Abstract

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) reduces complications and hospital stay in colorectal surgery. Thereafter, ERAS principles were extended to liver surgery. Previous implementation of an ERAS program in colorectal surgery may influence patients undergoing liver surgery in a non-ERAS setting, on the same ward. This study aimed to test this hypothesis.

Methods

Retrospective analysis based on prospective data of the adherence to the institutional ERAS-liver protocol (compliance) in three cohorts of consecutive patients undergoing elective liver surgery, between June 2010 and July 2014: before any ERAS implementation (pre-ERAS n = 50), after implementation of ERAS in colorectal (intermediate n = 50), and after implementation of ERAS in liver surgery (ERAS-liver n = 74). Outcomes were functional recovery, postoperative complications, hospital stay, and readmissions.

Results

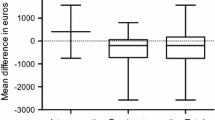

The three groups were comparable for demographics; laparoscopy was more frequent in ERAS-liver (p = 0.009). Compliance with the enhanced recovery protocol increased along the three periods (pre-ERAS, intermediate, and ERAS-liver), regardless of the perioperative phase (pre-, intra-, or postoperative). ERAS-liver group displayed the highest overall compliance rate with 73.8 %, compared to 39.9 and 57.4 % for pre-ERAS and intermediate groups (p = 0.072/0.056). Overall complications were unchanged (p = 0.185), whereas intermediate and ERAS-liver groups showed decreased major complications (p = 0.034). Consistently, hospital stay was reduced by 2 days (p = 0.005) without increased readmissions (p = 0.158).

Conclusions

The previous implementation of an ERAS protocol in colorectal surgery may induce a positive impact on patients undergoing non-ERAS-liver surgery on the same ward. These results suggest that ERAS is safely applicable in liver surgery and associated with benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rawlinson A, Kang P, Evans J et al (2011) A systematic review of enhanced recovery protocols in colorectal surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 93:583–588

Wind J, Polle SW, Fung Kon, Jin PH et al (2006) Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. Br J Surg 93:800–809

Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH et al (2010) The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Nutr 29:434–440

Kehlet H (2011) Surgery: fast-track colonic surgery and the ‘knowing-doing’ gap. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8:539–540

Spanjersberg WR, Reurings J, Keus F et al (2011) Fast track surgery versus conventional recovery strategies for colorectal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(2), CD007635. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007635.pub2

Findlay JM, Gillies RS, Millo J et al (2014) Enhanced recovery for esophagectomy: a systematic review and evidence-based guidelines. Ann Surg 259:413–431

Hall TC, Dennison AR, Bilku DK et al (2012) Enhanced recovery programmes in hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 94:318–326

van Dam RM, Hendry PO, Coolsen MM et al (2008) Initial experience with a multimodal enhanced recovery programme in patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg 95:969–975

Hughes MJ, McNally S, Wigmore SJ (2014) Enhanced recovery following liver surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 16:699–706

Jones C, Kelliher L, Dickinson M et al (2013) Randomized clinical trial on enhanced recovery versus standard care following open liver resection. Br J Surg 100:1015–1024

Coolsen MM, Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Dam RM et al (2013) A systematic review of outcomes in patients undergoing liver surgery in an enhanced recovery after surgery pathways. HPB (Oxford) 15:245–251

Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J et al (2009) Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg 144:961–969

Roulin D, Donadini A, Gander S et al (2013) Cost-effectiveness of the implementation of an enhanced recovery protocol for colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 100:1108–1114

Roulin D, Blanc C, Muradbegovic M et al (2014) Enhanced recovery pathway for urgent colectomy. World J Surg 38:2153–2159. doi:10.1007/s00268-014-2518-y

Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Schwenk W et al (2013) Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colonic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. World J Surg 37:259–284. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.013

Nygren J, Thacker J, Carli F et al (2013) Guidelines for perioperative care in elective rectal/pelvic surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. World J Surg 37:285–305. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2012.08.012

Lassen K, Coolsen MM, Slim K et al (2012) Guidelines for perioperative care for pancreaticoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Clin Nutr 31:817–830

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J et al (2013) The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg 258:1–7

Mentha G, Majno PE, Andres A et al (2006) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and resection of advanced synchronous liver metastases before treatment of the colorectal primary. Br J Surg 93:872–878

Gustafsson UO, Hausel J, Thorell A et al (2011) Adherence to the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Arch Surg 146:571–577

Maessen J, Dejong CH, Hausel J et al (2007) A protocol is not enough to implement an enhanced recovery programme for colorectal resection. Br J Surg 94:224–231

Wong-Lun-Hing EM, van Dam RM, Heijnen LA et al (2014) Is current perioperative practice in hepatic surgery based on enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles? World J Surg 38:1127–1140. doi:10.1007/s00268-013-2398-6

Connor S, Cross A, Sakowska M et al (2013) Effects of introducing an enhanced recovery after surgery programme for patients undergoing open hepatic resection. HPB (Oxford) 15:294–301

Stoot JH, van Dam RM, Busch OR et al (2009) The effect of a multimodal fast-track programme on outcomes in laparoscopic liver surgery: a multicentre pilot study. HPB (Oxford) 11:140–144

Hammond JS, Humphries S, Simson N et al (2014) Adherence to enhanced recovery after surgery protocols across a high-volume gastrointestinal surgical service. Dig Surg 31:117–122

Dasari BV, Rahman R, Khan S et al (2015) Safety and feasibility of an enhanced recovery pathway after a liver resection: prospective cohort study. HPB (Oxford) 17:700–706

Schultz NA, Larsen PN, Klarskov B et al (2013) Evaluation of a fast-track programme for patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg 100:138–143

Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I et al (2011) Perioperative fasting in adults and children: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 28:556–569

Cerantola Y, Hubner M, Grass F et al (2011) Immunonutrition in gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg 98:37–48

Hill J, Treasure T, Guideline Development Group (2010) Reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) in patients admitted to hospital: summary of the NICE guideline. Heart 96:879–882

Song F, Glenny AM (1998) Antimicrobial prophylaxis in colorectal surgery: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg 85:1232–1241

Kranke P, Eberhart LH (2011) Possibilities and limitations in the pharmacological management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Eur J Anaesthesiol 28:758–765

Giglio MT, Marucci M, Testini M et al (2009) Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy and gastrointestinal complications in major surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth 103:637–646

Brooke-Smith M, Figueras J, Ullah S et al (2015) Prospective evaluation of the International Study Group for Liver Surgery definition of bile leak after a liver resection and the role of routine operative drainage: an international multicentre study. HPB (Oxford) 17:46–51

Nelson R, Edwards S, Tse B (2007) Prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(3), CD004929. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004929.pub3

Convertino VA, Cardiovascular consequences of bed rest (1997) effect on maximal oxygen uptake. Med Sci Sports Exerc 29:191–196

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by all members of the enhanced recovery team in Lausanne, and especially the dedicated surgical nursing team with their leaders V. Addor, N. Zehnder, and A. Jannot. A particular attention is paid to the outstanding efforts and contribution achieved by V. Addor for the data management. Institutional financial support: Department of Visceral Surgery, University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV), Switzerland.

Author contribution

Ismail Labgaa: conception and design, analysis, interpretation and writing. Ghada Jarrar: collection of data and interpretation. Gaetan-Romain Joliat: conception and design, interpretation and critical revision. Pierre Allemann: conception and design, interpretation and critical revision. Sylvain Gander: conception and design, interpretation and critical revision. Catherine Blanc: collection of data, interpretation and critical revision. Martin Hübner: conception and design, interpretation, drafting and critical revision. Nicolas Demartines: conception and design, interpretation and major editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests and no sources of support and funding for this work.

Additional information

Ismail Labgaa and Ghada Jarrar have contributed equally.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 5.

Compliance rate of each ERAS items fro the three comparative groups. The bars indicate the percentage of patients who adhered to the individual measures of the ERAS protocol. Results are presented for the three comparative groups “pre-ERAS (green)”, “intermediate (red)” and ERAS-liver (blue). Asterisk indicates statistical significance: p < 0.05

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Labgaa, I., Jarrar, G., Joliat, GR. et al. Implementation of Enhanced Recovery (ERAS) in Colorectal Surgery Has a Positive Impact on Non-ERAS Liver Surgery Patients. World J Surg 40, 1082–1091 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3363-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-015-3363-3