Abstract

Emerging evidence exists that an altered gut microbiota is a key factor in the pathophysiology of a variety of diseases. Consequently, microbiota-targeted interventions, including administration of probiotics, have increasingly been evaluated. Mechanisms on how probiotics contribute to homeostasis or reverse (effects of) dysbiosis remain yet to be elucidated. In the current study, we assessed the effects of daily Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (LcS) ingestion in healthy children aged from 12–18 years on gut microbiota compositional diversity and stability. Results were compared to healthy children without LcS exposure. For a period of 6 weeks, fecal samples were collected weekly by both groups. In total, 18 children were included (6 probiotics; 12 non-probiotics). At 1-week intervals, no differences in diversity and stability were observed in children exposed to LcS versus controls. LcS ingestion by healthy children does not result in a more diverse and stable gut microbiota composition. Large double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials in children should be performed to gain more insight on potential beneficial health consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past decade, evidence has emerged on the associations between the microbiota and the pathophysiology of a variety of diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [1], irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [2], late onset sepsis (LOS) [3], and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) [4]. Therefore, the gut microbiota can be considered as a potential diagnostic biomarker, but also as a potential therapeutic target. Probiotics have been demonstrated to be effective in preventing the development of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile infections [5]. In addition, probiotics have been shown to be effective in the prevention of NEC in preterm born infants, although data are conflicting [6]. Over the years, the effectiveness of different probiotic strains has been studied, particularly strains from the genera Bifidobacterium, Saccharomyces, and Lactobacillus [7]. It has been presumed that health benefits are strain-specific, in which functional properties of one strain cannot be extrapolated to other strains [8]. To date, optimal probiotic strains and concentrations for the prevention and treatment of different diseases have not yet been established. Accumulated evidence is provided that supplemented probiotic strains are not incorporated in an individual’s microbiota and, consequently, possible effects disappear after discontinuation [9].

In daily practice, probiotics are used as a food supplement taken by individuals who are not ill, but hope to retain health by taking probiotic supplements in the form of probiotic yoghurts and dairy beverages [10, 11]. To date, however, studies on the effects of probiotics have largely focused on the ability of probiotics to modulate a diseased state towards a healthy state. Interpretation of effects of probiotics on microbiota and clinical symptoms in diseased populations can be complicated by the concomitant use of medication and the course of disease, both influencing microbiota composition. One of the underlying hypotheses is that probiotics could aid in retaining health by stabilizing the gut microbiota, thereby reducing the risk of microbial shifts towards an undesirable composition. Studies on the effects of probiotics, particularly on microbiota composition and dynamics in healthy state, are very limited. Increased knowledge on the effects of probiotics on gut microbiota diversity and stability in healthy populations could possibly lead to a more scientifically-based approach and targeted administration of probiotics in diseased populations. For example, studies on the effects of probiotics containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota (LcS) on gut microbiota diversity and stability in healthy state are scarce, while therapeutic effects of LcS have been assessed in patients with antibiotics associated diarrhea and functional constipation in several studies, although underlying mechanisms, optimal dosage and duration of administration of LcS remain unclear [12,13,14]. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effect of daily ingestion of a fermented milk product containing LcS on the gut microbiota composition, diversity, and short-term dynamics in a healthy pediatric population, compared to healthy children without probiotic exposure.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The current study was embedded in a study in which gut microbiota composition, diversity, and stability in a population of healthy children was studied [15]. In that study, 63 children aged from 2 to 18 years and visiting primary and secondary schools in the Netherlands collected a fecal sample weekly, for a period of 6 weeks and a follow-up sample after 18 months. It was observed that the microbial stability in children varied per phylum, at both short-term and long-term intervals. For the current study, six healthy volunteers aged 12–18 years, who were recruited for the previous study, were instructed to daily ingest probiotics containing LcS during 6 weeks. Effects on composition, diversity and stability of the gut microbiota were assessed. These children were recruited in the same inclusion period, from the same region and collection and analysis of the samples was performed in similar time intervals as the study in which the current study was embedded [15]. Exclusion criteria were the use of antibiotics, probiotics, or immunomodulating agents within 6 months prior to inclusion, culture-proven infectious gastroenteritis 6 months prior inclusion, history of gastrointestinal surgery (except appendectomy), or a diagnosis of a chronic gastrointestinal disease, including functional constipation, celiac disease, IBS, IBD, or short bowel syndrome, which were similarly for children on probiotics and controls. All participants were asked to complete a questionnaire on the following items: age, length, weight, area of inclusion (i.e., agriculture or urban), mode of delivery, pregnancy duration, neonatal feeding mode (i.e., breastfed or formula fed), duration of breastfeeding (if applicable), antibiotic use in the first year of life and medication use during 6 months prior to inclusion and during the study period.

Microbial results of the six included children on LcS were compared to results of 12 children without probiotics from the original cohort of 63 children. It was chosen to include twelve participants (1:2 case–control) to enlarge population size. Participants were matched based with respect to area of inclusion, antibiotics use in the first year of life, feeding mode in the neonatal period and mode of delivery. Participants of both subgroups were not matched based on age, since the assumption that the influence of age on gut microbiota composition is limited after the age of 8 years is previously demonstrated [15]. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of VU university Medical Center and informed consent was obtained from all study participants and parents in case of children aged under 16 years.

Probiotics

The probiotic used was a commercially available fermented milk product containing LcS at a minimum concentration of 6.5 × 109 viable cells per 65 mL bottle. The fermented milk was made out of skimmed milk powder, sugar, glucose, and water. The bottles contained 0.8 g proteins, 12 g carbohydrates, <0.1 g fat, and 10 g sugar, providing 50 kcal of energy. Probiotics were taken daily, during breakfast.

Sample Collection

Collection and analysis of the fecal samples of both studies was performed in the same period. All study participants were asked to collect a fecal sample (approximately 2 grams) in a sterile container (Stuhlgefäß 10 mL, Frickenhausen, Germany) on a weekly basis for a period of 6 weeks. To increase adherence, subjects were instructed to take the probiotics at a fixed moment of the day and to collect the fecal sample at the end of the week. Fecal samples were stored in the freezer (−20 °C) at home within 1 h after collection. Participants were asked to bring the frozen samples in a cooled condition to the outpatient ward of Amsterdam UMC location VUmc.

DNA Extraction and Sample Preparation

Samples were processed in line with an earlier conducted study [15]. First, DNA was extracted from fecal samples and one sample of the fermented milk product (200 µl) with the easyMag extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biomérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Approximately 100-400 mg feces was placed in an Eppendorf tube with 200 µl of nucliSens lysis buffer and subsequently vortexed. While shaking for 5 min, tubes were incubated at room temperature. After centrifugation (13,000 rmp; 2 min), 100 µl supernatant was transferred to an easyMag isolation container containing 2 ml nucliSens lysis buffer. This suspension was incubated for 10 min at room temperature, after which 70 µl of magnetic silica beads were added. The easyMag automated DNA isolation machine was used following the “specific A” protocol, eluting DNA in 110 µl buffer. All fecal samples were analyzed by intergenic spacer profiling (IS-pro).

Data Analysis

IS-Pro

Preprocessing was carried out with the IS-Pro proprietary software suite (Is-Diagnostics) and resulted in microbial profiles, as has been done in previous study [15]. Three levels of information were obtained: color of peaks sorts species into the phyla Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobia (FAFV), Bacteriodetes, and Proteobacteria, which are the main phyla present in the human gastrointestinal tract [16]. Length of the 16S-23S rDNA IS-region, displayed by number of nucleotides, can subsequently be used to identify bacteria at species level. Specific peak height, measured in relative fluorescence units, reflect the quantity of PCR product. To further analyze the obtained data, each peak in a profile was considered as an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) and its corresponding intensity as its abundance. Species determination of IS-Pro peaks was done by matching of profiles to a database of IS profiles of known bacterial species.

Diversity and Stability Analysis

The microbial diversity and stability analyses were performed on the IS-pro data. The Shannon diversity index was used as an indicator for the microbial diversity, and was based on the resulting profiles by conventional statistics. The Shannon diversity index was calculated per phylum and for overall microbial composition (by pooling the phyla FAFV, Bacteriodetes, and Proteobacteria). Diversity analysis was performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA). The data were visualized by using Spotfire software package (Tibco, Palo, Alto, CA, USA). The gut microbiota compositional stability was defined as intra-individual resistance to change in relative abundances of species over time, quantified by cosine distance (lower distance value represents higher stability). The cosine distance was expressed as a percentage value, for example, when two fecal samples of one individual collected over time would have identical microbial composition; compositional stability was considered to be 100%. The gut microbiota compositional stability of the participants through time was estimated by comparing all intervals per individual (i.e., for 1 week stability, all 1-week intervals were compared). Sample compositions were compared by calculating cosine distances for log2-transformed data per phylum and for the phyla FAFV, Bacteriodetes, and Proteobacteria combined, as has been done in previous studies [15, 16].

Demographics

All statistical analysis were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, USA). Demographic and clinical data were compared by an independent t test, Mann–Whitney U test or Chi Square test, where considered appropriate. Results were considered significant at a P value <0.05.

Results

Participants

In total, eighteen participants were included; six children who ingested probiotics and twelve children without probiotics intake. Characteristics of both study groups are depicted in Table 1. Notably, there was no medication use during the study period in both groups. The probiotics group consisted of children with a median age of 13 years, whereas the children in the non-probiotics group were younger (P value = 0.03). Consequently, a statistically significant difference was found between both groups in Body Mass Index (BMI); median BMI was higher in the probiotics group compared to the non-probiotics group (P value 0.05).

Lactobacillus casei Strain Shirota Abundance

In the probiotics group, the administered probiotic strain LcS was not detectable in any of the fecal samples analyzed at all predefined time points. Analysis of the fermented milk product by the same IS-pro technique showed that the fermented milk indeed contained the bacterial strain LcS.

Diversity and Stability

No difference was observed in Shannon diversity index in the probiotics group compared to the non-probiotics group at six predefined time points (week 1–6). This observation accounted for all different individual phyla, and was also observed when all phyla were combined (Fig. 1). To enlarge sample size per analysis, a post hoc analysis was performed, in which Shannon diversity indices from all six time points were pooled for both study groups. For this post hoc analysis a linear mixed model was applied. This did not result in a statistically significant difference in diversity index between both study groups (Bacteriodetes P value = 0.065; FAFV P value 0.071; Proteobacteria P value = 0.847).

Shannon diversity indices at different time points (t 1–6 correspond with sampling number in weeks), for the phyla Bacteriodetes (red), FAFV (blue), Proteobacteria (yellow). Dots represent the Shannon diversity index of each subject. No difference was observed in the probiotics group compared to the non-probiotics group at six predefined time points (Color figure online)

No difference was observed in 1-week stability between the probiotics and non-probiotics group (Fig. 2) (all bacteria combined P value = 0.57, Bacteriodetes P value = 0.51, FAFV P value = 0.45, Proteobacteria P value = 0.48). This was observed both for the total gut microbiota, as for the phyla Bacteriodetes, FAFV, and Proteobacteria separately.

Compositional stability for children with probiotics (blue) and without probiotics (red) exposure, expressed by cosine distance between sequential samples (higher values represent higher stability). Every subject is represented by five dots, since each subject collected six samples with 1-week intervals, therefore allowing for analysis of five 1-week stability measurements (for each subject, week one was compared with week 2, week 2 with week 3, etc.). No difference in compositional stability for all phyla combined and for each different phylum was seen between both study groups (Color figure online)

Discussion

In the current study, we examined the effect of LcS ingestion on gut microbial stability and diversity in a healthy pediatric population. We demonstrated that daily ingestion of LcS did not result in a higher diversity and stability of the microbiota composition for all phyla, when compared to the control group.

Several studies have assessed the effect of ingestion of LcS in different diseases, such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea [13], functional constipation [14], and NEC [17], with positive results. A study by Wang and colleagues, the effect of daily ingestion of LcS on the microbial compositional diversity and stability in children, was assessed [9]. In this study, it was demonstrated that daily ingestion of LcS resulted in increased levels of Bifidobacterium and total Lactobacillus, and a decrease of Enterobacteriacaea, Staphylococcus, and Clostridium perfringens. However, in this study, no control group was included, thereby limiting the ability to draw firm conclusions on the effect of LcS ingestion.

The gut microbiota composition is known to be influenced by numerous factors, such as dietary intake, infections, medication, and area of residence [18, 19]. An undisturbed colonization in early life is related to health in later life, possibly by shaping the immune system [20]. Because low microbial diversity has been linked to various diseased states, manipulation of the microbiota towards a more diverse state has been suggested to be beneficial for the host. However, the evidence for this strategy, besides in the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection, is still weak [21]. In previous studies, a positive correlation was described between the microbial diversity and stability [9, 15]. Recently, a mathematical algorithm was presented which explains the positive correlation between diversity and stability of the gut microbiota [22]. Here, it was demonstrated that higher species diversity leads to higher resilience within small microbiological ecosystems, and therefore results in a more stable system. Interestingly, a study focusing on the role of probiotics in the treatment of diarrhea-dominant IBS demonstrated that the gut microbiota composition in antibiotic-treated patients was more stable during ingestion of probiotics, compared to controls [23]. In healthy state, the phyla Bacteriodetes and FAFV have been characterized as phyla with highest diversity, and, possibly as a result, highest stability indices [24]. In the current study, no difference was observed in the diversity indices. However, in the current study, a small sample was used; therefore, additional studies are mandatory to assess the effect of probiotics on the diversity indices in a healthy pediatric population.

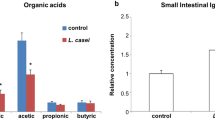

In previous studies, it has been demonstrated that the administration of LcS probably affects the gut microbiota composition indirectly, since LcS ingestion influenced abundancies of other strains, rather than an isolated increase in LcS concentrations [9]. Several different mechanisms explaining effects of probiotics have been described, such as immune modulation, the production of lactic acid (consequently reducing local pH), and competitive adhesion or displacement of pathogenic bacteria [25,26,27,28,29]. Studies have reported the advantages on health status of acetic acid produced by intestinal commensals, such as Bifidobacteria, which is known to have a bactericidal activity against various pathogenic Gram-negative bacilli [30,31,32]. Long-term ingestion of LcS has been reported to increase the population levels of indigenous Bifidobacteria as well as the fecal concentration of the organic acid levels [33, 34]. In the current study, it has not been demonstrated that LcS ingestion results in a different gut microbiota composition. This could be explained by the sample size, which might not have been sufficient enough to demonstrate potential differences in microbiota composition as has been described earlier. Therefore, not only larger studies are needed, but also additional analyses on bacteria-derived metabolites, which could provide more insight on the mechanisms underlining the effect of LcS on the gut microbiota composition and function.

One of the strengths of the current study is the inclusion of a non-intervention group, allowing for comparison of diversity and stability indices, which are known to fluctuate on short-term intervals, even in healthy state. Another strength was the collection of samples at six time points, allowing for accurate determination of short-term dynamics, in which no significant differences were observed between different time points. In addition, samples were analyzed by means of IS-pro, a molecular microbiota detection technique, which, in contrast to culturing techniques, allows for the identification of the highly complex intestinal microbiota down to species level [15, 16].

This study also has limitations. First, there were no baseline or follow-up measurements prior to or after cessation of LcS ingestion. By including these samples, the effect of daily LcS ingestion on diversity and stability could have been evaluated with more certainty. In addition, by including a sample after probiotics ingestion is ceased, the long-term effect after LcS ingestion could have been evaluated. Another limitation is that participants were not matched based on age. However, in a previous study it was demonstrated in the same population that from the age of 4–18 years, no age-related statistically significant differences in microbial composition were present [15]. Additionally, participants did not record their daily food intake, since detailed understanding of the influence of day-to-day changes in diet on temporal microbial dynamics would need a cohort consisting of at least hundreds of subjects [35, 36]. Therefore, we considered the current series of subjects being too small to perform suitable statistical analysis addressing the influence of diet. The influence of LcS ingestion on gut microbiota composition was assessed by analyzing fecal samples, which is consider to be mainly a reflection of the large intestinal microbiota composition [37,38,39]. Consequently, little can be said about the effect of LcS ingestion on the small intestinal microbiota composition based on fecal microbiota analyses. However, it has been reported that there is a low bacterial diversity and abundance in the small intestine of healthy individuals [40].

Conclusions

In the current study, we have explored the effect of ingestion of the probiotic strain LcS on the gut microbiota composition and dynamics in healthy children. There was no higher diversity and stability of the microbiota composition for any phyla after daily LcS ingestion. However, additional studies are needed with a larger cohort in a randomized controlled study design to validate current results.

References

Sheehan D, Moran C, Shanahan F (2015) The microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol 50(5):495–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-015-1064-1

Bennet SM, Ohman L, Simren M (2015) Gut microbiota as potential orchestrators of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver 9(3):318–331. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14344

Mai V, Torrazza RM, Ukhanova M, Wang X, Sun Y, Li N, Shuster J, Sharma R, Hudak ML, Neu J (2013) Distortions in development of intestinal microbiota associated with late onset sepsis in preterm infants. PLoS ONE 8(1):e52876. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052876

Patel RM, Denning PW (2015) Intestinal microbiota and its relationship with necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatr Res 78(3):232–238. https://doi.org/10.1038/pr.2015.97

Pattani R, Palda VA, Hwang SW, Shah PS (2013) Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Med 7(2):e56–e67

AlFaleh K, Anabrees J (2014) Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Evid Based Child Health 9(3):584–671. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1976

Wallace B (2009) Clinical use of probiotics in the pediatric population. Nutr Clin Pract 24(1):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533608329298

Shah NP (2007) Functional cultures and health benefits. Int Dairy J 17(11):1262–1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.01.014

Wang C, Nagata S, Asahara T, Yuki N, Matsuda K, Tsuji H, Takahashi T, Nomoto K, Yamashiro Y (2015) Intestinal microbiota profiles of healthy pre-school and school-age children and effects of probiotic supplementation. Ann Nutr Metab 67(4):257–266. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441066

Black LI, Clarke TC, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ, Nahin RL (2015) Use of complementary health approaches among children aged 4–17 years in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2007–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep 78:1–19

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL (2015) Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. Natl Health Stat Rep 79:1–16

Wong S, Jamous A, O’Driscoll J, Sekhar R, Weldon M, Yau CY, Hirani SP, Grimble G, Forbes A (2014) A Lactobacillus casei Shirota probiotic drink reduces antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in patients with spinal cord injuries: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 111(4):672–678. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114513002973

Dietrich CG, Kottmann T, Alavi M (2014) Commercially available probiotic drinks containing Lactobacillus casei DN-114001 reduce antibiotic-associated diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol 20(42):15837–15844. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15837

Mazlyn MM, Nagarajah LH, Fatimah A, Norimah AK, Goh KL (2013) Effects of a probiotic fermented milk on functional constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 28(7):1141–1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12168

de Meij TG, Budding AE, de Groot EF, Jansen FM, Frank Kneepkens CM, Benninga MA, Penders J, van Bodegraven AA, Savelkoul PH (2016) Composition and stability of intestinal microbiota of healthy children within a Dutch population. FASEB J 30(4):1512–1522. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.15-278622

Budding AE, Grasman ME, Lin F, Bogaards JA, Soeltan-Kaersenhout DJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, van Bodegraven AA, Savelkoul PH (2010) IS-pro: high-throughput molecular fingerprinting of the intestinal microbiota. FASEB J 24(11):4556–4564. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.10-156190

Braga TD, da Silva GA, de Lira PI, de Carvalho Lima M (2011) Efficacy of Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus casei oral supplementation on necrotizing enterocolitis in very-low-birth-weight preterm infants: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 93(1):81–86. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29799

Buccigrossi V, Nicastro E, Guarino A (2013) Functions of intestinal microflora in children. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 29(1):31–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835a3500

Lin A, Bik EM, Costello EK, Dethlefsen L, Haque R, Relman DA, Singh U (2013) Distinct distal gut microbiome diversity and composition in healthy children from Bangladesh and the United States. PLoS ONE 8(1):e53838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053838

Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC, Clemente JC (2016) The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med 22:713. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4142

Hemarajata P, Versalovic J (2013) Effects of probiotics on gut microbiota: mechanisms of intestinal immunomodulation and neuromodulation. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 6(1):39–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283x12459294

Larsen OFA, Claassen E (2018) The mechanistic link between health and gut microbiota diversity. Sci Rep 8(1):2183. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20141-6

Ki Cha B, Mun Jung S, Hwan Choi C, Song ID, Woong Lee H, Joon Kim H, Hyuk J, Kyung Chang S, Kim K, Chung WS, Seo JG (2012) The effect of a multispecies probiotic mixture on the symptoms and fecal microbiota in diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 46(3):220–227. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823712b1

Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R (2012) Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489(7415):220–230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11550

Ashraf R, Shah NP (2014) Immune system stimulation by probiotic microorganisms. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 54(7):938–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2011.619671

Kang HJ, Im SH (2015) Probiotics as an immune modulator. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 61(Suppl):S103–S105. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.61.S103

Spanhaak S, Havenaar R, Schaafsma G (1998) The effect of consumption of milk fermented by Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the intestinal microflora and immune parameters in humans. Eur J Clin Nutr 52(12):899–907

Nagao F, Nakayama M, Muto T, Okumura K (2000) Effects of a fermented milk drink containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on the immune system in healthy human subjects. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 64(12):2706–2708

De Preter V, Vanhoutte T, Huys G, Swings J, De Vuyst L, Rutgeerts P, Verbeke K (2007) Effects of Lactobacillus casei Shirota, Bifidobacterium breve, and oligofructose-enriched inulin on colonic nitrogen-protein metabolism in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292(1):G358–G368. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00052.2006

Brocklehurst TF, Lund BM (1990) The influence of pH, temperature and organic acids on the initiation of growth of Yersinia enterocolitica. J Appl Bacteriol 69(3):390–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01529.x

Östling CE, Lindgren SE (1993) Inhibition of enterobacteria and Listeria growth by lactic, acetic and formic acids. J Appl Bacteriol 75(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03402.x

Eklund T (1983) The antimicrobial effect of dissociated and undissociated sorbic acid at different pH levels. J Appl Bacteriol 54(3):383–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1983.tb02632.x

Nagata S, Asahara T, Ohta T, Yamada T, Kondo S, Bian L, Wang C, Yamashiro Y, Nomoto K (2011) Effect of the continuous intake of probiotic-fermented milk containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on fever in a mass outbreak of norovirus gastroenteritis and the faecal microflora in a health service facility for the aged. Br J Nutr 106(4):549–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711451100064x

Matsumoto K, Takada T, Shimizu K, Moriyama K, Kawakami K, Hirano K, Kajimoto O, Nomoto K (2010) Effects of a probiotic fermented milk beverage containing Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on defecation frequency, intestinal microbiota, and the intestinal environment of healthy individuals with soft stools. J Biosci Bioeng 110(5):547–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.05.016

Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, van den Brandt PA, Stobberingh EE (2006) Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 118(2):511–521. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2824

Salminen S, Gibson GR, McCartney AL, Isolauri E (2004) Influence of mode of delivery on gut microbiota composition in seven year old children. Gut 53(9):1388–1389. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.041640

van den Bogert B, de Vos WM, Zoetendal EG, Kleerebezem M (2011) Microarray analysis and barcoded pyrosequencing provide consistent microbial profiles depending on the source of human intestinal samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 77(6):2071–2080. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02477-10

Couch RD, Navarro K, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet P, Forsyth CB, Mutlu E, Engen PA, Keshavarzian A (2013) The approach to sample acquisition and its impact on the derived human fecal microbiome and VOC metabolome. PLoS ONE 8(11):e81163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081163

Lepage P, Seksik P, Sutren M, de la Cochetiere MF, Jian R, Marteau P, Dore J (2005) Biodiversity of the mucosa-associated microbiota is stable along the distal digestive tract in healthy individuals and patients with IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis 11(5):473–480

Zoetendal EG, Raes J, van den Bogert B, Arumugam M, Booijink CC, Troost FJ, Bork P, Wels M, de Vos WM, Kleerebezem M (2012) The human small intestinal microbiota is driven by rapid uptake and conversion of simple carbohydrates. ISME J 6(7):1415–1426. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.212

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their contribution to this study. We would also like to thank B.I. Lissenberg-Witte for her excellent assistance in conducting the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that A.E.B. had proprietary rights on the IS-pro platform technology and is a cofounder of a spinoff company developing this technique. The fermented milk products were provided by Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd.; however, no financial contribution was made. In addition, Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd. had no role in the data collection, data interpretation, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

el Manouni el Hassani, S., de Boer, N.K.H., Jansen, F.M. et al. Effect of Daily Intake of Lactobacillus casei on Microbial Diversity and Dynamics in a Healthy Pediatric Population. Curr Microbiol 76, 1020–1027 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-019-01713-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-019-01713-9