Abstract

Objective

Examine the 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI imaging characteristics of chordoma.

Materials and methods

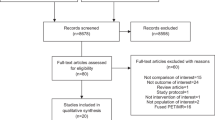

Biopsy-proven chordoma with a pre-therapy 18F-FDG PET/CT from 2001 through 2019 in patients > 18 years old were retrospectively reviewed. Multiple PET/CT and MRI imaging parameters were assessed.

Results

A total of 23 chordoma patients were included (16 M, 7 F; average age of 60.1 ± 13.0 years) with comparative MRI available in 22 cases. This included 13 sacrococcygeal, 9 mobile spine, and one clival lesions. On 18F-FDG PET/CT, chordomas demonstrated an average SUVmax of 5.8 ± 3.7, average metabolic tumor volume (MTV) of 160.2 ± 263.8 cm3, and average total lesion glycolysis (TLG) of 542.6 ± 1210 g. All demonstrated heterogeneous FDG activity. On MRI, chordomas were predominantly T2 hyperintense (22/22) and T1 isointense (18/22), contained small foci of T1 hyperintensity (17/22), and demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement (14/20). There were no statistically significant associations found between 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI imaging features. There was no relationship of SUVmax (p = 0.53), MTV (p = 0.47), TLG (p = 0.48), maximal dimension (p = 0.92), or volume (p = 0.45) to the development of recurrent or metastatic disease which occurred in 6/22 patients over a mean follow-up duration of 4.1 ± 2.0 years.

Conclusion

On 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, chordomas demonstrate moderate, heterogeneous FDG uptake. Predominant T2 hyperintensity and small foci of internal increased T1 signal are common on MRI. The inherent FDG avidity of chordomas suggests that 18F-FDG PET/CT may be a useful modality for staging, evaluating treatment response, and assessing for recurrent or metastatic disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Yamaguchi T, et al. Benign notochordal cell tumors: a comparative histological study of benign notochordal cell tumors, classic chordomas, and notochordal vestiges of fetal intervertebral discs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(6):756–61.

Bjornsson J, et al. Chordoma of the mobile spine. A clinicopathologic analysis of 40 patients. Cancer. 1993;71(3):735–40.

Meyer JE, et al. Chordomas: their CT appearance in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine. Radiology. 1984;153(3):693–6.

Unni KK, Inwards CY. Dahlin’s bone tumors: general aspects and data on 10,165 cases. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkin; 2010.

Gerber S, et al. Imaging of sacral tumours. Skelet Radiol. 2008;37(4):277–89.

Stacchiotti S, Sommer J. Building a global consensus approach to chordoma: a position paper from the medical and patient community. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):e71–83.

McPherson CM, et al. Metastatic disease from spinal chordoma: a 10-year experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5(4):277–80.

Young VA, et al. Characteristics and patterns of metastatic disease from chordoma. Sarcoma. 2015;2015:517657.

Suga K, et al. F-18 FDG PET/CT monitoring of radiation therapeutic effect in hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34(3):199–202.

Sung MS, et al. Sacrococcygeal chordoma: MR imaging in 30 patients. Skelet Radiol. 2005;34(2):87–94.

Smolders D, et al. Value of MRI in the diagnosis of non-clival, non-sacral chordoma. Skelet Radiol. 2003;32(6):343–50.

Murphey MD, et al. From the archives of the AFIP. Primary tumors of the spine: radiologic pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1996;16(5):1131–58.

Cui J-F, et al. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging features of cervical chordoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;16(1):861–5.

Si M-J, et al. Differentiation of primary chordoma, giant cell tumor and schwannoma of the sacrum by CT and MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(12):2309–15.

Lin CY, et al. Chordoma detected on F-18 FDG PET. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31(8):506–7.

Park SA, Kim HS. F-18 FDG PET/CT evaluation of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33(12):906–8.

Cui F, et al. Humeral metastasis of sacrococcygeal chordoma detected by fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography: a case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(2):449–52.

Ochoa-Figueroa MA, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET-CT in the study of sacrococcygeal chordoma. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2012;31(6):359–61.

Derlin T, Sohns JM, Hueper K. 68Ga-DOTA-TATE PET/CT for molecular imaging of somatostatin receptor expression in metastasizing chordoma: comparison with 18F-FDG. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42(4):e210–1.

Miyazawa N, et al. Thoracic chordoma: review and role of FDG-PET. J Neurosurg Sci. 2008;52(4):117–21 discussion 121-2.

Sridhar P, et al. FDG PET metabolic tumor volume segmentation and pathologic volume of primary human solid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(5):1114–9.

Werner-Wasik M, et al. What is the best way to contour lung tumors on PET scans? Multiobserver validation of a gradient-based method using a NSCLC digital PET phantom. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):1164–71.

Obara P, et al. Quantification of metabolic tumor activity and burden in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: is manual adjustment of semiautomatic gradient-based measurements necessary? Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36(8):782–9.

Stacchiotti S, et al. Phase II study of imatinib in advanced chordoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(9):914–20.

Darby AJ, et al. Vertebral intra-osseous chordoma or giant notochordal rest? Skelet Radiol. 1999;28(6):342–6.

Yamaguchi T, et al. Distinguishing benign notochordal cell tumors from vertebral chordoma. Skelet Radiol. 2008;37(4):291–9.

Kyriakos M. Benign notochordal lesions of the axial skeleton: a review and current appraisal. Skelet Radiol. 2011;40(9):1141–52.

Kreshak J, et al. Difficulty distinguishing benign notochordal cell tumor from chordoma further suggests a link between them. Cancer Imaging. 2014;14(1):4–4.

Chambers PW, Schwinn CP. Chordoma. A clinicopathologic study of metastasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;72(5):765–76.

Chang C, et al. Osseous metastases of chordoma: imaging and clinical findings. Skelet Radiol. 2017;46(3):351–8.

Delank KS, et al. Metastasizing chordoma of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(2):167–71.

Kishimoto R, et al. Imaging characteristics of metastatic chordoma. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30(6):509–16.

Rohatgi S, et al. Metastatic Chordoma: report of the two cases and review of the literature. Eurasian J Med. 2015;47(2):151–4.

Houdek MT, et al. Low dose radiotherapy is associated with local complications but not disease control in sacral chordoma. J Surg Oncol. 2019;119(7):856–63.

Di Maio S, et al. Novel targeted therapies in chordoma: an update. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015;11:873–83.

Hindi N, et al. Imatinib in advanced chordoma: a retrospective case series analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(17):2609–14.

Schulz-Ertner D, et al. Effectiveness of carbon ion radiotherapy in the treatment of skull-base chordomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68(2):449–57.

Chetan MR, et al. Role of diffusion-weighted imaging in monitoring treatment response following high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation of recurrent sacral chordoma. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(10):1197–201.

Santos P, et al. T1-weighted dynamic contrast-enhanced MR perfusion imaging characterizes tumor response to radiation therapy in chordoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(11):2210–6.

Afaq A, Andreou A, Koh DM. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for tumour response assessment: why, when and how? Cancer Imaging. 2010;10(1A):S179–88.

Preda L, et al. Predictive role of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) from diffusion weighted MRI in patients with sacral chordoma treated with carbon ion radiotherapy (CIRT) alone. Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108933.

Roth C, et al. Simultaneous F18-FDG-PET/MR optimized treatment planning in a young patient with sacro-coccygeal chordoma. Klin Padiatr. 2018;230(6):326–7.

Rakheja R, et al. Correlating metabolic activity on 18F-FDG PET/CT with histopathologic characteristics of osseous and soft-tissue sarcomas: a retrospective review of 136 patients. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):1409–16.

Bastiaannet E, et al. The value of FDG-PET in the detection, grading and response to therapy of soft tissue and bone sarcomas; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(1):83–101.

Lim HJ, et al. Utility of positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging in the evaluation of sarcomas: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;143:1–13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statement of informed consent

The need for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Olson, J.T., Wenger, D.E., Rose, P.S. et al. Chordoma: 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI imaging features. Skeletal Radiol 50, 1657–1666 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-021-03723-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-021-03723-w