Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in developed countries and atherosclerosis is the major cause of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerotic lesions obstruct blood flow in the arterial vessel wall and can rupture leading to the formation of occlusive thrombi. Conventional diagnostic tools are still of limited value for identifying the vulnerable arterial plaque and for predicting its risk of rupture and of releasing thromboembolic material. Knowledge of the molecular and biological processes implicated in the process of atherosclerosis will advance the development of imaging probes to differentiate the vulnerable plaque. The development of imaging probes with high sensitivity and specificity in identifying high-risk atherosclerotic vessel wall changes and plaques is crucial for improving knowledge-based decisions and tailored individual interventions. Arterial PET imaging with 18F-FDG has shown promising results in identifying inflammatory vessel wall changes in numerous studies and clinical trials. However, due to its limited specificity in general and its intense physiological uptake in the left ventricular myocardium that impair imaging of the coronary arteries, different PET tracers for the molecular imaging of atherosclerosis have been evaluated. This review describes biological, chemical and medical expertise supporting a translational approach that will enable the development of new or the evaluation of existing PET tracers for the identification of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques for better risk prediction and benefit to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vascular disease is still the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world, and the primary cause of myocardial infarction, stroke, and ischaemia. Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease of the large arteries that remains asymptomatic for decades. Arterial wall changes in the context of atherosclerosis start in childhood and vascular lesions enlarge with age and typically become symptomatic at 50–60 years of age. The pathobiology of atherosclerosis is complex and lesions can be generally divided into stable and unstable (also termed vulnerable) plaques. While stable plaques can occlude the lumen of the arterial vessel over time, they can develop plaque erosion. Moreover, plaque rupture is the dominant initiating event, responsible for 60–70% of acute coronary syndromes (ACS). It is therefore important to develop tools that discriminate between plaques that become vulnerable and plaques that remain stable but display erosion. State-of-the-art imaging using novel probes identifying molecular and cellular processes associated with plaque rupture have the potential for better patient stratification and personalized strategies.

Plaque biology: cellular and molecular mechanisms

The process of atherogenesis starts with activation of vascular endothelial cells, either by vascular shear stress [1] or local processes [2]. Also platelets can deposit so-called footprints that direct leucocytes to the vasculature [3]. At the same time as leucocyte infiltration, a heterogeneous population of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) is established in the subintimal space [4]. It has been shown that VSMCs are important in health and disease [5]. The pool of intimal VSMCs in the atherosclerotic lesion might arise from the infiltration of haematopoietic stem cells that differentiate locally into VSMCs [6]. However, more recently, VSMC lineage tracing in apoE-null mice has shown that a majority of atherosclerotic lesion cells are derived from VSMCs from the vasculature [7]. The accumulation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), that become oxidized, promotes macrophages to take up these remnants via their scavenger receptor. These foam cells are the starting point of the so-called fatty streak. In response to these proinflammatory macrophages, more VSMCs migrate into the vascular intima producing a fibrous cap around the xanthomal lesion. In addition, the proinflammatory macrophages attract more macrophages which further fuel the inflammatory vascular process. Due to hypoxia in the core of the atherosclerotic plaque, a necrotic core develops and intraplaque neovascularization is upregulated in response. Finally, cellular debris calcifies and the amount of calcification is a measure of the atherosclerotic burden [8].

Many features have been linked to plaque vulnerability including perivascular inflammation, large necrotic core, thin fibrous cap, microcalcifications, intraplaque haemorrhage, neoangiogenesis and hypoxia [9]. A thin fibrous cap is the result of degradation of collagen by metalloproteinase derived from activated macrophages. The rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque usually takes place at the shoulders of the plaque where the cap is thinnest. A large necrotic core and increased angiogenesis are a consequence of inflammation and hypoxia. Endothelial cells of intraplaque (micro)vessels express adhesion molecules favouring leucocyte recruitment. These angiogenic vessels are immature and fragile and due to extravasation of leucocytes further contribute to atherosclerosis progression. Inflammation has been linked to both apoptosis and calcification [10, 11], and oxidative stress has been shown to be responsible for VSMC calcification [12, 13].

Vascular calcification was long considered a passive process not amenable to intervention. A paradigm shift came with the discovery that so-called Gla proteins are involved in the regulation of mineral deposition in the vasculature [14]. Vascular calcification is now considered an active process with cellular and humoral contributions which plays an important role in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [15]. The discovery that vitamin K-dependent proteins are inhibitors of vascular calcification has advanced our mechanistic understanding of the calcification process and opened novel avenues for diagnosis and treatment [16].

Vascular calcification comes in different flavours: calcification can occur in the vascular intima as well as in the media and it may have different shapes and sizes. Recent data suggest that microcalcification can have a destabilizing effect on atherosclerotic plaques [2, 17], in contrast to the hypothesis that large calcifications are plaque-stabilizing. Microcalcification arises from dedifferentiated VSMCs that start secreting extracellular vesicles, that in the extracellular space form the nidus for calcification [18]. These microcalcifications, which are undetectable by conventional imaging, increase the local stress inside the thin fibrous cap twofold and thus increase the likelihood of rupture [19]. These microcalcifications will eventually result in macrocalcification as a product of osteogenic action by osteocyte-like and chondrocyte-like cells inside the plaque. Novel imaging tools allow the course of microcalcification to be followed [20]. In a rodent model of atherosclerosis, macrophage infiltration in early atherosclerotic plaques has been shown to colocalize with calcification. Indeed, microcalcifications that are phagocytosed by macrophages polarize towards the proinflammatory M1 phenotype [21].

Effective screening to identify the vulnerable plaque is still lacking. This is largely due to the absence of insight into the pathophysiology of vulnerable plaque and thus the lack of cost-effective interventions. Since the genesis of microcalcification is considered one of the earliest precursor processes in the formation of vulnerable plaque [2, 22], adequate early intervention and prevention are possible. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that drive microcalcification as well as the underlying mechanisms. However, the vast majority of so-called ‘vulnerable’ plaques do not exhibit clinical ‘instability’ and indeed seldom induce ACS [23]. Due to effective treatment, i.e. with statins, lesions became more stable. These lesions underlying superficial erosion do not have thin fibrous caps, have fewer inflammatory cells and lack a large lipid core. Rather they are more collagen-rich lesions and have more calcification, but they are still prone to form occlusive thrombi [23]. These considerations, taken together, indicate the high promise of vascular calcification as a new target for diagnosis and intervention in cardiovascular diseases, with an urgent need to translate experimental findings into adequate diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic solutions.

18F-FDG PET imaging of atherosclerosis

The strength of nuclear medicine is its ability to provide quantitative information at a functional level, such as the density of a specific receptor or the metabolic activity of a plaque. Nuclear imaging is based on radiolabelled biomarkers with a signal sensitivity in the picomolar range, which compares favourably with both MRI and especially CT, both of which have sensitivities up to a trillion times lower [21, 22]. PET images are derived from the detection of positron-emitting radionuclides labelling biochemical and metabolic substrates. The radionuclide is administered intravenously and circulates within the body. This allows time for the tracer to accumulate at the site of interest. To obtain a favourable target-to-background ratio, the radionuclide should be cleared from the blood quickly. The high sensitivity of PET coupled with the favourable resolution of CT and MRI, as already achieved in PET/CT and PET/MRI hybrid imaging systems provides valuable information about the localization of the acquired signal [24,25,26].

To obtain good quality images a high target-to-background ratio is mandatory for vascular PET imaging, for which the radiotracer must show high uptake in the target and preferably also rapid clearance from the bloodstream. Due to the small size of plaques, a high background activity mainly in the blood would severely impair the quality of PET images. Furthermore, coronary artery imaging presents special problems. Cardiac and respiratory movement, myocardial tracer uptake, especially of 18F-FDG, and the small size (3 to 4 mm) of the coronary arteries may impair and even preclude imaging of the coronary arteries by PET. Whereas motion artefacts can be reduced by using modalities such as cardiac gating, especially with the relatively slow PET data acquisition, suppression of the unwanted myocardial 18F-FDG uptake might be achieved using a different available dietary protocols [21, 22].

The radioactive tracer most commonly used clinically for PET imaging is 18F-FDG. 18F-FDG is mainly used for oncological studies and is well-established for the diagnosis and staging of malignant tumours and the monitoring of therapy response. The tracer is transported into cells by glucose transporters and is phosphorylated by hexokinase to 18F-FDG-6-phosphate that is not further metabolized [27]. The degree of cellular 18F-FDG uptake is related to the metabolic rate and the number of glucose transporters [28]. Therefore, increased 18F-FDG uptake in malignant tumour cells is partly due to an increased number of glucose transporters found in these cells. An increased number of glucose transporters is also found in activated inflammatory cells, such as macrophages. Additionally, the affinity of glucose transporters for deoxyglucose is apparently increased in these cells under inflammatory conditions by various cytokines and growth factors [27, 29]. However, potential competition between 18F-FDG and nonradioactive stable glucose for uptake in metabolically active cells (for example, inflammatory) might affect the imaging results in patients with high prescan glucose levels. Furthermore, an excess of unlabelled glucose and the action of insulin may increasingly affect the accumulation of 18F-FDG due to saturation of the glucose transporters [30, 31]. In addition, increases in plasma insulin levels result in translocation of the GLUT-4 transporters from an intracellular pool to the plasma membrane [32, 33]. This may enhance the uptake of 18F-FDG in myocardial and skeletal muscle, which in turn could significantly impair the quality and interpretability of 18F-FDG PET scans. This issue needs to be kept in mind particularly in patients with diabetes who are frequently affected by atherosclerosis, as diabetes is one of the main cardiovascular risk factors [34,35,36,37,38,39].

18F-FDG PET in preclinical studies

Methodological considerations of preclinical PET imaging of atherosclerosis

The availability of dedicated small-animal PET as well as hybrid PET/CT and now PET/MRI systems offers and facilitates the widespread use of preclinical PET imaging of atherosclerosis. This is crucial not only to understand the pathophysiology of the development and progression of atherosclerosis in vivo, but also to evaluate newly developed PET tracers for functional imaging of atherosclerosis. This also applies to PET tracers originally introduced into clinical routine for other indications, for example 68Ga-DOTATATE for the imaging of neuroendocrine tumours and 18F-fluorocholine (18F-FCH) for the (former) imaging of prostate cancer disease. To investigate their ability to enhance the visibility of atherosclerosis on PET they can be tested in vivo in a preclinical setting and correlated with histology for imaging distinct parts of the disease process.

The most common tool used in preclinical studies of atherosclerosis is still genetically modified mouse models [40]. Using these mouse models has provided a deep insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms in atherosclerosis despite obvious and well-known differences between human and murine atherosclerosis – including vessel architecture, plaque composition and stability [40,41,42]. The currently available genetically modified mouse models are suitable for initial evaluation of new PET tracers for atherosclerosis imaging. However, several steps of the human atherosclerotic disease process still cannot be covered by the available preclinical mouse models, impairing comparison with and translation to the human situation [40]. Therefore, attempts are being made to develop more appropriate mouse models to study plaque rupture [43]. Suggested models are brachiocephalic plaque disruption in aged apoE-null mice fed a high fat diet [44], plaque rupture in the brachiocephalic artery in mice fed a high fat diet and receiving angiotensin II [45] or warfarin [46], transfection of mice with haematopoietic stem cells with overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) [47] or urokinase plasminogen-activator (uPA) in macrophages [48], or collar placement on the carotid artery in apoE-null mice with stimulation with lipopolysaccharide and phenylephrine [49]. The suitability of these mouse models for mimicking atherosclerosis in humans more closely has to be proven in the near future.

Another approach to overcoming the shortcomings of atherosclerotic mouse models is the use of larger species for preclinical imaging such as rabbit or porcine models. Because of their greater size, rabbit arteries are large enough for more detailed analysis of arterial plaque components by PET, MRI and CT. This also allows serial imaging analysis in the context of interventional studies testing for strategies in plaque stabilization and/or regression, for example by applying lipid-lowering drugs. The size of rabbit arteries also allows the placement of, for example, endovascular stents, a model which can be used for the assessment of re-endothelialization of vascular therapeutic devices measured using PET [50, 51].

Recently, a rabbit model of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques has been introduced, and seems to overcome the absence of an appropriate mouse model for this purpose. This model consists of placing a vascular (arterial) injury in rabbits receiving a hyperlipidaemic diet [52,53,54]. Of all preclinical models representative of the clinical situation, porcine models may be the best option for the investigation of atherosclerosis. Pigs not only exhibit vessel wall architecture similar to that in humans, but also respond in the same way as humans to exposure to oxidized LDL. Furthermore, they develop atheroma lesions in response to insulin resistance and also develop vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques [43, 55, 56]. Besides the pathophysiological similarities between porcine and human plaques, another advantage of using porcine atherosclerosis models is related to the size of the porcine vessels, which are sufficiently large to enable the evaluation of not only small vessels such as the coronary arteries but also neointimal hyperplasia and neovascularization. Furthermore, PET imaging of smaller arterial structures is also facilitated by the larger vessel size, which is crucial because of the rather low spatial resolution of PET compared with that of CT and MRI [57].

From a technical point of view, the combination of noninvasive imaging methodologies such as PET and CT or MRI facilitates efforts to develop new preclinical models for atherosclerosis imaging. Such models would allow not only evaluation of the functional aspects of a ‘vulnerable’ atherosclerotic plaque with PET, but also determination of the precise location as well as morphological parameters of atherosclerotic lesions with CT or MRI.

Unquestionably, animal models are indispensable to the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that underlie human atherosclerosis and plaque vulnerability. Each animal model has its own advantages and disadvantages concerning cost and the possibility of modulating cell and cellular factors that influence the atherogenic process. In order to answer a research question properly, the correct choice of animal model is decisive.

Preclinical imaging studies with 18F-FDG PET

Preclinical studies indicating that 18F-FDG PET might have a role in imaging atherosclerosis have been performed in cholesterol-fed rabbits. A positron-sensitive fibre-optic probe placed in contact with the arterial intima was able to detect high 18F-FDG uptake in atherosclerotic segments of the iliac artery [58]. That 18F-FDG is able to identify vulnerable plaque was demonstrated in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis in which plaque rupture was promoted by venom injection. Aziz et al. found that only the aortic plaques with the highest preinjection 18F-FDG uptake progressed to rupture and thrombosis [59]. The suitability of 18F-FDG PET for the investigation of therapeutic interventions was shown in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis in which there was a significant reduction in 18F-FDG uptake after 3 months of therapy with a lipid-lowering antioxidant agent [60].

Imaging atherosclerosis with 18F-FDG PET also has potential drawbacks. 18F-FDG was administered intravenously to atherosclerotic LDLR/ApoB48 mice and control mice and the ex vivo distribution in frozen aortic sections was measured by digital autoradiography [61]. Additionally, in vitro uptake of 18F-FDG in human atherosclerotic arteries was also examined. Unexpectedly, significant 18F-FDG uptake was found in the vicinity of calcified structures atherosclerotic plaques in mice. This uptake seemed to be more prominent than in noncalcified atherosclerotic plaques. The in vitro studies of atherosclerotic human arteries showed similar results with marked uptake of 18F-FDG in the calcifications but not in other structures of the artery wall.

To overcome the limitations of 18F-FDG PET imaging of atherosclerosis, PET tracers originally introduced for imaging other indications (such as oncological or neurological disorders) have been used in numerous preclinical studies to evaluate potential candidates for screening of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. In these studies, different PET tracers were used to those used in preclinical models; for example, 18F-FCH and 18F-labelled analogues of CGS 27023A for imaging MMPs, and 124I-labelled platelet glycoprotein VI (124I-GPVI) for imaging thrombosis at sites of atherosclerotic lesions [62,63,64,65].

18F-FDG PET imaging in clinical studies

Arterial 18F-FDG uptake was first noted in the aorta of patients undergoing 18F-FDG PET for cancer imaging [66]. It was also shown that the amount of 18F-FDG uptake increased with age and was higher in patients with cardiovascular risk factors [29, 67, 68]. Supported by cell culture work, 18F-FDG uptake in the arterial wall can probably be attributed to uptake in plaque macrophages. These studies demonstrated that increased oxidative metabolism and glucose use in response to cellular activating agents is accompanied by a dramatic increase in 18F-FDG uptake in both leucocytes and macrophages [36, 69].

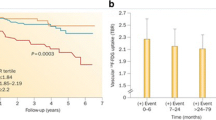

Following the dedicated preclinical studies of the use of 18F-FDG PET for imaging atherosclerosis, Rudd et al. performed one of the first clinical studies of atherosclerosis imaging with 18F-FDG PET in patients with transient ischaemic attack [70]. The patients were scanned shortly after symptom onset and a significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake (almost 30%) was seen in symptomatic carotid plaques than in the asymptomatic artery [70]. This indicates the feasibility of 18F-FDG PET for the imaging of inflammation in the aorta, and in peripheral and vertebral arteries [71,72,73]. The relationship between uptake of 18F-FDG and inflammation has been demonstrated using histology linking 18F-FDG uptake with the number of macrophages in arterial specimens [74, 75]. In addition to findings indicating 18F-FDG uptake as a marker of arterial inflammation, preliminary studies have indicated that 18F-FDG has the potential to predict plaque rupture as well as clinical events. Regarding the predictive value of 18F-FDG PET, in a study including more than 2,000 patients with cancer disease, Paulmier et al. found that, compared with patients with a low arterial 18F-FDG uptake, patients with the highest 18F-FDG uptake were more likely to have either a previous vascular event or to experience an event during the 6 months after PET imaging [76]. Furthermore, the short-term interscan reproducibility of 18F-FDG PET in the imaging of atherosclerosis has been shown to be excellent for the carotid artery, aorta and peripheral arteries [69, 71, 73, 77]; this is an important finding mainly for the use of 18F-FDG PET as an endpoint parameter in intervention studies.

Despite the widespread use of 18F-FDG PET/CT in cardiovascular disease, nonspecific uptake of the tracer is undoubtedly the most important drawback of the use of 18F-FDG for imaging atherosclerosis [54]. 18F-FDG is nonspecifically taken up by almost all human tissues and organs to a certain degree. 18F-FDG uptake analysis in arterial and/or venous vessels is therefore hampered by significant spill-over of tracer signal from closely neighbouring structures; for example, 18F-FDG uptake in the thyroid gland during carotid PET imaging or myocardial 18F-FDG uptake during PET imaging of the thoracic aorta or coronary arteries. Furthermore, pathologically increased 18F-FDG uptake in structures close to the target vessel further impair 18F-FDG uptake analysis in atherosclerotic plaques; for example, inflamed cervical lymph nodes close to the carotid arteries. More importantly, significant 18F-FDG uptake has been found in atherosclerosis-prone mice in the vicinity of calcified structures in plaques, and this has been confirmed in in vitro studies of atherosclerotic human arteries that showed marked binding of 18F-FDG to calcifications but not to other structures of the artery wall [61]. On the basis of these findings taken together, studies to evaluate new or already existing PET tracers currently used for indications other than atherosclerosis are warranted. These PET tracers might be more specific and possibly more sensitive for detecting high-risk vulnerable plaques.

Beyond 18F-FDG: PET radiotracers for target identification in atherosclerosis

18F-Fluorocholine

18F-FCH was introduced several years ago for imaging the brain and for diagnosis of prostate cancer disease [78, 79]. Choline is taken up into cells by specific transport mechanisms and phosphorylated by choline kinase. Increased choline uptake has been shown both in tumour cells and in activated macrophages [80, 81]. Previously published studies demonstrated enhanced 18F-FCH uptake after soft tissue infection or acute cerebral radiation injury that correlated well with macrophage accumulation as part of an inflammatory reaction [82, 83]. In a murine model of atherosclerosis, ex vivo imaging with 18F-FCH provided better identification of plaques than imaging with 18F-FDG, indicating that this tracer may be a promising candidate for imaging plaques in patients [62].

The first feasibility study of the use of 18F-methylcholine (18F-FMCH) PET for imaging arterial plaques was performed in five patients undergoing imaging for prostate cancer [84]. Morphological classification of vessel wall alterations in the abdominal aorta and the common iliac arteries included structural wall alterations without additional calcifications, structural wall alterations associated with calcifications, and solely calcified lesions. The use of 18F-FMCH was shown to be feasible for in vivo imaging of structural vessel wall alterations in humans, which provided the basis for several subsequent studies on vascular 18F-FCH PET imaging [84]. Confirming these results, Kato et al. reported the results of a retrospective study of the use of 11C-choline PET imaging of vascular plaques in 93 patients with prostate cancer [85]. 11C-Choline uptake was found in 95% of the patients and calcification in 94% throughout all vessel segments. However, colocalization of choline uptake with calcifications was found in only 6% of the patients. Furthermore, less than 1% of calcification sites showed increased radiotracer uptake. Thus, in concordance with the previous data, 11C-choline uptake and calcification were found to be only rarely colocalized [84, 85]. Because of the high uptake of 11C-choline and the high proportion of calcifications without colocalization, 11C-choline potentially provides information about atherosclerotic plaques independent of calcification measurement [85].

In a retrospective study including 60 patients with prostate cancer examined with whole-body PET/CT using 18F-fluoroethylcholine (18F-FEC), uptake in the wall of the ascending and descending aorta, aortic arch, abdominal aorta, and both iliac arteries was measured, and the sum of calcified plaques (CPsum) in these vessels was also calculated. These data were correlated with the presence of cardiovascular risk factors and occurrence of prior cardiovascular events [86]. CPsum was significantly correlated with cardiovascular risk factors. However, no significant association was found between 18F-FEC uptake in large vessels and atherosclerotic plaque burden, in contrast to the studies by Bucerius et al. and Kato et al. [84, 85]. It is noteworthy that the lack of an association between choline uptake and calcified arterial plaque burden reported by Förster et al. was also seen in the two previous studies of vascular choline PET imaging [84,85,86]. Recently, a prospective study including ten consecutive stroke patients with ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis of >70% was reported. Patients were scheduled for carotid endarterectomy and underwent PET for the assessment of the maximum 18F-FCH uptake in the ipsilateral symptomatic carotid plaques and contralateral asymptomatic carotid arteries [87]. The PET imaging results were correlated with histological evaluation of the macrophage content in all carotid endarterectomy specimens as the CD68+ staining percentage per whole plaque area and as the maximum CD68+ staining percentage in the most inflamed section/plaque. A strong correlation between 18F-FCH uptake in the carotid atherosclerotic plaque and degree of macrophage infiltration indicates that 18F-FCH PET is a promising tool for the evaluation of vulnerable plaques [87].

68Ga-DOTATATE

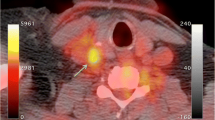

68Ga-DOTATATE PET imaging has gained widespread acceptance in clinical routine for imaging somatostatin receptor-positive neuroendocrine tumours. These somatostatin receptors of subtype 2 are also expressed by macrophages and can therefore be detected by 68Ga-DOTATATE PET imaging [88,89,90]. One advantage compared to 18F-FDG is that 68Ga-DOTATATE does not show physiological uptake in the myocardium. Therefore, besides imaging of the carotid arteries (Figs. 1 and 2) and aorta, imaging of the coronary arteries with 68Ga-DOTATATE seems feasible, independent of the still unresolved methodological issues such as inappropriate spatial and temporal resolution related to coronary PET imaging. Rominger et al, determined the uptake of 68Ga-DOTATATE in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) in a series of 70 oncological patients undergoing 68Ga-DOTATATE whole-body PET/CT [90]. 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake was detectable in the LAD of all patients and correlated significantly with the presence of calcified plaques and prior vascular events. Calcified plaque burden was also correlated with prior vascular events and with patient age and the presence of hypertension. Therefore, the use of 68Ga-DOTATATE seems feasible for the imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in coronary arteries.

Fused PET/CT images show only slight 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake at the bifurcation of the left carotid artery with, on the CT images, as part of the fused PET/CT images, visible calcification (arrow). Combined molecular (68Ga-DOTATATE PET) and morphological imaging (CT) indicates more stable, chronic arterial vessel wall changes

Li et al. compared the uptake of 68Ga-DOTATATE and 18F-FDG in eight arterial segments in 16 patients with neuroendocrine tumours or thyroid cancer who underwent PET imaging with both tracers for staging or restaging [91]. 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake in all large arteries was correlated significantly with the presence of calcified plaques, the presence of hypertension, age and uptake of 18F-FDG. In contrast, 18F-FDG uptake was significantly correlated only with the presence of hypertension. Of the 37 sites with the highest focal 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake, 16 (43.2%) also had focal 18F-FDG uptake. In contrast, of 39 sites with the highest 18F-FDG uptake, only 11 (28.2%) showed colocalization with 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake. Thus, 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake seems to be more strongly associated with known risk factors of cardiovascular disease than 18F-FDG uptake. Interestingly, focal uptake of 68Ga-DOTATATE was shown not to be colocalized with 18F-FDG uptake in a significant number of lesions [91]. The disparity between these two tracers seems to reflect the fact that 68Ga-DOTATATE is a specific macrophage marker in atherosclerosis in contrast to 18F-FDG, whereas 18F-FDG provides a nonspecific measurement of glucose metabolism of cells within the atherosclerotic plaque. Furthermore, 68Ga-DOTATATE might offer a more ‘focal’ approach in imaging atherosclerotic lesions than 18F-FDG [92].

64Cu-DOTATATE can also be used in combination with vascular hybrid PET/MRI imaging to evaluate atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries [93]. Significantly higher 64Cu-DOTATATE uptake was found in symptomatic plaques than in the contralateral carotid artery. In a subsequent analysis, a total of 62 plaque segments were assessed for gene expression of selected markers of plaque vulnerability. A univariate analysis comparing these results with 64Cu-DOTATATE uptake in vivo showed that CD163 and CD68 gene expression was correlated weakly although significantly with the mean standardized uptake values in the PET scans. In a multivariate analysis CD163 was correlated independently with the 64Cu-DOTATATE uptake, whereas CD68 was not, indicating that 64Cu-DOTATATE-PET might detect alternatively activated macrophages.

18F-Sodium fluoride

18F-NaF is a positron-emitting bone-seeking agent which reflects blood flow and remodelling of bone. Therefore, 18F-NaF has received attention in the field of imaging alterations in calcification in atherosclerotic plaques. In a feasibility study, Derlin et al. retrospectively evaluated imaging data from 75 patients undergoing whole-body 18F-NaF PET/CT [94]. 18F-NaF uptake was observed at 254 sites in 57 patients (76%) and calcification was observed at 1,930 sites in 63 patients (84%). Colocalization of radiotracer accumulation and calcification was observed in 223 areas of uptake (88%). Interestingly, only 12% of all arterial calcification sites showed increased radiotracer uptake, indicating that 18F-NaF might be much more sensitive in detecting so-called spotty calcifications than CT. The same group investigated 18F-NaF uptake in the common carotid arteries of neurologically asymptomatic patients with cardiovascular risk factors and carotid calcified plaque burden [95]. They included 269 oncological patients who underwent 18F-NaF PET/CT. 18F-NaF uptake in the common carotid arteries was observed at 141 sites in 94 patients (34.9%) and showed colocalization with calcification in all atherosclerotic lesions. 18F-NaF uptake was significantly associated with age, male sex, and the presence of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. The presence of calcified atherosclerotic plaques was correlated significantly with these risk factors and also with diabetes, history of smoking and prior cardiovascular events. Furthermore, a highly significant correlation was found between 18F-NaF uptake and the number of cardiovascular risk factors.

Intriguing results of a prospective clinical trial of vascular 18F-NaF PET imaging have been reported [96]. Both 18F-NaF and 18F-FDG PET/CT and invasive coronary angiography were performed in 40 patients with myocardial infarction and 40 patients with stable angina. 18F-NaF uptake was compared with histology in carotid endarterectomy specimens from patients with symptomatic carotid disease, and with intravascular ultrasonography in patients with stable angina. In 37 patients (93%) with myocardial infarction, the highest coronary 18F-NaF uptake was seen in the culprit plaque. Interestingly, in contrast to the findings for 18F-NaF (which is not physiologically taken up by the myocardium), coronary 18F-FDG uptake was commonly obscured by myocardial uptake and where discernible, there were no differences between culprit and nonculprit plaques. At the sites of carotid plaque rupture, significant 18F-NaF uptake was observed, and was associated with histological evidence of active calcification, macrophage infiltration, apoptosis and necrosis [96]. Coronary atherosclerotic plaques with focal 18F-NaF uptake were seen in 18 patients (45%) with stable angina. Intravascular ultrasonography in these patients revealed more high-risk features in plaques with increased 18F-NaF uptake, such as positive remodelling, microcalcification and necrotic core, than in plaques without 18F-NaF uptake. These promising results indicate, that 18F-NaF PET imaging might be a sensitive method for identifying and localizing ruptured and high-risk coronary plaques.

Irkle et al. reported intriguing results of an extensive analysis of vascular 18F-NaF binding using electron microscopy, autoradiography, histology and preclinical and clinical PET/CT [97]. 18F-NaF was found to directly adsorb to calcified areas in mineralized vascular tissue and this binding was found to be highly specific, as 18F-NaF uptake was seen solely in calcification with no localization in other soft tissues. Furthermore, 18F-NaF uptake was found to be highly dependent on the surface area of the calcification. The tracer was only absorbed to the outer layer of calcification regions, suggesting that 18F-NaF only detects active mineralization [97]. Fiz et al. found that 18F-NaF hot spots were present in atherosclerotic plaques in 86% of patients at sites without visible calcification on CT [98]. These findings suggest that 18F-NaF localizes at sites of microcalcification that are invisible on CT at the current clinical resolution, and strongly suggest that microcalcifications are a cause of atherosclerosis rather than a consequence [2]. Additionally, mice treated with warfarin (vitamin K antagonist) showed 18F-NaF hotspots in the abdominal aorta within 2 weeks of treatment, indicating that drug-induced inactivation of vitamin K-dependent proteins results in early active mineralization (unpublished data; Fig. 3).

Sprague Dawley rats at 10–12 weeks of age were subjected to either a chow diet or a chow diet supplemented with warfarin (3 mg/g + 1.5 mg/g K1) for 2 weeks. a b 18F-NaF PET/CT images obtained after 2 weeks in animals on the chow diet (a) and in animals on the warfarin-supplemented chow diet (b): animals on the supplemented diet show uptake in the descending aorta indicating hotspots of calcification which are not seen in the animals on the chow diet. c Ex vivo histochemical Alizerin Red staining of aortic tissue reveals calcification of the vasculature

The characteristic properties of 18F-NaF as a highly specific ligand for the detection of pathologically high-risk microcalcification, and therefore early unstable atherosclerotic disease, makes it a highly valuable tracer for noninvasive evaluation in human high-risk atherosclerotic plaques.

The future: novel PET radiotracers

18F-Aluminium labelling

For routine PET imaging, 18F is today the best radionuclide with a half-life (T½) of 109.8 min and low β+ energy (0.64 MeV). Compared with other short-lived radionuclides, such as 11C (T½ = 20.4 min), its half-life is long enough to allow synthesis and imaging procedures to be extended over hours, enabling kinetic studies and high-quality metabolite and plasma analysis.

Efficient 18F labelling of peptides and proteins is often a multistep process involving labelling and purification of a prosthetic group (synthon) and subsequent conjugation of the 18F-labelled synthon to the peptide/protein with or without activation. If necessary, the 18F conjugate is purified by a final purification step. Over the years, a variety of prosthetic groups have been developed ranging from amine-reactive groups such as N-succinimidyl-4-[18F]fluorobenzoate ([18F]SFB) [99] to chemoselective groups, for example 4-[18F]fluorobenzaldehyde and 18F-FDG [100, 101], that react with an aminooxy-modified or hydrazine-modified peptide.

A special prosthetic group approach that has been explored in 18F labelling chemistry is click chemistry methodology. Click chemistry appears to be an effective method for radiolabelling peptides and proteins, because the click reaction is fast, bioorthogonal, chemoselective and regioselective, and results in relatively high yields and can be performed in aqueous media. This copper(I)-catalysed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction has been exploited in radiopharmaceutical chemistry by several research groups [101,102,103,104,105,106]. A variant of the copper(I)-catalysed click reaction is the copper-free click reaction that does not require the use of the cytotoxic metal. Reactions of electron-deficient tetrazines with ring-trained trans-cyclooctenes or norbenes have been investigated [107,108,109,110,111]. Click reactions, Cu(I)-catalysed and copper-free, have been shown to be powerful and versatile reactions for the synthesis of 18F-labelled peptides and proteins.

Although there are a variety of possible methods for introducing 18F into a peptide or protein, a major drawback of the 18F-labelling methods described above is that they are labourious (require azeotropic drying of the fluoride and multiple purification steps) and thus time-consuming. In search of a kit-based 18F-labelling method, new 18F-labelling strategies based on fluorine–silicon [112,113,114,115], fluorine–boron [116,117,118], and fluorine–phosphorus [119] have been developed. A straightforward chelator-based approach to labelling peptides and proteins with 18F was proposed in 2009 by McBride et al. [120]. They demonstrated that it is feasible to radiofluorinate compounds by first creating a stable 18F-Al complex which can subsequently be attached to the compound via a chelator. The 18F-Al labelling procedure has recently been significantly improved by optimizing chelators and labelling conditions [121]. This 18F-labelling technique has been demonstrated to be applicable to many peptides and proteins and has proved to be a versatile approach, especially for peptides and proteins that are not stable under harsh labelling conditions.

Peptide-based and protein-based PET radiotracers

18F-NaF has excellent pharmacokinetic properties (i.e. fast blood clearance, urinary excretion, high uptake in regenerating bone, minimal binding to serum proteins) and in 1972 was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use as a clinical PET tracer [122]. Although the studies discussed above show that 18F-NaF is a suitable tracer for the detection of (early) vascular microcalcifications, uptake of 18F-NaF in these lesions is not specific, hampering elucidation of pathological molecular mechanisms. To define potential treatment targets based on underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, radiotracers that specifically bind to vascular calcification-specific biomarkers (i.e. receptors, enzymes, proteins) are necessary. In addition, it is difficult to distinguish intimal from medial calcification with noninvasive imaging techniques and specific radiotracers are necessary to differentiate between these two vascular calcification entities.

To investigate and decipher the underlying molecular mechanisms that result in vascular calcification, design and synthesis of smart diagnostic nuclear imaging probes is an appropriate approach. Multimodality molecular imaging now plays an important role in preclinical research as it combines the strengths of different imaging modalities to elucidate molecular basics of diseases, e.g. PET, single photon emission tomography (SPECT), fluorescence, and contrast-enhanced MRI. Specific imaging probes which combine optical imaging with nuclear medicine imaging modalities (SPECT/CT and PET/CT) are under development and enable additional ex vivo tissue analysis using microscopy to analyse lesions at the (sub)cellular level after a SPECT/CT or PET/CT scan. These multimodal tracers will mainly be used in preclinical imaging studies. There is also a role for these probes in clinical studies during intraoperative surgery.

During recent decades, the utility of radiolabelled peptides and proteins in preclinical and clinical research studies has been proven. Solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) is currently the preferred technique for the production of synthetic peptides and proteins. Chemical protein synthesis allows unlimited variation of the polypeptide chain by incorporation of nonnatural amino acids such as d-amino acids, and fluorescent or affinity tags, chelators for metal ions or radioisotopes for use in MRI, PET and SPECT, at single specific sites. Selective protein modification at single sites cannot be achieved through regular labelling of biologically obtained proteins. Current optimized SPPS chemistry protocols enable effective peptide synthesis of 30–50 amino acids. For the synthesis of peptides and proteins larger than 30–50 amino acids, breakthrough ‘native chemical ligation’ (NCL) technologies have been developed that enable the formation of a peptide bond between two unprotected peptides resulting in larger synthetic proteins (50–200 amino acids) with a fully native peptide backbone [123, 124]. NCL can also be used to efficiently introduce labels into chemically synthesized proteins [125].

For site-specific conjugation of a multimodal label (fluorophore and chelator; Fig. 4) to a protein, two strategies have been designed and optimized by our research group. One strategy uses a thiaproline residue appended to a lysine sidechain (Lys[Thz]), as an unlockable thiol handle that enables orthogonal modification of prefolded proteins [126]. This method is compatible with Boc-based SPPS, NCL, and standard methods for disulfide bridge formation. The other strategy is based on aniline-catalysed oxime bond formation [127]. Oxime ligations comprise chemoselective mild reactions of a ketone or aldehyde with an aminooxy to form oximes which are stable at neutral pH [128]. Because the widely used levulinoyl ketone group undergoes intramolecular rearrangement, a novel oxime ligation strategy has been developed with 3-(2-oxopropyl)-benzoic acid as a ketone moiety that appears to give higher oxime ligation rates and yields [129].

Left: Model of chemokine CCL5 synthesized by Boc-based SPPS and NCL. An extra lysine residue was coupled at the C-terminus of CCL5. Subsequently, a bimodal rhodamine/DTPA label was conjugated through an oxime bond. Right: Confocal microscopy imaging of mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMMs) and 3T3 fibroblasts. a DIC contrast image of BMMs; b Merged image of BMMs stained with CCL5–rhodamine/DTPA (1,500 nM) and with SYTO13 (2 μM; nuclei staining); c DIC contrast image of 3T3 fibroblasts; d Merged image of 3T3 fibroblasts stained with CCL5–rhodamine/DTPA (1,500 nM) and SYTO13 (2 μM)

The techniques described above are used and will be used to synthesize and radiolabel (multimodal) peptide-based molecular imaging agents. An interesting biomarker of vascular calcification is matrix Gla protein (MGP; Fig. 5) [16]. This protein consists of 84 amino acids and requires vitamin K-dependent gamma-carboxylation for its function [130]. It is mainly expressed by chondrocytes, VSMCs, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. MGP binds calcium crystals, inhibits crystal growth and plays a role in preventing osteoblastic differentiation of normal VSMCs [131, 132]. As MGP binds calcium crystals, it may be a suitable molecular imaging probe for the investigation of early vascular calcium deposits. Moreover, since uncarboxylated MGP seems to precede microcalcification, detection of inactive MGP might be an interesting alternative [2, 133].

Vitamin K metabolism in the secretion of vitamin K-dependent MGP. Scheme of the vitamin K cycle: in the endoplasmic reticulum, posttranslational modification of Glu to Gla residues via reduction of vitamin K to the hydroquinone form (KH2). KH2 is oxidized to KO by the enzyme GGCX thereby facilitating the carboxylation of ucMGP to cMGP. The enzyme VKOR recycles KO back to K and KH2 so that vitamin K can be used some 1,000 times. VKA inhibits VKOR and thus the recycling of vitamin K. This causes a vitamin K deficiency with subsequent ucMGP formation. UcMGP is inactive thereby allowing the formation of microcalcifications

Another interesting biomarker in vascular calcification is bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). BMP-2 is a 114 amino acid protein which transforms undifferentiated cells and subpopulations of VSMCs into bone-forming cells [134, 135]. BMP also binds calcium crystals and thus can be used as a molecular imaging probe. Osteocalcin (OC) is another vitamin K-dependent protein that can be used as a molecular imaging probe for vulnerable plaque [136]. This 49 amino acid protein inhibits calcium salt precipitation in vitro [137] and is strongly upregulated in advanced atherosclerotic lesions [138].

As well as the proteins discussed above, there are other promising imaging probe candidates. Antibodies or preferably antibody fragments that specifically bind to these proteins are of great interest for the development of suitable tracers for molecular imaging of molecular processes early in the initiation of microcalcification. Moreover, peptides and proteins that bind to receptors, enzymes or proteins that are upregulated during vascular calcification are promising candidates. The development of new imaging agents requires a multistep approach, including target selection, organic synthesis of molecular imaging agents, optimization of target affinity and pharmacokinetic profile of the tracer, and preclinical evaluation.

Conclusion

Atherosclerosis is a multifactorial process that involves both local and systemic processes. The vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque cannot simply be detected by plaque size, and thus identification of molecular and cellular processes underlying plaque vulnerability is crucial for diagnosis and treatment (Fig. 6). Recent progress in imaging has improved detection of atherosclerotic lesions and has led to the ability to screen for vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. Combining expertise in biology, chemistry, nuclear medicine and cardiology will advance our understanding of critical determinants of the high-risk plaque and result in tailor-made imaging radiotracers to differentiate the vulnerable plaque. Ultimately, this strategy will open novel avenues for diagnosis and treatment of the patient with high-risk disease.

Different types of vascular calcification can occur in the vasculature. Vascular calcification is clinically measured by CT and represents the amount of vascular burden. Moreover, calcification detected on CT in the media relates to vascular stiffness. However, microcalcification cannot be visualized by CT and these early stages of calcification can now be detected by 18F-NaF PET. Microcalcifications are responsible for destabilizing the plaque, causing an increased risk of plaque rupture. They also cause vascular remodelling when present in the vascular media. The measurement of inactive MGP as a marker of increased risk of the formation of microcalcifications is currently under development

References

van Varik BJ, Rennenberg RJ, Reutelingsperger CP, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW, Schurgers LJ. Mechanisms of arterial remodeling: lessons from genetic diseases. Front Genet. 2012;3:290.

Chatrou MLL, Cleutjens JP, van der Vusse GJ, Roijers RB, Mutsaers PHA, Schurgers LJ. Intra-section analysis of human coronary arteries reveals a potential role for micro-calcifications in macrophage recruitment in the early stage of atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142335.

Koenen R, Weber C. Therapeutic targeting of chemokine interactions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:141–53.

Bennett MR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:692–702.

Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801.

Sata M, Saiura A, Kunisato A, Tojo A, Okada S, Tokuhisa T, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2002;8:403–9.

Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, et al. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat Med. 2015;21:628–37.

Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-sex-race/ethnicity percentiles: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:345–52.

Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95.

Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Figueiredo J, Swirski F, Shtatland T, Kohler R, et al. Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:2841–50.

Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43.

Liberman M, Bassi E, Martinatti M, Lario F, Wosniak J, Pomerantzeff P, et al. Oxidant generation predominates around calcifying foci and enhances progression of aortic valve calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:463–70.

Byon C, Javed A, Dai Q, Kappes J, Clemens T, Darley-Usmar V, et al. Oxidative stress induces vascular calcification through modulation of the osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 by AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15319–27.

Doherty TM, Detrano RC. Coronary arterial calcification as an active process: a new perspective on an old problem. Calcif Tissue Int. 1994;54:224–30.

Rennenberg RJ, Kessels AG, Schurgers LJ, van Engelshoven JM, de Leeuw PW, Kroon AA. Vascular calcifications as a marker of increased cardiovascular risk: a meta-analysis. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:185–97.

Schurgers LJ, Uitto J, Reutelingsperger CP. Vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of matrix Gla-protein: a crucial switch to control ectopic mineralization. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:217–26.

Ehara S, Kobayashi Y, Yoshiyama M, Shimada K, Shimada Y, Fukuda D, et al. Spotty calcification typifies the culprit plaque in patients with acute myocardial infarction: an intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2004;110:3424–9.

Kapustin AN, Chatrou MLL, Drozdov I, Zheng Y, Davidson SM, Soong D, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell calcification is mediated by regulated exosome secretion. Circ Res. 2015;116:1312–23.

Vengrenyuk Y, Carlier S, Xanthos S, Cardoso L, Ganatos P, Virmani R, et al. A hypothesis for vulnerable plaque rupture due to stress-induced debonding around cellular microcalcifications in thin fibrous caps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14678–83.

Aikawa E, Nahrendorf M, Sosnovik D, Lok V, Jaffer F, Aikawa M, et al. Multimodality molecular imaging identifies proteolytic and osteogenic activities in early aortic valve disease. Circulation. 2007;115:377–86.

Nadra I, Mason J, Philippidis P, Florey O, Smythe C, McCarthy G, et al. Proinflammatory activation of macrophages by basic calcium phosphate crystals via protein kinase C and MAP kinase pathways: a vicious cycle of inflammation and arterial calcification? Circ Res. 2005;96:1248–56.

Roijers RB, Debernardi N, Cleutjens JP, Schurgers LJ, Mutsaers PH, van der Vusse GJ. Microcalcifications in early intimal lesions of atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2879–87.

Libby P. How does lipid lowering prevent coronary events? New insights from human imaging trials. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:472–4.

Pichler BJ, Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF. PET/MRI hybrid imaging: devices and initial results. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1077–86.

Wehrl HF, Judenhofer MS, Wiehr S, Pichler BJ. Pre-clinical PET/MR: technological advances and new perspectives in biomedical research. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(Suppl 1):S56–68.

Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF, Newport DF, Catana C, Siegel SB, Becker M, et al. Simultaneous PET-MRI: a new approach for functional and morphological imaging. Nat Med. 2008;14:459–65.

Schillaci O, Danieli R, Padovano F, Testa A, Simonetti G. Molecular imaging of atherosclerotic plaque with nuclear medicine techniques. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22:3–7.

Pauwels EK, Ribeiro MJ, Stoot JH, McCready VR, Bourguignon M, Mazière B. FDG accumulation and tumor biology. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:317–22.

Yun M, Jang S, Cucchiara A, Newberg AB, Alavi A. 18F FDG uptake in the large arteries: a correlation study with the atherogenic risk factors. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:70–6.

Crippa F, Gavazzi C, Bozzetti F, Chiesa C, Pascali C, Bogni A, et al. The influence of blood glucose levels on [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in cancer: a PET study in liver metastases from colorectal carcinomas. Tumori. 1997;83:748–52.

Lindholm P, Minn H, Leskinen-Kallio S, Bergman J, Ruotsalainen U, Joensuu H. Influence of the blood glucose concentration on FDG uptake in cancer – a PET study. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:1–6.

Cheung JY, Conover C, Regen DM, Whitfield CF, Morgan HE. Effect of insulin on kinetics of sugar transport in heart muscle. Am J Phys. 1978;234:E70–8.

Sun D, Nguyen N, DeGrado TR, Schwaiger M, Brosius FC. Ischemia induces translocation of the insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4 to the plasma membrane of cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 1994;89:793–8.

Bucerius J, Mani V, Wong S, Moncrieff C, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Machac J, et al. Arterial and fat tissue inflammation are highly correlated: a prospective 18F-FDG PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:934–45.

Bucerius J, Hyafil F, Verberne HJ, Slart RHJA, Lindner O, Sciagra R, et al. Position paper of the Cardiovascular Committee of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) on PET imaging of atherosclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:780–92.

Deichen JT, Prante O, Gack M, Schmiedehausen K, Kuwert T. Uptake of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in human monocyte-macrophages in vitro. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:267–73.

Zhao S, Kuge Y, Tsukamoto E, Mochizuki T, Kato T, Hikosaka K, et al. Effects of insulin and glucose loading on FDG uptake in experimental malignant tumours and inflammatory lesions. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:730–5.

Zhao S, Kuge Y, Tsukamoto E, Mochizuki T, Kato T, Hikosaka K, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and glucose transporter expression in experimental inflammatory lesions and malignant tumours: effects of insulin and glucose loading. Nucl Med Commun. 2002;23:545–50.

Bucerius J, Mani V, Moncrieff C, Rudd JHF, Machac J, Fuster V, et al. Impact of noninsulin-dependent type 2 diabetes on carotid wall 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography uptake. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2080–8.

Cuadrado I, Saura M, Castejón B, Martin AM, Herruzo I, Balatsos N, et al. Preclinical models of atherosclerosis. The future of hybrid PET/MR technology for the early detection of vulnerable plaque. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2016;18:e6.

Boshuizen MCS, Hoeksema MA, Neele AE, van der Velden S, Hamers AAJ, Van den Bossche J, et al. Interferon-β promotes macrophage foam cell formation by altering both cholesterol influx and efflux mechanisms. Cytokine. 2016;77:220–6.

Getz GS, Reardon CA. Use of mouse models in atherosclerosis research. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1339:1–16.

Matoba T, Sato K, Egashira K. Mouse models of plaque rupture. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:419–25.

Johnson J, Carson K, Williams H, Karanam S, Newby A, Angelini G, et al. Plaque rupture after short periods of fat feeding in the apolipoprotein E-knockout mouse: model characterization and effects of pravastatin treatment. Circulation. 2005;111:1422–30.

Sato K, Nakano K, Katsuki S, Matoba T, Osada K, Sawamura T, et al. Dietary cholesterol oxidation products accelerate plaque destabilization and rupture associated with monocyte infiltration/activation via the MCP-1-CCR2 pathway in mouse brachiocephalic arteries: therapeutic effects of ezetimibe. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19:986–98.

Schurgers LJ, Joosen IA, Laufer EM, Chatrou MLL, Herfs M, Winkens MHM, et al. Vitamin K-antagonists accelerate atherosclerotic calcification and induce a vulnerable plaque phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43229.

Gough PJ, Gomez IG, Wille PT, Raines EW. Macrophage expression of active MMP-9 induces acute plaque disruption in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:59–69.

Hu JH, Du L, Chu T, Otsuka G, Dronadula N, Jaffe M, et al. Overexpression of urokinase by plaque macrophages causes histological features of plaque rupture and increases vascular matrix metalloproteinase activity in aged apolipoprotein e-null mice. Circulation. 2010;121:1637–44.

Ma T, Gao Q, Zhu F, Guo C, Wang Q, Gao F, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 are involved in the disruption of vulnerable plaques triggered by short-term combination stimulation in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10:338–48.

Fan J, Kitajima S, Watanabe T, Xu J, Zhang J, Liu E, et al. Rabbit models for the study of human atherosclerosis: from pathophysiological mechanisms to translational medicine. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;146:104–19.

Hyafil F, Tran-Dinh A, Burg S, Leygnac S, Louedec L, Milliner M, et al. Detection of apoptotic cells in a rabbit model with atherosclerosis-like lesions using the positron emission tomography radiotracer [18F]ML-10. Mol Imaging. 2015;14:433–42.

Zhao Q-M, Zhao X, Feng T-T, Zhang M-D, Zhuang X-C, Zhao X-C, et al. Detection of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque and prediction of thrombosis events in a rabbit model using 18F-FDG -PET/CT. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61140.

Abela GS, Picon PD, Friedl SE, Gebara OC, Miyamoto A, Federman M, et al. Triggering of plaque disruption and arterial thrombosis in an atherosclerotic rabbit model. Circulation. 1995;91:776–84.

Phinikaridou A, Ruberg FL, Hallock KJ, Qiao Y, Hua N, Viereck J, et al. In vivo detection of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque by MRI in a rabbit model. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:323–32.

Mohler ER, Sarov-Blat L, Shi Y, Hamamdzic D, Zalewski A, Macphee C, et al. Site-specific atherogenic gene expression correlates with subsequent variable lesion development in coronary and peripheral vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:850–5.

Gerrity RG, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Kimsey T. Diabetes-induced accelerated atherosclerosis in swine. Diabetes. 2001;50:1654–65.

Hamada N, Miyata M, Eto H, Shirasawa T, Akasaki Y, Nagaki A, et al. Tacrolimus-eluting stent inhibits neointimal hyperplasia via calcineurin/NFAT signaling in porcine coronary artery model. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:97–103.

Lederman RJ, Raylman RR, Fisher SJ, Kison PV, San H, Nabel EG, et al. Detection of atherosclerosis using a novel positron-sensitive probe and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22:747–53.

Aziz K, Berger K, Claycombe K, Huang R, Patel R, Abela GS. Noninvasive detection and localization of vulnerable plaque and arterial thrombosis with computed tomography angiography/positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2008;117:2061–70.

Ogawa M, Magata Y, Kato T, Hatano K, Ishino S, Mukai T, et al. Application of 18F-FDG PET for monitoring the therapeutic effect of antiinflammatory drugs on stabilization of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1845–50.

Laitinen I, Marjamäki P, Haaparanta M, Savisto N, Laine VJO, Soini SL, et al. Non-specific binding of [18F]FDG to calcifications in atherosclerotic plaques: experimental study of mouse and human arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1461–7.

Matter CM, Wyss MT, Meier P, Späth N, Lukowicz von T, Lohmann C, et al. 18F-choline images murine atherosclerotic plaques ex vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:584–9.

Wagner S, Breyholz H-J, Law MP, Faust A, Höltke C, Schröer S, et al. Novel fluorinated derivatives of the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors N-hydroxy-2(R)-[[(4-methoxyphenyl)sulfonyl](benzyl)- and (3-picolyl)-amino]-3-methyl-butanamide as potential tools for the molecular imaging of activated MMPs with PET. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5752–64.

Breyholz HJ, Wagner S, Levkau B, Schober O, Schäfers M, Kopka K. A 18F-radiolabeled analogue of CGS 27023A as a potential agent for assessment of matrix-metalloproteinase activity in vivo. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;51:24–32.

Schulz C, Penz S, Hoffmann C, Langer H, Gillitzer A, Schneider S, et al. Platelet GPVI binds to collagenous structures in the core region of human atheromatous plaque and is critical for atheroprogression in vivo. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:356–67.

Yun M, Yeh D, Araujo LI, Jang S, Newberg A, Alavi A. F-18 FDG uptake in the large arteries: a new observation. Clin Nucl Med. 2001;26:314–9.

Tatsumi M, Cohade C, Nakamoto Y, Wahl RL. Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the aortic wall at PET/CT: possible finding for active atherosclerosis. Radiology. 2003;229:831–7.

Tahara N, Kai H, Yamagishi S-I, Mizoguchi M, Nakaura H, Ishibashi M, et al. Vascular inflammation evaluated by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is associated with the metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1533–9.

Rudd JHF, Hyafil F, Fayad ZA. Inflammation imaging in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1009–16.

Rudd JHF, Warburton EA, Fryer TD, Jones HA, Clark JC, Antoun N, et al. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation with [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2002;105:2708–11.

Rudd JHF, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Rafique A, Farkouh M, et al. (18)Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging of atherosclerotic plaque inflammation is highly reproducible: implications for atherosclerosis therapy trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:892–6.

Davies JR, Rudd JHF, Fryer TD, Graves MJ, Clark JC, Kirkpatrick PJ, et al. Identification of culprit lesions after transient ischemic attack by combined 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography and high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 2005;36:2642–7.

Rudd JHF, Myers KS, Bansilal S, Machac J, Pinto CA, Tong C, et al. Atherosclerosis inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET: carotid, iliac, and femoral uptake reproducibility, quantification methods, and recommendations. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:871–8.

Ogawa M, Ishino S, Mukai T, Asano D, Teramoto N, Watabe H, et al. (18)F-FDG accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques: immunohistochemical and PET imaging study. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1245–50.

Tawakol A, Migrino RQ, Bashian GG, Bedri S, Vermylen D, Cury RC, et al. In vivo 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging provides a noninvasive measure of carotid plaque inflammation in patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1818–24.

Paulmier B, Duet M, Khayat R, Pierquet-Ghazzar N, Laissy J-P, Maunoury C, et al. Arterial wall uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose on PET imaging in stable cancer disease patients indicates higher risk for cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15:209–17.

Izquierdo-Garcia D, Davies JR, Graves MJ, Rudd JHF, Gillard JH, Weissberg PL, et al. Comparison of methods for magnetic resonance-guided [18-F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in human carotid arteries: reproducibility, partial volume correction, and correlation between methods. Stroke. 2009;40:86–93.

Rinnab L, Simon J, Hautmann RE, Cronauer MV, Hohl K, Buck AK, et al. [(11)C]choline PET/CT in prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2009;27:619–25.

Yoshimoto M, Waki A, Obata A, Furukawa T, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Radiolabeled choline as a proliferation marker: comparison with radiolabeled acetate. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:859–65.

Boggs KP, Rock CO, Jackowski S. Lysophosphatidylcholine and 1-O-octadecyl-2-O-methyl-rac-glycero-3-phosphocholine inhibit the CDP-choline pathway of phosphatidylcholine synthesis at the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase step. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7757–64.

Ramirez de Molina A, Gutiérrez R, Ramos MA, Silva JM, Silva J, Bonilla F, et al. Increased choline kinase activity in human breast carcinomas: clinical evidence for a potential novel antitumor strategy. Oncogene. 2002;21:4317–22.

Wyss MT, Weber B, Honer M, Späth N, Ametamey SM, Westera G, et al. 18F-choline in experimental soft tissue infection assessed with autoradiography and high-resolution PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:312–6.

Spaeth N, Wyss MT, Weber B, Scheidegger S, Lutz A, Verwey J, et al. Uptake of 18F-fluorocholine, 18F-fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine, and 18F-FDG in acute cerebral radiation injury in the rat: implications for separation of radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1931–8.

Bucerius J, Schmaljohann J, Böhm I, Palmedo H, Guhlke S, Tiemann K, et al. Feasibility of 18F-fluoromethylcholine PET/CT for imaging of vessel wall alterations in humans – first results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:815–20.

Kato K, Schober O, Ikeda M, Schäfers M, Ishigaki T, Kies P, et al. Evaluation and comparison of 11C-choline uptake and calcification in aortic and common carotid arterial walls with combined PET/CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1622–8.

Förster S, Rominger A, Saam T, Wolpers S, Nikolaou K, Cumming P, et al. 18F-fluoroethylcholine uptake in arterial vessel walls and cardiovascular risk factors: correlation in a PET-CT study. Nuklearmedizin. 2010;49:148–53.

Vöö S, Kwee RM, Sluimer JC, Schreuder FH, Wierts R, Bauwens M, et al. Imaging Intraplaque inflammation in carotid atherosclerosis with 18F-Fluorocholine positron emission tomography-computed tomography: prospective study on vulnerable atheroma with Immunohistochemical validation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016:9(5). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.004467.

Armani C, Catalani E, Balbarini A, Bagnoli P, Cervia D. Expression, pharmacology, and functional role of somatostatin receptor subtypes 1 and 2 in human macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:845–55.

Breeman WAP, de Jong M, de Blois E, Bernard BF, Konijnenberg M, Krenning EP. Radiolabelling DOTA-peptides with 68Ga. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:478–85.

Rominger A, Saam T, Vogl E, Übleis C, la Fougère C, Förster S, et al. In vivo imaging of macrophage activity in the coronary arteries using 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT: correlation with coronary calcium burden and risk factors. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:193–7.

Li X, Samnick S, Lapa C, Israel I, Buck AK, Kreissl MC, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for the detection of inflammation of large arteries: correlation with18F-FDG, calcium burden and risk factors. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:52.

Tarkin JM, Joshi FR, Evans NR, Chowdhury MM, Figg NL, Shah AV, et al. Detection of atherosclerotic inflammation by 68Ga-DOTATATE PET compared to [18F]FDG PET imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1774–91.

Pedersen SF, Sandholt BV, Keller SH, Hansen AE, Clemmensen AE, Sillesen H, et al. 64Cu-DOTATATE PET/MRI for detection of activated macrophages in carotid atherosclerotic plaques: studies in patients undergoing endarterectomy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1696–703.

Derlin T, Richter U, Bannas P, Begemann P, Buchert R, Mester J, et al. Feasibility of 18F-sodium fluoride PET/CT for imaging of atherosclerotic plaque. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:862–5.

Derlin T, Tóth Z, Papp L, Wisotzki C, Apostolova I, Habermann CR, et al. Correlation of inflammation assessed by 18F-FDG PET, active mineral deposition assessed by 18F-fluoride PET, and vascular calcification in atherosclerotic plaque: a dual-tracer PET/CT study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1020–7.

Joshi NV, Vesey AT, Williams MC, Shah ASV, Calvert PA, Craighead FH, et al. 18F-fluoride positron emission tomography for identification of ruptured and high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques: a prospective clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383:705–13.

Irkle A, Vesey AT, Lewis DY, Skepper JN, Bird JLE, Dweck MR, et al. Identifying active vascular microcalcification by (18)F-sodium fluoride positron emission tomography. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7495.

Fiz F, Morbelli S, Piccardo A, Bauckneht M, Ferrarazzo G, Pestarino E, et al. 18F-NaF uptake by atherosclerotic plaque on PET/CT imaging: inverse correlation between calcification density and mineral metabolic activity. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1019–23.

Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. Labeling proteins with fluorine-18 using N-succinimidyl 4-[18F]fluorobenzoate. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1992;19:275–81.

Hultsch C, Schottelius M, Auernheimer J, Alke A, Wester H-J. (18)F-Fluoroglucosylation of peptides, exemplified on cyclo(RGDfK). Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1469–74.

Marik J, Hausner SH, Fix LA, Gagnon MKJ, Sutcliffe JL. Solid-phase synthesis of 2-[18F]fluoropropionyl peptides. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1017–21.

Ramenda T, Kniess T, Bergmann R, Steinbach J, Wuest F. Radiolabelling of proteins with fluorine-18 via click chemistry. Chem Commun (Camb). 2009;(48):7521–3.

Glaser M, Arstad E. “Click labeling” with 2-[18f]fluoroethylazide for positron emission tomography. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:989–93.

Thonon D, Kech C, Paris J, Lemaire C, Luxen A. New strategy for the preparation of clickable peptides and labeling with 1-(azidomethyl)-4-[(18)F]-fluorobenzene for PET. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:817–23.

Maschauer S, Einsiedel J, Haubner R, Hocke C, Ocker M, Hübner H, et al. Labeling and glycosylation of peptides using click chemistry: a general approach to (18)F-glycopeptides as effective imaging probes for positron emission tomography. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010:49:976–9.

Li Y, Liu Z, Harwig CW, Pourghiasian M, Lau J, Lin K-S, et al. 18F-click labeling of a bombesin antagonist with an alkyne-18F-ArBF3−: in vivo PET imaging of tumors expressing the GRP-receptor. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3:57–70.

Arumugam S, Chin J, Schirrmacher R, Popik VV, Kostikov AP. [18F]azadibenzocyclooctyne ([18F]ADIBO): a biocompatible radioactive labeling synthon for peptides using catalyst free [3+2] cycloaddition. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:6987–91.

Hausner SH, Bauer N, Sutcliffe JL. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the effects of aluminum [18F]fluoride radiolabeling on an integrin αvβ6-specific peptide. Nucl Med Biol. 2014;41:43–50.

Campbell-Verduyn LS, Mirfeizi L, Schoonen AK, Dierckx RA, Elsinga PH, Feringa BL. Strain-promoted copper-free “click” chemistry for 18F radiolabeling of bombesin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:11117–20.

Selvaraj R, Liu S, Hassink M, Huang C-W, Yap L-P, Park R, et al. Tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene ligation for the rapid construction of integrin αvβ3 targeted PET tracer based on a cyclic RGD peptide. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5011–4.

Knight JC, Richter S, Wuest M, Way JD, Wuest F. Synthesis and evaluation of an 18F-labelled norbornene derivative for copper-free click chemistry reactions. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:3817–25.

Mu L, Höhne A, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, Cyr JE, et al. Silicon-based building blocks for one-step 18F-radiolabeling of peptides for PET imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:4922–5.

Höhne A, Mu L, Honer M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, et al. Synthesis, 18F-labeling, and in vitro and in vivo studies of bombesin peptides modified with silicon-based building blocks. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1871–9.

Rosa-Neto P, Wängler B, Iovkova L, Boening G, Reader A, Jurkschat K, et al. [18F]SiFA-isothiocyanate: a new highly effective radioactive labeling agent for lysine-containing proteins. Chembiochem. 2009;10:1321–4.

Wängler B, Quandt G, Iovkova L, Schirrmacher E, Wängler C, Boening G, et al. Kit-like 18F-labeling of proteins: synthesis of 4-(di-tert-butyl[18F]fluorosilyl)benzenethiol (Si[18F]FA-SH) labeled rat serum albumin for blood pool imaging with PET. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:317–21.

Ting R, Harwig C, auf dem Keller U, McCormick S, Austin P, Overall CM, et al. Toward [18F]-labeled aryltrifluoroborate radiotracers: in vivo positron emission tomography imaging of stable aryltrifluoroborate clearance in mice. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12045–55.

Liu Z, Pourghiasian M, Radtke MA, Lau J, Pan J, Dias GM, et al. An organotrifluoroborate for broadly applicable one-step 18F-labeling. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:11876–80.

Liu Z, Radtke MA, Wong MQ, Lin K-S, Yapp DT, Perrin DM. Dual mode fluorescent (18)F-PET tracers: efficient modular synthesis of rhodamine-[cRGD]2-[(18)F]-organotrifluoroborate, rapid, and high yielding one-step (18)F-labeling at high specific activity, and correlated in vivo PET imaging and ex vivo fluorescence. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:1951–62.

Studenov AR, Adam MJ, Wilson JS, Ruth TJ. New radiolabelling chemistry: synthesis of phosphorus–[18F]fluorine compounds. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2005;48:497–500.

McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, D'Souza CA, Rossi EA, Laverman P, et al. A novel method of 18F radiolabeling for PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:991–8.

Laverman P, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Goldenberg DM, Boerman OC. Al(18)F labeling of peptides and proteins. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2014;57:219–23.

Blau M, Ganatra R, Bender MA. 18F-Fluoride for bone imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 1972;2:31–7.

Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SB. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science. 1994;266:776–9.

Hackeng TM, Griffin JH, Dawson PE. Protein synthesis by native chemical ligation: expanded scope by using straightforward methodology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10068–73.

Dirksen A, Langereis S, de Waal BFM, van Genderen MHP, Meijer EW, de Lussanet QG, et al. Design and synthesis of a bimodal target-specific contrast agent for angiogenesis. Org Lett. 2004;6:4857–60.

Van de Vijver P, Suylen D, Dirksen A, Dawson PE, Hackeng TM. Nepsilon-(thiaprolyl)-lysine as a handle for site-specific protein conjugation. Biopolymers. 2010;94:465–74.

Dirksen A, Hackeng TM, Dawson PE. Nucleophilic catalysis of oxime ligation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7581–4.

Kalia J, Raines RT. Hydrolytic stability of hydrazones and oximes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:7523–6.

Agten SM, Suylen D, Ippel H, Kokozidou M, Tans G, Van de Vijver P, et al. Chemoselective oxime reactions in proteins and peptides by using an optimized oxime strategy: the demise of levulinic acid. Chembiochem. 2013;14:2431–4.

Schurgers LJ, Cranenburg ECM, Vermeer C. Matrix Gla-protein: the calcification inhibitor in need of vitamin K. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:593–603.

Schurgers LJ, Spronk HMH, Skepper JN, Hackeng TM, Shanahan CM, Vermeer C, et al. Post-translational modifications regulate matrix Gla protein function: importance for inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2503–11.

Yao Y, Bennett BJ, Wang X, Rosenfeld ME, Giachelli C, Lusis AJ, et al. Inhibition of bone morphogenetic proteins protects against atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2010;107:485–94.

Schurgers LJ, Teunissen KJF, Knapen MHJ, Kwaijtaal M, van Diest R, Appels A, et al. Novel conformation-specific antibodies against matrix gamma-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) protein: undercarboxylated matrix Gla protein as marker for vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1629–33.

Bostrom K, Watson K, Horn S, Wortham C, Herman I, Demer L. Bone morphogenetic protein expression in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1800–9.

Bostrom K, Watson K, Stanford W, Demer L. Atherosclerotic calcification: relation to developmental osteogenesis. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:88B–91B.

Flammer AJ, Gössl M, Widmer RJ, Reriani M, Lennon R, Loeffler D, et al. Osteocalcin positive CD133+/CD34-/KDR+ progenitor cells as an independent marker for unstable atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2963–9.

van de Loo P, Soute B, van Haarlem L, Vermeer C. The effect of Gla-containing proteins on the precipitation of insoluble salts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;142:113–9.

Dhore CR, Cleutjens JP, Lutgens E, Cleutjens KB, Geusens PP, Kitslaar PJ, et al. Differential expression of bone matrix regulatory proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1998–2003.

Funding

Jan Bucerius, Felix M. Mottaghy and Leon Schurgers are in part funded via theEuropean Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 722609.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Studies with human participants or animals

This article does not describe any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions