Abstract

Purpose

Deformation of the talus in idiopathic congenital clubfeet is a known problem after treatment. However evidence on types of talus deformation and clinical relevance is rare. The aims of this study were first to define different types of talus deformation, and second, to evaluate the impact of these types on long-term results.

Methods

At a minimum follow-up of ten years 40 idiopathic clubfeet treated by a modified dorsomedial release were analyzed. Based on morphological appearance and the widened range of radius to length ratios (R/L-ratio) in treated clubfeet deformed tali were divided into two groups: tali with decreased R/L-ratios were classified as small-dome talus deformation (SD), tali with increased R/L-ratios were classified as flat-top talus deformation (FT). The impact on degree of arthrosis in the ankle joint, clinical outcome, and ankle range of motion was analyzed.

Results

Small-dome talus deformation (SD) was found in nine feet. This group showed decreased R/L-ratios and increased talus opening angles, which were linked to an increased range of motion of the ankle joint (p = 0.033). The impact on onset of arthrosis was not significant for this group (p = 0.056). The group of flat top talus deformation (nine feet) showed increased R/L-ratios and decreased talus opening angles, decreased range of motion (p = 0.019), and a significant impact on onset of arthrosis (p = 0.010).

Conclusion

Our study defines a new subgroup of talus deformation: the small dome talus deformation tends to show a better ankle joint range of motion and a lower risk of arthrosis compared to the classical flat dome talus deformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic congenital clubfoot (ICF) is a complex and relatively common deformity with a prevalence of between 0.6 and 6.8 per 1000 births [1]. The complexity of the deformity is based on the combination of equinus, hindfoot-varus, forefoot-adductus, and cavus deformity of the foot. Additionally clubfoot deformity varies in terms of severity and stiffness [2, 12]. While the cause of idiopathic clubfoot deformity remains unknown, pathologic abnormalities of muscles, soft tissues, nerve abnormalities, and vascular anomalies have been reported [3]. Moreover an association to other congenital disorders like developmental dysplasia of the hip has been controversially discussed among the literature [4–6].

Treatment modalities for clubfoot deformity include surgical and nonsurgical strategies. In the past decades non-operative treatment modalities have gained increasing acceptance as the treatment modality of choice. Especially the introduction and broad acceptance of the Ponseti technique [7, 8], the Kite and Lovell [9] technique, and the French approach [10] have led to a decreasing number of cases treated surgically. Surgical treatment of idiopathic clubfoot deformity has also evolved over time: an approach using pre-operative treatment to reduce the need for extensive surgery has gained increasing acceptance [11]. The common goal of all treatment modalities for clubfoot deformities is to achieve full and lasting correction and optimal function of the foot: good clinical results of surgical as well as conservative treatment modalities of idiopathic clubfeet have been reported [12–16].

However, despite the central role of the talus bone there are only a few reports dealing with talus deformities in clubfeet among the literature [17]: nevertheless talar flattening and distortion were reported after correction using a posteromedial release [18] and Ponseti treatment [14]. Furthermore reports show that flattening of the talus compromises the dynamic ankle mobility [18, 19]. Concerning differing patterns of talus deformation following clubfoot treatment there is very little evidence [20]. But the question remains: Is there just one type of talus deformation following treatment of idiopathic clubfoot?

The aims of this study were first to define different types of talus deformation and second to evaluate the impact of the different deformation patterns on long-term results of idiopathic clubfoot correction.

Material and methods

This retrospective analytical study was conducted at a single tertiary care institution (level of evidence III). Medical records of patients with clubfoot deformity treated surgically between 1993 and 2002 at our institution were reviewed, revealing 28 consecutive patients (40 clubfeet) meeting the inclusion criteria. All patients were contacted for a standardized follow-up examination.

Surgical treatment was performed as modified “a la carte” dorsomedial release in all cases [11]: prior to surgical correction all feet were treated by serial casting in order to reduce the need for extensive surgery. Clubfoot deformity was bilateral in 12 of the 28 patients. Of the patients 21.4 % were female, 78.6 % were male. Mean age at time of surgical treatment was 5.6 month (range 3.5 to 15.1). The minimum follow-up was ten years.

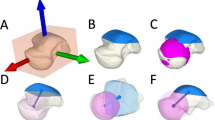

At time of follow-up standard radiographs were taken of all feet. An anteroposterior (AP) view [14] and a true lateral view of the ankle (Lat) were obtained [20]. Analysis of the radiographs was performed with a special focus on the talus shape: flattening of the talus dome was classified according to the criteria published by Dunn [20] (0 = normal, 1 = mildly flattened, 2 = moderately flattened, 3 = severely flattened). The radius to length-ratio (R/L-ratio), an index of talar flattening, was calculated by measuring the radius of curvature of the talar dome using Mose rings, and the length of the talus from its posterior extremity to the talar head [19, 21]. The opening angle of the talus dome (alpha-angle) from the anterior to the posterior trochlea end was measured in the lateral plane (see Fig. 1).

Based on morphological appearance and R/L-ratios treated feet were divided, by consensus of two orthopedic surgeons, into three groups according to the talus shape: tali with reduced R/L-ratios were classified in the group of small dome talus deformation. According to the criteria published by Dunn [20] tali with increased R/L-ratios were classified in the group of flattop talus deformation, and feet with normal shaped tali were classified in the group of normal shaped tali (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Based on R/L-ratios of the contralateral healthy feet and on the morphological appearance of the treated tali R/L-ratios below 0.33 were considered as small dome, whereas R/L-ratios above this limit were considered as normal or increased. According to Dunn [20] the classification of the flattop talus deformation is based on the morphologic appearance showing flattening and incongruity of the talus bone. This classification is not primarily based on R/L-ratios. Thus, the group of flattop talus deformation shows increased R/L-ratios, but there is no specific limit defined.

Radiographic signs of osteoarthrosis in the ankle joint were assessed according to criteria established by Kellgren and Lawrence [22] (0 = none, 1 = doubtful, 2 = minimal, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe).

All measurements were made using the Impax EE r20 xv software (Agfa Health Care N.V., Belgium).

A standardized physical examination was performed in all patients. The Functional Rating System for Clubfoot Surgery (FRSCS) and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) 10-point activity scale were used to measure the clinic outcome [3, 23].

Institutional review board approval was obtained for the retrospective evaluation at our institution. All patients or legal guardians gave their informed consent prior to the inclusion in this study.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described by mean (± standard deviation), the UCLA score by median (quartiles), and categorical variables by percentages. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) models were performed to compare continuous variables between different types of talus deformation accounting for the patient effect as a random block factor. Pairwise comparisons were adjusted using the Tukey-Kramer method. The Kellgren-Lawrence score and the UCLA score were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test, pairwise comparisons were done using the Wilcoxon rank sum test applying the closed testing principle. With respect to the UCLA score patient-based measurements were used and compared between the following 3 groups: 1) patients with at least one flattop talus; 2) patients with at least one small dome talus; 3) patients without any flattop or small dome talus. All p-values are results of two-sided tests and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normal distribution and Pearson’s correlation was used to analyze the relation of defined parameters.

Statistical analyses were performed using the software SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. 2002–2012; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Radiological analysis and clinical examination were performed in all patients at a mean follow-up time of 15.4 years (range 10.1 to 20.9).

The talus shape was judged to be normal in 56 % of the treated feet. In the group of treated clubfeet the mean R/L-ratio was 0.41 (range 0.23 to 0.71) compared to a mean of 0.40 (range 0.35 to 0.44) in the control group (Fig. 2). Moderate to severe deformation of the talus was seen in 44 % of the treated feet: small dome deformation of the talus was found in nine feet (22 %). Moderate to severe flat top talus deformation was found in 22 % (nine feet) of the cohort according to the classification suggested by Dunn et al. [20]. In contrast to the small dome talus group this group showed increased R/L-ratios. R/L-ratios of the different talus deformity groups are given in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Follow-up time showed no significant difference between the small-dome talus group and the flat-top talus group (p = 0.161). In all healthy contralateral feet (control group) tali were judged to be shaped normally.

Arthrosis of the ankle joint was judged to be grade one (doubtful) in 41.5 %, and grade two (minimal) in 26.8 % according to Kellgren and Lawrence [22]. Moderate or severe arthrosis was not seen in our cohort. Of the treated feet 31.7 % showed no sign of arthrosis at time of follow-up. Degree of arthrosis of the different talus deformity groups are given in Fig. 3.

Mean values of ankle range of motion, alpha angles, FRSCS, and Kellgren and Lawrence-grading of all talus groups and p-values of the comparison between each group are given in Table 2.

We found a significant difference between the small talus dome group and the flattop talus group for the alpha angle (p < 0.001) and a non-significant difference of the ankle range of motion (see Figs. 4 and 5). We found a moderate positive correlation between the ankle range of motion and the clinical outcome measured by FRSCS score (r = 0.43, p = 0.005), and a weak positive correlation between the alpha angle and the ankle range of motion (r = 0.33, p = 0.033).

Talus opening angles (alpha angles, see Fig. 1) of all treated clubfeet, controls, and the treated talus groups: small-dome, flat-top, and normal shaped tali

We found a significant difference of the grade of arthrosis between the group with normal shaped tali and the flattop talus group (p = 0.010) and a non-significant difference between the group with normal shaped tali and the small talus group (p = 0.056). The difference of the arthrosis scores between the small talus group and the flattop talus group was not significant (p = 0.514).

The statistical analysis revealed a significant difference of the FRSCS between the group with normal shaped tali and the small dome talus group (p = 0.040) and between the group with normal shaped tali and the flat top talus group (p = 0.020). The difference of the FRSCS between the small dome talus group and the flattop talus group was not significant (p = 0.941) (see Fig. 6).

Considering the UCLA score we compared the following three groups of patients: 1) patients with at least one flattop talus; 2) patients with at least one small dome talus; 3) patients without any flattop or small dome talus; no statistically significant difference was found between patient groups with respect to the UCLA score, with median (quartile) values of 8.0 (7.0–9.0) in group 1, 8.5 (6.0–9.0) in group 2 and 9.0 (8.0 – 9.0) in group 3 (p = 0.512).

A comparison of treatment parameters in the small dome talus and the flat top talus group is shown in Table 3. The differences between the two groups were not significant.

Discussion

In the long history of treatment of idiopathic congenital clubfoot various radiological parameters have been suggested to measure the effectiveness of treatment strategies [1]. However reports on results of clubfoot treatment are often based on clinical scores or mailed questionnaires and radiological analysis, if performed, is limited to the assessment of arthrosis in the majority of cases (see Table 4). Deformation of the talus has been described as a central parameter [20], but detailed analysis of talar deformations in idiopathic clubfeet is rarely reported.

The purpose of this study was first to define different types of talus deformation based on radiographic analysis:

Our data demonstrate that R/L-ratios in treated clubfeet show a wider range than in healthy contralateral feet (Fig. 2). This finding is supported by Bach et al. who reported a wide range for the R/L-ratio in patients who underwent Turco’s posteromedial release because of idiopathic clubfeet [19]. In contrast, similar to our findings in healthy contralateral feet Hjelmstedt at al. reported a smaller range for the R/L-ratio of 0.365 with a standard deviation of 0.045 in normal feet [21]. The measurement of R/L-ratios has proven reliable [19] and it delivers additional information to the classification published by Dunn [20]. The section of increased R/L-ratios represents tali with the former reported flattop talus deformation [15, 19, 20].

In contrast, our data also show a group of treated feet with decreased R/L-ratios. This suggests that there is a group with deformed tali showing decreased R/L-ratios representing the described small dome talus deformation (Fig. 1).

The talus and its shape are essential key features of the effective clubfoot treatment. The talus shape not only determines the ankle movement [19] but it is also a central predictive factor for the onset of ankle arthrosis [17]. Thus, it seems important to analyze not only ankle arthrosis, but also the different types of talus deformation in the clubfoot follow-up which also creates some future prospects for the patients. This insight cannot be given based on clinical measurements only.

In the second part of this study, we evaluated the impact of the different deformation patterns on long-term results of idiopathic clubfoot correction:

The overall long term results shown in this study were satisfying in most cases: functional excellent or good results were seen in 65 %. Besides recurrence of deformation arthrosis is most likely to affect function in the following decades. Reports showed that in the long run arthrosis is more common in treated clubfeet than in contralateral normal feet [13].

In our cohort initial signs of arthrosis were seen quite frequently in cases with flattop talus deformation, but not that frequent in the small dome talus group. Thus, the difference between the flat top talus group and the group of normal shaped tali was significant (p = 0.010, see Table 2). Whereas the difference between the small dome talus group and the normal shaped talus group was not significant (p = 0.056).

The small dome talus group shows significant increased alpha angles compared to the flat top talus group. Our data show a trend of better ankle range of motion for the small dome talus group compared to the flat top talus group. Thus, the difference of ankle range of motion between the group of normal shaped tali and flat top tali was significant, whereas the difference between the normal shaped talus group and the small dome talus group was not significant (Table 2). These findings are coherent with the report of Bach et al., who described a decreased dynamic range of ankle motion in feet with talar flattening [18].

We did not see a significant difference of the clinical results measured by FRSCS between the small dome talus group and the flat top talus group, but there is a trend to better results in the small dome talus group.

Talus deformation was mainly reported following surgical treatment of clubfoot deformity [24], but there are also reports on talus deformation following Ponseti treatment [14]. Therefore, we believe that the analysis of the talus shape is also important for these treatment modalities.

One question that remains is whether talus deformation is a result of the applied pressure during the correction process or due to the initial surgical correction. In addition it is unclear which circumstances determine the type of talus deformation. However, in case of talus deformation our data show a non-significant trend that the a shorter postoperative casting time, the release of the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus tendon, and a shorter time of pin trans-fixation favors the development of the small dome deformation. Further research is needed to analyze factors causing and determining the different talus deformation types in idiopathic clubfeet undergoing treatment.

Conclusion

Our study shows that there are different subgroups of talus deformation: the small dome talus deformation tends to show a better ankle joint range of motion and a lower risk of arthrosis compared to the classical flat dome talus deformation.

Limitations

Limitations to this study are the retrospective design and the limited cohort size within the talus deformity subgroups.

References

Barker S, Chesney D, Miedzybrodzka Z, Maffulli N (2003) Genetics and epidemiology of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus. J Pediatr Orthop 23:265–72

Lampasi M, Trisolino G, Abati CN et al (2016) Evolution of clubfoot deformity and muscle abnormality in the Ponseti method: evaluation with the Dimeglio score. Int Orthop. doi:10.1007/s00264-016-3244-x

Cummings RJ, Davidson RS, Armstrong PF, Lehman WB (2002) Congenital clubfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84–A:290–308

Perry DC, Tawfiq SM, Roche A et al (2010) The association between clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br Vol 92:1586–1588. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.92B11.24719

Ibrahim T, Riaz M, Hegazy A (2015) The prevalence of developmental dysplasia of the hip in idiopathic clubfoot: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop 39:1371–8. doi:10.1007/s00264-015-2757-z

Zhao D, Rao W, Zhao L et al (2013) Is it worthwhile to screen the hip in infants born with clubfeet? Int Orthop 37:2415–2420. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2073-4

Ponseti IV (2000) Clubfoot management. J Pediatr Orthop 20:699–700

van Wijck SFM, Oomen AM, van der Heide HJL (2015) Feasibility and barriers of treating clubfeet in four countries. Int Orthop 39:2415–2422. doi:10.1007/s00264-015-2783-x

Kite J (1964) THE CLUBFOOT. In: Grune Strat. New York. http://www.abebooks.de/CLUBFOOT-Kite-H-Grune-Stratton-New/1170157616/bd. Accessed 29 Sep 2014

Bensahel H, Guillaume A, Czukonyi Z, Desgrippes Y (1990) Results of physical therapy for idiopathic clubfoot: a long-term follow-up study. J Pediatr Orthop 10:189–92

Bensahel H, Csukonyi Z, Desgrippes Y, Chaumien JP (1987) Surgery in residual clubfoot: one-stage medioposterior release “à la carte”. J Pediatr Orthop 7:145–8

Hsu LP, Dias LS, Swaroop VT (2013) Long-term retrospective study of patients with idiopathic clubfoot treated with posterior medial-lateral release. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95:e27. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00246

van Gelder JH, van Ruiten AGP, Visser JD, Maathuis PGM (2010) Long-term results of the posteromedial release in the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop 30:700–4. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181ec9402

Laaveg SJ, Ponseti IV, Laaveg BYSJ et al (1980) Long-term results of treatment of congenital club foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am 62:23–31

Limpaphayom N, Kerr SJ, Prasongchin P (2014) Idiopathic clubfoot: ten year follow-up after a soft tissue release procedure. Int Orthop. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2526-4

Cooper DMM, Dietz FRM (1995) Treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. A thirty-year follow-up note. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 77:1477–89

Ponseti I V, El-Khoury GY, Ippolito E, Weinstein SL (1981) A radiographic study of skeletal deformities in treated clubfeet. Clin Orthop Relat Res 30–42

Bach CM, Wachter R, Stöckl B et al (2002) Significance of talar distortion for ankle mobility in idiopathic clubfoot. Clin Orthop Relat Res 196–202

Bach CM, Goebel G, Mayr E et al (2005) Assessment of talar flattening in adult idiopathic clubfoot. Foot Ankle Int 26:754–60

Dunn HK, Samuelson KM (1974) Flat-top talus. A long-term report of twenty club feet. J Bone Joint Surg Am 56:57–62

Hjelmstedt A, Sahlstedt B (1978) Simultaneous arthrography of the talocrural and talonavicular joints in children. IV. Measurements on congenital club feet. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 19:223–36

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS (1957) Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 16:494–502

Zahiri CA, Schmalzried TP, Szuszczewicz ES, Amstutz HC (1998) Assessing activity in joint replacement patients. J Arthroplasty 13:890–5

Dobbs MB, Gurnett CA (2009) Update on clubfoot: etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467:1146–53. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-0734-9

Radler C, Mindler GT, Riedl K, et al. (2013) Midterm results of the Ponseti method in the treatment of congenital clubfoot. Int Orthop 37:1827–31. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2029-8

Smith P a, Kuo KN, Graf AN, et al. (2014) Long-term results of comprehensive clubfoot release versus the Ponseti method: which is better? Clin Orthop Relat Res 472:1281–90. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3386-8

Dobbs MB, Nunley R, Schoenecker PL (2006) Long-term follow-up of patients with clubfeet treated with extensive soft-tissue release. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:986–996. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00114

Levin MN, Kuo KN, Harris GF, Matesi D V (1989) Posteromedial release for idiopathic talipes equinovarus. A long-term follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 265–8

Porecha MM, Parmar DS, Chavda HR (2011) Mid-term results of Ponseti method for the treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot--(a study of 67 clubfeet with mean five year follow-up). J Orthop Surg Res 6:3. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-6-3

Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Caterini R, Tudisco C (2003) Long-term comparative results in patients with congenital clubfoot treated with two different protocols.J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A:1286–94

Kalenderer O, Reisoglu A, Turgut A, Agus H (2008) Evaluation of clinical and radiographic outcomes of complete subtalar release in clubfoot treatment. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 98:451–6

Mahan ST, Spencer SA, Kasser JR (2014) Satisfactory patient-based outcomes after surgical treatment for idiopathic clubfoot: includes surgeon’s individualized technique. J Pediatr Orthop 34:631–8. doi:10.1097/BPO.0000000000000197

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna, Austria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolb, A., Willegger, M., Schuh, R. et al. The impact of different types of talus deformation after treatment of clubfeet. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 41, 93–99 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3301-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3301-5