Abstract

The paper presents verification and validation of an advanced numerical model of heat and moisture transfer in the multi-layer protective clothing and in components of the experimental stand subjected to either high surroundings temperature or high radiative heat flux emitted by hot objects. The developed model included conductive-radiative heat transfer in the hygroscopic porous fabrics and air gaps as well as conductive heat transfer in components of the stand. Additionally, water vapour diffusion in the pores and air spaces as well as phase transition of the bound water in the fabric fibres (sorption and desorption) were accounted for. All optical phenomena at internal or external walls were modelled and the thermal radiation was treated in the rigorous way, i.e., semi-transparent absorbing, emitting and scattering fabrics with the non-grey properties were assumed. The air was treated as transparent. Complex energy and mass balances as well as optical conditions at internal or external interfaces were formulated in order to find values of temperatures, vapour densities and radiation intensities at these interfaces. The obtained highly non-linear coupled system of discrete equations was solved by the Finite Volume based in-house iterative algorithm. The developed model passed discretisation convergence tests and was successfully verified against the results obtained applying commercial software for simplified cases. Then validation was carried out using experimental measurements collected during exposure of the protective clothing to high radiative heat flux emitted by the IR lamp. Satisfactory agreement of simulated and measured temporal variation of temperature at external and internal surfaces of the multi-layer clothing was attained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Firefighters, soldiers, motor sportsmen and workers during their duties may be exposed to either high ambient temperature or high heat fluxes coming from hot external objects, e.g., flame or hot bodies. They may also came into direct contact with hot surfaces. Therefore, they wear special personal protective garments, which play dual role. Firstly, the protective garments maintain comfortable conditions during regular activities of people. Secondly, they protect the workers from getting severe burn injuries or minimize harmful thermal effects during the emergency situations. The regular activates are more likely and usually occur continuously. The later events are less likely and occur for a very short time, usually until the person escape from the scene.

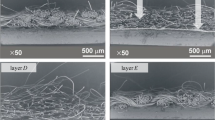

Typical protective clothing consists of several (three or four) textile layers, e.g., the outer shell, moisture barrier, thermal insulation and lining. Each of these fabric has different thermophysical and optical properties and performs different role. The outer shell, which is the most external layer, is responsible for protection against short thermal and mechanical hazards. The penetration of either cold or hot water or other liquids is prevented by the moisture barrier. The thermal insulation secures from the increase of temperature at the inner side of the clothing during short- or long-term heat exposures. The comfort of exploitation of the garments is ensured by the lining. Moreover, the fabrics may be separated by thin air gaps. The widest air gap is usually present between the inner clothing surface and the skin.

The protective clothing is considered as a porous, multi-component and multi-phase structure in which all basic heat transfer modes, i.e., conduction, convection and thermal radiation are present. In the garments the heat is conducted through the fibres in the fabric and motionless air in the pores and gaps. The forced convection in the garments is usually associated with a movement of the person and related variation of the size of the air space between the skin and inner clothing surface. Sometimes it can be induced by either direct contact of the clothing with a flame or a blast of the external air. The fabrics are also semi-transparent and non-grey media which interact with thermal radiation. The radiative heat flux which is emitted by the external radiation heat source, e.g., flame or hot body is attenuated by absorption and scattering in the volume of the fabrics before reaching the skin. In the protective clothing all these heat transfer modes mentioned above are strongly coupled and non-linear as well as dependent on both thermophysical and optical properties of fabrics as well as the structure of textile layers. Moreover, during wearing of the protective clothing the moisture transport should be also considered. The water content in the clothing system may come from the surroundings or from the human body due to sweating and epidermal water loss. Therefore, the heat transfer phenomena in the protective garments are accompanied by the diffusion and convection of water vapour in the textile layers and air gaps as well as by sorption and desorption of a moisture in the fabric fibres and phase transition of water at the skin surface. The moisture in a complex way affects energy transfer as well as thermophysical and optical properties of the fabrics, e.g., presence of the moisture increases the effective thermal conductivity and specific heat of fabrics. What is more, in the emergency situation thermochemical reactions in the fibres and changes in the fabric structure as well as in their effective optical and thermophysical properties may also appear as a results of substantial increase of the clothing temperature. The above description shows that the heat and mass transport phenomena in the multilayer protective clothing are very complex and their modelling is challenging.

The problem of mathematical and numerical modelling of transport phenomena in the protective garments was undertaken many times [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, the complex nature of heat and mass transfer phenomena in the multilayer protective clothing resulted in many simplifications which were introduced into proposed heat and mass transfer models. Therefore, development of thermal models of the protective garments should be accompanied by carefully credibility analysis. In other words the obtained results should be verified against benchmark solutions and validated against experimental data. The first significant one-dimensional thermal model of a single flame-resistant fabric layer for heating period under high heat flux conditions was developed and validated by Torvi and Dale [1]. The model was farther extended to account for multi-layer nature of the protective clothing and presence of a cooling period after thermal exposition by Torvi and Threlfall [2]. Both models dealt with conductive-radiative heat transfer in the fabric and across the air space between the fabric and test sensor which measured temperature on the skin side. Heat conduction in the sensor was also included. The absorption of thermal radiation in the fabric was modelled applying the simplified Beer’s law based model. Moreover, thermochemical reactions in the textile layers, which affected fabric thermal properties, were accounted for. The Finite Element Method was used to solve the resulting governing equations. The temperature variation predicted by applying the developed numerical models [1, 2] and Stroll second-degree burn criterion [1] were compared with those determined experimentally. Very good agreement of the obtained results was found. In the next paper Mell and Lawson [3] developed conductive-radiative heat transfer model in a clothing assembly composed of several fabrics separated by the thin air gaps. They accounted for radiative heat transfer in this multilayer clothing in a simplified way using two-step approach. In the first step the textile layers were assumed semi-transparent and the Beer’s law based model was applied with averaged optical properties of fabrics obtained by integrating their wavelength dependent values. Then in the second step the air gaps were assumed transparent and limited by infinitely thin textile layers (planes) which absorbed, transmitted and reflected thermal radiation. The credibility analysis of the model was based on the verification, using solution of the simplified analytical problem, and on the validation using measurements carried out for the three-layer protective turnout coat. Accuracy of the model was found very well. Subsequently, Song et al. [4] developed a numerical thermal model to predict the skin burn injury resulting from heat transfer through a single-layer protective garment worn by an instrumented manikin submitted to laboratory-controlled flash fire exposures. The model dealt with conductive and radiative heat transfer in a similar manner to models described in [1,2,3]. Moreover, the model accounted for characteristics of the experimentally simulated flash fire generated in the test chamber, the heat-induced variation in the fabric thermophysical properties and the air gap between the garment and the manikin. The model was validated using an instrumented manikin fire test system. The first one-dimensional model, which accounted for conjugated conductive and radiative heat transfer accompanied by the moisture transport in the multi-layer firefighter protective garment during the flash fire exposure and subsequent cooling process, was developed by Chitrphiromsri and Kuznetsov [5] and then validated by Song et al. [6]. They treated the fabrics as a multi-component hydroscopic porous structure which consisted of the solid fibres, bound water and the mixture of dry air and water vapour. Radiative heat transfer was modelled in a simplified way with Beer’s law based model similarly as in the previous papers [1,2,3]. The validation of the developed model was based on the experimental results obtained for different fabric systems (i.e., from one- through two- to multi-layer ones) and for different system configurations (i.e., without and with an air gap between the garment and the sensor). Good matching between model predictions and experimental measurements was found. Subsequently, Ghazy and Bergstrom [7, 8] developed a thermal model of the protective gear composed of a single-layer fire resistant fabric [7] and of three fabric layers separated by two air gaps [8]. They dealt in a more sophisticated way with the air gap between the fabric and the sensor (skin simulant) than in the previous models [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Namely, the simplified Beer’s law based model was used to account for absorption of the incident thermal radiation in the semi-transparent textile layers while the radiative transfer equation was solved in the air gaps with the fixed value of absorption coefficient. The model for a single fabric layer was validated by applying data from the thermal protective performance tests. Numerically calculated variation of the temperature of the sensor (skin simulant) during both the exposure and cool down periods closely followed the experimental observations. The next model of a coupled heat and moisture transfer during combined drying and pyrolysis process of the wet fabrics was developed and validated by Zhu and Li [9]. The drying process was described by the one-step chemical reaction. Moreover, the model included heat-induced changes in the fabric thermophysical properties following from the pyrolysis. The model was validated using experimental data from modified radiant protective performance tests of a single cotton fabric. The comparison showed that predictions of mass loss rates, temperature profiles in the charring fabric and skin simulant as well as the required time to the second degree skin burn were in reasonably good agreement with the experimental results. Another thermal model dealing with the flame-resistant fabric which shielded the cylinder simulating human limb and exposed to convective and radiative heat fluxes from a fire was proposed by Zhu et al. [10]. The model was based on the model developed in [1] and accounted for heat induced changes in the fabric and dry air thermophysical properties. The results of simulations were validated by experimental tests. The calculated temperature variations at the front and back side of fabric and at the skin simulant were compared with experimentally measured distributions for the single textile layer. Satisfactory accuracy of the predictions was found. An integrated numerical simulator, which combined one- and three-dimensional modelling and enabled both the estimation of burn injuries originating from fire disasters as well as the assessment of the quality of the protective clothing, was reported by Jiang et al. [11]. The one-dimensional in-house model accounted for radiative-conductive heat transfer in the clothing and human skin simulant, while three-dimensional model, which was implemented in the general-purpose computational fluid dynamics software, allowed to determine fluid flow and heat transfer in an in situ fire event. Both models were coupled in a double-way. The predicted temperature distributions in the clothing, heat fluxes on the skin simulant surface and the burn degrees agreed reasonably well with the experimental data conducted by applying the full-scale benchmark aperture. Recently, Fu et al. [12] modelled one-dimensional heat and moisture transport in the multi-layer protective garment with the air gaps exposed to low levels of thermal radiation emitted in the surroundings. The proposed model accounted for absorption of thermal radiation by the water vapour which was presented in the pores of the fabrics and in the air gaps. Numerical results compared well with the experimental ones. In the latest paper Udayraj et al. [13] proposed a realistic and detailed three-dimensional transient numerical model of fluid motion and heat transfer through the air gap between the fabric and test sensor. The model accounted for coupled conduction, convection and radiation in the system. The effect of the horizontal and vertical air gap orientations as well as the dynamic variation of air gap size on the sensor temperature and heat flux, thermal protection ability and fluid flow patterns in the gap were analysed. The heat transfer in the clothing was not accounted for. Prediction of the model were compared with the available experimental results for various air gaps and the agreement with the obtained results was found satisfactory. The model was then coupled with the Pennes bio-heat transfer model in the human skin and influence of the air gap width and orientations as well as heterogeneous air gap on the skin burn were investigated [14].

Recently, a new one-dimensional model of heat and moisture transfer in the multi-layer protective garments exposed to high radiative heat flux emitted by the external heat source was proposed by Łapka et al. [15,16,17]. The developed model in a detailed and rigorous way accounted for thermal radiation which was emitted by the external heat source, penetrated the fabrics and air gaps and was absorbed by the human skin or skin simulating material. The semi-transparent porous and hygroscopic textile layers were assumed non-grey and absorbing, emitting and scattering thermal radiation. Additionally, the model accounted for optical phenomena, i.e., either reflection and transmission or absorption, emission, reflection and transmission of thermal radiation at interfaces separating different layers of the clothing. Moreover, complex energy and moisture balances as well as optical conditions at the internal or external interfaces were formulated in order to account for exact values of temperatures, vapour densities and radiation intensities at these interfaces. The proposed model was then applied to study influence of different heat transfer modes on temperature distribution in the protective clothing and skin [18], compare different bio-heat transfer models used in the assessment of burns injuries [19] and evaluate the human skin surface temperature in the protective clothing-skin system based on the protective clothing-skin imitating material results [20]. Although, the model predictions were reasonable, its accuracy has been not validated. Only simplified verification was carried out [21]. Therefore, a wide verification and validation analyses of the developed model are carried out in this paper. The three step credibility analysis of the model is proposed. In the first step the influence of spatial, time, angular and wavelength discretization levels on the solution convergence were investigated. Then in the second step the model predictions for several simplified cases were compared with the results obtained by applying the commercial software. Finally, in the last step the results obtained using the developed model were compared with the experimental data obtained during the exposure of the multi-layer protective clothing to high radiative heat flux emitted by the IR lamp.

2 Mathematical formulation

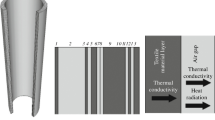

The system under consideration was composed of three fabric layers: the outer shell, moist barrier and thermal insulation separated by two narrow air gaps, the wide air gap and the plate stabilizing temperature as presented in Fig. 1. The numbers of fabric layers and its combinations with the air gaps are not limited and may be easily modified (see section 5.2 where the system with four layers and three air gaps was considered). The external heat source was located on the left hand side, while the right boundary was convectively cooled by flowing water from the ultra-thermostat. The model assumed one-dimensional heat and moisture transfer due to the small thickness of the considered system in comparison to its lateral dimensions along the protective clothing and assumed no variation of the external thermal conditions in this direction.

Model of the protective clothing and experimental stand (O – the origin of the coordinate system, Tc, Th, Ti, Tp, Ts and Tw are temperatures of the cooling water, external heat source, interfaces between the fabric layers and air gaps, the internal surface of the plate, the right external surface of the plate and the left external surface of the clothing, respectively)

2.1 Heat and mass transfer in the fabrics and air gaps as well as heat transfer in the plate

Convection in the hygroscopic porous fabrics and in the air gaps as well as presence of free liquid water in the fabric were neglected with only the liquid water bound by the fibres considered. Additionally, the clothes were assumed to contain humid air (dry air was stationary, water vapour might diffuse) and to be semi-transparent. Then the energy equation in the protective garment can be written in the following form:

where: the first term on the right hand side accounted for heat conduction in the fabrics or air gaps, the second one for heat transfer associated with diffusion of the water vapour in the fabrics and air gaps, the third one for heat absorbed (released) during transition of the water vapour into liquid water bounded in the fibres in fabrics, while the fourth one for thermal radiation in the fabrics (the air was transparent).

The continuity equation for the bound water in the fibres (describing sorption and desorption phenomenon) was expressed as:

while diffusion of the water vapour through the pores and air gaps and its phase transition to or from the bounded state was modelled by following equation:

The energy equation for the conductive heat transfer in the aluminium plate was given in the form:

The respective symbols in Eqs. (1)–(4) denote: cp – specific heat at constant pressure, Def – effective mass diffusivity, kef – effective thermal conductivity, qr – radiative heat flux, T – temperature, Δhabs – heat of desorption, Δhvap – heat of vaporization, ε – volume fraction, ρ – density and (ρc)ef – effective heat capacity. The sum of volume fractions satisfied the following constraint: εbw+εf+εg = 1 or εg = εa+εv = 1 in the fabrics or in the air gaps, respectively. In the equations above the subscripts: a, bw, f, g, p, w, and v correspond to: dry air, bound water, dry fabric, moist air, plate, liquid water and water vapour, respectively. The relation for the mass rate of transition of moisture from the bounded to gaseous states in the fabric layers was assumed as: \( {\dot{m}}_{v- bw}={D}_f{\uprho}_f/{d}_f^2\left({R}_{f, eq}-{R}_f\right) \), where: df was the average fibre diameter, Df – effective diffusivity of bound water in the solid phase (fibres), Rf – fibre regain and Rf,eq – equilibrium fibre regain. More details related to calculations of effective properties and other quantities in Eqs. (1)–(4) can be found in [5, 6, 15,16,17].

2.2 Radiative heat transfer

The clothing was assumed semi-transparent and non-grey. Therefore, distribution of spectral radiative intensity was given by the following radiative transfer equation [22,23,24,25]:

where: I is the radiation intensity, Ib – blackbody intensity [22], Ka and Ks – linear absorption and scattering coefficients, respectively, s – radiation path, s – direction vector, λ – wavelength, Φ – scattering phase function and Ω – solid angle.

2.3 Boundary, interface and initial conditions

The external and internal interfaces were considered either transparent, e.g., diffusively reflecting and transmitting or semi-transparent, i.e., absorbing, emitting and diffusively reflecting and transmitting for the incident thermal radiation. The plate surface was assumed opaque and diffusive. The boundary conditions at the external and internal surfaces of the system for balances of energy, Eqs. (1) and (4), as well as for the balance of water vapour, Eq. (3), took the following form:

-

The left external surface (see Fig. 1):

Considering two optical types of the interfaces the conditions for radiation intensity at the left external surfaces (for s⋅nf > 0, where: nf is the inward normal vector at the interface) and sum of net radiative heat fluxes were assumed as:

-

For the transparent interface

-

For the semi-transparent interface:

-

The interface between the fabric layers and air gaps or between two fabric layers if there is no air gap (where: L and R denote the left and right side of the interface, respectively):

For transparent or semi-transparent interfaces between the fabric layers and air gaps or between two fabric layers radiation intensities (for s⋅nL > 0 and s⋅nR > 0, where: nL and nR are the inward normal vectors at the interface) and sum of net radiative heat fluxes were following:

-

For the transparent interface:

and

-

For the semi-transparent interface:

and

-

The internal surface of the plate (where: L denotes the left side of the interface, i.e., either the air in the gap or the fabric):

For the opaque and diffusive internal surface of the plate radiation intensity (for s⋅np > 0, where: np is the inward normal vector at the interface) and net radiative heat flux were expressed as:

-

The right external surface of the plate:

The external convective and radiative heat fluxes in Eqs. (6), (8)–(11) were given by the following relationships:

and

In the above equations subscripts and superscripts: a, c, e, f, h, i, in, p, s, w, L and R denote the air, cooling water, surroundings, fabric, hot gases or source of thermal radiation, interface, incident, internal surface of the plate, external surface of the plate, clothing external surface, left and right side of the interface, respectively, while Eb is the blackbody emissive power [22], h and hm – convective heat and mass transfer coefficients, respectively, n – refractive index, q – heat flux, r – hemispherical surface reflectivity [22, 25, 26] (for transparent interface r was found by averaging the Fresnel reflectivity over the hemisphere), respectively, t – hemispherical surface transmissivity and ε – surface emissivity.

The unknown interface temperatures: Tw, Ti, Tp and Ts as well as water vapour densities: ρv,w, ρv,i and ρv,p were calculated from Eqs. (6), (12), (18) and (22) as well as Eqs. (7), (13) and (19), respectively. The boundary conditions at the external and internal interfaces for the radiative transfer equation, Eq. (5), were given by either Eqs. (8), (14a, 14b) and (20) or (10), (16a, 16b) and (20). The Eqs. (8) and (14a, 14b) assumed diffusive reflection and transmission of the incident radiation due to different values of refractive index on both sides of interfaces, while Eqs. (10) and (16a, 16b) emission and diffusive reflection and transmission of the incident radiation. For more details see [24,25,26]. Initial conditions for Eqs. (1)–(4) corresponded to the steady state distributions of temperature, volume fraction of the bound water and water vapour density in the whole system which was in contact only with the surroundings at temperature Te and relative humidity ϕe.

3 Numerical solutions

The energy, mass balance and radiative transfer Eqs. (1)–(5) were discretized applying the Finite Volume Method [27]. The Eqs. (1)–(4) were integrated over infinitesimal distance dx and time interval dt, while the radiative transfer equation over infinitesimal distance dx, solid angle dΩ and bandwidth dλ. The unknown temperatures at the external and internal interfaces were calculated from the non-linear conditions given by Eqs. (6), (12) and (18) by using iterative algorithm based on the Newton-Raphson Method [28], while the water vapour densities at these walls were found from discretized mass balance conditions described by Eqs. (7), (13) and (19). The Band Model [22] accounted for spectral optical properties. All equations were coupled and highly non-linear, therefore for the solution of the system of equations special in-house iterative algorithm was developed and implemented in the programming language C. The general flowchart of the computational algorithm is presented in Fig. 2.

4 Data for simulations

4.1 Model setup for verification analyses

The verification analyses (subsection 5.1) were performed assuming the data listed below. These parameters were based on values presented in the literature [3, 5, 6, 15,16,17]. The dimensions of the clothing layers are given in Table 1. Thermophysical properties of the fabrics are presented in Table 2, while Tables 3 and 4 contain optical properties for the grey and non-grey fabrics, respectively. Additionally, the isotropic scattering with the scattering albedo equal to ω = 0.5 was assumed in the all textile layers as all fibrous materials exhibit substantial scattering [22]. Other required material properties, boundary and operating parameters were assumed as [5, 6, 15,16,17]: ρw = 998.2 kg/m3, cw = 4185 J/kg/K, kw = 0.5984 W/m/K, kv = 0.018 W/m/K, Tc = 32°C, Te = 26°C, p = 101,325 Pa, ϕe = 0.6, εe = 1.0, εh = 0.15, he = 15 W/m2/K, hh = 0 W/m2/K and hm = 0.021 m/s. The plate thickness was Lp = 0.012 m and was made of aluminium of the following properties: ρp = 2800 kg/m3, cp = 913 J/kg/K, kp = 165 W/m/K and εp = 0.1. The plate was convectively cooled by water at Tc = 32°C and with hs = 100 W/m2/K. During verification analyses the protective clothing was exposed to the external radiative heat flux of qtotal = εhσTh4 = 20, 40 and 80 kW/m2. These values corresponded to the following temperatures of the external radiative heat source: Th = 1237.79, 1471.99 and 1750.50 K, respectively. The exposure time varied between te = 4 and 30 s. After the initial heating the system was cooled down in the ambient air at temperature Te and relative humidity ϕe.

4.2 Model setup for validation analysis

The data for validation analysis were assumed basing on measurements of selected thermophysical properties of the fabrics [29] and on information about conditions during experimental measurements in which the multi-layer protective clothing was exposed to the radiative heat flux emitted by the IR lamp [30, 31]. The other missing parameters, e.g., these related to the moisture transport and thermal radiative heat transfer were estimated either from extensive literature studies [3, 5, 6, 15,16,17, 32, 33] or based on the information from manufactures of the clothing and fabrics used in the experiments [32]. In Table 5 geometrical configuration and dimensions of the multi-layer protective clothing used in the experiments were given. It consists of four fabric layers (outer shell, moist barrier and thermal insulation integrated with liner) and three air gaps. The Table 6 contains thermophysical properties of the fabrics, while the non-grey optical properties of the clothing are presented in Table 7. Unfortunately, the detailed optical properties of the selected materials were unknown, therefore they were estimated using the simplified Bamford and Boydell’s method [17, 33]. In this approximation calculation of the spectral transmissivity Tλ,f of each textile layer required only its specific mass. Moreover, the fabric reflectance was fixed to Rλ,f = 0.245 for all wavelengths and fabrics [17]. Then the spectral extinction coefficients of the i-th fabric layer was calculated using the following relationship [33]: Ke,λ,f,i = −ln[(1−Rλ,f,i)/Tλ,f,i)/Lf,i, where Lf,i is the thickness of i-th fabric layer. The other parameters were assumed as follows: Te = 28.5°C, εh = 0.0, he = 6.0 W/(m2 K), εp = 0.05 and hs = 250 W/m2/K. During simulations radiative heat flux emitted by the IR lamp and reaching the clothing was qtotal = 20 kW/m2, while the exposure time was te = 32.5 s. These values were measured in the experiment [32]. After the initial heating the clothing was cooled down in the ambient air. Other, not mentioned here, optical and thermophysical properties as well as values of parameters at boundaries were the same as these listed in the section 4.1.

4.3 Default discretization levels

During the simulations default discretization levels were as follows:

-

Spatial: each fabric layer and air gap as well as the plate were divided into Nl = 25 elements.

-

Angular: the polar and azimuthal angles were divided into Nθ×Nφ = 2×4 control angles.

-

Time: the time step was kept at Δt = 0.05 s.

-

Wavelength: discretisation depends on assumed number of bands and varied from case to case.

5 Results of simulations

5.1 Verification

5.1.1 Influence of discretization levels

In the first step of verification of the developed model the influence of spatial, time, angular and wavelength discretization levels on the obtained results were investigated, i.e., discretisation convergence tests were carried out. Simulations were performed for the multi-layer protective clothing presented in Fig. 1 (three fabric layers and three air gaps) and for three values of the incident radiative heat flux equal to qtotal = 20, 40 and 80 kW/m2 as well as for three exposure times equal to te = 10, 20 and 30 s. Other material properties and parameters assumed during the simulations were described in the section 4.1.

The first calculations were executed for variable numbers of nodes in the spatial domain. Each layer of the system was divided into Nl = 12, 25 and 50 elements. All together three meshes of Ns = 84, 175 and 400 nodes were generated. The distributions of temperature in the clothing, air gap and in the front part of the aluminium plate for exposition time te = 20 s and for the variable incident radiative heat flux, i.e., qtotal = 20, 40 and 80 kW/m2 just after the heating period as well as after 10 and 20 s of the cooling stage in the surroundings are presented in Fig. 3. For clarity only the results for the clothing, the wide air gap and the front part of the plate (2 mm) are given. More detailed views of temperature distributions but only across the multi-layer clothing are presented in Fig. 4. At the end of the exposition to the incident radiative heat flux temperature of the left boundary of the system increased significantly due to external heating of the clothing. The value of maximum temperature in the system increased with rise in the value of incident radiative heat flux. Then the clothing was cooled down. Heat was transferred both to the surroundings (by convection and thermal radiation) and to the aluminium plate which imitated the human body (by conduction and thermal radiation). Therefore, peaks of temperature appeared in the clothing for the cooling period. Moreover, the results obtained for different meshes match each other very well – see Figs. 3 and 4. Small discrepancies between the results for different grids are observed in the largest air gap. The source of them is probably temperature dependent thermal conductivity of the air. In the numerical model the thermal conductivity was calculated for nodal values of temperature instead of averaged over the mesh element.

Distributions of temperature in the clothing, air gap and in the front part of the aluminium plate for te = 20 s and for: a) qtotal = 20 kW/m2, b) qtotal = 40 kW/m2 and c) qtotal = 80 kW/m2 just after the heating period as well as after 10 and 20 s of the cooling stage in the surroundings for different spatial meshes

Next studies were performed for the various time steps. Three values were considered: Δt = 0.025, 0.05 and 0.1 s. It was found that decreasing or increasing of the time step had negligible effect on the results obtained, e.g., relative differences between temperature distributions calculated for two different time steps were below 0.1% for all analysed cases.

Subsequently influence of the angular discretization levels were studied. Four divisions of the polar and azimuthal angles were considered: Nθ×Nφ = 2×4, 4×4, 4×8 and 8×8. It was observed that increasing polar angle discretization from Nθ = 2 to 4 and from 4 to 8 had minor effect on relative differences between temperature distributions in the clothing obtained for two different polar angle divisions, but changing the azimuthal angle division from Nφ = 4 to 8 resulted in the greatest relative difference reaching up to 4% between temperature distributions calculated for two different azimuthal angle discretizations. This effect is related to rise in accuracy of calculations of thermal radiation with increasing of the angular discretization level. For the larger number of discrete direction the ray effect is reduced.

Finally influence of the number of radiation bands considered was studied. Simulations were performed for the number of bands equal to: Nb = 1, 4 and 8. Each band had the same constant optical properties which were defined in Table 3. It was found that the number of bands did not affect the obtained results.

5.1.2 Conductive-radiative heat transfer in the single- and multi-layer clothing system

Consecutively, the part of the numerical simulator responsible for calculations of conjugated conductive and radiative heat transfer with the moisture transport neglected was verified by comparing predicted temperature distributions with the results obtained by applying the commercial code ANSYS Fluent. At first the system which consisted of a single fabric layer (layer I, outer shell – for properties see Tables 1 and 2), the wide air gap and the plate was considered. The fabric was assumed to have the non-grey properties with the spectral absorption and scattering coefficients given in Table 4, while the refractive index was the same in each band and was presented in Table 3. Additionally, the outer fabric surface was assumed opaque (εw = 0.9), while the inner one transparent to the thermal radiation. The system was convectively heated for te = 4 s by hot gases at Th = 1400.0 K and with hh = 120.0 W/m2/K. Later the clothing was convectively and radiatively cooled down in the surroundings at Te = 26°C and with he = 15 W/m2/K. Other parameters were defined in section 4.1. The obtained distributions of temperature in the system just after the heating period as well as after 5 and 10 s of the beginning of the cooling stage are presented in Fig. 5a. The detailed view of the temperature in the clothing is shown in Fig. 6a. The thermal radiation heated the left boundary of the clothing which resulted in the significant increase of temperature. Then in the cooling period heat was transferred in both directions to the surroundings (by convection and thermal radiation) and to the aluminium plate (by conduction and thermal radiation). This resulted in the small peaks of temperature which were found in the fabric layer. These peaks were shifted to the clothing interior because the intensity of heat transfer to the surroundings was higher than to the plate. Moreover, perfect matching of the predictions obtained applying the present model with results attained from the ANSYS Fluent was observed. Relative difference between the results was found to be below 1%.

Comparison of temperature distribution in the a) single-layer and b) multi-layer clothing as well as in the air gap and plate just after the heating period (t = te) as well as after 5 (t = te + 5) and 10 s (t = te + 10) of the cooling stage in the surroundings (PM – present model, Ref. – ANSYS Fluent)

The next comparison was performed for a system which consisted of the multi-layer protective clothing (three fabric layers separated by the thin air gaps), the wide air space and the aluminium plate – see Fig. 1. The boundary conditions at the outer clothing surface and at the internal surfaces between fabric layers and air gaps were assumed the same as in the previous simulation. The clothing configuration and thermophysical data assumed during simulations were given in Tables 2 and 3. Additionally, the fabrics were treated as the non-grey with the same values of optical properties in each layer (Table 4) and with wavelength independent refractive index (Table 3). Other parameters were defined in section 4.1. Again very good agreement between the results from the present numerical simulator and from the commercial code can be noticed in Figs. 5b and 6b. This time the relative difference between the results from the in-house and commercial software were below 2%. Moreover, the peaks of temperature in the multi-layer clothing were observed during the cooling period, but the source of them was the same as in the previous cases. These peaks were higher than for the single clothing layer due to higher thermal resistance to heat flow for the multi-layer clothing than for the single fabric.

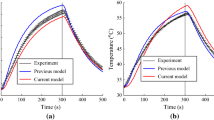

5.2 Validation

In the validation analysis the simulated temporal variations of temperature at the outer (i.e., between the surroundings and the first fabric layer) and inner (i.e., between the last fabric layer and the widest air gap) surfaces were compared with the respective temperature variations obtained experimentally [30, 32] – see Fig. 7. The four layer protective clothing with the thermophysical and optical properties described in section 4.2 was considered. The other parameters necessary to carry out simulations were also given in this section. The simulated and measured temperature variations are not ideally consistent. But having in mind complexity of the proposed model one can notice that the model predicted thermal behaviour of the considered protective clothing quite reasonably. Values and time of occurrence of the maximum temperatures at the outer and inner side of the clothing are foreseen very well. Moreover, the simulated temperature increase during heating period on both considered surfaces corresponds well to these measured during experiment. The most significant discrepancies between the results obtained from the numerical simulations and measurements are observed during the cooling period. These differences may result from:

-

Improper estimation of thermophysical and optical properties of the clothing layers as the non-grey optical properties were not measured but instead were evaluated using the Bamford and Boydell’s method [33].

-

Large number of input material parameters of the model. Some of them were difficult to estimate and were assumed arbitrary basing on the available literature data.

-

Neglecting of some phenomena, e.g., heat convection in the porous clothing or chemical reaction in the fabrics which may lead to changes in the fabric properties and structure.

-

Neglecting temperature variation of thermophysical and optical properties of the fabrics.

Comparison of the predicted and measured temporal variation of temperatures at the a) outer and b) inner surfaces of the protective clothing (Experiment – data from [32], PM – present model)

Another source of differences between the simulated and measured temperatures may be incorrect assessment of the initial and boundary conditions. The performed experiments were not typical validation experiments [34]. Therefore, the initial and boundary conditions were not strictly controlled during them.

6 Conclusions

The paper presents credibility analysis of the novel advanced numerical simulator of heat and mass transfer in the multi-layer protective clothing and in the elements of the experimental stand subjected to either high temperature environment or high incident radiative heat flux emitted by hot objects. The developed numerical model accounted for conjugated conductive and radiative heat transfer in the hygroscopic and non-grey porous fabrics and in the transparent air filling the gaps as well as conductive heat transfer in the opaque components of the stand. Moreover, diffusion of the water vapour in the pores and air spaces as well as phase transition of the bound water in the fabric fibres (sorption and desorption) were included. Complex energy and mass balance as well as optical conditions between the clothing layers were formulated in order to find the values of temperature, vapour density and radiation intensity at these interfaces. The obtained highly non-linear coupled system of discrete equations was solve by the in-house iterative numerical algorithm which was based on the Finite Volume Method. Additionally, the unknown temperatures at the external and internal interfaces were calculated using the Newton-Raphson Method, while the Band Model accounted for spectral optical properties.

Subsequently, the correctness and accuracy of the results predicted by the developed model were assessed. At first influence of the spatial, time, angular and wavelength discretization levels on the obtained solutions were investigated. No problems were detected. Despite different discretization levels the results obtained were close to each other. Then, the part of the solver responsible for calculations of transient conductive and radiative heat transfer in the fabrics with the non-grey optical properties and other elements of the system was verified. In these simulations moisture transport was neglected. Two clothing configurations, i.e., the single- and multi-layer were studied. Afterwards the results obtained were compared with the ANSYS Fluent predictions and very good agreement was observed. Finally the simulated and measured temporal variation of temperature at the outer and inner surfaces of the multi-layer protective clothing were compared. The presented numerical model predicted the increase in temperature during the heating period quite well. Greater discrepancies were observed during the cooling stage for which the model underestimates the temperature variation at the outer and inner surfaces. The source of these differences may be related to, e.g., improper estimation of thermophysical and optical properties of the clothing layers, neglecting of some phenomena and drawbacks in validation character of the carried experiments. Having in mind that the developed model requires large number of input parameters the matching of the predicted and measured results seems satisfactory.

References

Torvi DA, Dale JD (1999) Heat transfer in thin fibrous materials under high heat flux. Fire Technol 35:210–231

Torvi DA, Threlfall TG (2006) Heat transfer model of flame resistant fabrics during cooling after exposure to fire. Fire Technol 42:27–48

Mell WE, Lawson JR (2000) A heat transfer model for firefighters’ protective clothing. Fire Technol 35:39–68

Song G, Barker RL, Hamouda H, Kuznetsov AV, Chitrphiromsri P, Grimes RV (2004) Modeling the thermal protective performance of heat resistant garments in flash fire exposures. Text Res J 74:1033–1040

Chitrphiromsri P, Kuznetsov AV (2005) Modeling heat and moisture transport in firefighter protective clothing during flash fire exposure. Heat Mass Transf 41:206–215

Song G, Chitrphiromsri P, Ding D (2008) Numerical simulations of heat and moisture transport in thermal protective clothing under flash fire conditions. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 14:89–106

Ghazy A, Bergstrom DJ (2010) Numerical simulation of transient heat transfer in a protective clothing system during a flash fire exposure. Numer Heat Tr A 58:702–724

Ghazy A, Bergstrom DJ (2012) Numerical simulation of heat transfer in firefighters' protective clothing with multiple air gaps during flash fire exposure. Numer Heat Tr A 61:569–593

Zhu F, Li K (2011) Numerical modeling of heat and moisture through wet cotton fabric using the method of chemical thermodynamic law under simulated fire. Fire Technol 47:801–819

Zhu F, Zhang W, Song G (2008) Heat transfer in a cylinder sheathed by flame-resistant fabrics exposed to convective and radiant heat flux. Fire Saf J 43:401–409

Jiang YY, Yanai E, Nishimura K, Zhang H, Abe N, Shinohara M, Wakatsuki K (2010) An integrated numerical simulator for thermal performance assessments of firefighters’ protective clothing. Fire Saf J 45:314–326

Fu M, Yuan MQ, Weng WG (2015) Modeling of heat and moisture transfer within firefighter protective clothing with the moisture absorption of thermal radiation. Int J Therm Sci 96:201–210

Udayraj TP, Das A, Alagirusamy R (2017) Numerical modeling of heat transfer and fluid motion in air gap between clothing and human body: effect of air gap orientation and body movement. Int J Heat Mass Transf 108:271–291

Udayraj TP, Das A, Alagirusamy R (2017) Numerical investigation of the effect of air gap orientations and heterogeneous air gap in thermal protective clothing on skin burn. Int J Therm Sci 121:313–321

Łapka P, Furmański P, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Numerical modelling of transient heat and moisture transport in protective clothing. J Phys Conf Ser 676:012014

Łapka P, Furmański P (2017) Zastosowanie dwurównaniowego modelu transportu ciepła w skórze do oceny charakterystyk cieplnych ubrań ochronnych (application of a biequational bioheat transfer model in the skin for assessment of thermal characteristics of protective garments). Przem Chem 96:343–347 (in Polish)

Łapka P, Furmański P, Wiśniewski TS (2017) Assessment of thermal performance of protective garments. The advanced numerical model Int J Numer Methods Heat Fluid Flow 27:1078–1097

Łapka P, Furmański P, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Analysis of influence of different heat transfer modes on temperature distribution in the protective clothing and skin. Procedia Eng 157:72–81

Łapka P, Furmański P, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Comparison of different bioheat transfer models for assessment of burns injuries. AIP Conf Proc 1790:070002

Furmański P, Łapka P (2017) Evaluation of a human skin surface temperature for the protective clothing-skin system based on the protective clothing-skin imitating material results. Int J Heat Mass Transf 114:1331–1340

Łapka P, Furmański P (2016) An advanced model of heat and mass transfer in the protective clothing – verification. J Phys Conf Ser 745:032075

Howell JR, Siegel R, Mengüç MP (1992) Thermal radiation heat transfer. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Łapka P, Furmański P (2010) Fixed Cartesian grid based numerical model for solidification process of semi-transparent materials I: modelling and verification. J Heat Transf 132:023504

Łapka P, Furmański P (2012) Fixed Cartesian grid based numerical model for solidification process of semi-transparent materials I: modelling and verification. Int J Heat Mass Transf 55:4941–4952

Łapka P, Furmański P (2012) Fixed Cartesian grid based numerical model for solidification process of semi-transparent materials II: reflection and refraction or transmission of the thermal radiation at the solid–liquid interface. Int J Heat Mass Transf 55:4953–4964

Seredyński M, Łapka P, Banaszek J, Furmański P (2015) Front tracking method in modeling transport phenomena accompanying liquid-solid phase transition in binary alloys and semitransparent media. Int J Heat Mass Transf 90:790–799

Versteeg HK, Malalasekera W (2007) An introduction to computational fluid dynamics. Pearson Education Ltd, Harlow

Ferziger JH, Peric M (2002) Computational methods for fluid dynamics. Springer, Berlin

Pietrak K, Kubiś M, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Badanie właściwości cieplnych materiałów ochron osobistych (measurements of thermophysical properties of materials for protective clothing). Zeszyty Naukowe SGSP 58:173–192 (in Polish)

Bugaj MA, Cieślikiewicz Ł, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Badania materiałów odzieży ochronnej będącej w kontakcie z ciałami o podwyższonej temperaturze (investigation of protective clothing materials being in contact with hot bodies). Zeszyty Naukowe SGSP 58:149–171 (in Polish)

Roguski J, Błogowski M, Kubis D (2015) Testing methods used to evaluate the endurance of personal protective clothing against external thermal influences. Safety and Fire Technique 39:43–57

Łapka P, Furmański P, Bugaj MA, Cieślikiewicz Ł, Pietrak K, Kubiś M, Wiśniewski TS (2016) Walidacja modelu przepływu ciepła i wilgoci przez ubiór ochronny (validation of heat and mass transfer model in the protective clothing). Zeszyty Naukowe SGSP 58:231–251 (in Polish)

Bamford GJ, Boydell W (1995) ICARUS: a code for evaluating burn injuries. Fire Technol 31:307–335

Banaszek J (2005) Credibility analysis of computer simulation of complex heat transfer problems. Conference Proceedings of the Numerical Heat Transfer 2005 – Eurotherm Seminar No. 82, 1:141–161

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Centre for Research and Development (Poland) under Grant No. O ROB/0011/03/001 and by the Faculty of Power and Aeronautical Engineering of Warsaw University of Technology in the framework of statutory activity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Łapka, P., Furmański, P. Verification and validation of an advanced model of heat and mass transfer in the protective clothing. Heat Mass Transfer 54, 2461–2474 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-018-2337-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-018-2337-z