Abstract

Background

The LIMB-Q is a newly developed patient-reported outcome measure (PROM), applicable for lower extremity trauma patients requiring fracture treatment, soft tissue debridement, reconstruction, and/or amputation. The aim of this study was to translate and linguistically validate the LIMB-Q from English to Danish.

Method

The translation and linguistic validation were performed by combining guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR). This approach involved 2 forward translations, a backward translation, an expert panel meeting, and 2 rounds of cognitive patient interviews. The main goal of these steps was to achieve a conceptual translation with simple and clear items. Feedback from the Danish translation was used in combination with psychometric analyses for item reduction of the final international version of LIMB-Q.

Results

In the forward translation, 6 items were found difficult to translate into Danish. The two translations were harmonized to form the backward translation. From the backward translation, 1 item was identified with a conceptually different meaning and was re-translated. The revised version was presented at the expert panel meeting leading to revision of 10 items. The cognitive patient interviews led to revision of 11 items. The translation process led to a linguistically validated and conceptually equivalent Danish version of the LIMB-Q.

Conclusion

The final Danish LIMB-Q version consisting of 16 scales is conceptually equivalent to the original and ready for field-testing in Denmark.

Level of evidence: Not gradable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lower extremity injuries from the acetabulum to the toes are common; however, they vary in complexity and their impact on patients [1]. Having a severe lower extremity (LE) injury can be devastating and lead to a significant reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQL) [2, 3]. Treatments vary, ranging from fracture reduction and open fixation with or without debridement to multiple surgeries in an attempt to salvage severely mangled extremities, and in some cases primary or secondary amputation. Several systematic reviews [4,5,6,7,8] attempted to offer recommendations regarding the optimal treatment strategy for severe LE injuries but they failed to establish a definitive consensus. A common trend for these studies, examining the patient perspective, was the use of patient-reported outcome measure (PROMs) that were either generic or not developed for severe LE trauma necessitating limb reconstruction and/or amputation. PROMs assess outcomes that are subjective and can only be reported by patients, such as pain or HRQL. Generic PROMs can be used for comparison between lower extremity trauma patients and the general population or other conditions. However, they lack the specificity required to accurately assess outcomes that are important to these patients. Consequently, they are unsuitable to accurately assess outcomes for these patients and to draw valid conclusions about their treatment. LE injuries and the resulting treatment have a widespread impact on patients’ lives [3, 9]. Therefore, capturing what is important to these patients with PROMs is of paramount importance. However, to be able to draw evidence-based conclusions, a rigorously developed and condition-specific PROM must be used. Mundy et al. found [10] that there is a lack of PROMs specifically developed for lower extremity trauma patients undergoing reconstruction and/or amputation. This has prompted the development of the LIMB-Q questionnaire. The LIMB-Q is a condition-specific PROM applicable to adults who have experienced an LE trauma below the mid-femur, and have undergone fracture surgery, soft tissue debridement, reconstruction, and/or amputation as part of their treatment [9,10,11,12]. LIMB-Q was developed following international guidelines [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] in an international, multi-disciplinary collaboration of orthopedic and plastic surgeons working closely together with PROM development research scientists [11]. In the first phase, a conceptual framework and preliminary set of 20 scales containing 382 items were developed from 33 qualitative interviews with LE trauma patients [9,10,11]. In the second phase, further refinements of the scales and content validity were established through 12 cognitive patient interviews and input from 43 experts [12]. The third phase consisted of a field-test and was conducted in the USA and the Netherlands simultaneously with the present study [21]. To the best of our knowledge, LIMB-Q is the only rigorously developed PROM specifically for LE trauma patients, relevant to patients following fracture surgery, soft tissue debridement, and reconstruction as well as amputation [10]. The aim of this study was to perform an advanced Danish translation and cultural adaptation of the 20 preliminary LIMB-Q scales, and provide feedback for the LIMB-Q developers to be used together with field-test data to achieve a final Danish and International version of the LIMB-Q.

Materials and methods

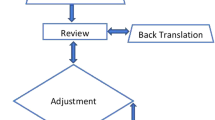

Prior to conducting this study, approval was obtained from the Danish Data Protection agency, and approval to translate the LIMB-Q was obtained from LIMB-Q developers. The translation process followed the method described by Poulsen et al. [22] combining ISPOR [19] and WHO guidelines of translation and cultural adaptation (Fig. 1). An interview guide for patients’ interviews and excel worksheet from August 2021 were provided for data collection by the LIMB-Q developers and were used throughout the process. The interview guide focused on identifying instructions, items, or response options that were difficult to understand. To get further insights, all participants in this study were asked if the content of the scales was relevant and comprehensive (i.e., no key aspect was missing) [23]. These results were used to inform item selection in the psychometric analysis to finalize content included in the LIMB-Q making this an advanced translation [21].

Forward translation

Forward translations of the field-test version of the LIMB-Q scales were performed by both a professional translator and a clinician, creating two independent translations. Both individuals were native Danish speakers and fluent in English. Discrepancies between the two translations were discussed and resolved in a reconciliation meeting. If the translators could not reach an agreement, discrepancies were discussed with the LIMB-Q developers. The forward translation process led to the Danish LIMB-Q version 1.0.

Backward translation

A professional native-English translator, who was fluent in Danish, performed the backward translation of the Danish LIMB-Q version 1.0 into English. The backward translation was sent to the LIMB-Q developers and compared with the original English version. All discrepancies were noted and discussed with LIMB-Q developers (AFK, LRM). Items with a different conceptual meaning from the original English version were re-translated and discussed. This step continued until a satisfactory result was achieved, leading to the Danish LIMB-Q version 2.0.

Expert panel meeting

An expert panel meeting was conducted. The aim was to identify and resolve any Danish content that could be improved upon (e.g., made simpler or clearer), and to confirm all clinically relevant issues that might be unique to a Danish population were captured. The panel consisted of two forward translators, one backward translator, two plastic surgeons, two orthopedic surgeons, one nurse with expertise in lower limb injuries, one physiotherapist, two patients, and a notetaker. Prior to the meeting, the Danish version 2.0, translation guidelines, and instructions were sent for the participants to review. Feedback was discussed with the LIMB-Q developers and integrated into the Danish version 3.0.

Cognitive debriefing interviews

Two rounds of cognitive debriefing interviews with patients were performed to determine if the instructions, items, and response options were easy to understand, relevant, and comprehensive. All interviews were performed by the first author. Prior to these interviews, participants were provided with instructions, asked to read the PROM, and note any difficulties. Interviews were performed online, by phone, or in person. In the first round, 10 patients were included and evaluated the Danish version 3.0. Any difficulties experienced by the patients or comments about relevance and comprehensiveness were noted in the excel worksheet. Findings were discussed with the LIMB-Q developers. After round 1, the original LIMB-Q field-test study ended and psychometric analysis was conducted leading to item reduction. Findings from the Danish translation were used to inform item selection of the field-tested LIMB-Q version [21]. The Danish version 3.0 was shortened to reflect the finalized version of the LIMB-Q, leading to the Danish version 3.1. This version was evaluated in round 2 by two patients to ensure that final changes based on the field-test study and the first round of cognitive interviews were acceptable, leading to the Danish version 4.0.

Proofreading and finalization

The first author and a research assistant independently proofread the Danish LIMB-Q version for spelling and grammatical errors, leading to the final Danish LIMB-Q.

Results

Forward translation

Discrepancies between the two forward translations were consistent with different views on the language and different knowledge about the patient group and medical terms. The primary discrepancy was the translation of “lower limb.” The clinician translated “lower limb” to “lower extremity,” and the professional translator translated the word to “lower leg.” However, lower leg does not include the entire lower extremity, as intended for this term. The reason for the discrepancy was the term “lower limb” does not exist in the Danish language in the same way it does in English. The solution, after discussion with the LIMB-Q developers, was to add examples: “Leg (e.g., foot, ankle, lower leg, knee, thigh).” In total, 16 items were found difficult to translate into Danish, three required discussions with the LIMB-Q developers, and ultimately nine items that were problematic in the translation were dropped based on the results of the international field-test.

Backward translations

The developers compared the original English LIMB-Q version with the backward translated Danish LIMB-Q version 1.0. They identified that an instruction in the financial scale and one item in the sexual scale had a different meaning. No alterations were made to the instruction, which was eventually removed after the field-test. The item in the sexual scale was rephrased. The original item was “Find sex physically easy with your lower limb?” and the backtranslation was “Are not physically hampered by your leg during sex?” The item was rephrased into “finds sex physically easy despite your leg” and discussed during the expert panel meeting.

Expert panel meeting

The expert panel meeting was conducted virtually and lasted 2 h. It included a presentation of the original English version, the backtranslation, and the Danish version. All items and all scales were evaluated. Items that were found troublesome in previous translation steps were discussed in depth. The experts identified eight items for discussion with the LIMB-Q developers, and 15 items to be further explored in the cognitive interviews. As a representative example, the term “energy” in the item “How much energy it takes to walk using the prosthesis” was found unclear. The experts suggested to change “energy” to “strenuous” or “exhausting.” In the cognitive interview, the patients were presented with this change and asked which wording they preferred. In total, the expert panel meeting resulted in the revision of 30 items. Of these 30 items, 20 were deleted after the field-test.

Cognitive debriefing interviews

A total of 12 patients participated in the cognitive interviews. Purposeful sampling was used to recruit for a variety in injury severity and treatment needs. Participant characteristics are described in Table 1. In the first round, all 20 LIMB-Q scales were examined. All instances of participants stating that a scale, instruction, response options, or any items were not easy to understand, not relevant, or missing concepts were noted in an Excel worksheet. After the LIMB-Q was reviewed, participants provided feedback on the items that were identified as problematic by the expert panel, which led to revision of two items. At the end of this round, a total of 20 items were deemed problematic items and shared with the LIMB-Q developers to inform item-reduction as part of the psychometric analysis. Of these, eight items were excluded from the final version. After psychometric analysis and feedback from translations into German, Dutch, and Danish, the LIMB-Q was reduced to 16 independently functioning scales, with a total of 164 items, measuring the 4 domains: Limb, HRQL, Experience of care, and Treatment. The item-reduced version of the LIMB-Q included 12 items that were deemed potentially problematic in the translation. For example, one item asked, “The color of the amputated part of your limb?.” Patients found it strange to ask about the color of something that was removed, and it was rephrased into “The color of your residual limb.” Of the 12 items, nine were revised based on patient feedback to improve comprehensibility. In the second round, the Danish LIMB-Q version 3.1, which included 16 scales (164 items), was examined by the participants. Two items were revised, one to include the clarification “(e.g., not as flat as you would like)?” and the other item was rephrased. These changes lead to the Danish version 4.0. Examples of discrepancies and changes made in the translation process are available in Table 2.

Proofreading

Minor grammatical mistakes, spelling, layout, and punctation changes were made. The final LIMB-Q measures four domains: Limb, HRQL, Experience of care, and satisfaction with Treatment. Each domain ranges between three to six scales, and each scale can be used separately. The conceptual framework is available in Fig. 2.

Discussion

In this study, we translated from English to Danish the field-test version of the LIMB-Q, following a rigorous scientific process combining ISPOR [24] and WHO guidelines as described by Poulsen et al. [22]. Following the translation process, we achieved a culturally adapted and conceptually equivalent Danish LIMB-Q version. Together with psychometric analysis, the LIMB-Q team used feedback from the various translation teams (Danish, Dutch, German) in the final item selection, promoting a greater international relevance [21]. This combination of the data with the international field test led to the final LIMB-Q.

The final version of LIMB-Q consists of 16 scales with 164 items, with response options ranging from 3 to 4. The psychometric analysis, described elsewhere [21], shows that the LIMB-Q evidenced reliability and validity for LE trauma patients, including those undergoing fracture fixation, soft tissue reconstruction, or amputation. Using PROMs is especially important in LE trauma patients given how impactful these injuries are on patients’ lives. To ensure the LIMB-Q content is relevant to Danish people with LE trauma, we recruited a diverse sample of 14 patients who took part in the expert panel and cognitive debriefing interviews. This exceeds the ISPOR recommendation of 5 to 8 respondents [24]. A larger sample was selected to help ensure we adequately captured the diversity of the lower extremity patient experience, and that all linguistic changes were easily comprehensible, acceptable, and relevant for lower extremity trauma patients. We included seven people with assistive devices to maximize the likelihood that the content was relevant to this patient group [25].

Despite LIMB-Q being developed in different countries, cultures, and health systems, the Danish patients found that the content of LIMB-Q was relevant to them. However, in some cases, the experts and patients disagreed about which items or scales were relevant. For example, most of the experts thought the financial scale was irrelevant, as everybody has access to healthcare in Denmark. In cognitive interviews, 9 out of 12 participants disagreed, as they experienced a financial impact from lower income due to sick leave, early retirement, or expenses for prostheses and assistive devices. This clearly illustrates the importance of actively involving patients to ensure the relevance and comprehensiveness of such measures, and that PROMs cannot be effectively undertaken by clinicians or researchers alone. As expected, the heterogeneity of the injuries and varying stages of recovery resulted in patients exhibiting diverse levels of physical function. After item reduction, 22 items were removed from the function scale. The content of the remaining 15 items and notes from the cognitive interviews was discussed with the LIMB-Q developers. It became clear that the function scale was only applicable for patients who were capable of walking to some extend (ambulating). This criterion was therefore included in the instructions.

There were certain limitations to our study. Firstly, the cognitive debriefing interviews and expert panel meeting were not recorded. Consequently, we had to rely on the notes taken by the interviewer and the notetaker for reference. Nonetheless, all items that were perceived as unclear, irrelevant, or missing in the scales during the interviews were noted in the excel worksheet for further consideration. Furthermore, the main goal of this study was to perform a linguistic validation and cultural adaption of the LIMB-Q rather than focusing on a comprehensive content validity assessment. The advanced Danish translation of the LIMB-Q was initiated while the international field-test was already in progress. As a result, the Danish feedback could only be used to guide item reduction and refinement, rather than making significant modifications, such as adding new content to the field-test version [26]. The translation process is carried out iteratively, acknowledging that the final decisions regarding wording, examples, and phrasing involve a certain degree of subjectivity. This is done to ensure consistency across translation and to address any linguistic nuances or cultural variances that may arise. However, by including a large number of experts and patients, only relevant adjustments were made. We did not include a prosthetist in the expert panel; however, both a physiotherapist and a patient with an osseointegrated prosthesis were included. Finally, the versatility of the LIMB-Q is both an advantage and a limitation. It covers a wide range of conditions, including life-changing amputation, failed treatments lasting for years, orthoplastic approaches, and minor injuries like ankle fractures. However, not all items may be relevant to every patient group, which can be considered a limitation. Additionally, it should be noted that the LIMB-Q is not suitable for pediatric patients. Instead, a separate questionnaire called the LIMB-Q Kids is developed for pediatric patients with limb deformities [27,28,29,30].

There are several strengths associated with the translation process. The utilization of both ISPOR and WHO guidelines secured a thorough translation considering that there are variations and differences between the guidelines provided by these two organizations [22]. The most significant difference is the recommendation of an expert panel meeting by the WHO and the more detailed description of the translation process by ISPOR. The methodology has been found valuable in several studies [22, 28, 31]. By translating the LIMB-Q before the item-reduction phase, we provided feedback about problematic items to the developers. This feedback was used alongside other psychometric evidence to make final decisions about which items and scales to retain in the item-reduction phase. This ensured that only the best items were kept in the final LIMB-Q. By including patients in the expert panel, the patient’s voice was well integrated, and clinician-driven changes that were not reflective of patients were stopped prior to cognitive debriefing interviews. This prevented unnecessary re-translations, but also ensured patient understanding of those items that needed to be rephrased, saving time and unnecessary discussions.

In conclusion, a conceptually equivalent and culturally adapted Danish version of the LIMB-Q is now available for Danish patients with LE injuries below the mid-femur requiring fracture surgery, soft tissue reconstruction, and/or amputation. The Danish LIMB-Q is available at https://qportfolio.org/ and can be used to measure a wide range of outcomes important for these patients. The next step will include a psychometric validation, to ensure that the PROM is reliable and valid in the Danish population.

References

Lambers K, Ootes D, Ring D (2012) Incidence of patients with lower extremity injuries presenting to US emergency departments by anatomic region, disease category, and age. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(1):284–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1982-z

Costa ML, Achten J, Bruce J, Tutton E, Petrou S, Lamb SE, Parsons NR, Collaboration UW (2018) Effect of negative pressure wound therapy vs standard wound management on 12-month disability among adults with severe open fracture of the lower limb: the WOLLF randomized clinical trial. JAMA 319(22):2280–2288. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.6452

Leggett H, Scantlebury A, Byrne A, Harden M, Hewitt C, O’Carroll G, Sharma H, McDaid C, Collaborators PS (2021) Exploring what is important to patients with regards to quality of life after experiencing a lower limb reconstructive procedure: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 19(1):158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01795-9

Schirò GR, Sessa S, Piccioli A, Maccauro G (2015) Primary amputation vs limb salvage in mangled extremity: a systematic review of the current scoring system. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16:372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0832-7

Ng HJH, Ang EJG, Premchand AXR, Rajaratnam V (2023) Limb salvage versus primary amputation in Gustilo-Anderson IIIB and IIIC tibial fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-023-04804-2

Akula M, Gella S, Shaw CJ, McShane P, Mohsen AM (2011) A meta-analysis of amputation versus limb salvage in mangled lower limb injuries–the patient perspective. Injury 42(11):1194–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2010.05.003

Saddawi-Konefka D, Kim HM, Chung KC (2008) A systematic review of outcomes and complications of reconstruction and amputation for type IIIB and IIIC fractures of the tibia. Plast Reconstr Surg 122(6):1796–1805. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818d69c3

Busse JW, Jacobs CL, Swiontkowski MF, Bosse MJ, Bhandari M, Working E-B, G. (2007) Complex limb salvage or early amputation for severe lower-limb injury: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Orthop Trauma 21(1):70–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802cbc43

Mundy LR, Klassen A, Grier AJ, Gibbons C, Lane W, Carty MJ, Pusic AL, Hollenbeck ST, Gage MJ (2020) Identifying factors most important to lower extremity trauma patients: key concepts from the development of a patient-reported outcome instrument for lower extremity trauma, the LIMB-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 145(5):1292–1301. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000006760

Mundy LR, Grier AJ, Weissler EH, Carty MJ, Pusic AL, Hollenbeck ST, Gage MJ (2019) Patient-reported outcome instruments in lower extremity trauma: a systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7(5):e2218. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002218

Mundy LR, Klassen A, Grier J, Carty MJ, Pusic AL, Hollenbeck ST, Gage MJ (2019) Development of a patient-reported outcome instrument for patients with severe lower extremity trauma (LIMB-Q): protocol for a multiphase mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc 8(10):e14397. https://doi.org/10.2196/14397

Mundy LR, Klassen A, Sergesketter AR, Grier AJ, Carty MJ, Hollenbeck ST, Pusic AL, Gage MJ (2020) Content validity of the LIMB-Q: a patient-reported outcome instrument for lower extremity trauma patients. J Reconstr Microsurg. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713669

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2010) The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 19(4):539–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC (2010) The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 63(7):737–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

Rasch G (1960) Studies in mathematical psychology: 1. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Copenhagen, Denmark

Health, U. S. D. o., Human Services, F. D. A. C. f. D. E., Research, Health, U. S. D. o., Human Services, F. D. A. C. f. B. E., Research, Health, U. S. D. o., Human Services, F. D. A. C. f. D., & Radiological, H. (2006). Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-4-79

Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, Lohr KN, Patrick DL, Perrin E, Stein RE (2002) Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 11(3):193–205

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L, Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L (2011) Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1–eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 14(8):967–977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L (2011) Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2–assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 14(8):978–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013

Hobart J, Cano S (2009) Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Assess 13 (12), iii, ix-x, 1–177. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13120

Mundy LR, Klassen A, Pusic A, DeJong T (2023) The LIMB-Q: reliability and validity of a novel patient-reported outcome measure for lower extremity trauma patients. PRS

Poulsen L, Rose M, Klassen A, Roessler KK, Sorensen JA (2017) Danish translation and linguistic validation of the BODY-Q: a description of the process. Eur J Plast Surg 40(1):29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-016-1247-x

Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, Westerman MJ, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW, Mokkink LB (2018) COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res 27(5):1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0

Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P, Translation ITFf and Cultural A (2005) Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 8(2):94–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x

Miller R, Ambler GK, Ramirez J, Rees J, Hinchliffe R, Twine C, Rudd S, Blazeby J, Avery K (2021) Patient reported outcome measures for major lower limb amputation caused by peripheral artery disease or diabetes: a systematic review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 61(3):491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2020.11.043

Dorer B (2023) Advance translation—the remedy to improve translatability of source questionnaires? Results of a think-aloud study. Field Methods 35(1):33–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x211072343

Chhina H, Klassen A, Bade D, Kopec J, Cooper A (2022) Establishing content validity of LIMB-Q Kids: a new patient-reported outcome measure for lower limb deformities. Qual Life Res 31(9):2805–2818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03140-z

Vogt B, Fresen J, Gosheger G, Chhina H, Brune CS, Toporowski G, Frommer A, Laufer A, Cooper A, Roedl R, Rölfing JD (2022) LIMB-Q Kids-German translation and cultural adaptation. Children (Basel), 9 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091405

Chhina H, Klassen A, Kopec JA, Oliffe J, Cooper A (2019) International multiphase mixed methods study protocol to develop a patient-reported outcome instrument for children and adolescents with lower limb deformities. BMJ Open 9(5):e027079. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027079

Jønsson CE, Poulsen L, Rölfing JD, Chhina H, Cooper A, Sørensen JA (2023) Danish linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of the LIMB-Q Kids. Children 10(7):1107. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/10/7/1107

van Alphen TC, Poulsen L, van Haren ELWG, Jacobsen AL, Tsangaris E, Sørensen JA, Hoogbergen MM, van der Hulst RRJW, Pusic AL, Klassen AF (2019) Danish and Dutch linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of the WOUND-Q, a PROM for chronic wounds [journal article]. Eur J Plast Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-019-01529-7

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the patients’ willingness and interest to participate in this study. Moreover, we would like to express our gratitude to our colleagues, who either participated in the consensus meetings or helped to recruit patients.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Odense University Hospital This work was supported by grants from “Odense University Hospital PhD fund” (grant number A4774) Odense University Hospital and the “Region of Southern Denmark PhD fund” (grant number 21/58368).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection agency (Journal number 20/35066), and approval to translate the LIMB-Q was obtained from LIMB-Q developers. No ethical approval was necessary from the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee of Southern Denmark as this study was a questionnaire and interview survey.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent to publish

No data that were person identifiable was published. All participants were informed about publication and did not object.

Competing interests

Drs. Mundy, Pusic, and Klassen are co-developers of the LIMB-Q and could potentially receive a share of any license revenue on the inventor sharing policies from the institutions that own the LIMB-Q. None of the authors has a financial or non-financial interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simonsen, N.V., Rölfing, J.D., Mundy, L.R. et al. Danish translation and linguistic validation of the LIMB-Q, a PROM for traumatic lower limb injuries and amputations. Eur J Plast Surg 46, 1255–1264 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-023-02107-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-023-02107-8