Abstract

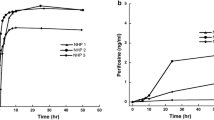

Clofarabine, a deoxyadenosine analog, was an active anticancer drug in our in vitro high-throughput screening against mouse ependymoma neurospheres. To characterize the clofarabine disposition in mice for further preclinical efficacy studies, we evaluated the plasma and central nervous system disposition in a mouse model of ependymoma. A plasma pharmacokinetic study of clofarabine (45 mg/kg, IP) was performed in CD1 nude mice bearing ependymoma to obtain initial plasma pharmacokinetic parameters. These estimates were used to derive D-optimal plasma sampling time points for cerebral microdialysis studies. A simulation of clofarabine pharmacokinetics in mice and pediatric patients suggested that a dosage of 30 mg/kg IP in mice would give exposures comparable to that in children at a dosage of 148 mg/m2. Cerebral microdialysis was performed to study the tumor extracellular fluid (ECF) disposition of clofarabine (30 mg/kg, IP) in the ependymoma cortical allografts. Plasma and tumor ECF concentration–time data were analyzed using a nonlinear mixed effects modeling approach. The median unbound fraction of clofarabine in mouse plasma was 0.79. The unbound tumor to plasma partition coefficient (K pt,uu: ratio of tumor to plasma AUCu,0–inf) of clofarabine was 0.12 ± 0.05. The model-predicted mean tumor ECF clofarabine concentrations were below the in vitro 1-h IC50 (407 ng/mL) for ependymoma neurospheres. Thus, our results show the clofarabine exposure reached in the tumor ECF was below that associated with an antitumor effect in our in vitro washout study. Therefore, clofarabine was de-prioritized as an agent to treat ependymoma, and further preclinical studies were not pursued.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ostrom QT et al (2014) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol 16(Suppl 4):iv1–iv63

Ridley L et al (2008) Multifactorial analysis of predictors of outcome in pediatric intracranial ependymoma. Neuro Oncol 10(5):675–689

Atkinson JM et al (2011) An integrated in vitro and in vivo high-throughput screen identifies treatment leads for ependymoma. Cancer Cell 20(3):384–399

Bonate PL et al (2006) Discovery and development of clofarabine: a nucleoside analogue for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5(10):855–863

Zhenchuk A et al (2009) Mechanisms of anti-cancer action and pharmacology of clofarabine. Biochem Pharmacol 78(11):1351–1359

Parker WB et al (1991) Effects of 2-chloro-9-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-beta-D-arabinofuranosyl)adenine on K562 cellular metabolism and the inhibition of human ribonucleotide reductase and DNA polymerases by its 5′-triphosphate. Cancer Res 51(9):2386–2394

Genini D et al (2000) Deoxyadenosine analogs induce programmed cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by damaging the DNA and by directly affecting the mitochondria. Blood 96(10):3537–3543

Bonate PL et al (2011) Population pharmacokinetics of clofarabine and its metabolite 6-ketoclofarabine in adult and pediatric patients with cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67(4):875–890

Jeha S et al (2004) Clofarabine, a novel nucleoside analog, is active in pediatric patients with advanced leukemia. Blood 103(3):784–789

Jeha S et al (2009) Phase II study of clofarabine in pediatric patients with refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 27(26):4392–4397

Kantarjian HM et al (2003) Phase I clinical and pharmacology study of clofarabine in patients with solid and hematologic cancers. J Clin Oncol 21(6):1167–1173

Berg SL et al (2005) Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of clofarabine in non-human primates. Clin Cancer Res 11(16):5981–5983

Johnson RA et al (2010) Cross-species genomics matches driver mutations and cell compartments to model ependymoma. Nature 466(7306):632–636

Leggas M et al (2004) Microbore HPLC method with online microdialysis for measurement of topotecan lactone and carboxylate in murine CSF. J Pharm Sci 93(9):2284–2295

Morfouace M et al (2014) Pemetrexed and gemcitabine as combination therapy for the treatment of Group3 medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell 25(4):516–529

Kariv I, Cao H, Oldenburg KR (2001) Development of a high throughput equilibrium dialysis method. J Pharm Sci 90(5):580–587

CDC (2013) Weight-for-age charts, 2–20 years, LMS parameters and selected smoothed weight percentiles in kilograms by sex and age. CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), Atlanta

Bonate PL et al (2004) Population pharmacokinetics of clofarabine, a second-generation nucleoside analog, in pediatric patients with acute leukemia. J Clin Pharmacol 44(11):1309–1322

Ette EI (1996) Comparing non-hierarchical models: application to non-linear mixed effects modeling. Comput Biol Med 26(6):505–512

Bonate PL et al (2005) The distribution, metabolism, and elimination of clofarabine in rats. Drug Metab Dispos 33(6):739–748

Carcaboso AM et al (2010) Tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib enhances topotecan penetration of gliomas. Cancer Res 70(11):4499–4508

Bauer R (2011) NONMEM users guide: Introduction to NONMEM 7.2.0. I.D. Solutions Editor, Ellicott City

D’Argenio DZ, Schumitzky A, Wang X (2009) ADAPT 5 user’s guide: pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Biomedical Simulations Resource, Los Angeles

D’Argenio DZ (1981) Optimal sampling times for pharmacokinetic experiments. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 9(6):739–756

Hofstein R, Hesse G, Shashoua VE (1983) Proteins of the extracellular fluid of mouse brain: extraction and partial characterization. J Neurochem 40(5):1448–1455

Jacus MO et al (2014) Deriving therapies for children with primary CNS tumors using pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation of cerebral microdialysis data. Eur J Pharm Sci 57:41–47

Di L, Rong H, Feng B (2013) Demystifying brain penetration in central nervous system drug discovery. Miniperspective. J Med Chem 56(1):2–12

Pardridge WM (2001) Crossing the blood–brain barrier: are we getting it right? Drug Discov Today 6(1):1–2

Advani AS et al (2014) SWOG S0910: a phase 2 trial of clofarabine/cytarabine/epratuzumab for relapsed/refractory acute lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 165(4):504–509

Cooper TM et al (2014) AAML0523: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group on the efficacy of clofarabine in combination with cytarabine in pediatric patients with recurrent acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 120:2482–2489

Cooper TM et al (2013) Phase I/II trial of clofarabine and cytarabine in children with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (AAML0523): a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60(7):1141–1147

Willemze R et al (2014) Clofarabine in combination with a standard remission induction regimen (cytosine arabinoside and idarubicin) in patients with previously untreated intermediate and bad-risk acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (HR-MDS): phase I results of an ongoing phase I/II study of the leukemia groups of EORTC and GIMEMA (EORTC GIMEMA 06061/AML-14A trial). Ann Hematol 93(6):965–975

Cunningham CC et al (2005) Clofarabine administration weekly to adult patients with advanced solid tumors in a phase I dose-finding study. ASCO Annu Meet Proc 23(16S):7109

King KM et al (2006) A comparison of the transportability, and its role in cytotoxicity, of clofarabine, cladribine, and fludarabine by recombinant human nucleoside transporters produced in three model expression systems. Mol Pharmacol 69(1):346–353

Begley CG, Ellis LM (2012) Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 483(7391):531–533

Morgan P et al (2012) Can the flow of medicines be improved? Fundamental pharmacokinetic and pharmacological principles toward improving Phase II survival. Drug Discov Today 17(9–10):419–424

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the staff of the Animal Resource Center (ARC) and Small Animal Imaging Center (SAIC) at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital for their technical assistance. Supported in part by Cancer Center Support CORE Grant P30 CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute, the Collaborative Ependymoma Research Network (CERN), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, Y.T., Jacus, M.O., Boulos, N. et al. Preclinical examination of clofarabine in pediatric ependymoma: intratumoral concentrations insufficient to warrant further study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 75, 897–906 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2713-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2713-z