Abstract

Cystinuria is a genetic disorder caused by defects in the b0,+ transporter system, which is composed of rBAT and b0,+AT coded by SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, respectively. Variants in SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 follow autosomal recessive inheritance and autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance, respectively, which complicates the interpretation of cystinuria-related variants. Here, we report seven different SLC3A1 variants and six different SLC7A9 variants. Among these variants were two novel variants previously not reported: SLC3A1 c.223C > T and SLC7A9 c.404A > G. In silico analysis using REVEL correlated well with the functional loss upon SLC7A9 variants with scores of 0.8560–0.9200 and 0.4970–0.5239 for severe and mild decrease in transport activity, respectively. In addition, DynaMut2 was able to predict a decreased protein expression level resulting from the SLC7A9 variant c.313G > A with a ΔΔGStability −2.93 kcal/mol. Our study adds to the literature as additional cases of a variant allow applying the PM3 criterion with higher strength level. In addition, we suggest the clinical utility of REVEL and DynaMut2 in interpreting SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 variants. While a decreased protein expression level is not embraced in the current variant interpretation guidelines, we believe in silico protein stability predicting tools could serve as evidence of protein function loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cystinuria (OMIM: 220,100) is a genetic disorder caused by defects in the dibasic amino acid transporters, which results in elevated urinary cystine along with dibasic amino acids such as arginine, ornithine, and lysine [1]. Cystinuria has traditionally been classified into three categories based on the level of urinary amino acid excretion. Following identification of the underlying genetic cause, the disorder is now labeled type A and B for variants in SLC3A1 (OMIM: 104,614) and SLC7A9 (OMIM: 604,144), respectively [2].

The b0,+ system is composed of rBAT and b0,+AT coded by SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, respectively, which form a heterodimer with a disulfide bond [3, 4]. While the b0,+AT subunit transports the amino acids, the rBAT subunit plays a role in trafficking and maturation of the complex [4,5,6]. The inheritance pattern of cystinuria-related variants also shows a distinct pattern. Variants in SLC3A1 are inherited in an autosomal recessive order, whereas those in SLC7A9 follow an autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance pattern. This paradigm seems obvious considering the function of proteins encoded by each gene per se.

While a number of variants have been discovered as a cause of cystinuria, interpretation of variants in SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 is still challenging. First, the inheritance pattern complicates the interpretation. In the autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance pattern, it is difficult to determine the pathogenicity when there are two variants of uncertain significance in one gene as either or both variants could contribute to the disease. Second, genetic heterogeneity of cystinuria is another concern. When there are variants of question in both SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, it is not straightforward to ascertain which variant is causative. Moreover, there are cystinuria patients without any pathogenic variants in SLC3A1 and SLC7A9. As it is currently suspected there could be other genes associated with cystinuria [7], relating a novel variant in SLC3A1 and/or SLC7A9 with cystinuria is challenging.

In this study, we report ten cystinuria cases, which include two novel variants. We believe the current study will serve as evidence in interpreting SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 variants. Furthermore, while protein stability is an attribute not employed in the current guidelines for variant interpretation, we have evaluated protein stability change caused by variants to unveil its potential utility in determining the pathogenicity of a given variant.

Methods

Study population

As the aim of this study was to investigate genetic variants in cystinuria patients, those with SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 sequencing orders were included. Additional clinical information of the enrolled cystinuria patients were obtained, which included age of onset, familial history of urolithiasis, clinical manifestation, intervention, chemical composition of the urinary stone, urine amino acid levels, and identified genetic variants of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2022–05-064), and the need for written informed consent was wived due to the anonymous and retrospective nature of this study.

Laboratory analyses

Urine amino acid levels were quantitatively measured with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) to reveal changes in urinary dibasic amino acid levels including cystine. After urologic intervention of each patient, urinary stone analysis was performed to examine the chemical composition through Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) using the FT-IR system 2000 (PerkinElmer, Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland) and Spectrum software (PerkinElmer) described in a previous publication [8]. For genetic analysis, DNA was extracted from whole blood using a Roche MagNA Pure 96 DNA isolation kit (Roche Applied Science, Manheim, Germany). The SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 gene sequences were obtained with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and full sequencing using an ABI Prism 3730XL DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The in-house designed primers are available upon reasonable request. Nucleotides were numbered according to the transcript sequences of SLC3A1 (NM_000341.3) and SLC7A9 (NM_014270.4).

Evaluation of SLC7A9 variants with known functional changes

As there was one previous study demonstrating the functional change in SLC7A9 variants experimentally [9], we evaluated the feasibility of using the pathogenicity score of REVEL [10] and predicted stability change (ΔΔGStability) calculated with DynaMut2 [11].

Variant interpretation

The identified variants were interpreted applying the ACGS Best Practice Guidelines for Variant Classification 2019 [12], which is based on the 2015 ACMG/AMP guidelines [13]. In addition, variants with one very strong criterion along with one supporting criterion were regarded as likely pathogenic according to the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Recommendation for PM2 [14]. The PM3 criterion was applied following the guidance of ClinGen SVI recommendation, which allows for applying different strength levels based on the phasing of two variants and classification of the variant other than the variant of interest [15]. The PM1_Supporting criterion was assigned if a variant was predicted to affect protein function according to Martell et al. (2017) [16]. For investigation of previous literature of a certain variant, HGMD Professional (2022.1) [17] and Mastermind [18] were utilized. To analyze the population frequency, gnomAD v2.1.1 [19] and KRGDB_1722 [20] were used. For in silico prediction, REVEL [10] and SpliceAI [21] were utilized for single nucleotide variants and splice site variants, respectively. Predicted stability change (ΔΔGStability) was calculated with DynaMut2 [11]. For novel missense variants, the structure of the resulting protein was illustrated using Missense3D [22].

Using DynaMut2 to predict protein instability

DynaMut2 is an in silico tool designed to predict a change in protein stability upon missense variants [11]. The authors of the DynaMut2 claim its usefulness in predicting the role of variants in disease [11]. The predicted stability change (ΔΔGStability) values were obtained with DynaMut2 where negative values indicate a destabilizing effect and positive values indicate a stabilizing effect. The greater the absolute value of ΔΔGStability, the greater the effect. The ΔΔGStability values were classified into seven categories: highly destabilizing (ΔΔGStability < −1.84 kcal/mol), destabilizing (−1.84 kcal/mol < ΔΔGStability < −0.92 kcal/mol), slightly destabilizing (−0.92 kcal/mol < ΔΔGStability < −0.46 kcal/mol), neutral (−0.46 kcal/mol < ΔΔGStability < 0.46 kcal/mol), slightly stabilizing (0.46 kcal/mol < ΔΔGStability < 0.92 kcal/mol), stabilizing (0.92 kcal/mol < ΔΔGStability < 1.84 kcal/mol), and highly stabilizing (ΔΔGStability > 1.84 kcal/mol). The PDB accession number 6LID [23] was used as the reference structure of the b0,+AT-rBAT complex. Since the b0,+AT-rBAT complex is a dimer of heterodimers consisting of b0,+AT and rBAT, the ΔΔGStability both when one dimer was affected and when both dimers were affected were calculated.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the cystinuria patients are summarized in Table 1. While all patients had multiple events of urolithiasis, only two patients had a familial history of urolithiasis. The identified variants, stone component, and urine amino acid levels are listed in Table 2. Stones from all patients consisted of 100% cystine. Increased urinary cystine and dibasic amino acid levels were noted in all patients that were tested.

Evaluation of REVEL and DynaMut2 in predicting the degree of functional change

The REVEL score was able to distinguish variants with mild effect and severe effect in transport activity as all variants with a mild decrease in protein function had a REVEL score less than 0.6, while other variants with severe loss of function all had a REVEL score greater than 0.8. Among the evaluated variants, the p.(Gly105Arg) variant exhibited a significantly decreased protein expression by 10% of wild-type in transfected cells [9], which was also the only variant predicted to be highly destabilizing according to the DynaMut2 results with a ΔΔGStability of −2.93 kcal/mol when both SLC7A9 light chains of the dimer were composed of proteins with the p.(Gly105Arg) variant (Table 3). Variants other than p.(Gly105Arg) did not have a drastic effect on ΔΔGStability, with the maximum effect being −1.65 kcal/mol by p.(Ala70Val) indicating a destabilizing effect.

Interpretation and classification of the identified variants

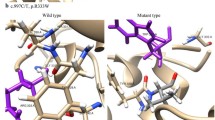

A total of 13 different variants were identified with seven different SLC3A1 variants and six different SLC7A9 variants including one novel SLC3A1 variant and one novel SLC7A9 variant not previously reported. Among the SLC3A1 variants were three pathogenic variants, three likely pathogenic variants, and one variant of uncertain significance. Among the SLC7A9 variants were one pathogenic variant, two likely pathogenic variants, and three variants of uncertain significance. While all variants identified in our study had an extremely low minor allele frequency in the gnomAD v2.1.1, NM_014270.4(SLC7A9):c.829G > A had a MAF of 0.6407% in KRGDB_1722. This variant also had the highest MAF in the gnomAD v2.1.1. among the variants identified in this study. In silico prediction of missense variants with REVEL resulted in (1) a score ≥ 0.8 for three SLC3A1 variants and two SLC7A9 variants, (2) 0.6 ≤ score < 0.8 for three SLC7A9 variants, and (3) a score < 0.6 for one SLC3A1 variant. SpliceAI predicted donor loss (score 1.00 at −1 bp) and gain (score 0.67 at 44 bp) in the c.1500 + 1G > A variant. All other variants identified in our patients were predicted to have no splicing effect according to SpliceAI. DynaMut2 predicted that all SLC3A1 missense variants will cause a highly destabilizing effect when both chains of the dimer are affected and the p.(Tyr135Cys) variant of SLC7A9 will cause a highly destabilizing effect even with one of the dimers affected. There were two novel variants identified: (1) NM_000341.3(SLC3A1):c.223C > T and (2) NM_014270.4(SLC7A9):c.404A > G. A novel pathogenic variant was identified in SLC3A1, whereas a novel variant of uncertain significance was identified from SLC7A9. Using Missense3D, it was predicted that the novel p.(Tyr135Cys) variant of SLC7A9, located at the end of the transmembrane helix, does not change the secondary structure of the protein (Fig. 1). In addition, the p.(Trp440Arg) variant of SLC3A1 was interpreted as a likely pathogenic variant with the support of a case included in our study, which elevates the evidence level of the PM3 criterion. Refer to Table 4 for the list of variants, their interpretation, and related information; refer to Table 5 for details regarding the PM3 criterion. For further evaluation of the effects of compound heterozygote variants, the protein stability change affected by two variants was also predicted, which demonstrated that c.418G > A(;)1976A > C and c.1976A > C(;)2017 T > C would have highly destabilizing effects (Table 6).

Discussion

Since the discovery of the underlying genetic defects in cystinuria, a number of variants in SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 have been reported to cause cystinuria. However, interpretation of cystinuria-related variants is still challenging for several reasons. Molecular variants in the b0,+ transport system are known to cause cystinuria by various functional defects including trafficking, protein folding, protein expression, and amino acid transport [24]. While the current guidelines for variant interpretation embrace the decrease in protein expression by assigning evidence for null variants with consideration of the nonsense-mediated decay mechanism, the degradation of a translated protein due to instability is still underappreciated.

In this study, we reviewed the SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 variants identified from cystinuria patients of our institute, which revealed novel variants not reported to date as well as reclassified a previously reported variant of uncertain significance as a likely pathogenic variant. In addition, the results of our evaluation suggest the utility of REVEL in predicting the functional change of the transporter system. However, while REVEL demonstrated different scores for SLC7A9 variants with mild functional defect (score < 0.6) and severe functional loss (score ≥ 0.8), we were unable to establish a definitive cutoff for REVEL due to limited functional studies with no variants with the degree of functional change elucidated falling into the grey zone (0.6 ≤ score < 0.8). In addition, there were no available functional studies for the SLC3A1 variants. The protein stability change estimated with DynaMut2 correlated well with the decrease in protein expression level resulting from the p.(Gly105Arg) variant of SLC7A9. Among the variants of uncertain significance identified in our study were two variants (SLC3A1 p.(Gln659Pro) and SLC7A9 p.(Tyr135Cys)) predicted by DynaMut2 to result in a highly destabilizing protein. We suspect that these variants favor pathogenicity despite insufficient evidence according to the current guidelines. Although DynaMut2 correlated well with the significantly reduced protein expression of SLC7A9 p.(Gly105Arg), interpretation of the predicted protein instability should be done cautiously since most protein stability prediction tools including DynaMut2 tend to have a bias toward destabilization [25]. As none of the patients with two different variants had a familial history of urolithiasis, the most likely scenario is that both variants in a patient predispose to cystinuria and each of the variants was inherited from a different parent.

Although in silico tools serve as a powerful resource in predicting the pathogenicity of a variant, there are times when the evidence is not sufficient to classify a variant as pathogenic or likely pathogenic despite the variant being highly suspicious as the cause of cystinuria considering other information and the criteria assigned. While some variants are still classified as a variant of uncertain significance despite being highly suspected for pathogenicity, this report adds to the literature and will hopefully be utilized as further evidence for assigning any pathogenic criteria and aid further reports of these variants. Criteria such as PS4 and PM3 could be applied with different weight depending on the number of reported cases.

The diversity of cystinuria-related variants has been reported to be different depending on the ethnic group. While the variant spectrum is unknown regarding the Korean population, it is of note that the variants identified in this study showed a different pattern from a previous Korean publication that included seven cystinuria patients with genetic studies conducted [1].

There are several limitations to our study. First, three patients in our study lacked SLC7A9 sequencing results as the previous workflow of our institute was to order SLC7A9 sequencing if no variants were identified from SLC3A1. However, two patients carried homozygous likely pathogenic variants in SLC3A1, and one patient carried a pathogenic variant and a variant of uncertain significance in SLC3A1. As the variant of uncertain significance was deficient of one supporting evidence from being classified as a likely pathogenic variant, we suggest that cystinuria in all three cases could be explained with the variants identified in SLC3A1. Second, genetic tests of family members were not carried out. As the designation of phase in patients harboring two different mutations would allow applying stronger evidence in the PM3 criterion, the lack of familial data limits the variant interpretation. Moreover, family members carrying one of the two variants identified in the proband would provide a more sophisticated genotype–phenotype correlation. Third, urinary amino acid levels were measured during the course of treatment. Since the measured concentrations are from different stages of the disease, the data could not be used for genotype–phenotype correlation of the disease.

In summary, we report ten cystinuria cases and the interpretation of variants identified in SLC3A1 and SLC7A9, which included a novel variant in each gene. Our study implies the significance of reporting variants and literature review in determining the pathogenicity of a variant. Moreover, we suggest the potential role of protein stability in predicting loss of function caused by a decrease in protein expression. Hence, this study would benefit future variant interpretation by serving as a list of clinical cases as well as suggesting the approach of utilizing protein instability.

Data availability statement

The data of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Kim JH, Park E, Hyun HS, Lee BH, Kim GH, Lee JH, Park YS, Kang HG, Ha IS, Cheong HI (2017) Genotype and phenotype analysis in pediatric patients with cystinuria. J Korean Med Sci 32:310–314

Dello Strologo L, Pras E, Pontesilli C, Beccia E, Ricci-Barbini V, de Sanctis L, Ponzone A, Gallucci M, Bisceglia L, Zelante L, Jimenez-Vidal M, Font M, Zorzano A, Rousaud F, Nunes V, Gasparini P, Palacin M, Rizzoni G (2002) Comparison between SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 cystinuria patients and carriers: a need for a new classification. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:2547–2553

Broer S, Wagner CA (2002) Structure-function relationships of heterodimeric amino acid transporters. Cell Biochem Biophys 36:155–168

Wu D, Grund TN, Welsch S, Mills DJ, Michel M, Safarian S, Michel H (2020) Structural basis for amino acid exchange by a human heteromeric amino acid transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:21281–21287

Palacin M, Errasti-Murugarren E, Rosell A (2016) Heteromeric amino acid transporters. In search of the molecular bases of transport cycle mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans 44:745–752

Wagner CA, Lang F, Broer S (2001) Function and structure of heterodimeric amino acid transporters. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281:C1077-1093

Eggermann T, Venghaus A, Zerres K (2012) Cystinuria: an inborn cause of urolithiasis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7:19

Lee SY, Kim JW (2000) Physical analysis of urinary stone using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Ann Lab Med 20:142–149

Font MA, Feliubadalo L, Estivill X, Nunes V, Golomb E, Kreiss Y, Pras E, Bisceglia L, d’Adamo AP, Zelante L, Gasparini P, Bassi MT, George AL Jr, Manzoni M, Riboni M, Ballabio A, Borsani G, Reig N, Fernandez E, Zorzano A, Bertran J, Palacin M, International Cystinuria C (2001) Functional analysis of mutations in SLC7A9, and genotype-phenotype correlation in non-Type I cystinuria. Hum Mol Genet 10:305–316

Ioannidis NM, Rothstein JH, Pejaver V, Middha S, McDonnell SK, Baheti S, Musolf A, Li Q, Holzinger E, Karyadi D, Cannon-Albright LA, Teerlink CC, Stanford JL, Isaacs WB, Xu J, Cooney KA, Lange EM, Schleutker J, Carpten JD, Powell IJ, Cussenot O, Cancel-Tassin G, Giles GG, MacInnis RJ, Maier C, Hsieh CL, Wiklund F, Catalona WJ, Foulkes WD, Mandal D, Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Bustamante CD, Schaid DJ, Hastie T, Ostrander EA, Bailey-Wilson JE, Radivojac P, Thibodeau SN, Whittemore AS, Sieh W (2016) REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am J Hum Genet 99:877–885

Rodrigues CHM, Pires DEV, Ascher DB (2021) DynaMut2: Assessing changes in stability and flexibility upon single and multiple point missense mutations. Protein Sci 30:60–69

Ellard S, Baple EL, Berry I, Forrester N, Turnbull C, Owens MM, Eccles DM, Abbs SJ, Scott R, Deans ZC, Lester T, Jo C, Newman WG, McMullan D (2019) ACGS best practice guidelines for variant classification. https://www.acgs.uk.com/media/11285/uk-practice-guidelines-for-variant-classification-2019-v1-0-3.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee ALQA (2015) Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 17:405–424

SVI Recommendation for Absence/Rarity (PM2)—Version 1.0. Available from: https://clinicalgenome.org/site/assets/files/5182/pm2_-_svi_recommendation_-_approved_sept2020.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023

SVI Recommendation for in trans Criterion (PM3)—Version 1.0. Available from: https://clinicalgenome.org/site/assets/files/3717/svi_proposal_for_pm3_criterion_-_version_1.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2023

Martell HJ, Wong KA, Martin JF, Kassam Z, Thomas K, Wass MN (2017) Associating mutations causing cystinuria with disease severity with the aim of providing precision medicine. BMC Genom 18:550

Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NS, Abeysinghe S, Krawczak M, Cooper DN (2003) Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum Mutat 21:577–581

Chunn LM, Nefcy DC, Scouten RW, Tarpey RP, Chauhan G, Lim MS, Elenitoba-Johnson KSJ, Schwartz SA, Kiel MJ (2020) Mastermind: a comprehensive genomic association search engine for empirical evidence curation and genetic variant interpretation. Front Genet 11:577152

Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alföldi J, Wang Q, Collins RL, Laricchia KM, Ganna A, Birnbaum DP, Gauthier LD, Brand H, Solomonson M, Watts NA, Rhodes D, Singer-Berk M, England EM, Seaby EG, Kosmicki JA, Walters RK, Tashman K, Farjoun Y, Banks E, Poterba T, Wang A, Seed C, Whiffin N, Chong JX, Samocha KE, Pierce-Hoffman E, Zappala Z, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Minikel EV, Weisburd B, Lek M, Ware JS, Vittal C, Armean IM, Bergelson L, Cibulskis K, Connolly KM, Covarrubias M, Donnelly S, Ferriera S, Gabriel S, Gentry J, Gupta N, Jeandet T, Kaplan D, Llanwarne C, Munshi R, Novod S, Petrillo N, Roazen D, Ruano-Rubio V, Saltzman A, Schleicher M, Soto J, Tibbetts K, Tolonen C, Wade G, Talkowski ME, Aguilar Salinas CA, Ahmad T, Albert CM, Ardissino D, Atzmon G, Barnard J, Beaugerie L, Benjamin EJ, Boehnke M, Bonnycastle LL, Bottinger EP, Bowden DW, Bown MJ, Chambers JC, Chan JC, Chasman D, Cho J, Chung MK, Cohen B, Correa A, Dabelea D, Daly MJ, Darbar D, Duggirala R, Dupuis J, Ellinor PT, Elosua R, Erdmann J, Esko T, Färkkilä M, Florez J, Franke A, Getz G, Glaser B, Glatt SJ, Goldstein D, Gonzalez C, Groop L, Haiman C, Hanis C, Harms M, Hiltunen M, Holi MM, Hultman CM, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Kathiresan S, Kim B-J, Kim YJ, Kirov G, Kooner J, Koskinen S, Krumholz HM, Kugathasan S, Kwak SH, Laakso M, Lehtimäki T, Loos RJF, Lubitz SA, Ma RCW, MacArthur DG, Marrugat J, Mattila KM, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Meigs JB, Melander O, Metspalu A, Neale BM, Nilsson PM, O’Donovan MC, Ongur D, Orozco L, Owen MJ, Palmer CNA, Palotie A, Park KS, Pato C, Pulver AE, Rahman N, Remes AM, Rioux JD, Ripatti S, Roden DM, Saleheen D, Salomaa V, Samani NJ, Scharf J, Schunkert H, Shoemaker MB, Sklar P, Soininen H, Sokol H, Spector T, Sullivan PF, Suvisaari J, Tai ES, Teo YY, Tiinamaija T, Tsuang M, Turner D, Tusie-Luna T, Vartiainen E, Vawter MP, Ware JS, Watkins H, Weersma RK, Wessman M, Wilson JG, Xavier RJ, Neale BM, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG, Genome Aggregation Database C (2020) The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 581:434–443

Jung KS, Hong KW, Jo HY, Choi J, Ban HJ, Cho SB, Chung M (2020) KRGDB: the large-scale variant database of 1722 Koreans based on whole genome sequencing. Database (Oxford) 2020:baz146

Jaganathan K, Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou S, McRae JF, Darbandi SF, Knowles D, Li YI, Kosmicki JA, Arbelaez J, Cui W, Schwartz GB, Chow ED, Kanterakis E, Gao H, Kia A, Batzoglou S, Sanders SJ, Farh KK (2019) Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell 176(535–548):e524

Ittisoponpisan S, Islam SA, Khanna T, Alhuzimi E, David A, Sternberg MJE (2019) Can predicted protein 3D structures provide reliable insights into whether missense variants are disease associated? J Mol Biol 431:2197–2212

Yan R, Li Y, Shi Y, Zhou J, Lei J, Huang J, Zhou Q (2020) Cryo-EM structure of the human heteromeric amino acid transporter b(0,+)AT-rBAT. Sci Adv 6:6379

Chillaron J, Font-Llitjos M, Fort J, Zorzano A, Goldfarb DS, Nunes V, Palacin M (2010) Pathophysiology and treatment of cystinuria. Nat Rev Nephrol 6:424–434

Pancotti C, Benevenuta S, Birolo G, Alberini V, Repetto V, Sanavia T, Capriotti E, Fariselli P (2022) Predicting protein stability changes upon single-point mutation: a thorough comparison of the available tools on a new dataset. Brief Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab555

Skopková Z, Hrabincová E, Stástná S, Kozák L, Adam T (2005) Molecular genetic analysis of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes in Czech and Slovak cystinuric patients. Ann Hum Genet 69:501–507

Wong KA, Mein R, Wass M, Flinter F, Pardy C, Bultitude M, Thomas K (2015) The genetic diversity of cystinuria in a UK population of patients. BJU Int 116:109–116

Tostivint I, Royer N, Nicolas M, Bourillon A, Czerkiewicz I, Becker PH, Muller F, Benoist JF (2017) Spectrum of mutations in cystinuria patients presenting with prenatal hyperechoic colon. Clin Genet 92:632–638

Gaildrat P, Lebbah S, Tebani A, Sudrie-Arnaud B, Tostivint I, Bollee G, Tubeuf H, Charles T, Bertholet-Thomas A, Goldenberg A, Barbey F, Martins A, Saugier-Veber P, Frebourg T, Knebelmann B, Bekri S (2017) Clinical and molecular characterization of cystinuria in a French cohort: relevance of assessing large-scale rearrangements and splicing variants. Mol Genet Genomic Med 5:373–389

Egoshi KI, Akakura K, Kodama T, Ito H (2000) Identification of five novel SLC3A1 (rBAT) gene mutations in Japanese cystinuria. Kidney Int 57:25–32

Shigeta Y, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Ahmed N, Sakamoto S, Matsuo H, Kim DK, Fujimura M, Anzai N, Mizoguchi K, Ueda T, Akakura K, Ichikawa T, Ito H, Endou H (2006) A novel missense mutation of SLC7A9 frequent in Japanese cystinuria cases affecting the C-terminus of the transporter. Kidney Int 69:1198–1206

Bisceglia L, Purroy J, Jimenez-Vidal M, d’Adamo AP, Rousaud F, Beccia E, Penza R, Rizzoni G, Gallucci M, Palacin M, Gasparini P, Nunes V, Zelante L (2001) Cystinuria type I: identification of eight new mutations in SLC3A1. Kidney Int 59:1250–1256

Shen L, Cong X, Zhang X, Wang N, Zhou P, Xu Y, Zhu Q, Gu X (2017) Clinical and genetic characterization of Chinese pediatric cystine stone patients. J Pediatr Urol 13:629, e621-629, e625

Sun Y, Man J, Wan Y, Pan G, Du L, Li L, Yang Y, Qiu L, Gao Q, Dan H, Mao L, Cheng Z, Fan C, Yu J, Lin M, Kristiansen K, Shen Y, Wei X (2018) Targeted next-generation sequencing as a comprehensive test for Mendelian diseases: a cohort diagnostic study. Sci Rep 8:11646

Harnevik L, Fjellstedt E, Molbaek A, Denneberg T, Soderkvist P (2003) Mutation analysis of SLC7A9 in cystinuria patients in Sweden. Genet Test 7:13–20

Reig N, Chillaron J, Bartoccioni P, Fernandez E, Bendahan A, Zorzano A, Kanner B, Palacin M, Bertran J (2002) The light subunit of system b(o,+) is fully functional in the absence of the heavy subunit. EMBO J 21:4906–4914

Leclerc D, Boutros M, Suh D, Wu Q, Palacin M, Ellis JR, Goodyer P, Rozen R (2002) SLC7A9 mutations in all three cystinuria subtypes. Kidney Int 62:1550–1559

Bisceglia L, Fischetti L, Bonis PD, Palumbo O, Augello B, Stanziale P, Carella M, Zelante L (2010) Large rearrangements detected by MLPA, point mutations, and survey of the frequency of mutations within the SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 genes in a cohort of 172 cystinuric Italian patients. Mol Genet Metab 99:42–52

Abe Y, Sakamoto S, Morimoto E, Watanabe Y, Nagahara K, Mikawa T, Watanabe S, Itabashi K (2014) Persistent leukocyturia was a clue to diagnosis of cystinuria in a female patient. Glob Pediatr Health 1:2333794X14551275

Rhodes HL, Yarram-Smith L, Rice SJ, Tabaksert A, Edwards N, Hartley A, Woodward MN, Smithson SL, Tomson C, Welsh GI, Williams M, Thwaites DT, Sayer JA, Coward RJ (2015) Clinical and genetic analysis of patients with cystinuria in the United Kingdom. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10:1235–1245

Alghamdi M, Alhasan KA, Taha Elawad A, Salim S, Abdelhakim M, Nashabat M, Raina R, Kari J, Alfadhel M (2020) Diversity of phenotype and genetic etiology of 23 cystinuria saudi patients: a retrospective study. Front Pediatr 8:569389

Tkaczyk M, Gadomska-Prokop K, Zaluska-Lesniewska I, Musial K, Zawadzki J, Jobs K, Porowski T, Rogowska-Kalisz A, Jander A, Kirolos M, Halinski A, Krzemien A, Sobieszczanska-Drozdziel A, Zachwieja K, Beck BB, Sikora P, Zaniew M (2021) Clinical profile of a Polish cohort of children and young adults with cystinuria. Ren Fail 43:62–70

Lotan D, Yoskovitz G, Bisceglia L, Gerad L, Reznik-Wolf H, Pras E (2007) A combined approach to the molecular analysis of cystinuria: from urinalysis to sequencing via genotyping. Isr Med Assoc J 9:513–516

Sakamoto S, Chairoungdua A, Nagamori S, Wiriyasermkul P, Promchan K, Tanaka H, Kimura T, Ueda T, Fujimura M, Shigeta Y, Naya Y, Akakura K, Ito H, Endou H, Ichikawa T, Kanai Y (2009) A novel role of the C-terminus of b 0,+ AT in the ER-Golgi trafficking of the rBAT-b 0,+ AT heterodimeric amino acid transporter. Biochem J 417:441–448

Tohge R, Sakamoto S, Takahashi M (2016) A case of cystinuria presenting with cerebellar ataxia and dementia. Pract Neurol 16:296–299

Okada T, Taguchi K, Kato T, Sakamoto S, Ichikawa T, Yasui T (2021) Efficacy of transurethral cystolithotripsy assisted by percutaneous evacuation and the benefit of genetic analysis in a pediatric cystinuria patient with a large bladder stone. Urol Case Rep 34:101473

Ikeyama S, Kanda S, Sakamoto S, Sakoda A, Miura K, Yoneda R, Nogi A, Ariji S, Shimoda M, Ono M, Kanda S, Yokoyama S, Takahashi K, Yokoyama Y, Hattori M (2022) A case of early onset cystinuria in a 4-month-old girl. CEN Case Rep 11:216–219

Zhan R, Ge Y, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Wang W (2022) Genetic and clinical analysis of Chinese pediatric patients with cystinuria. Urolithiasis 51:20

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: BL, HDP. Data curation: BL, SYL, HDP. Resources: SYL, DHH, HDP. Project administration: DHH, HDP. Writing: original draft: BL. Writing: review and editing: BL, HDP.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, B., Lee, SY., Han, D.H. et al. Interpretation of SLC3A1 and SLC7A9 variants in cystinuria patients: The significance of the PM3 criterion and protein stability. Urolithiasis 51, 94 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-023-01466-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-023-01466-y