Abstract

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) are systemic necrotizing vasculitides associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Given the immunosuppression used to manage these conditions, it is important for clinicians to recognize complications, especially infectious ones, which may arise during treatment. Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphoangioproliferative neoplasm caused by human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8). Its cutaneous manifestations can mimic vasculitis. We describe a 77-year-old man with microscopic polyangiitis with pulmonary-renal syndrome treated with prednisone and intravenous cyclophosphamide who developed KS (HHV-8 positive) after 2 months of treatment. Cyclophosphamide was discontinued and prednisone gradually lowered with improvement and clinical stabilization of KS lesions. This comprehensive review includes all published cases of KS in patients with AAV, with a goal to summarize potential risk factors including the clinical characteristics of vasculitis, treatment and outcomes of patients with this rare complication of immunosuppressive therapy. We also expanded our literature review to KS in other forms of systemic vasculitis. Our case-based review emphasizes the importance of considering infectious complications of immunosuppressive therapy, especially glucocorticoids, and highlights the rare association of KS in systemic vasculitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) includes microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) (Wegener’s), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) (Churg-Strauss syndrome), all pauci-immune vasculitides which share clinical features and are characterized by the presence of ANCA [1]. Serious organ-threatening disease involvement with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage but also gastrointestinal, cardiac, and neurologic disease can occur [2]. The standard treatment for severe organ-threatening disease is glucocorticoids, followed by induction therapy with cyclophosphamide, or rituximab [3]. A serious consequence of immunosuppression is opportunistic infections. Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphoangioproliferative neoplasm that has been associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) [4,5,6]. Over the years, there have been four recognized types of KS: classic, endemic, iatrogenic (immunosuppression or transplant associated), and epidemic [4,5,6]. We report a case of hydralazine-induced AAV with pulmonary-renal syndrome complicated by iatrogenic KS during treatment. We performed a comprehensive search through MEDLINE using the following keywords: Kaposi sarcoma, vasculitis, ANCA vasculitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, Takayasu arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, and Behcet's disease. We included articles published in English so that details could be extracted. This resulted in exclusion of 5 non-English articles (1 case in AAV and 4 cases in giant cell arteritis). The references of the individual articles were also examined to find other key references. The aim of the review was to identify common factors which may better aid in identifying patients at risk of this rare complication. Based on our review, glucocorticoids appear to be an important risk factor for KS in patients with vasculitis.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old man of Italian American descent was referred to us for evaluation of AAV. He presented to an outside facility with a 30-lb weight loss, cough, scant hemoptysis, and worsening dyspnea on exertion. Laboratory evaluation showed acute kidney injury with a creatinine of 2.58 mg/dL (baseline 1.0 mg/dL) and BUN of 30 mg/dL, acute anemia with hemoglobin 6.1 g/dL. During hospitalization, he developed rapidly progressive renal failure requiring initiation of hemodialysis, in addition to gross hemoptysis. Serologies included a positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA 1:320), positive double-stranded DNA (dsDNA 1:40), p-ANCA of 1:1280, MPO 52 IU (> 1 IU positive), and negative anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody (Table 1). Other serologies including SSA, SSB, Smith, RNP, centromere, Scl-70, DRVVT, cardiolipin, beta-2-glycoprotein, ribosomal P, anti-chromatin antibodies were negative. Histone antibodies were not tested. Bronchoscopy confirmed diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. A kidney biopsy was done but was non-diagnostic, showing acute tubular necrosis and mild mesangial matrix expansion with 4 out of 13 glomeruli which were globally sclerotic with mild parenchymal scarring. The patient was treated for a diagnosis of MPA with pulse does steroids, seven sessions of plasmapheresis followed by intravenous cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2 during hospitalization. He was able to successfully come off hemodialysis after 1.5 weeks with a new baseline creatinine of 2 mg/dL. Four weeks later, he was treated with cycle 2 of intravenous cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2.

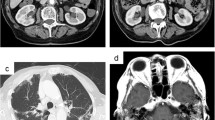

Approximately 2 months after starting treatment, he developed a new lower extremity rash (Fig. 1a). Prednisone was increased from 40 to 45 mg by his local rheumatologist with some improvement. However, given persistent symptoms, the patient sought a second opinion at our tertiary care medical center. At the time of evaluation, he was on prednisone 45 mg daily and last cyclophosphamide (dose 2, 400 mg/m2) infusion had been administered 2 weeks prior. Apart from the rash, he denied any symptoms. Laboratory parameters, including renal function, were stable. Medication review revealed that he had been on treatment with hydralazine for hypertension for more than 1 year prior, and, given association of hydralazine with AAV, hydralazine was discontinued. Prednisone was lowered to 35 mg. Rituximab was discussed given severe manifestations of vasculitis but given positive hepatitis B core antibody, recommendation was made for evaluation with infectious diseases first. Unfortunately, 1 month later, he was hospitalized for mental status changes from urosepsis with Escherichia coli bacteremia. He was on prednisone 35 mg daily at the time. Treatment was complicated with Clostridium difficile colitis. During that hospitalization, further testing was pursued (Table 1). In addition, given lack of improvement in the lower extremity rash, a skin biopsy was obtained from his left thigh and his left foot. This showed an atypical HHV8-positive vascular proliferation without vasculitis consistent with KS (Fig. 1b–d). Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative. While the initial plan was to start treatment with rituximab based on the severity of the manifestations of vasculitis, given the numerous infectious complications and hospitalizations, along with the absence of any evidence of active vasculitis, the recommendation was to hold off on immunosuppressive therapy. Furthermore, given that there was suspicion of this being hydralazine-induced, it was felt discontinuation of the trigger may also help. After discussion with the different specialists, and the patient, the decision was made to gradually taper prednisone and monitor closely without additional immunosuppressive therapy. He was also referred to oncology for co-management. He did not have any clinical evidence of gastrointestinal mucosal involvement of his KS and was started on treatment with topical imiquimod cream 5%. Chemotherapy was not considered since the etiology of his KS was felt to be due to immunosuppression as well as his recent history of multiple infections, renal insufficiency, and, immunosuppression was being lowered. He remains on prednisone 10 mg daily with adequate control of vasculitis and improvement in skin lesions. He continues to follow with rheumatology and oncology. Since discontinuation of cyclophosphamide and lowering prednisone, hypogammaglobulinemia has resolved with immunoglobulin G of 825 mg/dL (range 600–1540 mg/dl). He has had no further infectious complications and his KS remains clinically indolent.

a Multiple violaceous, coalescent, nodular lesions on the foot and ankle. b Histologic sections of skin from biopsy of a thigh lesion show dermis filled with irregular, somewhat jagged blood-filled vascular spaces adhering to collagen bundles and surrounding native blood vessels (so-called ‘promontory sign’, see arrows). Hematoxylin and eosin, 200x. c Performed CD34 immunohistochemistry strongly highlights irregular, infiltrative vascular spaces. CD34 immunohistochemistry, 200x. d Performed HHV8 immunohistochemistry highlights tumor endothelial cell nuclei and confirms the diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. HHV8 immunohistochemistry, 200x

Discussion

We present a rare case of MPA, possibly hydralazine-induced, with pulmonary-renal syndrome complicated by the development of KS during treatment with systemic glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide.

One of the unusual aspects of this case was the possibility of the manifestations of AAV being hydralazine-induced. Severe manifestations including pulmonary-renal syndrome have been described in hydralazine-induced vasculitis [7,8,9,10,11,12]. A clue to this entity is the serologic profile which often includes other antibodies often seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (which hydralazine can also induce) in addition to ANCA (usually p-ANCA, MPO) [12]. Other positive serologies that have been reported with hydralazine-induced vasculitis are ANA, anti-histone antibodies, positive dsDNA, hypocomplementemia and anti-phospholipid antibodies [9, 12]. Our patient also had positive ANA and low titer dsDNA at initial diagnosis. While other connective tissue disease serologies, complements and testing for anti-phospholipid antibodies was performed, anti-histone antibody was not tested. The possibility of hydralazine-induced vasculitis was missed and considered few months later when he was evaluated at our facility for a second opinion. In most cases of serious organ manifestations, even though hydralazine was thought to be the trigger, in addition to withdrawal of the offending medication, immunosuppressive therapy including glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide or rituximab were used [7]. In our case, the management was complicated by numerous infectious complications including KS.

The risk factors for KS include infection with HHV8, HIV, and immunosuppression [4,5,6, 13,14,15]. Our patient best fits as an example of iatrogenic KS, which has been widely reported in immunosuppressed patients, including those with organ transplantation [5, 16]. Despite the wide-spread use of immunosuppressive medications in systemic rheumatic diseases including vasculitis, the association of KS is rare, indicating there are other risk factors at play [17, 18].

A review of the literature evaluating KS in AAV, identified 10 additional cases whose findings are summarized in Table 2 [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. The majority of the reports (70%) are in patients with GPA, with two reports in MPA and one in EGPA (Table 2). Age range was from 46 to 78 years with 60% of the cases being in men (Table 2). Time to onset of KS lesions ranged from 6 weeks to 11 months (Table 2). One reported case in the literature described coincidental occurrence of KS and GPA with worsening KS during treatment [26]. In another report, KS lesion on an ear was noted 19 years after diagnosis but, unusually, this patient had been given several different inflammatory diagnoses over the years including polyarteritis nodosa, neurosarcoidosis and finally, GPA [19]. All patients were still on systemic glucocorticoids and intravenous methylprednisolone were administered in 80% reported cases (Table 2). Adjunctive immunosuppressive therapy in patients who developed KS included cyclophosphamide (9 cases), azathioprine (3 cases) and mycophenolate mofetil (1 case), likely reflecting commonly used treatments in AAV given most cases had pulmonary and renal manifestations (Table 2). In all except one case, cutaneous involvement from KS was present, most frequently on the trunk and extremities. One case reported isolated KS of the gastrointestinal tract in a patient with GPA [28]. HHV-8 was positive in 6 of 7 cases where the information was provided (Table 2). The majority of cases improved with reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy, especially glucocorticoids (Table 2). In some cases, chemotherapy and radiation therapy were also used to treat KS (Table 2). The status of the vasculitis after lowering immunosuppressive therapy was variable with some cases of relapses (Table 2). The patient in this case also presented many management challenges. Though hydralazine was thought to be the likely trigger of vasculitis, given the severe manifestations with pulmonary-renal syndrome, treatment with rituximab was considered. However, the patient had positive hepatitis B core antibody and recommendation was to start prophylaxis prior to treatment. Meanwhile, he developed numerous infectious complications including urosepsis, Clostridium difficile requiring hospitalizations which delayed initiation of rituximab. Finally, he also developed infectious complication of KS from HHV-8. Given that there was no evidence of active vasculitis, that hydralazine which may have been a trigger was discontinued, and risks of further immunosuppression, decision was made to use glucocorticoid monotherapy, lower prednisone gradually monitor closely. He clinically improved with reduction in glucocorticoid doses, discontinuation of cyclophosphamide, and topical imiquimod. To date, there has been no recurrence of vasculitis which may be in part from the discontinuation of hydralazine.

Given the rarity of KS in AAV, we also extended our literature review to other forms of systemic vasculitis (Table 3). We found reports in giant cell arteritis (4 cases), Behcet’s disease (2 cases), polymyalgia rheumatica (3 cases), IgA vasculitis (previously Henoch-Schonlein purpura, 1 case), and cutaneous vasculitis (1 case) [17, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. In all cases, patients were on glucocorticoid therapy (Table 3). As in the case of patients with AAV, cutaneous involvement from KS was present, most frequently on the trunk and extremities. There was a case of systemic involvement with KS of the gastrointestinal tract in a patient with Behcet’s disease [34]. The majority of cases improved with reduction or withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy, especially glucocorticoids, with some relapses of the underlying vasculitis in some cases (Table 3).

Both the cellular and humoral arms of the immune system have been implicated in the control of KS. Immunosuppression is a common theme noted in KS, whether due to innate problems of host immunity, or, due to factors that lead to induced immunosuppression [38]. For instance, the rate of KS in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients is inversely proportional to the CD4 count [38]. In non-AIDS associated KS, based on our review of the literature, in patients with rheumatic conditions, glucocorticoids appear to be a consistent risk factor for KS irrespective of other immunosuppressive therapy [39]. Several potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association of KS from immunosuppression, including higher expression of chemokine receptors and growth factors, or culprit viral genes. However the data is limited and information is extrapolated from the post-transplantation KS literature [40]. Other possibilities could be the effects of glucocorticoids on lymphocyte depletion [22]. Some studies have found a direct effect of glucocorticoids in stimulating the development and growth of KS [41, 42]. Exogenous glucocorticoids can stimulate the proliferation of spindle cells in KS by upregulation of glucocorticoid receptors [41, 42]. They can also cause direct activation of HHV-8 [41, 42].

Finally, B-cells are latent reservoirs of HHV-8 [6]. While all reported cases of KS in AAV to date have been in patients treated with cyclophosphamide, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, how the increased use of rituximab will affect risk of KS in AAV remains unclear. A recent report included 5 patients who developed KS after treatment with rituximab for their autoimmune conditions (none with AAV) [43]. All were on treatment with glucocorticoids (prednisone dose 10 mg to 35 mg). Time from rituximab to HHV-8 ranged from 3 to 11 months. Four of 5 patients had cutaneous manifestations but gastrointestinal, lung, urogenital disease, pleural effusion and lymphoma were also reported [43]. Two patients required treatment with radiation or chemotherapy [43].

In summary, despite immunosuppression in vasculitis, KS appears to be a rare complication of therapy. It is important to recognize KS as an infectious complication in patients with AAV. The violaceous, nodular lesions in KS, can be mistaken for the palpable purpura from cutaneous vasculitis which also affect the upper and lower extremities [44]. The majority of the cases were within the first year of treatment and the skin was the most frequently affected organ in KS. Glucocorticoid therapy appears to be an important risk factor. Lowering immunosuppression, especially glucocorticoids appears to be beneficial in causing regression of KS. However, this can be challenging since decreasing immunosuppression to help KS could potentially result in recurrence of the underlying systemic vasculitis. A multi-disciplinary approach is important along with individualizing the decision to lower immunosuppression with the possibility of relapse of vasculitis.

References

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA et al (2013) 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.37715

Seo P, Stone JH (2004) The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides. Am J Med 117:39–50

Specks U, Merkel PA, Seo P et al (2013) Efficacy of remission-induction regimens for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 369:417–427. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1213277

Vangipuram R, Tyring SK (2019) Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol 58:538–542

Antman K, Chang Y (2000) Kaposi’s sarcoma. N Engl J Med 342:1027–1038

Dittmer DP, Damania B (2016) Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: Immunobiology, oncogenesis, and therapy. J Clin Invest 126:3165–3175

Aeddula NR, Pathireddy S, Ansari A, Juran PJ (2018) Hydralazine-associated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis with pulmonary-renal syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-227161

Battisha A, Doughem K, Sheikh O et al (2020) Hydralazine-induced ANCA associated vasculitis (AAV) presenting with pulmonary-renal syndrome (PRS): a case report with literature review. Curr Cardiol Rev. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403x16666200518092814

Dobre M, Wish J, Negrea L (2009) Hydralazine-induced ANCA-positive pauci-immune glomerulonephritis: a case report and literature review. Ren Fail 31:745–748. https://doi.org/10.3109/08860220903118590

Timlin H, Liebowitz JE, Jaggi K, Geetha D (2018) Outcomes of hydralazine induced renal vasculitis. Eur J Rheumatol 5:5–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2017.17075

Yokogawa N, Vivino FB (2009) Hydralazine-induced autoimmune disease: comparison to idiopathic lupus and ANCA-positive vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol 19:338–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10165-009-0168-y

Kumar B, Strouse J, Swee M et al (2018) Hydralazine-associated vasculitis: overlapping features of drug-induced lupus and vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 48:283–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.01.005

Brown EE, Whitby D, Vitale F et al (2006) Virologic, hematologic, and immunologic risk factors for classic Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer 107:2282–2290. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22236

Goedert JJ, Vitale F, Lauria C et al (2002) Risk factors for classical Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 94:1712–1718. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/94.22.1712

Rezza G, Andreoni M, Dorrucci M et al (1999) Human herpesvirus 8 seropositivity and risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma and other acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related diseases. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:1468–1474. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/91.17.1468

Casoli P, Tumiati B (1992) Rheumatoid arthritis, corticosteroid therapy and Kaposi’s sarcoma: a coincidence? A case and review of literature. Clin Rheumatol 11:432–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02207213

Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT (1978) Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. A 5-year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer 42:2626–2630. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197812)42:6%3c2626::AID-CNCR2820420618%3e3.0.CO;2-7

Louthrenoo W, Kasitanon N, Mahanuphab P et al (2003) Kaposi’s sarcoma in rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:326–333. https://doi.org/10.1053/sarh.2002.50000

Hoff M, Rødevand E (2005) Development of multiple malignancies after immunosuppression in a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Rheumatol Int 25:238–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-004-0551-0

Ben FL, Rais L, Mebazza A et al (2013) Kaposi’s sarcoma with HHV8 infection and ANCA-associated vasculitis in a hemodialysis patient. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 24:1199–1202. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.121285

Erban SB, Sokas RK (1988) Kaposi’s sarcoma in an elderly man with wegener’s granulomatosis treated with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med 148:1201–1203. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1988.00380050205028

Deschenes I, Dion L, Beauchesne C, De Brum-Fernandes AJ (2003) Kaposi’s sarcoma following immune suppressive therapy for Wegener’s granulomatosis. J Rheumatol 30:622–624

Bouattar T, Kazmouhi L, Alhamany Z et al (2011) Kaposi’s sarcoma following immunosuppressive therapy for vasculitis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 22:319–323

Berti A, Scotti R, Rizzo N et al (2015) Kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis while taking mycophenolate mofetil. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 3:431–432

Saxena A, Netchiporouk E, Al-Rajaibi R et al (2015) Iatrogenic Kaposi’s sarcoma after immunosuppressive treatment for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s). JAAD Case Rep 1:71–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2014.12.002

Tas Kilic D, Karaahmetoglu Ozkan S, Canbakan B, Dundar N (2016) Kaposi’s sarcoma concurrent with granulomatosis polyangiitis. Eur J Rheumatol 3:85–86. https://doi.org/10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0027

Biricik M, Eren M, Bostan F et al (2019) Kaposi sarcoma development following microscopic polyangiitis treatment. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 30:537–539. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-2442.256864

Endo G, Nagata N (2020) Corticosteroid-induced Kaposi’s sarcoma revealed by severe anemia: a case report and literature review. Intern Med 59:625–631. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.3394-19

Leung F, Fam AG, Osoba D (1981) Kaposi’s sarcoma complicating corticosteroid therapy for temporal arteritis. Am J Med 71:320–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(81)90135-2

di Giacomo V, Nigro D, Trocchi G et al (1987) Kaposi’s sarcoma following corticosteroid treatment for temporal arteritis—a case report. Angiology 38:56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/000331978703800108

Schulhafer EP, Grossman ME, Fagin G, Bell KE (1987) Steroid-induced kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient with pre-AIDS. Am J Med 82:313–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(87)90076-3

Soria C, González-Herrada CM, García-Almagro D et al (1991) Kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient with temporal arteritis treated with corticosteroid. J Am Acad Dermatol 24:1027–1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(08)80128-4

Vincent T, Moss K, Colaco B, Venables PJW (2000) Kaposi’s sarcoma in two patients following low-dose corticosteroid treatment for rheumatological disease [6]. Rheumatology 39:1294–1296

Kötter I, Aepinus C, Graepler F et al (2001) HHV8 associated Kaposi’s sarcoma during triple immunosuppressive treatment with cyclosporin A, azathioprine, and prednisolone for ocular Behçet’s disease and complete remission of both disorders with interferon α. Ann Rheum Dis 60:83–86. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.1.83

Kuttikat A, Joshi A, Saeed I, Chakravarty K (2006) Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with giant cell arteritis. Dermatol Online J 12:16

Mezalek ZT, Harmouche H, El AN et al (2007) Kaposi’s sarcoma in association with Behcet’s disease: case report and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 36:328–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.11.001

Brambilla L, Esposito L, Nazzaro G, Tourlaki A (2017) Onset of Kaposi sarcoma and Merkel cell carcinoma during low-dose steroid therapy for rheumatic polymyalgia. Clin Exp Dermatol 42:702–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.13151

Cesarman E, Damania B, Krown SE et al (2019) Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0060-9

Louthrenoo W (2015) Treatment considerations in patients with concomitant viral infection and autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 29:319–342

Hosseini-Moghaddam SM, Soleimanirahbar A, Mazzulli T et al (2012) Post renal transplantation Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, clinical aspects, and therapy. Transpl Infect Dis 14:338–345

Guo WX, Antakly T (1995) AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: evidence for direct stimulatory effect of glucocorticoid on cell proliferation. Am J Pathol 146:727–734

Hudnall SD, Rady PL, Tyring SK, Fish JC (1999) Hydrocortisone activation of human herpesvirus 8 viral DNA replication and gene expression in vitro. Transplantation 67:648–652. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199903150-00002

Périer A, Savey L, Marcelin AG et al (2017) De novo human herpesvirus 8 tumors induced by rituximab in autoimmune or inflammatory systemic diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol 69:2241–2246. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40217

Yaqub S, Stepenaskie SA, Farshami FJ et al (2019) Kaposi sarcoma as a cutaneous vasculitis mimic: diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 12:23–26

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the authors made contributions to the content of this article. The literature review and initial draft of the manuscript were prepared by BT and TK. Clinical and histopathologic images were provided by AS and GS. All authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted and take full responsibility for all aspects of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the patient.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiong, B.K., Singh, A.S., Sarantopoulos, G.P. et al. Kaposi sarcoma in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 41, 1357–1367 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04810-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04810-w