Abstract

Introduction

There is paucity of literature describing type of injury and care for females in conflicts. This study aimed to describe the injury pattern and outcome in terms of surgery and mortality for female patients presenting to Médecins Sans Frontières Trauma Centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan, and compare them with males.

Materials and Methods

This study retrospectively analysed patient data from 17,916 patients treated at the emergency department in Kunduz between January and September 2015, before its destruction by aerial bombing in October the same year. Routinely collected data on patient characteristics, injury patterns, triage category, time to arrival and outcome were retrieved and analysed. Comparative analyses were conducted using logistic regression.

Results

Females constituted 23.6% of patients. Burns and back injuries were more common among females (1.4% and 3.3%) than among males (0.6% and 2.0%). In contrast, open wounds and thoracic injuries were more common among males (10.1% and 0.6%) than among females (5.2% and 0.2%). Females were less likely to undergo surgery (OR 0.60, CI 0.528–0.688), and this remained significant after adjustment for age, nature of injury, triage category, multiple injuries and delay to arrival (OR 0.80, CI 0.690–0.926). Females also had lower unadjusted odds of mortality (OR 0.49, CI 0.277–0.874), but this was not significant in the adjusted analysis (OR 0.81, CI 0.446–1.453).

Conclusion

Our main findings suggest that females seeking care at Kunduz Trauma Centre arrived later, had different injury patterns and were less likely to undergo surgery as compared to males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 4.5 million people die globally from injuries every year, accounting for 8% of global deaths [1]. About 90% of those deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) [2]. While most injuries, both globally and in LMIC, are due to road traffic injuries, self-harm, non-conflict-related interpersonal violence, falls and drowning, an increasing proportion is due to conflict [3]. Studies have documented that over 35% of casualties in armed conflicts are civilian [4,5,6,7]. The tendency in modern conflicts to directly target civilians, including aerial attacks on schools and hospitals, may explain the increasing burden of civilian trauma [8,9,10]. An example is the 2018 deliberate target of thousands of civilians in the conflict in eastern Ghouta, Syria [11]. Studies indicate that among civilians, females are twice as likely to die from air bombardments and other ordnance and have almost five times the odds of dying from chemical weapons as compared to males [12]. However, despite these findings and the fact that up to 22% of civilian casualties are female, there are few studies investigating trauma care outcomes for females [6, 7, 12,13,14].

In 2011, the international, independent, medical humanitarian organization Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) opened Kunduz Trauma Centre (KTC) in northern Afghanistan [15,16,17,18]. KTC provided essential trauma services free of charge until it was destroyed by a US airstrike in October 2015, resulting in 42 deaths and 30 injured including both staff and patients [16, 17]. There have been several publications using data from Kunduz, but to date there have been no studies specifically investigating female patients [19,20,21,22]. In addition, studies on outcome in terms of surgery and mortality are either inconclusive or lack presentation of gender differences [21, 23, 24]. This study utilized existing data from KTC to gain critical knowledge on how females as a group were affected by trauma in this conflict setting. The aim was to describe the injury pattern, frequency of surgery and mortality for female patients seeking care at the emergency department (ED) at MSF Trauma Centre in Kunduz and to compare with male patients.

Materials and methods

KTC was located in Kunduz city, Afghanistan’s fifth largest city, situated in the province of Kunduz with one million inhabitants [25]. Prior to the establishment of KTC, trauma patients had to travel to either Kabul, Afghanistan or Pakistan to receive trauma care [26]. The distance to Kabul, the nearest of the two, is over 330 km [27]. During its functional years (2011–2015), more than 15,000 surgeries were performed and around 68,000 emergency consultations were conducted at the centre [17].

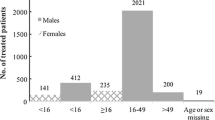

The study included all patients ≤ 80 years of age treated at KTC between 1 January 2015 and 18 September 2015. Due to incompleteness of available data, patients who presented prior to this time period were not included in our study. A total of 18,082 patient visits were recorded at the ED during the study period. Patients with missing data (n = 47) or who were dead on arrival (n = 119) were excluded (see Fig. 1).

Surgery and mortality were chosen as outcome measures owing to inconsistent results from previous studies measuring these outcomes [21, 23, 24]. Further, previous studies from KTC indicated that there were limitations in the availability of other variables collected at the centre [19, 22]. Injury pattern included cause of hospitalization, nature of injury, body region of injury and presence of multiple injuries. Covariates included age, nature of injury, triage category (see “Appendix”), multiple injuries and delay to arrival, all but the first selected as they are determinants for injury severity scoring. The covariates were used to characterize the study sample and to adjust the association between gender and outcome in regression analyses. Surgery was defined as all procedures performed, from minor wound treatment to major laparotomies in an operating room and requiring anaesthesia. Mortality was defined as all patients who were alive on arrival but later died while in care at the centre.

This study utilized routinely collected patient data which were recorded using a standardized form used across all MSF missions. The data were entered in a logbook and then transferred into an electronic database (Microsoft Excel) on a monthly basis. The database was then transmitted to the MSF headquarters in Brussels where it was reviewed for accuracy. Discrepancies were addressed and corrected after contact with program personnel involved in data entry.

Statistical analysis was performed using R 3.3.2. (The R Foundation, R Core Team, 1020 Vienna, Austria) [28]. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were performed according to the type of variables considered. First, an unadjusted analysis using logistic regression was used for mortality and surgery, with gender as the only independent variable. Second, an adjusted analysis was conducted in which age, nature of injury, triage category, multiple injuries and delay to arrival were added as independent variables. Values were given as mean (SD) or median (IQR) when applicable. Confidence intervals were set at 95% with a 5% significance.

Results

A total of 17,916 patients were included in this study, out of which 23.6% were female (Fig. 1, Table 1). Age ranged from between < 1 to 80 years, and 70.7% were under the age of 30. Children (< 15 years) represented 35.5% of all patients while 4.8% were over the age of 60. The median age was 20 years (IQR 8.0–40.0) for females and 19 years (IQR 11.0–30.0) for males.

A total of 53.3% were triaged as yellow on arrival (female 57.6%, male 52.0%). The percentage of patients triaged as red or orange was lower for females (21.8%) than for males (30.8%). A lower percentage of females arrived within the first hour after injury as compared to males (19.1% vs. 25.7%), and a higher percentage arrived more than one day after injury (26.6% vs. 18.9%).

A total of 6.9% of females were hospitalized due to violence-related injuries (assault, bombs, guns, knives and mines), corresponding to half that for males (14.0%). Non-conflict-related injuries for both genders included road traffic injuries (16.2%), burns (0.8%) and a large proportion (70.6%) of unspecified injuries entered as “Accident–Others”.

A total of 101 patients (0.6%) died. Of those, 13 (12.9%) were female, representing 0.3% of all females seeking care. In our study population, 1741 (9.7%) patients underwent surgery, out of which 283 (16.3%) were female. Thus, 6.7% of all females underwent surgery compared to 10.7% of males. The percentage of burns among females was more than double that of men (1.4% vs. 0.6%). Males had almost double the percentage of open wounds as compared to females (10.1% vs. 5.2%). Back injuries were more common in females (3.3% vs. 2.0%), while men had a three times higher risk of injuries to the thorax (0.6% vs. 0.2%). Multiple surgical interventions were conducted in 36% of all female patients and for 42% of male patients.

In both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses for surgery (Table 2 and Table 3), females had significantly lower odds of undergoing surgery compared to males (unadjusted OR of 0.60, p < 0.001, CI 0.53–0.69, adjusted OR 0.80, p = 0.003, CI 0.69–0.93). The analysis also showed that females had a lower unadjusted odds ratio of dying (OR 0.49, p = 0.016, CI 0.28–0.87) (Table 4). However, when adjusted, this was no longer significant (OR 0.81, p = 0.47, CI 0.45–1.45) (Table 5).

Discussion

Our main findings suggest that female trauma patients arrived later than men, had a different injury pattern and were less likely to undergo surgery. The cause of hospitalization showed a surprisingly small proportion of conflict-related injuries in this high-intense conflict area. One explanation could be that patients in challenging contexts may hesitate to report their injuries as being due to assault but it could also be explained by impaired access and that patients might have died before arrival. Our results also showed that the proportion of conflict-related injuries in females was half compared to males. This could be explained by the way of warfare where females are less involved. However, although “Accident–Others” is not a group of violent trauma, the largeness and width of the group add uncertainty to all results under “cause of hospitalisation” and no certain conclusion can therefore be drawn based on this category. The differences in injury patterns between genders were consistent with other studies from similar as well as different settings to Kunduz [7, 12, 29]. However, overall, gender differences in categories describing injury pattern, i.e. nature of injury and body region of injury, were small.

Due to local traditions prevailing in Afghanistan, females have limited movement outside the household and depend on males for transportation to KTC. These factors might explain why fewer females visited the ED, as well as the differences in injury pattern (double the percentage of burns could be explained by them doing more of the cooking), and it might also explain why females arrived later than men to the hospital. However, only 24.1% of all patients arrived at KTC within an hour of injury, indicating that there were significant limitations in the overall access to KTC. Another factor that indicates impaired access in Kunduz is the very low mortality of 0.6% which is only a third of the median mortality rate demonstrated in a WHO systematic review of EDs in LMICs (1.8%, IQR 0.2–5.1) [30]. To enable comparison with trauma care studies, the in-patient hospital mortality was calculated and found to be 2.8% (see Table 6). However, beyond ascertaining that a death had occurred in the ED, or following admittance to the hospital, the data did not provide sufficient detail to calculate 24 h- and 30-day mortality. The in-patient hospital mortality of 2.8% is significantly lower than the mortality rates described in a US military medical facility in Afghanistan, where non-war-related conditions had a 3.6% mortality and war-related mortality was 5.11% [31]. Moreover, the in-hospital mortality in KTC is almost three times lower than the in-hospital mortality of 18 level 1 trauma centres in the USA [32]. This implies that the most critically injured patients in Kunduz may have died prior to reaching KTC, indicating a significant gap in prehospital care and availability of rapid transport.

The adjusted odds of surgery remained significantly lower in females as compared to males. This finding suggests that females were less likely to undergo surgery even if they had as severe trauma and the same type of injuries as their male counterparts. Our data do not allow us to determine the cause of this difference, but future prospective research should attempt to assess this. We can only speculate to why the OR is lower for females after adjustment. It could be that all indicators for severity were not considered during the adjusted analysis for risk of surgery or that the adjustment itself had flaws. The literature reveals conflicting conclusions with respect to surgical interventions for females. In our study, females represented 16.3% of all surgeries. This is in accordance with a study by Forrester et al. [23] where females in a number of MSF hospitals around the world accounted for between 16 and 41% of the operative interventions. Andersson et al. [24] found that females tended to be younger and required more surgeries than male patients when assessing at the female surgical outcome rather than the female percentage of all surgeries. However, our results still indicate a lower surgical rate for females.

This study is subject to a number of limitations. First, since the study was retrospective, it was limited to existing data with risk of bias and unmeasured confounding, as well as errors in data entry. Second, the unknown causes of injury in the group “Accident–Others” are a source of inaccuracy. Third, given the austere environment in which this facility operated, transcription errors may have occurred. However, due to the random nature of this type of error, any impact on the results of this study is likely to be limited. Fourth, no measurement for injury severity was used due to limitations in our data. Fifth, two different triage systems were used, SATS regularly and START when there were mass casualty incidents (MCI). Only approximately 100 patients were MCI’s and therefore triaged using START minor errors in our results cannot be excluded. Lastly, there was no provision made in the data regarding whether patients are civilian or combatant, which could have provided additional insight concerning reasons for gender differences. Despite above, we still think the results are accurate and provide essential information that may help to improve trauma care for females in conflict settings.

Further research into what particular risks females are subject to is essential to guide preventative measures. The extent to which our results are generalizable is uncertain, and our understanding of female trauma patients in conflicts would therefore gain from additional studies in this setting. Moreover, working to improve systematic trauma surveillance in-country will allow for future retrospective studies to determine the epidemiology of female trauma patients. These are all crucial to guide public health interventions to improve the situation for females in conflict areas. The issue of systematic, high-quality data collection which enables both programmatic and scientific research in conflict environments is an urgent one. To enable quality studies yielding actionable results to the benefit of civilians in conflict environments, the authors recommend implementing data collection systems which provide more detailed patient data. However, merely including more variables is of little value if data collection routines are not followed. Therefore, any measure to improve systematic data collection must be coupled with the incentives, manpower and IT infrastructure needed to ensure consistent data collection. MSF is aware of this and efforts are constantly being done to improve the reliability and the accuracy of collected data [33].

Notes

MCI: Multiple/mass casualty incident.

References

Collaborators GBDCoD (2018) Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392(10159):1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32203-7 (Epub 2018/11/30)

WHO (2014) Injuries and violence: the facts. WHO, Geneva. [cited 2018 Jan 26]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/149798/1/9789241508018_eng.pdf

Collaborators GBDDaH (2017) Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1260–1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32130-x (Epub 2017/09/19)

Aboutanos MB, Baker SP (1997) Wartime civilian injuries: epidemiology and intervention strategies. J Trauma 43(4):719–726 (Epub 1997/11/14)

Meddings DR (2001) Civilians and war: a review and historical overview of the involvement of non-combatant populations in conflict situations. Med Confl Surviv 17(1):6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623690108409551 (Epub 2001/05/08)

Zwierzchowski J, Tabeau E (2010) The 1992–1995 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina: census-based multiple system estimation of casualties’ undercount. Households in Conflict Network and Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, p 539

Guha-Sapir D, Schluter B, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Lillywhite L, Hicks MH (2018) Patterns of civilian and child deaths due to war-related violence in Syria: a comparative analysis from the Violation Documentation Center dataset, 2011–2016. Lancet Glob Health. 6(1):e103–e110. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30469-2 (Epub 2017/12/12)

Stokes C (2016) One year after Kunduz: Battlefields without doctors, in wars without limits Geneva, Switzerland: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). [cited 2018 Jan 22]. http://www.msf.org/en/article/one-year-after-kunduz-battlefields-without-doctors-wars-without-limits

Hakimoglu S, Karcioglu M, Tuzcu K, Davarci I, Koyuncu O, Dikey I et al (2015) Assessment of the perioperative period in civilians injured in the Syrian Civil War. Braz J Anesthesiol 65(6):445–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2014.03.003 (Epub 2015/11/29)

OHCHR (2016) Statement by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic on the aerial attack against school complex in Haas village, Idlib. Geneva, Switzerland: Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. [cited 2018 Mar 1]. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=20786&LangID=E

MSF (2018) Syria: an outrageous, relentless mass casualty disaster in East Ghouta Geneva, Switzerland: Médecins Sans Frontières. [cited 2018 Jan 20]. http://www.msf.org/en/article/syria-outrageous-relentless-mass-casualty-disaster-east-ghouta

Guha-Sapir D, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Hicks MH, Donneau AF, Coutts A, Lillywhite L et al (2015) Civilian deaths from weapons used in the Syrian conflict. BMJ. 351:4736. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4736 (Epub 2015/10/01)

Klimo P Jr, Ragel BT, Jones GM, McCafferty R (2015) Severe pediatric head injury during the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Neurosurgery. 77(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000743 (discussion Epub 2015/03/27)

UNAMA (2018) Afghanistan, protection of civilians in armed conflict. Annual Report 2017

MSF (2018) MSF history Geneva, Switzerland: Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). [cited 2018 Jan 24]. http://www.msf.org/en/msf-history

MSF (2015). Attack on Kunduz Trauma Centre: AFGHANISTAN. Geneva, Switzerland: Mèdecins Sans Frontières (MSF). [cited 2018 Jan 22]. http://kunduz.msf.org/

MSF (2015). Initial MSF internal review: Attack on Kunduz Trauma Centre: Afghanistan Geneva, Switzerland. [cited 2018 Jan 22]. http://kunduz.msf.org/pdf/20151030_kunduz_review_EN.pdf

MSF (2018) MSF charter and principles: Médecins sans Frontières. [cited 2018 Feb 10]. http://www.msf.org/en/msf-charter-and-principles

Hemat H, Shah S, Isaakidis P, Das M, Kyaw NTT, Zaheer S et al (2017) Before the bombing: high burden of traumatic injuries in Kunduz Trauma Center, Kunduz, Afghanistan. PLoS ONE 12(3):e0165270

Trelles M, Stewart BT, Hemat H, Naseem M, Zaheer S, Zakir M et al (2016) Averted health burden over 4 years at Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Trauma Centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan, prior to its closure in 2015. Surgery 160(5):1414–1421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.024 (Epub 2016/10/30)

Valles P, Van den Bergh R, van den Boogaard W, Tayler-Smith K, Gayraud O, Mammozai BA et al (2016) Emergency department care for trauma patients in settings of active conflict versus urban violence: all of the same calibre? Int Health 8(6):390–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw035 (Epub 2016/11/05)

Gohy B, Ali E, Van den Bergh R, Schillberg E, Nasim M, Naimi MM et al (2016) Early physical and functional rehabilitation of trauma patients in the Medecins Sans Frontieres trauma centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan: luxury or necessity? Int Health 8(6):381–389. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihw039 (Epub 2016/10/16)

Forrester JD, Forrester JA, Basimouneye JP, Tahir MZ, Trelles M, Kushner AL et al (2017) Sex disparities among persons receiving operative care during armed conflicts. Surgery. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.03.001 (Epub 2017/04/13)

Andersson P, Muhrbeck M, Veen H, Osman Z, von Schreeb J (2017) Hospital workload for weapon-wounded females treated by the international committee of the red cross: more work needed than for males. World J Surg 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4160-y (Epub 2017/08/11)

UN-HABITAT (2015) State of Afghan cities: UN-HABITAT. [cited 2018 Jan 23]. http://unhabitat.org/books/soac2015/

MSF (2012) Trauma care where there was none in Northern Afghanistan Geneva, Switzerland: Médecins Sans Frontières. [cited 2018 Feb 12]. http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/news-stories/slideshow/trauma-care-where-there-was-none-northern-afghanistan

Google (2018) Google maps California, United States: Google. [cited 2018 Feb 22]. https://www.google.se/maps

Team RC (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [cited 2018 Jan 25]. https://www.r-project.org/

Bolandparvaz S, Yadollahi M, Abbasi HR, Anvar M (2017) Injury patterns among various age and gender groups of trauma patients in southern Iran: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 96(41):e7812. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000007812 (Epub 2017/10/12)

Obermeyer Z, Abujaber S, Makar M, Stoll S, Kayden SR, Wallis LA et al (2015) Emergency care in 59 low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 93(8):577–586. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.14.148338 (Epub 2015/10/20)

Weeks SR, Oh JS, Elster EA, Learn PA (2018) Humanitarian surgical care in the US military treatment facilities in Afghanistan from 2002 to 2013. JAMA Surg 153(1):84–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3142 (Epub 2017/09/14)

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL et al (2006) A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med 354(4):366–378. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa052049

Chu K, Stokes C, Trelles M, Ford N (2011) Improving effective surgical delivery in humanitarian disasters: lessons from Haiti. PLoS Med 8(4):e1001025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001025 (Epub 2011/05/05)

Acknowledgements

First, we would like to acknowledge the brave staff that under difficult security situations courageously worked at the Trauma Centre in Kunduz. We especially think of the 42 staff and patients that lost their lives following the bombing on October 3rd 2015. Bombing of hospitals is a war crime that must be brought to justice!

Funding

Martin Gerdin Wärnberg, Maximilian Nerlander and Johan von Schreeb were funded by a research grant from the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Studies conducted in resources scarce, complex conflict environments include several ethical considerations. We are convinced that research can shed light on the problems the populations are exposed to. But careful ethical considerations are needed. This study was retrospective and did not affect the treatment of any patient. The specific group studied did not gain from this study, but increased knowledge of trauma care in conflicts is crucial to adapt and improve care. This research fulfilled the exemption criteria set by the Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Review Board for a posteriori analyses of routinely collected clinical data and thus did not require by the MSF Ethical Review board. It was conducted with permission from Medical Director, Operational Centre Brussels, Médecins Sans Frontières. This research also received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Afghanistan Ministry of Public Health (ref 444796).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Triage Colour

Appendix: Triage Colour

During normal activities in the ED, the SATS (South African Triage Scale) is used. The SATS colour code is the following:

Red | Immediate emergency management is required (resuscitation room) |

Orange | Very urgent management is required within 10 min |

Yellow | Urgent management is required within 1 h |

Green | Management within 4 h is required, but no urgency |

Blue | Dead on arrival |

In case of a MCI,Footnote 1 MSF recommends the START scale (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment). The START colour code is the following:

Red | Required immediate medical attentiona |

Yellow | Required delayed medical attention within 6 h |

Green | Required minimal medical attention when all higher priority patients have been treated/evacuated |

Black | Dead on arrivalb |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tounsi, L.L., Daebes, H.L., Gerdin Wärnberg, M. et al. Association Between Gender, Surgery and Mortality for Patients Treated at Médecins Sans Frontières Trauma Centre in Kunduz, Afghanistan. World J Surg 43, 2123–2130 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05015-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05015-w