Abstract

Purpose

Oral cannabinoids (i.e., dronabinol, nabilone) containing the active component of marijuana, delta(Δ)9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), are available for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with cancer who have failed to adequately respond to conventional antiemetic therapy. The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the efficacy, pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and safety of oral cannabinoids for patients with CINV.

Methods

A PubMed search of the English-language literature available through 4 January 2017 was conducted to identify relevant articles for inclusion in the review.

Results

Oral cannabinoids have been shown to have similar or improved efficacy compared with conventional antiemetics for the resolution of nausea and/or vomiting in patients with cancer. However, oral THC has high PK variability, with variability in oral dronabinol peak plasma concentrations (C max) estimated between 150 and 200%. A new oral dronabinol solution has decreased intraindividual variability (area under the curve) vs oral dronabinol capsules. Further, oral THC has a slower time to C max compared with THC administered intravenously (IV) or by smoking, and a lower systemic availability than IV or smoked THC. The PD profile (e.g., “high”) of oral THC differs from that of IV or smoked THC in healthy individuals. Oral cannabinoids are associated with greater incidence of adverse effects compared with conventional antiemetic therapy or placebo (e.g., dizziness, hypotension, and dysphoria or depression).

Conclusions

A new formulation of oral cannabinoids (i.e., dronabinol oral solution) minimized the PK/PD variability currently observed with capsule formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An estimated 45 to 61% of patients with cancer experience chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) [1, 2], which can occur as a result of chemotherapeutic agents and/or their metabolites activating neurotransmitter receptors in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [e.g., 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 (5-HT3)] and brain [e.g., neurokinin-1 (NK-1)] [3]. Acute CINV occurs within 24 h of initiating chemotherapy and mainly involves receptors in the GI tract, while delayed CINV occurs 1–5 days after starting chemotherapy and is primarily mediated by activation of receptors in the brain [3]. Delayed CINV occurs more frequently than acute CINV (58.4 vs 34.3%, respectively), and nausea is a more common component of the illness than vomiting (42 vs 20.8%) [1, 2, 4]. Oral and intravenous (IV) chemotherapeutic agents are classified in risk categories based on the frequency at which they may cause CINV in patients with cancer: high risk (>90%), moderate risk (30–90%), low risk (10–30%), and minimal risk (<10%) [5]. Patients receiving cancer chemotherapy categorized as moderate or high risk for nausea and vomiting typically remain at risk for ≥2 or ≥3 days, respectively, after receiving their final dose of chemotherapy [6]. Some agents are associated with a high emetogenic potential; emesis with cisplatin, for example, is generally most severe within 2–3 days of treatment, with symptoms present for 6–7 days, and potentially longer in some patients [5, 6].

The primary goal of antiemetic therapy is to prevent CINV [4, 7,8,9]. Patients with cancer receiving antiemetic therapy for the prevention of CINV according to guideline recommendations by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer [10] were significantly more likely to experience complete response to antiemetic treatment (i.e., no nausea or vomiting, no use of rescue therapy) compared with patients who did not receive antiemetic therapy as recommended (59.9 vs 50.7%, respectively; odds ratio [OR] 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.0–2.0; P = 0.03) [11]. A significantly greater percentage of patients with cancer receiving antiemetic therapy as recommended by guidelines had no CINV for 5 days after receiving a single dose of chemotherapy compared with patients receiving antiemetic treatment inconsistent with guidelines (53.4 vs 43.8%, respectively; P < 0.001) [12]. Thus, it is apparent that management of CINV according to published guidelines significantly improves this adverse effect of chemotherapy in patients.

In addition to the potential lack of adherence to antiemesis guidelines, additional barriers to optimal management of CINV include underestimation of the incidence of nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cancer treatment, as well as overestimation of the effectiveness of antiemetic treatment [1, 4, 13]. Fifty-four percent of patients with cancer receiving moderately emetic chemotherapy considered their antiemetic therapy to be effective (i.e., no nausea or vomiting, no rescue medication use) compared with a physician expectation of 75% [1]. Patient-related factors (e.g., age, race, income, education, alcohol use), cost of antiemetic therapy, and patient lack of adherence to antiemetic therapy may also negatively impact optimal management of CINV [14,15,16]. In some cases, patients fail to administer antiemetic therapy for prevention of CINV, instead choosing to wait for onset of nausea and vomiting [15].

Patients with poorly controlled CINV were more likely to experience a negative impact on daily function compared with patients with well-controlled CINV [2]. Additionally, results of an online survey of health care providers indicated that up to 32% of patients may experience a disruption of chemotherapy due to adverse events of nausea and vomiting [16]. Further, CINV has been associated with mean total direct costs (i.e., outpatient visits, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, medications) and indirect costs (i.e., work loss productivity, absenteeism) estimated at >$700 per patient during the 5 days following the first cycle of chemotherapy [2]. Thus, overcoming health care- and patient-related factors associated with poor control of CINV may impact outcomes in patients with cancer (e.g., improved quality of life, decreased costs).

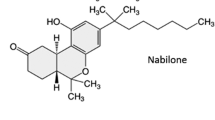

The main psychoactive component of marijuana (Cannabis sativa) is delta(Δ)9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which binds to cannabinoid receptors types 1 and 2 (CB1, CB2) that are located throughout the body, including in the brain (CB1) and the immune system (CB2) [17, 18]. Activation of CB1 by THC can have medically desirable effects, such as decreasing the incidence of nausea and vomiting [18]. Medical marijuana has been approved for use by approximately half of the states in the United States, although its use remains controversial [17]. However, synthetic pharmaceutical-grade THC (i.e., dronabinol capsules, nabilone capsules, and dronabinol oral solution) is approved in the United States for the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy in patients who failed to adequately respond to conventional antiemetic therapy [19,20,21]. Further, oral cannabinoids are recommended in guidelines for patients with cancer with breakthrough nausea and vomiting [8, 9]. Dronabinol is also indicated for the treatment of anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. The aim of this review article is to provide an overview of the efficacy, pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and safety of oral cannabinoids (i.e., dronabinol, nabilone) for the treatment of patients with cancer and CINV; the limited data available for the PK, PD, efficacy, and safety of medical marijuana are also presented in the context of CINV.

Materials and methods

A PubMed search of English-language articles available through 4 January 2017 was conducted to identify relevant articles for inclusion using the search terms “Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol”, “cannabinoid”, “dronabinol”, “nabilone”, “marijuana”, “cancer”, “chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting”, “pharmacokinetics”, “pharmacodynamics”, “efficacy”, and “safety”. Reference lists from identified articles were used to identify additional publications for inclusion. Guidelines for antiemesis in patients with cancer were identified either through PubMed and/or the website of the medical society involved in development of these guidelines [e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN; nccn.org)].

Results

Efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of oral cannabinoids

Efficacy of oral cannabinoids

The first placebo-controlled study demonstrating the efficacy of THC for the treatment of CINV in patients with cancer was published in 1975 [22]. Since publication of this initial report, numerous clinical studies have examined the antiemetic efficacy of oral dronabinol or nabilone capsules for the treatment of patients with CINV, with two meta-analyses reporting significant improvements with cannabinoids compared with conventional antiemetic therapy [23, 24], and one meta-analysis finding that, while the antiemetic efficacy of cannabinoids was favored, compared with the antiemetic prochlorperazine for the resolution of nausea, vomiting, or nausea and vomiting (Table 1), the findings did not achieve significance [25]. However, studies included in these meta-analyses differed in methodology (e.g., crossover study, blinding), discontinuation rates, sample sizes, timing of drug administration, tumor type, and chemotherapeutic agent(s) used [23,24,25]. Further, meta-analyses differed not only in the specific outcomes analyzed (e.g., antiemetic efficacy vs resolution of nausea or vomiting, or both), but also in the specific studies included in the evaluation of a particular efficacy outcome (i.e., number of studies) and whether cannabinoids were evaluated individually or by drug class [23,24,25].

In addition, a pooled analysis of 14 studies indicated that a significantly greater percentage of patients preferred cannabinoids compared with conventional antiemetics for the treatment of CINV [61 vs 26%, respectively; relative risk (RR) 2.4; 95% CI 2.1–2.8; number needed to treat, 2.8] [24]. These data were confirmed by a 2015 meta-analysis of nine studies that also reported patients preferred cannabinoids to conventional antiemetic agents (RR 2.8; 95% CI 1.9–4.0) [25]. Reasons for these similar findings were not provided, but the results may be antiemetic-dependent, as there were no differences between patient preference for cannabinoids over metoclopramide or chlorpromazine in single studies with a small number of participants (N = 40 and N = 64, respectively) [25].

Medical use of marijuana is controversial and no clinical trials have been conducted to date to compare the antiemetic efficacy of medical marijuana with the conventional antiemetic agents recommended as first-line therapy by the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Antiemesis [17, 26]. Medical marijuana is currently not recommended by the NCCN for antiemesis in CINV [26]. However, given that approximately half of all states in the United States have approved the use of medical marijuana, health care providers are increasingly likely to encounter patients interested in receiving medical marijuana for antiemesis [17].

Variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids

Lack of antiemetic efficacy (i.e., failure to decrease incidence of CINV) of oral THC was initially reported in patients with sarcoma receiving chemotherapy. In these patients, the lack of antiemetic efficacy was thought to possibly be associated with the type of chemotherapeutic agent administered [27]. However, absorption of THC was also highly variable, with decreased incidence of nausea and vomiting associated with higher drug plasma concentrations of THC (50% incidence at >5 ng/mL vs 83% at <5 ng/mL). Subsequent studies of orally administered THC have confirmed high PK variability in healthy individuals (Table 2) [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Oral absorption of dronabinol is high (90–95%), but slow and variable [34]. Peak plasma concentrations of dronabinol and its metabolites have been observed at ~2 h postdose with dronabinol capsule in healthy individuals [31, 32]. Variability in peak plasma concentrations (C max) was estimated between 150 and 200% [28]. In healthy individuals currently reporting cannabis use, administration of supratherapeutic doses of THC (i.e., 75–90 mg) were associated with high interindividual variability [C max range 9.0–127.1 ng/mL; time to C max (T max) range 1–12 h] [33].

A new tablet formulation of THC designed to improve drug uptake demonstrated a more rapid T max in healthy individuals, with interindividual variability in C max ranging from 42 to 62% [28]. In one study, peak plasma levels of oral THC (e.g., tablet, capsule) were lower and were achieved over a longer duration compared with IV THC, which reached peak plasma concentrations within 20 min of administration (C max, 62 ng/mL) [32]. In this study, participants reported a maximal “high” feeling, a subjective psychological effect of THC use, 30–50 min after IV administration, compared with 2.5–3 h after oral THC administration. By further comparison, participants who smoked marijuana reported a maximal “high” feeling at 30–90 min postdose, long after C max was achieved. These physiologic effects may be mediated by the major metabolites of THC, including 11-hydroxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (11-OH-THC) and 11-nor-9-carboxy-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC-COOH) [32, 35], which were shown to have a longer T max than THC when marijuana was smoked (i.e., T max for a marijuana cigarette containing 3.55% THC: THC, 0.14 h; 11-OH-THC, 0.2 h; THC-COOH, 1.35 h) [36]. Systemic availability of oral THC is lower than that of smoked THC (4–12% vs 8–24%, respectively) [34, 37], as the systemic availability of oral THC is limited by extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism [35].

With regard to medical marijuana, dosing of smoked marijuana is variable, given interindividual differences in frequency and depth of inhalations, and the type of cannabis selected, as cannabinoid content varies by blend [28, 29]. High interindividual PK variability was demonstrated in a study of healthy individuals smoking low- and high-dose cannabis (i.e., containing 1.75 and 3.55% THC, respectively) [36]. The smoking protocol of this study included a 2-s inhalation, 10-s hold period, and 72-s exhalation and rest period for a total of 8 puffs over 11.2 min. Peak plasma concentrations of THC were observed 8.4 min after the first puff, with a mean C max of 84.3 ng/mL (range 50–129 ng/mL) for low-dose cannabis and 162.2 ng/mL (range 76–267 ng/mL) for high-dose cannabis; THC plasma concentrations then decreased rapidly to 17.3 and 29.7 ng/mL, respectively, after 30 min.

Inhaling vaporized THC reduced exposure to harmful byproducts produced by smoking cannabis [26, 38]. Peak plasma concentrations of THC after inhalation of low- or high-dose vaporized cannabis (2.9% THC, 46.5 µg/L; 6.7% THC, 62.1 µg/L) were achieved within 10 min of administration in healthy regular users of cannabis [38]. Interindividual PK variability was observed with inhalation of vaporized THC, which was attributed, in part, to rate and depth of inhalation and time THC was held in the lungs of participants, as well as factors associated with delivery of vaporized THC, including heating temperature, number of balloon fills, and the amount and type of cannabis used [38].

The PD of oral THC is variable and differs from that of smoked or IV THC (Fig. 1) [30, 37, 39]. The PK/PD profile of orally administered THC (i.e., cookie) was shown to differ from that of smoked and IV administration of the drug in individuals with prior cannabis exposure [39]. Maximal feeling of “high” was achieved 30 min after smoking or IV administration of THC, and declined to baseline levels after 4 h; in contrast, after oral administration of THC, maximal feeling of “high” was slower in onset (i.e., 2–4 h), with a decline to baseline levels after 6 h. Peak plasma concentrations were achieved within 3 min following smoking or IV administration, but within approximately 1 h with oral administration. Plasma THC concentrations and the degree of “high” experienced by participants had high intra- and interindividual variability. Further, clinical signs of cannabis intoxication (e.g., reddening of conjunctivae, increased pulse rate) differed between smoked and IV administration vs oral administration [37]. Reddening of the conjunctivae reached a maximum effect by 10 min following smoking and IV administration, compared with a maximal effect observed 1–3 h after oral administration. In general, reddening of conjunctivae occurred with plasma THC concentrations >5 ng/mL, even in the absence of feeling “high.” The median increase from baseline in pulse rate was comparable between smoking and IV administration: an increase of 34 beats per minute (bpm) was observed with a median THC concentration of 45 ng/mL obtained via smoking, vs 40 bpm with a median plasma concentration of 100 ng/mL via IV administration. The effect of oral administration on pulse rate was lower compared with smoking and IV administration (26 bpm with a median THC concentration of 4.5 ng/mL). Pulse rate often returned to baseline or below while plasma concentrations remained >5 ng/mL and patients still reported feeling “high” [37]. Thus, it is apparent that plasma THC concentrations >5 ng/mL correlate better with reddening of conjunctivae than pulse rate, although both are considered clinical indicators of cannabis intoxication.

Single-dose oral administration of THC tablets (3.0, 5.0, or 6.5 mg) in healthy adults ≥65 years of age indicated no association between plasma THC concentrations and eyes open-body sway scores [P = 0.1; determined by SwayStar™ (BESTec-etp Freiburg GmbH, Freiburg, Germany), a device used to measure body movement when standing with eyes open or closed]. However, the eyes open-body sway scores were associated with plasma concentrations of the THC metabolites 11-OH-THC and THC-COOH [30]. This is a potentially clinically relevant finding in the context of falls, which are a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly [40]. In the same study of THC tablets, alertness scores were not associated with plasma concentrations of THC (P = 0.5), or its metabolites 11-OH-THC (P = 0.7) and THC-COOH (P = 0.8) [30].

The high PK variability of oral THC tablets and capsules may compromise accurate and consistent dosing of dronabinol [28]. The oral dronabinol solution formulation, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2016, has been shown to have less variability, with drug detected in plasma in 15 min in 100% of individuals receiving this formulation compared with <25% of individuals receiving dronabinol capsule (Fig. 2) [41]. Further, the intraindividual variability in the mean area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity (AUC0–∞) was decreased with oral dronabinol solution compared with the capsule. These findings have important clinical implications for patients with CINV, as patients may derive therapeutic benefit faster with oral dronabinol solution than with dronabinol capsule. Further, decreased intraindividual variability with oral dronabinol solution vs capsule may minimize the need to individualize dosing to obtain optimal therapeutic effects [19]. However, if needed, individualized dosing based on body surface area and titration of dosing to achieve clinical benefit is supported by current US labeling [21].

Variability in pharmacokinetics of oral dronabinol capsule 5 mg and oral dronabinol solution 4.25 mg following single-dose administration in healthy individuals [41]. aData for 2 replicates. AUC 0–∞ area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity, C max maximum plasma concentration, SD standard deviation

Safety of cannabinoids

Cannabinoids are associated with a number of potential adverse effects, including a “high” feeling, euphoria, disorientation, and depression [26]. Adverse effects of cannabinoids on non–central nervous system functions (e.g., tachycardia, reddening of conjunctivae, decreased GI motility) are attributed to the ubiquitous localization of cannabinoid receptors throughout the body [42]. Results of a meta-analysis showed that patients receiving oral dronabinol or nabilone capsules had greater incidence of adverse effects compared with those receiving conventional antiemetic therapy or placebo: dizziness, 49 vs 17%, respectively; hypotension, 25 vs 11%; dysphoria or depression, 13 vs 0.3%; hallucinations, 6 vs 0%; and paranoia, 5 vs 0% [24]. Medical use of cannabinoids (including oral dronabinol and nabilone capsules) for various conditions, including CINV, chronic pain, spasticity related to multiple sclerosis or paraplegia, human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS, and sleep disorder, was associated with a greater risk of adverse effects compared with an active comparator or placebo in 62 studies [43]. Overall, the most common adverse effects following administration of cannabinoids included disorientation (OR 5.4; 95% CI 2.6–11.2), dizziness (OR 5.1; 95% CI 4.1–6.3), euphoria (OR 4.1; 95% CI 2.2–7.6), confusion (OR 4.0; 95% CI 2.1–8.0), and drowsiness (OR 3.7; 95% CI 2.2–6.0). Although data are limited, single-dose dronabinol oral solution was shown to be generally well tolerated, with nausea, dizziness, somnolence, and headache the most common adverse events reported by healthy volunteers [41].

Considerations for oral cannabinoids compared with medical marijuana

Numerous routes of administration are available for patients with cancer receiving medical marijuana, including smoking, oral (e.g., cookie, candy, beverages), and mucosal [44,45,46]. In contrast with oral cannabinoids (i.e., dronabinol, nabilone), medical marijuana is not currently regulated by the FDA [47]. Thus, there is currently a lack of standardization regarding dosing and potency across available medical marijuana formulations; additionally, the potential for food safety issues cannot be excluded for users of oral products (i.e., foodstuffs, beverages) [44,45,46, 48]. While edible medical marijuana products are required to have child-resistant packaging and labeling, unintentional pediatric exposures may still occur [47, 49]. Use of smoked marijuana for medical purposes by patients with cancer has several limitations, including a patient’s inability to tolerate smoked marijuana due to taste or the potential for airway obstruction, which may result from inflammation of the airway following smoking [50, 51]. Medical marijuana may also increase the risk for atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarct, and chronic bronchitis [26]. Further, patients who are immunocompromised may risk additional immunosuppression (e.g., by suppressing lymphocyte proliferation) following use of medical marijuana [26, 52]. In addition, insurance will generally cover the costs associated with use of cannabinoids approved by the FDA, but not medical marijuana. Overall, additional studies comparing the safety and efficacy of oral cannabinoids with various formulations of medical marijuana are needed.

Discussion

Management of patients receiving cancer chemotherapy includes preventing the treatment-related adverse effects of nausea and vomiting [9]. Most clinical studies of antiemetic agents in patients affected by CINV have focused on prevention, rather than treatment, of nausea and vomiting, supporting earlier intervention rather than delayed use [53]. However, given that many patients are at risk for CINV for days after receiving the last dose of chemotherapy [6], identification of effective therapies for the treatment of current CINV symptoms is important. A number of factors play a role when considering therapeutic options for controlling CINV, including tolerability of antiemetic therapy, patient setting (i.e., inpatient, outpatient), and patient preference [e.g., route of administration (oral, IV)] [9]. Oral cannabinoids were initially approved for the treatment of CINV in the 1980s; however, current use of this drug class for the treatment of CINV is limited by occurrence of adverse effects, including dizziness, dry mouth, and drowsiness, in some patients [43, 53]. Further, oral cannabinoids were, until recently, only available as capsules or tablets. The recent approval of medical marijuana in a number of states warrants additional well-designed studies examining efficacy and safety in patients with CINV.

The recently approved oral dronabinol solution not only has a favorable PK profile, but plasma levels of dronabinol were detected within 15 min in all individuals examined [21, 41]. Patients with CINV may benefit from these favorable attributes of oral dronabinol solution, with the potential for faster onset of relief of nausea and vomiting. Further, oral dronabinol solution is an easy-to-swallow formulation for patients with CINV that is administered using a 1-mL oral syringe provided with the medication; of note, labeling indicates that oral dronabinol solution should be administered with 6–8 oz of water [21]. Finally, while use of oral cannabinoids is limited by the potential for adverse effects, patients with CINV refractory to treatment with other antiemetic agents may benefit from administration of dronabinol or nabilone for treatment of CINV [25].

Some practical considerations should be noted for oral dronabinol solution, including that the agent is available as an unflavored 5 mg/mL formulation with a clear, pale yellow to brown color [21]. Dosing should be calculated based on patient body surface area (m2) multiplied by 4.2 mg/m2 and rounded to 0.1 mg [21]. Patients should receive an initial dose of dronabinol oral solution on an empty stomach (i.e., 30 min before eating) 1–3 h prior to receiving chemotherapy; subsequent doses can be administered, without considering timing of food consumption, every 2–4 h after chemotherapy (up to 4–6 doses daily) [21]. Dronabinol oral solution is contraindicated in patients receiving disulfiram- or metronidazole-containing agents currently, or within the past 14 days, as patients may experience a disulfiram-like reaction (e.g., abdominal cramping, nausea, vomiting) [21]. Patients with a history of seizures should be monitored, given that seizures and seizure-like activity have been reported with dronabinol [21]. Patients may experience new or worsening nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, the occurrence of which requires a decrease in dosing or discontinuation of dronabinol oral solution [21]. In addition, dronabinol oral solution should not be administered to patients with a history of psychiatric events [21].

Conclusions

Oral cannabinoids (i.e., tablets, capsules) are efficacious for the management of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy treatment, but capsules are associated with an increased incidence of adverse effects compared with conventional antiemetic therapy [24, 26, 43]. However, patients have shown a preference for oral cannabinoid therapy (i.e., tablets, capsules) compared with some conventional antiemetics [24, 25]. The PK/PD profile of oral cannabinoids administered as capsules is highly variable and differs from that of THC smoked or administered by IV [30, 32, 37, 39]. Medical marijuana (i.e., smoked, vaporized, ingested) also has a variable PK profile, for reasons thought to be associated with individual differences in inhalation and/or type of cannabis being used [28, 29, 39]. The 2016 approval of dronabinol oral solution may reduce the PK variability currently observed with oral dronabinol capsule formulations and may provide patients with CINV the option of greater treatment flexibility. However, more studies examining the PK profile of THC-containing products in patients with CINV are warranted, as data for this specific population are currently lacking in the literature.

References

Escobar Y, Cajaraville G, Virizuela JA, Alvarez R, Munoz A, Olariaga O, Tames MJ, Muros B, Lecumberri MJ, Feliu J, Martinez P, Adansa JC, Martinez MJ, Lopez R, Blasco A, Gascon P, Calvo V, Luna P, Montalar J, Del BP, Tornamira MV (2015) Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: ADVICE (Actual Data of Vomiting Incidence by Chemotherapy Evaluation) study. Support Care Cancer 23(9):2833–2840

Haiderali A, Menditto L, Good M, Teitelbaum A, Wegner J (2011) Impact on daily functioning and indirect/direct costs associated with chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in a U.S. population. Support Care Cancer 19(6):843–851

Navari RM, Aapro M (2016) Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 374(14):1356–1367

Jordan K, Gralla R, Jahn F, Molassiotis A (2014) International antiemetic guidelines on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): content and implementation in daily routine practice. Eur J Pharmacol 722:197–202

Grunberg SM, Warr D, Gralla RJ, Rapoport BL, Hesketh PJ, Jordan K, Espersen BT (2011) Evaluation of new antiemetic agents and definition of antineoplastic agent emetogenicity–state of the art. Support Care Cancer 19(Suppl 1):S43–S47

Ettinger DS, Armstrong DK, Barbour S, Berger MJ, Bierman PJ, Bradbury B, Ellis G, Kirkegaard S, Kloth DD, Kris MG, Lim D, Michaud LB, Nabati L, Noonan K, Rugo HS, Siler D, Sorscher SM, Stelts S, Stucky-Marshall L, Todaro B, Urba SG (2012) Antiemesis. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 10(4):456–485

Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Feyer PC, Somerfield MR, Chesney M, Clark-Snow RA, Flaherty AM, Freundlich B, Morrow G, Rao KV, Schwartz RN, Lyman GH (2011) Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 29(31):4189–4198

Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, Gralla RJ, Einhorn LH, Ballatori E, Bria E, Clark-Snow RA, Espersen BT, Feyer P, Grunberg SM, Hesketh PJ, Jordan K, Kris MG, Maranzano E, Molassiotis A, Morrow G, Olver I, Rapoport BL, Rittenberg C, Saito M, Tonato M, Warr D (2010) Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol 21(Suppl 5):v232–v243

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Antiemesis. (2016). Accessed 5 May 2016

Roila F, Hesketh PJ, Herrstedt J (2006) Prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced emesis: results of the 2004 Perugia International Antiemetic Consensus Conference. Ann Oncol 17(1):20–28

Aapro M, Molassiotis A, Dicato M, Pelaez I, Rodriguez-Lescure A, Pastorelli D, Ma L, Burke T, Gu A, Gascon P, Roila F (2012) The effect of guideline-consistent antiemetic therapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): the Pan European Emesis Registry (PEER). Ann Oncol 23(8):1986–1992

Gilmore JW, Peacock NW, Gu A, Szabo S, Rammage M, Sharpe J, Haislip ST, Perry T, Boozan TL, Meador K, Cao X, Burke TA (2014) Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE Study. J Oncol Pract 10(1):68–74

Basch E (2010) The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med 362(10):865–869

Gomez DR, Liao KP, Giordano S, Nguyen H, Smith BD, Elting LS (2013) Adherence to national guidelines for antiemesis prophylaxis in patients undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancer: a population-based study. Cancer 119(7):1428–1436

Chan A, Low XH, Yap KY (2012) Assessment of the relationship between adherence with antiemetic drug therapy and control of nausea and vomiting in breast cancer patients receiving anthracycline-based chemotherapy. J Manag Care Pharm 18(5):385–394

Van Laar ES, Desai JM, Jatoi A (2015) Professional educational needs for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): multinational survey results from 2388 health care providers. Support Care Cancer 23(1):151–157

Wilkie G, Sakr B, Rizack T (2016) Medical marijuana use in oncology: a review. JAMA Oncol 2(5):670–675

Pacher P, Kunos G (2013) Modulating the endocannabinoid system in human health and disease-successes and failures. FEBS J 280(9):1918–1943

Marinol® (dronabinol) capsules [package insert] (2017) AbbVie Inc., North Chicago

Cesamet® (nabilone) capsules for oral administration [package insert] (2013) Meda Pharmaceuticals, Somerset

SYNDROSTM (dronabinol) oral solution, CX [package insert] (2016) Insys Therapeutics, Inc., Chandler

Sallan SE, Zinberg NE, Frei EI (1975) Antiemetic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 293(16):795–797

Machado Rocha F, Stéfano S, De Cássia HR, Rosa Oliveira LM, Da Silveira D (2008) Therapeutic use of cannabis sativa on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting among cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 17(5):431–443

Tramer MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (2001) Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ 323(7303):16–21

Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, Stoner NS, Bettiol S (2015) Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD009464

Todaro B (2012) Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 10(4):487–492

Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, Goldberg NH, Seipp CA, Barofsky I, Rosenberg SA (1981) A prospective evaluation of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in patients receiving adriamycin and cytoxan chemotherapy. Cancer 47(7):1746–1751

Klumpers LE, Beumer TL, van Hasselt JG, Lipplaa A, Karger LB, Kleinloog HD, Freijer JI, de Kam ML, van Gerven JM (2012) Novel ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol formulation Namisol® has beneficial pharmacokinetics and promising pharmacodynamic effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 74(1):42–53

Nadulski T, Sporkert F, Schnelle M, Stadelmann AM, Roser P, Schefter T, Pragst F (2005) Simultaneous and sensitive analysis of THC, 11-OH-THC, THC-COOH, CBD, and CBN by GC-MS in plasma after oral application of small doses of THC and cannabis extract. J Anal Toxicol 29(8):782–789

Ahmed AI, van den Elsen GA, Colbers A, van der Marck MA, Burger DM, Feuth TB, Rikkert MG, Kramers C (2014) Safety and pharmacokinetics of oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy older subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 24(9):1475–1482

Naef M, Curatolo M, Petersen-Felix S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Zbinden A, Brenneisen R (2003) The analgesic effect of oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), morphine, and a THC-morphine combination in healthy subjects under experimental pain conditions. Pain 105(1–2):79–88

Wall ME, Perez-Reyes M (1981) The metabolism of ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol and related cannabinoids in man. J Clin Pharmacol 21(8–9 Suppl):178S–189S

Lile JA, Kelly TH, Charnigo RJ, Stinchcomb AL, Hays LR (2013) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of supratherapeutic oral doses of ∆9-THC in cannabis users. J Clin Pharmacol 53(7):680–690

McGilveray IJ (2005) Pharmacokinetics of cannabinoids. Pain Res Manag 10(Suppl A):15A–22A

Grotenhermen F (2003) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 42(4):327–360

Huestis MA, Henningfield JE, Cone EJ (1992) Blood cannabinoids. I. Absorption of THC and formation of 11-OH-THC and THCCOOH during and after smoking marijuana. J Anal Toxicol 16(5):276–282

Ohlsson A, Lindgren JE, Wahlen A, Agurell S, Hollister LE, Gillespie HK (1980) Plasma delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol concentrations and clinical effects after oral and intravenous administration and smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther 28(3):409–416

Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz G, Spurgin A, Gorelick DA, Gaffney G, Huestis MA (2015) Controlled cannabis vaporizer administration: blood and plasma cannabinoids with and without alcohol. Clin Chem 61(6):850–869

Hollister LE, Gillespie HK, Ohlsson A, Lindgren JE, Wahlen A, Agurell S (1981) Do plasma concentrations of ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol reflect the degree of intoxication? J Clin Pharmacol 21(8–9 Suppl):171S–177S

Cesari M, Landi F, Torre S, Onder G, Lattanzio F, Bernabei R (2002) Prevalence and risk factors for falls in an older community-dwelling population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 57(11):M722–M726

Parikh N, Kramer WG, Khurana V, Cognata Smith C, Vetticaden S (2016) Bioavailability study of dronabinol oral solution versus dronabinol capsules in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol 8:155–162

Abrams DI, Guzman M (2015) Cannabis in cancer care. Clin Pharmacol Ther 97(6):575–586

Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di NM, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, Keurentjes JC, Lang S, Misso K, Ryder S, Schmidlkofer S, Westwood M, Kleijnen J (2015) Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 313(24):2456–2473

Ghosh TS, Van Dyke M, Maffey A, Whitley E, Erpelding D, Wolk L (2015) Medical marijuana’s public health lessons—implications for retail marijuana in Colorado. N Engl J Med 372(11):991–993

Moeller KE, Woods B (2015) Pharmacy students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding medical marijuana. Am J Pharm Educ 79(6):85

Birdsall SM, Birdsall TC, Tims LA (2016) The use of medical marijuana in cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 18(7):40

MacCoun RJ, Mello MM (2015) Half-baked–the retail promotion of marijuana edibles. N Engl J Med 372(11):989–991

Nelson B (2015) Medical marijuana: hints of headway? Despite a conflicted regulatory landscape, support for medical marijuana is growing amid increasing evidence of potential benefits. Cancer Cytopathol 123(2):67–68

Monte AA, Zane RD, Heard KJ (2015) The implications of marijuana legalization in Colorado. JAMA 313(3):241–242

Poster DS, Penta JS, Bruno S, Macdonald JS (1981) ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol in clinical oncology. JAMA 245(20):2047–2051

Zhang MW, Ho RC (2015) The cannabis dilemma: a review of its associated risks and clinical efficacy. J Addict 2015:707596

Joy J, Watson S, Benson JJ (eds) (1999) Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C

Slatkin NE (2007) Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: beyond prevention of acute emesis. J Support Oncol 5(5 Suppl 3):1–9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

M.E.B. reports no conflicts of interest. Technical editorial and medical writing assistance was provided under the direction of M.E.B. by Mary Beth Moncrief, PhD, and Sophie Bolick, PhD, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA. Funding for this support was provided by Insys Development Company, Chandler, AZ.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Badowski, M.E. A review of oral cannabinoids and medical marijuana for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a focus on pharmacokinetic variability and pharmacodynamics. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 80, 441–449 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-017-3387-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-017-3387-5