Abstract

Background

Feedback is a pivotal cornerstone and a challenge in psychomotor training. There are different teaching methodologies; however, some may be less effective.

Methods

A prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted in 130 medical students to compare the effectiveness of the video-guided learning (VLG), peer-feedback (PFG) and the expert feedback (EFG) for teaching suturing skills. The program lasted 4 weeks. Students were recorded making 3-simple stitches (pre-assessment and post-assessment). The primary outcome was a global scale (OSATS). The secondary outcomes were performance time, specific rating scale (SRS) and the impact of the intervention (IOI), defined as the variation between the final and initial OSATS and SRS scores.

Results

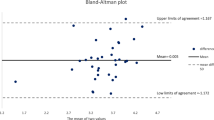

No significant differences were found between PFG and EFG in post-assessment results of OSATS, SRS scores or in the IOI for OSATS and SRS scores. Post-assessment results of PFG and EFG were significantly superior to VLG in OSATS and SRS scores [(19.8 (18.5–21); 16.6 (15.5–17.5)) and (20.3 (19.88–21); 16.8 (16–17.5)) vs (15.7 (15–16); 13.3 (12.5–14)) (p < 0.05)], respectively. The results of PFG and EFG were significantly superior to VLG in the IOI for OSATS [7 (4.5–9) and 7.4 (4.88–10) vs 3.5 (1.5–6) (p < 0.05)] and SRS scores [5.4 (3.5–7) and 6.3 (4–8.5) vs 3.1 (1.13–4.88) (p < 0.05)], respectively.

Conclusion

The video-guided learning methodology without any kind of feedback is not enough for teaching suturing skills compared to expert or peer feedback. The peer feedback methodology appears to be a viable alternative to handling the emerging demands in medical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Minha S, Shefet D, Sagi D, Berkenstadt H, Ziv A (2016) See one, sim one, do one"—a national pre-internship boot-camp to ensure a safer "student to doctor. Trans PLoS One 11(3):e0150122. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150122

Okuda Y, Bryson E, DeMaria S et al (2009) The utility of simulation in medical education: what is the evidence? Mt Sinai J Med 76(4):330–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/msj.20127

Issenberg S, McGaghie W, Petrusa E et al (2005) Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 27:10–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046924

Van de Ridder J, Stokking K, McGaghie W et al (2008) What is feedback in clinical education? Med Edu 42:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02973.x

Burns C (2015) Using debriefing and feedback in simulation to improve participant performance: an educator’s perspective. Int J Med Edu 6:118–120. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.55fb.3d3a

Gaunt A, Patel A, Rusius V et al (2017) ‘Playing the game’: how do surgical trainees seek feedback using workplace-based assessment? Med Edu 51:953–962. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13380

Aggarwal R, Darzi A (2006) Technical-skills training in the twenty first century. N Engl J Med 355:2695–2696. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe068179

Boza C, Leon F, Buckel E et al (2017) Simulation-trained junior residents perform better than general surgeons on advanced laparoscopic cases. Surg Endosc 31(1):135–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4942-6

Champagne B (2013) Effective teaching and feedback strategies in the OR and beyond. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 26(4):244–249. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1356725

Choy I, Okrainec A (2010) Simulation in surgery: perfecting the practice. Surg Clin North Am 90(3):457–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2010.02.011

Preece R, Dickinson E, Sherif M et al (2015) Peer-assisted teaching of basic surgical skills. Med Edu Online 3(20):27579. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.27579

Vogel D, Harendza S (2016) Basic practical skills teaching and learning in undergraduate medical education—a review on methodological evidence. GMS J Med Edu. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001063

Bochenska K, Milad M, DeLancey JO et al (2018) Instructional video and medical student surgical knot-tying proficiency: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Med Edu 4(1):e9. https://doi.org/10.2196/mededu.9068

Lwin A, Lwin T, Naing P et al (2018) Self-directed interactive video-based instruction versus instructor-led teaching for Myanmar house surgeons: a randomized noninferiority. Trial J Surg Edu 75(1):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.004

Nousiainen M, Brydges R, Backstein D et al (2008) Comparison of expert instruction and computer-based video training in teaching fundamental surgical skills to medical students. Surgery 143:539–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2007.10.022

Pilieci S, Salim S, Heffernan D et al (2018) A Randomized controlled trial of video education versus skill demonstration: which is more effective in teaching sterile surgical technique? Surg Infect 19(3):303–312. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2017.231

Summers A, Rinehart G, Simpson D et al (1999) Acquisition of surgical skills: a randomized trial of didactic, videotape, and computer-based training. Surgery 126:330–336

Xeroulis G, Park J, Moulton C et al (2007) Teaching suturing and knot-tying skills to medical students: a randomized controlled study comparing computer-based video instruction and (concurrent and summary) expert feedback. Surgery 141(4):442–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2006.09.012

Lockspeiser T, O'Sullivan P, Teherani A et al (2008) Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Health Sci Edu Theory Pract 13(3):361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-006-9049-8

Heckmann J, Dütsch M, Rauch C et al (2008) Effects of peer-assisted training during the neurology clerkship: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Neurol 15(12):1365–1370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02317.x

Knobe M, Munker R, Sellei R et al (2010) Peer teaching: A randomised controlled trial using student-teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Edu 44(2):148–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03557.x

Steele D, Medder J, Turner P (2000) A comparison of learning outcomes and attitudes in student- versus faculty-led problem-based learning: an experimental study. Med Edu 34:23–29. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00460.x

Wong J, Waldrep T, Smith T (2007) Formal peer-teaching in medical school improves academic performance: the MUSC supplemental instructor program. Teach Learn Med 19:216–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330701364551

Bennett S, Morris S, Mirza S (2018) Medical students teaching medical students surgical skills: the benefits of peer-assisted learning. J Surg Edu 75:1471–1474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.03.011

Hughes T, Jiwaji Z, Lally K et al (2010) Advanced cardiac resuscitation evaluation (ACRE): a randomised single-blind controlled trial of peer-led versus expert-led advanced resuscitation training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 18:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-18-3

Lemke M, Lia H, Gabinet-Equihua A et al (2020) Optimizing resource utilization during proficiency-based training of suturing skills in medical students: a randomized controlled trial of faculty-led, peer tutor-led, and holography-augmented methods of teaching. Surg Endosc 34(4):1678–1687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-06944-2

Saleh M, Sinha Y, Weinberg D (2013) Using peer-assisted learning to teach basic surgical skills: medical students' experiences. Med Edu Online 18:21065. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.21065

Vaughn C, Kim E, O’Sullivan P et al (2016) Peer video review and feedback improve performance in basic surgical skills. Am J Surg 211:355–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.034

Ilgen J, Ma I, Hatala R, Cook D (2015) A systematic review of validity evidence for checklists versus global rating scales in simulation-based assessment. Med Edu 49:161–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12621

Martin J, Regehr G, Reznick R et al (1997) Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg 84:273–278. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x

Giavarina D (2015) Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med 25:141–151. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2015.015

Marrugat Calculadora de tamaño muestral GRANMO. Barcelona. España: Institut Municipal d’Investigació Mèdica. 2012 [updated Versión 7.12 Abril 2012]. https://www.imim.cat/ofertadeserveis/software-public/granmo/. Accessed 21 Feb 2020

Alvarado J, Henríquez J, Castillo R et al (2015) A pioneer simulation curriculum of suture technique training for medical students. Rev Chi de Cir 67:480–485. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-40262015000500004

Dwan K, Li T, Altman DG, Elbourne D (2019) CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised crossover trials. BMJ 366:l437835

Chassin M, Galvin R (1998) The urgent need to improve health care quality. Inst Med Nat Roundtable Health Care Quality JAMA 80:1000–1005. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.11.1000.35

Scott D, Goova M, Tesfay S (2007) A cost-effective proficiency-based knot-tying and suturing curriculum for residency programs. J Surg Res 141:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.043

Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J (2007) Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach 29(6):558–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590701477449

Gordon J (2003) ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: one to one teaching and feedback. BMJ 326(7388):543–545. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7388.543

Funding

This study was financed and supported by a Chilean Research Grant (FONDECYT) regular 1171908 from “Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica de Chile” (CONICYT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Disclosure outside the scope of this work: Drs. Rodrigo Tejos, Pablo Achurra, Ruben Avila and Julian Varas received an educational grant from Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES): 2017 SAGES Research Grant. This research grant was finalized on March 2019.

Human and animal rights

The study was approved by the institution’s ethics committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tejos, R., Crovari, F., Achurra, P. et al. Video-Based Guided Simulation without Peer or Expert Feedback is Not Enough: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Simulation-Based Training for Medical Students. World J Surg 45, 57–65 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05766-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05766-x