Abstract

Purpose

Implant loosening represent the most common indication for stem revision in hip revision arthroplasty. This study compares femoral bone loss and the risk of initial revisions between cemented and uncemented loosened primary stems, investigating the impact of fixation method at primary implantation on femoral bone defects.

Methods

This retrospective study reviewed 255 patients who underwent their first revision for stem loosening from 2010 to 2022, receiving either cemented or uncemented stem implants. Femoral bone loss was preoperatively measured using the Paprosky classification through radiographic evaluations. Kaplan-Meier analysis estimated the survival probability of the original stem, and the hazard ratio assessed the relative risk of revision for uncemented versus cemented stems in the first postoperative year and the following two to ten years.

Results

Cemented stems showed a higher prevalence of significant bone loss (type 3b and 4 defects: 32.39% vs. 2.72%, p < .001) compared to uncemented stems, which more commonly had type 1 and 2 defects (82.07% vs. 47.89%, p < .001). In our analysis of revision cases, primary uncemented stems demonstrated a 20% lower incidence of stem loosening in the first year post-implantation compared to cemented stems (HR 0.8; 95%-CI 0.3-2.0). However, the incidence in uncemented stems increased by 20% during the subsequent years two to ten (HR 1.2; 95%-CI 0.7–1.8). Septic loosening was more common in cemented stems (28.17% vs. 10.87% in uncemented stems, p = .001). Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated a modestly longer revision-free period for cemented stems within the first ten years post-implantation (p < .022).

Conclusion

During first-time revision, cemented stems show significantly larger femoral bone defects than uncemented stems. Septic stem loosening occurred 17.30% more in cemented stems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite improved implant survival of total hip arthroplasties (THA) over the last years, the number of replacement surgeries continues to increase [1].

The most common indication for stem revision is loosening of the primary prostheses [2, 3]. This can be due to aseptic or septic conditions [4]. The most common cause of aseptic stem loosening occurs due to particle-induced reactions caused by the release of small abrasive particles, which can cause local, chronic inflammation [5, 6]. As a result of macrophage activation and induced osteoclastogenesis, peri-implant osteolysis and associated stem loosening and periprosthetic bone resorption may occur [7, 8]. During this process, a periprosthetic membrane develops between the loosened stem and the bone [9].

The incidence of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) following primary total hip arthroplasty is approximately 1.05% in database studies and 1.74% in clinic studies [10], with a recent increase in PJI cases [11,12,13,14]. The main causes include intraoperative contamination, postoperative infection, hematogenous dissemination, chronic skin infection, and previous prosthetic infection [15, 16]. Infection can result in bone resorption, density loss, defects, and periprosthetic fractures, leading to serious complications [17, 18].

Implant fixation choice is key in hip replacement surgery, with cemented and uncemented methods available.

The use of cement might influence bone remodeling, including osteoclastogenesis, potentially leading to reduced stress and bone stimulation near the stem, which could decrease bone remodeling [19,20,21]. Cement can cause bone defects if unevenly distributed or degraded over time [19, 22]. However, outcomes vary among patients with cemented hip replacements, influenced by stem design, surgical technique, bone quality, and individual response [23,24,25].

In contrast, uncemented stems are theorized to maintain physiological stress patterns on the bone, thereby preserving remodeling activities [26, 27]. This study seeks to delineate the disparities in bone defect patterns between cemented and uncemented stems at the juncture of first-time revision.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study, approved by our institution’s ethics committee (EA4/129/23), analyzed 255 out of 1,365 first-time revision surgeries post-primary THA from January 2010 to December 2022, including cases from both our facility and external institutions. The study focused on aseptic and septic loosening of cemented and uncemented stems. PJI was determined using EBJIS criteria [28]. Exclusions included acetabular loosening, incomplete data, periprosthetic fractures, replacement of head/inlay, metallosis, painful THA, dislocations, impingements, leg length discrepancies, implant failures, and instability. Pre-revision femoral bone loss was classified using the Paprosky et al. classification, based on surgical reports and radiographs (Fig. 1). Data collected included implant survival times, THA indications, Paprosky classifications, and patient comorbidities.

a depicts a case of septic loosening in a patient with a left cemented primary stem and a substantial femoral defect, classified as Paprosky 3a. This patient underwent a two-stage stem revision process. b shows a Girdlestone situation following the removal of a primary THA. c illustrates the postoperative state after the insertion of an uncemented revision stem, specified by the SLR type from Smith & Nephew, and a revision cup of the TMT type from Zimmer.

Bone defect size assessment

Preoperative imaging studies, including pelvic overviews and axial hip radiographs taken before first-time revision surgery, were systematically reviewed. Two independent investigators, NW and SH, evaluated the size of femoral bone defects using the Paprosky classification (Fig. 2). In cases where consensus between NW and SH was not reached, a third independent surgeon was consulted.

femoral bone defect size according to Paprosky et al. [29]

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data as means and standard deviations. Associations were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s tests (p < .05). Normality of continuous variables was tested with Kolmogorov-Smirnov; normally distributed data (p > .05) used means, standard deviations, and parametric tests (t-Test), while non-normally distributed data used medians, quartiles, and nonparametric methods (Mann-Whitney-U test). Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis, and Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for confounders. All tests were two-tailed with a 5% significance level. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29, IBM Inc., and R for survival analysis.

Results

Patient selection is illustrated in Fig. 3. The study encompassed 255 patients (147 females, 108 males) with an average age of 73 years at the time of their first revision surgery. The study cohort was categorized into two groups based on the nature of stem loosening: 71 patients (27.84%) with cemented stems and 184 patients (72.16%) with uncemented stems, all of whom underwent stem replacement during the initial revision period from January 2010 to December 2022.

Demographic characteristics and clinical profiles are tabulated in Table 1.

The average age at primary surgery was similar for both cemented and uncemented stem loosening groups (63 vs. 60, p = .455). Patients with cemented stem loosening more frequently had higher ASA scores (3–4) than those with uncemented stems (52.11% vs. 39.13%, p = .298). CHD was more common in the cemented group (54.93% vs. 48.91%, p = .389), while renal failure incidence was 6% higher in the uncemented group (13.04% vs. 7.04%, p = .176). The initial diagnoses of primary and secondary osteoarthritis were similarly distributed in both groups (Table 1).

Comparative analysis of outcomes in cemented vs. uncemented stems for primary implantation and first-time revision in hip arthroplasty

At the time of primary implantation, osteoporosis was diagnosed in 14.08% of patients with cemented stems and 12.00% of those with uncemented stems (p = .646). The primary surgical approach was predominantly lateral, with 76.06% in the cemented group and 42.93% in the uncemented group (p < .001). Hip types indicated a majority of coxa norma with 74.65% in the cemented group versus 90.22% in the uncemented group (p < .001). Preoperative CCD angles averaged 125.85° for cemented and 127.38° for uncemented stems (p = .274). Dorr type B was most common, occurring in 91.55% of cemented stem cases and 70.11% of uncemented stem cases (p < .001).

During the first revision, aseptic loosening occurred more frequently in patients with uncemented stems compared to those with cemented stems (60.33% vs. 32.39%, p < .001). Conversely, septic loosening occurred 17.3% more often in the cemented stem group than in the uncemented cohort (28.17% vs. 10.87%, p = .001), while patients with cemented stems showed concurrent cup loosening more frequently than patients with uncemented stems (39.44% vs. 28.8%, p = .105) (Table 1). Cemented stems had a longer implant survival (mo.) than uncemented stems and were consequently revised for the first time later (143 vs. 90, p = .009). Furthermore, the mean operative time for the first revision procedure was extended by 37 min for those with cemented stems (165 vs. 128, p < .001).

Predominance of cemented and distal-anchored prostheses in initially cemented stems

In stem revisions, implant choice is influenced by bone defect size. Patients with original cemented stems often received another cemented implant or a distal-anchored revision stem. Data showed distinct implant preferences: 28.17% with initially cemented stems received a cementless Revitan stem versus 14.29% with uncemented stems (p = .009). Conversely, 18.31% with primary cemented stems got an uncemented SL-Plus-MIA stem, compared to 38.46% for primary uncemented stems (p = .003). Cemented VerSys stems were utilized in 16.90% of revisions involving primary cemented stems, as opposed to 1.10% of revisions for primary uncemented stems (p < .001). Similarly, 16.90% of initially cemented stems had a cementless SLR revision, rising to 29.12% for primary uncemented stems (p = .051). The cemented SPII Lubinus stem was chosen in 11.27% of cases with initially cemented stems, against 2.20% in uncemented (p = .002). This indicates a trend towards repeating cemented implants in patients with original cemented stems, while those with primary uncemented stems preferred uncemented revisions (Table 2).

Increased femoral bone resorption associated with cemented primary stem fixation

An evaluation of femoral bone integrity revealed that cemented stems exhibit a significantly higher prevalence of severe bone defects, with Paprosky et al.‘s type 4 and 3b defects observed in 32.39% of cases, in stark contrast to a mere 2.72% in uncemented stems before first-time revision (p < .001) (Table 2). The incidence of type 3a femoral bone defects was noted in 19.72% of cemented stems, compared to 15.22% associated with loosening of uncemented stems (p = .385). Conversely, the uncemented group demonstrated a predominance of milder type 1 and 2 defects, accounting for 82.07%, whereas such defects in the cemented cohort were noted in only 47.89% of cases (p < .001). This data highlights a distinct pattern and severity of bone loss that could be attributed to the method of stem fixation, both in aseptic and septic loosening conditions. Notably, cementation shows a significant correlation with advanced bone defect classes prior to initial revision surgery.

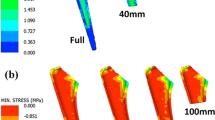

Our subanalysis showed that, under aseptic conditions, cemented stems exhibited severe bone defects (Paprosky type IIIB and IV) significantly more often—occurring in 43.14% of cases—compared to only 1.22% in uncemented stems (see Tables 3 and 4). The analysis of Paprosky type IIIA defects also revealed differences, type IIIA defects occurred in 23.53% of aseptic cemented stems, while they were found in 14.02% of cases in uncemented stems. Milder defects (Paprosky type I and II) were much more common in the group of uncemented stems under aseptic conditions, at 84.75% compared to 33.33% in cemented stems (Fig. 4).

Cemented stem fixations demonstrate superior long-term implant survival

In our analysis, the 10-year unadjusted implant survival probability, with the endpoint being the first-time revision due to septic or aseptic stem loosening, was markedly superior in cemented primary stems as opposed to uncemented ones. Specifically, cemented stems exhibited a survival probability of 0.6 (95%-Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.45–0.68), compared to 0.4 (95%-CI: 0.30–0.44) for uncemented stems, as shown in Fig. 5 (p < .022).

Furthermore, during the initial nine years following primary implantation, the adjusted risk of first-time revision for septic or aseptic loosening was observed to be greater in uncemented stems, though with overlapping confidence intervals. After nine years following implantation, the adjusted survival probability of cemented stems tends to be higher compared to that of uncemented stems.

Kaplan Meier (KM) curves (95% CI) and Log-rank test for survival rate of the stem over grouped factors. The KM survival curves for each grouped factor were identified by colour and pattern differences.

Our data indicates a different risk profile for uncemented versus cemented stem designs in aseptic/septic stem revisions after primary implantation. Uncemented stems show a lower risk of first-time revision within the first year post-implantation, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.8 and a 95%-confidence interval (95%-CI) of 0.3 to 2.0, as seen in Table 5. However, from the second to the tenth year post-implantation, uncemented stems have a higher risk of first-time revision. This period sees a 1.2 times increased risk compared to cemented stems, with an HR of 1.2 and a 95%-CI of 0.7–1.8.

The Cox regression was adjusted for age, sex, and femoral bone defect size (aggregating defects into 3 main groups along Paprosky classes 1 + 2, 3a, 3b + 4). Cox-regression hazards ratio (HR) in multivariate analysis for predicting time to first-time revision due to aseptic stem loosening.

Discussion

The optimal fixation method for primary total hip arthroplasty—cemented or uncemented—continues to be a subject of clinical debate [30]. In our patient cohort, cemented stems were associated with a 32.39% incidence of significant bone defects (types 3b and 4) at the time of first revision. In contrast, such defects were observed in only 2.72% of cases with uncemented stems. When considering minor bone defects (types 1 and 2), uncemented stems were predominant, accounting for 82.07% in comparison to 47.89% for cemented stems. Moreover, a 17.30% greater occurrence of septic loosening was noted with cemented stems relative to their uncemented equivalents (28.17% vs. 10.87%, p < .001).

This observation aligns with findings from Tyson et al., who reported similar patterns of bone defect size in a registry study involving aseptic loosening after initial revision with uncemented/cememted fixation [22]. Gromov et al. also corroborated the trend of more severe bone defects being associated with cemented femoral components at re-revision [31]. Contrasting with the findings of Tyson et al. and Gromov et al., our investigation assessed femoral bone defects prior to the first revision and discerned that larger defects were also present with cemented stems. The literature suggests that for patients presenting with extensive bone defects and porous or osteoporotic bone, revision arthroplasties tend to be cemented or diaphyseally fixed to provide stable fixation across the defect site [32, 33]. Conversely, for those with robust bone quality and minor defects, an uncemented press-fit approach is favored to facilitate the biological integration of the implant through bone ongrowth [34]. Our study further substantiates this practice, indicating that patients initially receiving cemented stems typically underwent cemented or distally fixed revisions, implying the presence of larger bone defects [35, 36]. This finding raises particular concern for younger patients who are more likely to undergo future revisions; hence, the preservation of bone stock and the utilization of bone-sparing techniques are of the utmost importance. However, the selection of implants for initial revision procedures depends not only on the type of primary fixation, but also on a variety of other factors. These include the extent of the bone defect, the quality of the patient’s bone, the patient’s age, and their level of physical activity or lifestyle demands [31]. Additionally, the patient’s overall health status, the presence of any comorbidities, and the stability of the surrounding soft tissue structures play crucial roles in the decision-making process [37,38,39]. In the context of our study, the evaluation of osteoporosis prevalence at the time of primary implantation revealed no significant differences between the primary cemented and uncemented stem fixation groups within our cohort. This finding is crucial as it highlights the nuanced considerations required in choosing the appropriate stem fixation method. Moreover, the dominance of coxa norma in both cemented and uncemented groups underscores the commonality of hip geometry across different fixation types. Additionally, the prevalence of Dorr Type B among patients, irrespective of the stem fixation method, points to a predominant bone quality pattern in our cohort. These observations provide valuable insights into the factors influencing the choice of stem fixation and its potential impact on surgical outcomes, suggesting that both cemented and uncemented stems can be suitable for a wide range of bone qualities and hip geometries, contingent upon careful preoperative evaluation. Reflecting on the bone quality and shape of the proximal femur, as well as the angular relationships between the neck and shaft of the femur, which influence the biomechanics and loading of the hip joints, it was observed that these characteristics were approximately equally distributed at the time of primary implantation across both patient groups (cemented and uncemented stem fixation). This distribution suggests that the larger bone defects observed in our cohort may be more attributable to the use of cemented stem fixation. Furthermore, the surgeon must consider the likelihood of future revisions, the ease of implantation, and the expected longevity of the implant based on the patient’s life expectancy. These considerations ensure that the chosen implant best suits the individual needs and circumstances of each patient.

Cemented hip stems utilize Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bone cement to secure the prosthesis stem within the bone. Over time, potential loosening of this cement can lead to implant instability and the enlargement of bone defects [20, 40]. Bone cement may also provoke a biological response where the body attempts to resorb or bypass the material, exacerbating bone loss [40, 41]. Furthermore, cement degradation and the consequent peri-implant osteolysis due to the immunogenic reaction to cement particles can precipitate aseptic inflammation, further compromising peri-implant bone integrity [42,43,44].

In their analytical study, Gromov et al. reported a predominance of “aseptic stem loosening” as a revision cause, attributing 74% to cemented stems as opposed to 25% [31]. Diverging from Gromov’s findings, our data indicated a 28% elevated rate of aseptic loosening in uncemented stems and a 17.3% increased incidence of septic loosening in cemented stems. Uncemented stems rely on bone growth into the implant for stability, and this process can be affected by the mechanical stresses from physical activities [45]. Over time, these stresses might lead to micro-movements between the bone and the implant, potentially causing aseptic loosening [46, 47]. Conversely, the loosening rate in cemented stems could be linked to the inherent properties of cement, which may deteriorate or become unstable over time, thereby escalating infection risks. Within our patient population, the incidence of septic loosening in cemented stems was notable, comprising 17.3% of cases, suggesting an association between cementation and heightened infection susceptibility. The study “Two-stage revision for periprosthetic joint infection in cemented total hip arthroplasty: an increased risk for failure?” suggests that patients undergoing removal of cemented THA had higher rates of reinfection (22% compared to 7%, p = .021) and all-cause revision (31% compared to 14%, p = .039) than those with cementless THA [48]. This indicates a potential association between cementation and increased susceptibility to infection.

Cement’s propensity to ensnare bacteria and provide a conducive environment for bacterial colonization poses a significant risk, particularly if pathogenic organisms persist in the cement post-revision surgery, potentially leading to subsequent infections [49,50,51]. Therefore, in septic revision scenarios, cement avoidance is commonly advocated to enhance infection management [52, 53]. Moreover, our study unveiled an estimated Hazard Ratio for first-time revision that was 0.2 times lower for uncemented stems compared to cemented ones within the initial year post-implantation. However, in the span between the second and tenth years, the risk for first-time revision was observed to be 1.2 times higher for uncemented stems. This aligns with Tyson et al.‘s findings, which identified lower ten year implant survival rates associated with uncemented stems when factoring in re-revision for any cause [22].

While the retrospective nature of our study limits the availability of detailed primary surgery data, it uniquely explores the relationship between fixation techniques and femoral bone defect size, revision probability, and implant longevity in both aseptic and septic stem loosening cases. This is the first study to compare fixation effects on femoral bone defect size, revision risk, and implant longevity in aseptically and septically loosened stems following primary THA.

Our findings underscore the complexity of choosing between cemented and uncemented stems, highlighting that this decision should not be based solely on the fixation method but must consider a myriad of factors including the patient’s age, bone quality, activity level, and comorbid conditions. Our investigation indicates that uncemented stems are linked with a higher occurrence of minor bone defects and aseptic loosening. In contrast, it has been observed that cemented stems are associated with larger bone defects and an increased risk of septic loosening. This suggests that each fixation method has its unique advantages and limitations, which must be carefully weighed against the patient’s specific clinical context. Furthermore, the study highlights the need for continued research and development in implant technology, particularly in addressing the challenges associated with cement degradation and the risk of infection in cemented stems. In the end, the decision on the type of fixation should be tailored to each patient’s individual needs, taking into account their overall health, bone condition, and lifestyle.

Conclusion

This study concludes that cemented primary stems are associated with more extensive femoral bone defects at first-time revision and a higher incidence of septic loosening compared to uncemented stems. This differential in outcomes highlights the importance of individualized patient evaluation in choosing the appropriate fixation method for primary THA.

References

Swarup I, Lee YY, Chiu YF, Sutherland R, Shields M, Figgie MP (2018) Implant Survival and patient-reported outcomes after total hip arthroplasty in Young patients. J Arthroplasty 33(9):2893–2898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.04.016

Kelly MP, Chan PH, Prentice HA, Paxton EW, Hinman AD, Khatod M (2022) Cause-specific stem revision risk in primary total hip arthroplasty using cemented vs cementless femoral stem fixation in a US Cohort. J Arthroplasty 37(1):89–96e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.09.020

Feng X, Gu J, Zhou Y (2022) Primary total hip arthroplasty failure: aseptic loosening remains the most common cause of revision. Am J Transl Res 14(10):7080–7089

Hodges NA, Sussman EM, Stegemann JP (2021) Aseptic and septic prosthetic joint loosening: impact of biomaterial wear on immune cell function, inflammation, and infection. Biomaterials 278:121127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121127

Xie Y, Peng Y, Fu G, Jin J, Wang S, Li M, Zheng Q, Lyu FJ, Deng Z, Ma Y (2023) Nano wear particles and the periprosthetic microenvironment in aseptic loosening induced osteolysis following joint arthroplasty. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 13:1275086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1275086

Panez-Toro I, Heymann D, Gouin F, Amiaud J, Heymann MF, Córdova LA (2023) Roles of inflammatory cell infiltrate in periprosthetic osteolysis. Front Immunol 14:1310262. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1310262

Yin Z, Gong G, Liu X, Yin J (2023) Mechanism of regulating macrophages/osteoclasts in attenuating wear particle-induced aseptic osteolysis. Front Immunol 14:1274679. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1274679

Xie J, Hu Y, Li H, Wang Y, Fan X, Lu W, Liao R, Wang H, Cheng Y, Yang Y, Wang J, Liang S, Ma T, Su W (2023) Targeted therapy for peri-prosthetic osteolysis using macrophage membrane-encapsulated human urine-derived stem cell extracellular vesicles. Acta Biomater 160:297–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2023.02.003

Morawietz L, Classen RA, Schröder JH, Dynybil C, Perka C, Skwara A, Neidel J, Gehrke T, Frommelt L, Hansen T, Otto M, Barden B, Aigner T, Stiehl P, Schubert T, Meyer-Scholten C, König A, Ströbel P, Rader CP, Kirschner S, Lintner F, Rüther W, Bos I, Hendrich C, Kriegsmann J, Krenn V (2006) Proposal for a histopathological consensus classification of the periprosthetic interface membrane. J Clin Pathol 59(6):591–597. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2005.027458

Zeng ZJ, Yao FM, He W, Wei QS, He MC (2023) Incidence of periprosthetic joint infection after primary total hip arthroplasty is underestimated: a synthesis of meta-analysis and bibliometric analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 18(1):610. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-04060-5

Kurtz SM, Lau EC, Son MS, Chang ET, Zimmerli W, Parvizi J (2018) Are we winning or losing the Battle with Periprosthetic Joint infection: Trends in Periprosthetic Joint Infection and mortality risk for the Medicare Population. J Arthroplasty 33(10):3238–3245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.05.042

Lenguerrand E, Whitehouse MR, Beswick AD, Jones SA, Porter ML, Blom AW (2017) Revision for prosthetic joint infection following hip arthroplasty: evidence from the National Joint Registry. Bone Joint Res 6(6):391–398. https://doi.org/10.1302/2046-3758.66.BJR-2017-0003.R1

Dale H, Høvding P, Tveit SM, Graff JB, Lutro O, Schrama JC, Wik TS, Skråmm I, Westberg M, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O (2021) Increasing but levelling out risk of revision due to infection after total hip arthroplasty: a study on 108,854 primary THAs in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register from 2005 to 2019. Acta Orthop 92(2):208–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2020.1851533

Chang CH, Lee SH, Lin YC, Wang YC, Chang CJ, Hsieh PH (2020) Increased periprosthetic hip and knee infection projected from 2014 to 2035 in Taiwan. J Infect Public Health 13(11):1768–1773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.04.014

Li C, Renz N, Trampuz A, Ojeda-Thies C (2020) Twenty common errors in the diagnosis and treatment of periprosthetic joint infection. Int Orthop 44(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-019-04426-7

McMaster Arthroplasty Collaborative (MAC) (2020) Risk factors for Periprosthetic Joint Infection Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: a 15-Year, Population-based Cohort Study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102(6):503–509. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.19.00537

Bandick E, Biedermann L, Ren Y, Donner S, Thiele M, Korus G, Tsitsilonis S, Müller M, Duda G, Perka C, Kienzle A (2023) Periprosthetic Joint Infections of the knee lastingly Impact the bone homeostasis. J Bone Min Res 38(10):1472–1479. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4892

Oliveira TC, Gomes MS, Gomes AC (2020) The Crossroads between Infection and Bone Loss. Microorganisms 8(11):1765. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8111765

Hasandoost L, Rodriguez O, Alhalawani A, Zalzal P, Schemitsch EH, Waldman SD, Papini M, Towler MR (2020) The role of poly(Methyl Methacrylate) in management of bone loss and infection in revision total knee arthroplasty: a review. J Funct Biomater 11(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb11020025

Vaishya R, Chauhan M, Vaish A (2013) Bone cement. J Clin Orthop Trauma 4(4):157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2013.11.005

Willert HG, Bertram H, Buchhorn GH (1990) Osteolysis in alloarthroplasty of the hip. The role of bone cement fragmentation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 258:108–121

Tyson Y, Hillman C, Majenburg N, Sköldenberg O, Rolfson O, Kärrholm J, Mohaddes M, Hailer NP (2021) Uncemented or cemented stems in first-time revision total hip replacement? An observational study of 867 patients including assessment of femoral bone defect size. Acta Orthop 92(2):143–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2020.1846956

Kiran M, Johnston LR, Sripada S, Mcleod GG, Jariwala AC (2018) Cemented total hip replacement in patients under 55 years. Acta Orthop 89(2):152–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1427320

Blankstein M, Lentine B, Nelms NJ (2020) The Use of Cement in Hip Arthroplasty: a contemporary perspective. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28(14):e586–e594. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00604

Mäkelä KT, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, Virolainen P, Paavolainen P, Remes V (2011) Cemented versus cementless total hip replacements in patients fifty-five years of age or older with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(2):178–186. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.I.01283

Peitgen DS, Innmann MM, Merle C, Gotterbarm T, Moradi B, Streit MR (2018) Periprosthetic bone Mineral Density around Uncemented Titanium stems in the second and third Decade after total hip arthroplasty: a DXA Study after 12, 17 and 21 years. Calcif Tissue Int 103(4):372–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-018-0438-9

Karia M, Logishetty K, Johal H, Edwards TC, Cobb JP (2023) 5 year follow up of a hydroxyapatite coated short stem femoral component for hip arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Sci Rep 13(1):17166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44191-7

McNally M, Sousa R, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, Chen AF, Soriano A, Vogely HC, Clauss M, Higuera CA, Trebše R (2021) The EBJIS definition of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J 103–B(1):18–25. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.103B1.BJJ-2020-1381.R1

Ibrahim DA, Fernando ND (2027) Classifications in brief: the Paprosky classification of femoral bone loss. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475(3):917–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5012-z

Konan S, Abdel MP, Haddad FS (2020) Cemented versus uncemented hip implant fixation: should there be age thresholds? Bone Joint Res 8(12):604–607. https://doi.org/10.1302/2046-3758.812.BJR-2019-0337

Gromov K, Pedersen AB, Overgaard S, Gebuhr P, Malchau H, Troelsen A (2015) Do Rerevision Rates Differ after First-time revision of primary THA with a cemented and cementless femoral component? Clin Orthop Relat Res 473(11):3391–3398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4245-6

Ding Z, Ling T, Mou P, Wang D, Zhou K, Zhou Z (2020) Bone restoration after revision hip arthroplasty with femoral bone defects using extensively porous-coated stems with cortical strut allografts. J Orthop Surg Res 15(1):194. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-020-01720-8

Wirtz DC, Gravius S, Ascherl R, Thorweihe M, Forst R, Noeth U, Maus UM, Wimmer MD, Zeiler G, Deml MC (2014) Uncemented femoral revision arthroplasty using a modular tapered, fluted titanium stem: 5- to 16-year results of 163 cases. Acta Orthop 85(6):562–569. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453674.2014.958809

Park KS, Jin SY, Lim JH, Yoon TR (2021) Long-term outcomes of cementless femoral stem revision with the Wagner cone prosthesis. J Orthop Surg Res 16(1):375. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-021-02457-8

Cnudde PH, Kärrholm J, Rolfson O, Timperley AJ, Mohaddes M (2017) Cement-in-cement revision of the femoral stem: analysis of 1179 first-time revisions in the Swedish hip Arthroplasty Register. Bone Joint J 99-B(4 Supple B):27–32. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B4.BJJ-2016-1222.R1

Malahias MA, Mancino F, Agarwal A, Roumeliotis L, Gu A, Gkiatas I, Togninalli D, Nikolaou VS, Alexiades MM (2021) Cement-in-cement technique of the femoral component in aseptic total hip arthroplasty revision: a systematic review of the contemporary literature. J Orthop 26:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.06.002

Pflüger MJ, Frömel DE, Meurer A (2021) Total hip arthroplasty revision surgery: impact of morbidity on Perioperative outcomes. J Arthroplasty 36(2):676–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.08.005

Khatod M, Cafri G, Inacio MC, Schepps AL, Paxton EW, Bini SA (2015) Revision total hip arthoplasty: factors associated with re-revision surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 97(5):359–366. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.N.00073

Lakomkin N, Goz V, Lajam CM, Iorio R, Bosco JA 3rd (2017) Higher modified Charlson Index scores are Associated with increased incidence of complications, transfusion events, and length of Stay following revision hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 32(4):1121–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.014

Wang Y, Shen S, Hu T, Williams GR, Bian Y, Feng B, Liang R, Weng X (2021) Layered double hydroxide modified bone cement promoting osseointegration via Multiple Osteogenic Signal Pathways. ACS Nano 15(6):9732–9745. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c00461

Couto M, Vasconcelos DP, Sousa DM, Sousa B, Conceicao F, Neto E, Lamghari M, Alves CJ (2020) The mechanisms underlying the Biological response to wear debris in Periprosthetic inflammation. Front Mater 7:274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2020.00274

Mahon OR, O’Hanlon S, Cunningham CC, McCarthy GM, Hobbs C, Nicolosi V, Kelly DJ, Dunne A (2018) Orthopaedic implant materials drive M1 macrophage polarization in a spleen tyrosine kinase- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent manner. Acta Biomater 65:426–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2017.10.041

Jiang J, Jia T, Gong W, Ning B, Wooley PH, Yang SY (2016) Macrophage polarization in IL-10 treatment of Particle-Induced inflammation and Osteolysis. Am J Pathol 186(1):57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.09.006

Goodman SB, Gallo J (2019) Periprosthetic Osteolysis: mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment. J Clin Med 8(12):2091. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8122091

Kheir MM, Drayer NJ, Chen AF (2020) An update on Cementless femoral fixation in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 102(18):1646–1661. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.19.01397

Kohli N, Stoddart JC, van Arkel RJ (2021) The limit of tolerable micromotion for implant osseointegration: a systematic review. Sci Rep 11(1):10797. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90142-5

Hartmann ES, Köhler MI, Huber F, Redeker JI, Schmitt B, Schmitt-Sody M, Summer B, Fottner A, Jansson V, Mayer-Wagner S (2017) Factors regulating bone remodeling processes in aseptic implant loosening. J Orthop Res 35(2):248–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23274

Hipfl C, Leopold V, Becker L, Pumberger M, Perka C, Hardt S (2023) Two-stage revision for periprosthetic joint infection in cemented total hip arthroplasty: an increased risk for failure? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 143(7):4481–4490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-022-04671-3

McConoughey SJ, Howlin RP, Wiseman J, Stoodley P, Calhoun JH (2015) Comparing PMMA and calcium sulfate as carriers for the local delivery of antibiotics to infected surgical sites. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 103(4):870–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.33247

Bistolfi A, Ferracini R, Albanese C, Vernè E, Miola M (2019) PMMA-Based bone cements and the Problem of Joint Arthroplasty infections: Status and New perspectives. Mater (Basel) 12(23):4002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12234002

Mu W, Ji B, Cao L (2023) Single-stage revision for chronic periprosthetic joint infection after knee and hip arthroplasties: indications and treatments. Arthroplasty 5(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42836-023-00168-5

Mangin M, Aouzal Z, Leclerc G, Sergent AP, Bouiller K, Patry I, Garbuio P (2023) One-stage revision hip arthroplasty for infection using primary cementless stems as first-line implants: about 35 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 109(7):103642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2023.103642

Born P, Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Zwicky L, Graber P, Ochsner PE, Clauss M (2016) Eradication of infection, survival, and radiological results of uncemented revision stems in infected total hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 87(6):637–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1237423

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. There was no external source of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W., M.P., S.H.; methodology, N.W.; S.H.; software, N.W., S.H.; validation, N.W., M.P.; S.H.; formal analysis, N.W.; M.P.; S.H.; investigation, N.W.; M.P.; S.H.; resources, M.P.; data curation, N.W.; M.P. and S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W.; writing—review and editing, N.W.; M.P. and S.H.; visualization, N.W.; S.H.; supervision, N.W.; M.P.; S.H.; project administration, N.W.; M.P.; S.H.; funding acquisition, M.P.; S.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, with the ethical consent number EA4/129/23.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images Fig. 1a-c.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wagener, N., Pumberger, M. & Hardt, S. Impact of fixation method on femoral bone loss: a retrospective evaluation of stem loosening in first-time revision total hip arthroplasty among two hundred and fifty five patients. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-024-06230-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-024-06230-4