Abstract

Background

A positive relationship between an individual surgeon’s operative volume and clinical outcomes after pediatric and adult thyroidectomy is well-established. The impact of a hospital’s pediatric operative volume on surgical outcomes and healthcare utilization, however, are infrequently reported. We investigated associations between hospital volume and healthcare utilization outcomes following pediatric thyroidectomy in Canada’s largest province, Ontario.

Methods

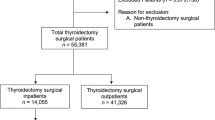

Retrospective analysis of administrative and health-related population-level data from 1993 to 2017. A cohort of 1908 pediatric (<18 years) index thyroidectomies was established. Hospital volume was defined per-case as thyroidectomies performed in the preceding year. Healthcare utilization outcomes: length of stay (LOS), same day surgery (SDS), readmission, and emergency department (ED) visits were measured. Multivariate analysis adjusted for patient-level, disease and hospital-level co-variates.

Results

Hospitals with the lowest volume of pediatric thyroidectomies, accounted for 30% of thyroidectomies province-wide and performed 0–1 thyroidectomies/year. The highest-volume hospitals performed 19–60 cases/year. LOS was 0.64 days longer in the highest, versus the lowest quartile. SDS was 83% less likely at the highest, versus the lowest quartile. Hospital volume was not associated with rate of readmission or ED visits. Increased ED visits were, however, associated with male sex, increased material deprivation, and rurality.

Conclusions

Increased hospital pediatric surgical volume was associated with increased LOS and lower likelihood of SDS. This may reflect patient complexity at such centers. In this cohort, low-volume hospitals were not associated with poorer healthcare utilization outcomes. Further study of groups disproportionately accessing the ED post-operatively may help direct resources to these populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sosa JA, Tuggle CT, Wang TS et al (2008) Clinical and economic outcomes of thyroid and parathyroid surgery in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93(8):3058–3065

Adam MA, Thomas S, Youngwirth L et al (2017) Is there a minimum number of thyroidectomies a surgeon should perform to optimize patient outcomes? Ann Surg 265(2):402–407

Hauch A, Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph G et al (2014) Total thyroidectomy is associated with increased risk of complications for low- and high-volume surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol 21(12):3844–3852

Krishnamurthy VD, Jin J, Siperstein A et al (2016) Mapping endocrine surgery: workforce analysis from the last six decades. Surgery 159(1):102–112

Sosa JA, Bowman H, Tielsch J, Powe NR et al (1998) The importance of surgeon experience for clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg 228(3):320–330

Stavrakis AI, Ituarte PHG, Ko CY et al (2007) Surgeon volume as a predictor of outcomes in inpatient and outpatient endocrine surgery. Surgery 142(6):887–899

Al-Qurayshi Z, Randolph GW, Srivastav S (2015) Outcomes in endocrine cancer surgery are affected by racial, economic, and healthcare system demographics. Laryngoscope 126(3):775–781

Al-Qurayshi Z, Hauch A, Srivastav S et al (2016) A national perspective of the risk, presentation, and outcomes of pediatric thyroid cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(5):472–477

Drews JD, Cooper JN, Onwuka EA (2019) The relationships of surgeon volume and specialty with outcomes following pediatric thyroidectomy. J Pediatr Surg 54(6):1226–1232

Meltzer C, Hull M, Sundang A et al (2019) Association between annual surgeon total thyroidectomy volume and transient and permanent complications. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 145(9):830–838

Breuer C, Tuggle C, Solomon D et al (2013) Pediatric thyroid disease: when is surgery necessary, and who should be operating on our children? J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 5(Suppl 1):79–85

Francis GL, Waguespack SG, Bauer AJ et al (2015) Management guidelines for children with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 25(7):716–759

Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV et al (2002) Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 346(15):1128–1137

McAteer JP, LaRiviere CA, Drugas GT et al (2013) Influence of surgeon experience, hospital volume, and specialty designation on outcomes in pediatric surgery. JAMA Pediatr 167(5):468–468

Youngwirth LM, Adam MA, Thomas SM et al (2018) Pediatric thyroid cancer patients referred to high-volume facilities have improved short-term outcomes. Surgery 163(2):361–366

Weiner JP, Abrams C (2011) The Johns Hopkins ACG® system technical reference guide version 10.0. John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Arim RG, Guevremont A, Kohen DE et al (2017) Exploring the Johns Hopkins aggregated diagnosis groups in administrative data as a measure of child health. Int J Child Health Hum Dev 10(1):19–29

Maltenfort MG, Chen Y, Forrest CB (2019) Prediction of 30-day pediatric unplanned hospitalizations using the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups risk adjustment system. Kamolz L-P, ed. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0221233

Matheson FI, Van Ingen T (2018) 2016 Ontario marginalization index: user guide. St. Michael’s Hospital. Joint Publication with Public Health Ontario, Toronto, ON

Austin PC (2017) A tutorial on multilevel survival analysis: methods. Models Appl Int Stat Rev 85(2):185–203

Keegan THM, Grogan RH, Parsons HM et al (2015) Sociodemographic disparities in differentiated thyroid cancer survival among adolescents and young adults in California. Thyroid 25(6):635–648

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada Permanent Resident Database (IRCC), Ontario Health (OH), Ontario Registrar General (ORG). The analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. Parts or whole of this material are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by IRCC current to May 2017. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions, and statements expressed in the material are those of the author(s), and not necessarily those of IRCC. Parts of this material are based on data and information provided by OH. The opinions, results, view, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of OH. No endorsement by OH is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this report are based on ORG information on deaths, the original source of which is ServiceOntario. The views expressed therein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of ORG or the Ministry of Government and Consumer Services. We thank the Toronto Community Health Profiles Partnership for providing access to the Ontario Marginalization Index.

Funding

Dr. AD Chesover was funded by the Canadian Paediatric Endocrine Group. This work was supported by the Pitbaldo Basic/Translational Discovery Grant from the Garron Family Cancer Centre, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto (JDW, NEW). This work was also supported through a Harry Barberian Research Grant from the University of Toronto Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery (NEW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. A Eskander has received research funds from Merck (2019) and has been a paid consultant for Bristol-Myers (2019) both of which were for work not related to this study. Dr. JD Wasserman was a paid consultant for Bayer (2019) for work unrelated to the study. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chesover, A.D., Eskander, A., Griffiths, R. et al. The Impact of Hospital Surgical Volume on Healthcare Utilization Outcomes After Pediatric Thyroidectomy. World J Surg 46, 1082–1092 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06456-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-022-06456-6