: a foundational science. Nurs Sci Q 14:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/089431840101400113

Wang H-H, Shieh C, Wang R-H (2004) Self-care and well-being model for elderly women: a comparison of rural and urban areas. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 20:63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70086-5

Laitinen A-M, Pasanen M, Wasenius E, Stolt M (2022) Foot self-care competence reported by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. J Foot Ankle Res 15:93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-022-00599-4

Semple R, Newcombe LW, Finlayson GL et al (2009) The FOOTSTEP self-management foot care programme: are rheumatoid arthritis patients physically able to participate? Musculoskelet Care 7:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.142

Garrow a P, Papageorgiou a C, Silman a J et al (2000) Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess disabling foot pain. Pain 85:107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00263-8

Siddle HJ, Firth J, Waxman R et al (2012) A case series to describe the clinical characteristics of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 31:541–545

Fitzgerald P, Siddle HJ, Backhouse MR, Nelson EA (2015) Prevalence and microbiological characteristics of clinically infected foot-ulcers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective exploratory study. J Foot Ankle Res 8:38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-015-0099-0

Firth J, Hale C, Helliwell P et al (2008) The prevalence of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 59:200–205

Firth J, Waxman R, Law G et al (2014) The predictors of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 33:615–621

Vlieland TPMV, Pattison D (2009) Non-drug therapies in early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 23:103–116

Christie A, Jamtvedt G, Dahm KT et al (2007) Effectiveness of nonpharmacological and nonsurgical interventions for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of systematic reviews. Phys Ther 87:1697–1715. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20070039

Hurkmans E, van der Giesen FJ, Vlieland TPMV et al (2009) Dynamic exercise programs (aerobic capacity and/or muscle strength training) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Durcan L, Wilson F, Cunnane G (2014) The effect of exercise on sleep and fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled study. J Rheumatol 41:1966–1973

Dekker J, de Rooij M, van der Leeden M (2016) Exercise and comorbidity: the i3-S strategy for developing comorbidity-related adaptations to exercise therapy. Disabil Rehabil 38:905–909

Dantas GAF, Sacco ICN, Ferrari AV et al (2023) Effects of a foot-ankle muscle strengthening program on pain and function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Brazilian J Phys Ther 27:100531

Osthoff A-KR, Juhl CB, Knittle K et al (2018) Effects of exercise and physical activity promotion: meta-analysis informing the 2018 EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis and hip/knee osteoarthritis. RMD open 4:e000713

Schiffer T, Knicker A, Hoffman U et al (2006) Physiological responses to nordic walking, walking and jogging. Eur J Appl Physiol 98:56–61

de Jong Z, Munneke M, Zwinderman AH et al (2003) Is a long-term high‐intensity exercise program effective and safe in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum off J Am Coll Rheumatol 48:2415–2424

Shamus J, Shamus E, Gugel RN et al (2004) The effect of sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training on reducing pain and restoring function in individuals with hallux limitus: a clinical trial. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 34:368–376

Halstead J, Chapman GJ, Gray JC et al (2016) Foot orthoses in the treatment of symptomatic midfoot osteoarthritis using clinical and biomechanical outcomes: a randomised feasibility study. Clin Rheumatol 35:987–996

Munteanu SE, Landorf KB, McClelland JA et al (2021) Shoe-stiffening inserts for first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. Osteoarthr Cartil 29:480–490

Goldberg AJ, Zaidi R, Thomson C et al (2016) Total ankle replacement versus arthrodesis (TARVA): protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 6:e012716

Mølgaard CM, Rathleff MS, Andreasen J et al (2018) Foot exercises and foot orthoses are more effective than knee focused exercises in individuals with patellofemoral pain. J Sci Med Sport 21:10–15

Hu H, Xu A, Gao C et al (2021) The effect of physical exercise on rheumatoid arthritis: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 77:506–522

Oldham JA, Stanley JK (1989) Rehabilitation of atrophied muscle in the rheumatoid arthritic hand: a comparison of two methods of electrical stimulation. J Hand Surg Am 14:294–297

Stanton DEB, Lazaro R, MacDermid JC (2009) A systematic review of the effectiveness of contrast baths. J Hand Ther 22:57–70

Welch V, Brosseau L, Casimiro L et al (2002) Thermotherapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB (2016) Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet (London England) 388:2023–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30173-8

Gossec L, Dougados M (2004) Intra-articular treatments in osteoarthritis: from the symptomatic to the structure modifying. Ann Rheum Dis 63:478–482

Macarrón Pérez P, Morales Lozano M, del Vadillo Font R C, et al (2021) Multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of tendinous foot involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 40:4889–4897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05848-8

Furtado RNV, Machado FS, da Luz KR et al (2017) Intra-articular injection with triamcinolone hexacetonide in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: prospective assessment of goniometry and joint inflammation parameters. Rev Bras Reumatol 57:115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2016.08.001

Derendorf H, Möllmann H, Grüner A et al (1986) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glucocorticoid suspensions after intra-articular administration. Clin Pharmacol Ther 39:313–317

Lopes RV, Furtado RNV, Parmigiani L et al (2008) Accuracy of intra-articular injections in peripheral joints performed blindly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 47:1792–1794. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken355

Wang CC, Lee SH, Lin HY et al (2017) Short-term effect of ultrasound-guided low-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid injection on clinical outcomes and imaging changes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of the ankle and foot joints. A randomized controlled pilot trial. Mod Rheumatol 27:973–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1270496

Balazs EA (2003) Analgesic effect of elastoviscous hyaluronan solutions and the treatment of arthritic pain. Cells Tissues Organs 174:49–62. https://doi.org/10.1159/000070574

Jones A, Regan M, Ledingham J et al (1993) Importance of placement of intra-articular steroid injections. BMJ Br Med J 307:1329

Hall S, Buchbinder R (2004) Do imaging methods that guide needle placement improve outcome? Ann Rheum Dis 63:1007–1008

d’Agostino M-A, Ayral X, Baron G et al (2005) Impact of ultrasound imaging on local corticosteroid injections of symptomatic ankle, hind-, and mid-foot in chronic inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum 53:284–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21078

Sanmartí R, García-Rodríguez S, Álvaro-Gracia JM et al (2015) 2014 update of the Consensus Statement of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology on the Use of Biological therapies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Reumatol Clínica (English Ed 11:279–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reumae.2015.05.002

Nell VPK, Machold KP, Eberl G et al (2004) Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 43:906–914

Toledano E, de Yébenes MJG, González-Álvaro I, Carmona L (2019) Índices De gravedad en la artritis reumatoide: una revisión sistemática. Reumatol Clínica 15:146–151

Funding

Open access charge is provided by Universidad de Málaga/CBUA.

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad Málaga/CBUA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the study conception and design. Author Contributions: Conceptualization, LRP, GGN, ABOA, ARC JGC, JAB, RCT, JMMM, RCC, ST, and LCG. All authors contributed to the Literature Reviews. Methodology, LRP, GGN, JGC, LCG and ABOA. Writing—original draft, LRP, GGN, JAB, RCT and ABOA. Writing—review and editing, GGN, ABOA, LRP and RCC. All authors read and approved the final manuscript to the published version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos-Petersen, L., Reinoso-Cobo, A., Ortega-Avila, AB. et al. A clinical practice guideline for the management of the foot and ankle in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05633-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-024-05633-1