Abstract

Background

Age is a major risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) and death, but there has been a debate about benefit-risk of statin treatment in the elderly with limited evidence on benefits for primary prevention, while there is strong evidence for its use in secondary prevention.

Aim

The aim of this study was to provide an overview of statin utilization in primary and secondary prevention for patients 75–84 years and ≥ 85 years in the Swedish capital Region Stockholm in 2019.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study based on the regional healthcare database VAL containing all diagnoses and dispensed prescription drugs for all 174,950 inhabitants ≥ 75 years old in the Stockholm Region. Prevalence and incidence were analyzed by sex, age, cardiovascular risk, substance, and the intensity of treatment.

Results

A total of 35% of all individuals above the age of 75 in the region were treated with statins in 2019. The overall incidence in this age group was 31 patients per 1000 inhabitants. Men, individuals 75–84 compared to ≥ 85 years of age, and those with higher cardiovascular risk were treated to a greater extent. Simvastatin was used primarily by prevalent users and atorvastatin by incident users. The majority was treated with moderate-intensity dosages and fewer women received high intensity treatment.

Conclusions

Statins are widely prescribed in the elderly. Physicians seem to consider individual cardiovascular risk when deciding to initiate statin treatment for elderly patients, but here may still be some undertreatment among high-risk patients (especially women and elderly 85 + years) and some overtreatment among patients with low-risk for CVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aging populations and increased survival rates from myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke have increased the need for cardiovascular prevention [1]. There is strong evidence that statins reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [2, 3]. However, most studies have included younger patients, and the number of patients above the age of 75 years has been limited. Current guidelines may not be so well suited for elderly patients with cardiovascular risk and many other concomitant diseases and drugs [3,4,5], and the benefit-risk ratio for statin treatment in the elderly has been a subject of debate [6].

There is solid evidence of beneficial effects of statin treatment for secondary prevention in elderly patients. A meta-analysis (CTTC) from 2019 showed a significant risk reduction for cardiovascular events among elderly ≥ 75 years with established CVD treated with statins [7]. Statins are thus indicated for elderly patients with high cardiovascular risk, including those with a prior myocardial infarction (MI), ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke/TIA, or peripheral atherosclerotic disease (PAD). Consequently, current European guidelines recommend statins for secondary prevention in the elderly [3, 4].

The evidence for a favorable benefit-risk ratio for primary prevention with statins in the elderly is less robust and mainly based on subgroup analyses of small RCTs [8,9,10,11] or observational studies. Some observational studies have shown risk reductions of the same magnitude or even greater than for younger patients [12,13,14,15,16], but there are also observational studies showing limited benefit of statin treatment for primary prevention in elderly individuals with and without diabetes [17, 18]. In a meta-analysis of 28 RCTs published in 2019, no significant cardiovascular risk reduction was shown for primary prevention among the 8% elderly patients > 75 years (RR 0.92; 99% KI 0.73–1.16) [7]. The significant trend towards smaller proportional risk reductions with increasing age remained even after exclusion of 4 studies on heart failure and kidney dialysis (where statins have not been shown to be effective) [7].

Current guidelines suggest that statin treatment in the elderly should be based on individual benefit-risk assessments, taking age, risk for adverse drug reactions (ADRs), comorbidities, polypharmacy, drug-drug interactions, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics as well as patient preferences into account.

Statins are in general well tolerated and double blind RCTs have shown low frequencies of ADRs which indicates that tolerability problems partly reflect patient expectations [2, 19]. Muscular symptoms are the most common ADRs and, e.g., in the PRIMO observational study 10.5% of all patients treated with statins reported myalgia [20]. However, there is a substantial nocebo-effect, and according to the SAMSON study, similar symptom intensity was experienced among participants during statin treatment compared to placebo treatment [21]. Furthermore, no difference was found between statin and placebo in terms of symptom intensity at start and extent of symptom relief at discontinuation [21]. This indicates that many patients experience side effects linked to taking tablets rather than the tablet containing a statin. Other ADRs include the development of diabetes, but this risk is very low [2]. There is no evidence that statin have any negative impact on cognition [22], and according to the PALM study, statins have similar tolerability in older and younger patients [23].

The debate has been intense among professional societies and the general public on the value of treating elderly patients with statins. Limited evidence of the beneficial effect in primary prevention, potential problems of poor medication adherence, drug–drug interactions, and side effects that could negatively impact quality of life have fueled this debate. There is limited knowledge on how this is reflected in the prescribing patterns of physicians and to what extent elderly with different cardiovascular risk profiles are treated with statins today. The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the use of statins in primary and secondary prevention for elderly (≥ 75 years) and very old (≥ 85 years) patients in the Stockholm Region in 2019. We specifically assessed if there were any differences in incidence and prevalence of statin treatment, and choice of drug and dose by age, sex, and cardiovascular risk profile of the patients.

Methods

Study design and population

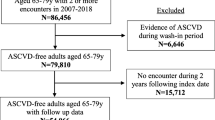

This was a cross-sectional study based on registry data on dispensed prescription drugs and recorded diagnoses in primary and secondary care for all individuals over the age of 75 in the Swedish capital region of Stockholm.

Data sources

Data were collected from the administrative healthcare database VAL held by the regional health authority in Stockholm [24]. VAL contains information about all hospitalizations and specialist ambulatory care consultations in the region since 1993 (with more than 99% coverage), and all primary care consultations since 2003 (with more than 85% coverage of diagnoses). The database also contains demographic information on patient age, sex, migration, and death. For each healthcare contact, the VAL database contains a record of the provider unit, an encrypted patient identification number, age and sex, the type and length of the stay, and up to ten diagnoses. Since 1997, diagnoses are coded according to the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). Since July 2010, information on dispensed prescription drugs is also included in the database. These data originate from the same data source as the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register with a population coverage of over 99% [25]. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system is used to classify different drugs [26].

For this study, we extracted all dispensed prescriptions of statins (ATC C10AA) to residents in the Stockholm Region at any pharmacy in the country during 2018 and 2019, respectively, and linked this with information on diagnoses reported in primary care, specialist ambulatory care and inpatient care during the years 2015–2019, using the unique patient identifiers for each patient [27]. Data on dispensed prescriptions included age and sex of the patient, dispensing date, information about the dispensed drug (substance, ATC-code, formulation, and strength), and the specialty of the prescriber.

The diagnoses included in the study were MI (ICD I21, I22, I24.1, and I25.2), IHD (I20, I24 excl. I24.1, and I25 excl. I25.2–4), stroke/TIA (G45, G46, I63-I66, and I69.3–4), PAD (I70, I71, I73.9, I74, and K55), diabetes mellitus (E10, E11), and hypertension (I10).

Data analyses

Analyses were conducted for incident and prevalent statin users. The first prescription dispensed in 2019 was selected to identify substance and strength in all analyses. Prevalence was calculated as the proportion of all elderly living in the Region (January 1, 2019) who purchased at least one prescription of a statin during 2019 and presented as a number of patients/1000 inhabitants. To calculate incidence, a washout period of one year was applied, i.e., patients without any dispensing in 2018. Incidence was defined as the proportion of all people in the Region who claimed their first prescription and presented as a number of patients/1000 person-years.

Age was classified into two groups: 75–84 vs. 85 and above. Sex was classified as men and women. A diagnosis hierarchy developed by Wallach Kildemoes et al. was applied to manage cardiovascular comorbidity in the analyses of cardiovascular risk [28]. In this approach, each individual is classified based on the highest ranked diagnoses reported during the previous five years. The diagnosis hierarchy applies the following ranking of diagnoses: MI (1), IHD (2), stroke/TIA (3), PAD (4), diabetes (5), hypertension (6), and none of these diagnoses (7).

Four different statins were available on the Swedish market at the time of the study: atorvastatin (C10AA05), simvastatin (C10AA01), rosuvastatin (C10AA07), and pravastatin (C10AA03). Their dose intensities were classified as low, moderate, or high (Table 1).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive data are presented as numbers and proportions of patients and as means and ranges. Data management and analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 [SAS Institute, Cary, NC] and Microsoft Excel 2016.

Results

During 2019, the region had 128,627 inhabitants aged 75–84 and 46,323 inhabitants over the age of 85, corresponding to 5 and 2%, respectively, of the total population (all ages) in the region (Table 2). There were more women than men in both age groups (55% among 75–84 years and 66% among 85 + years of age). The overall cardiovascular risk was higher among men compared to women in both age groups (Table 2).

Prevalence and incidence of statin treatment

A total of 35% of all elderly in the region were treated with statins in 2019. The lowest proportion was observed among women over the age of 85 with 25% (247 patients/1000 inhabitants) and the highest among men 75–84 years of age with 43% (427 patients/1000 inhabitants) (Fig. 1). The overall incidence was 31 elderly patients per 1000 inhabitants, ranging between 20 and 37 per 1000 inhabitants. Thus, 3% of the total elderly population or around one tenth of the prevalent users were initiated during 2019 (Fig. 1). More men were dispensed and initiated on statins in both age groups.

Among those 75–84 years of age with an identified cardiovascular risk, the utilization of statins was highest among those who had a history of MI and lowest among those with hypertension (Fig. 2). One tenth (9.8%) of the elderly without a previously registered cardiovascular diagnosis received statin treatment in 2019. The proportions were 11 and 10% among men and women aged 75–84 and 9 and 6% among men and women older than 85, respectively.

Cardiovascular risk among elderly patients treated with statins

The largest proportion of all women 75–84 years of age who were dispensed statins during 2019 (34%) had only hypertension as a cardiovascular risk factor. Among men of the same age, 21% had only hypertension while an equally high proportion had a history of MI. Among those aged 85 + , hypertension alone was still most common (28%) among women, while a history of MI (alone or in combination with other risk factors) was most common (27%) among men (Table 3).

In total 53% of all men and 38% of all women aged 75–84 years received statins for secondary prevention. Corresponding figures for those older than 85 were 66% and 54% of all men and women, respectively. The proportion treated for secondary prevention was slightly higher among patients initiated on treatment (Table 3).

Choice of statin and dose intensity

Simvastatin was the most common statin among prevalent users in both sex and age groups (Fig. 3A) whereas atorvastatin was most common among incident users (Fig. 3B). Simvastatin was more common among the oldest than among those 75–84, but there were no sex differences in the choice of statins.

Most elderly patients of both sexes received statins with moderate intensity, but the proportion treated with high intensity for secondary prevention was higher among men (Fig. 4A). Low intensity treatment was more common in primary than in secondary prevention for both age groups, while the opposite was observed for high intensity treatment in both age groups (Fig. 4A).

Moderate intensity treatment was also most common among newly initiated patients in most patient groups except for men aged 75–84 treated for secondary prevention where a slightly higher proportion received high intensity treatment (Fig. 4B). Overall, low intensity was more commonly used in primary prevention and high intensity for secondary prevention, regardless of age and sex.

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study including all inhabitants over the age of 75 years in the Swedish capital region, we found 35% to be treated and 3% to be newly initiated on statin treatment in 2019. Men, individuals < 85 years and those with higher cardiovascular risk were treated to a higher extent. Simvastatin was prescribed primarily to prevalent users and atorvastatin to incident users. A majority were treated with moderate-intensity dosages and fewer women received high intensity treatment.

The prevalence shows treatment in relation to cardiovascular risk categories which reflects guidelines that have been in place for a long time, while the incidence reflects how physicians are currently reasoning around risk–benefit when initiating treatment for elderly patients. It is not surprising that statin treatment is common among the elderly given that atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic kidney disease and dyslipidemia increase by age [5, 30]. There are also several studies showing that the benefit of treating elderly patients with statins is similar to that of treating younger patients [7, 31, 32]. Relatively few elderly patients (3%) were initiated on statins in our study, but many high-risk patients were probably already treated.

We found that more men than women received treatment in all cardiovascular risk groups. Since large RCTs have shown similar beneficial effects of statin treatment in men and women, major gender differences should not be expected (CTC 2019). However, similar gender differences in utilization have been found in other studies, despite higher cholesterol levels among the women [33,34,35,36]. Several reasons for these inequities have been suggested. There is some evidence that cardiovascular disease is underdiagnosed in women [37]. Furthermore, in a meta‐analysis including more than 1.8 million elderly statin users in 13 countries, female sex was associated with increased nonadherence [38]. The latter may be attributable to more perceived adverse effects in women or limited motivation. More studies are needed to investigate reasons behind these gender differences.

Statin treatment was less common among the oldest, and few people over 85 years of age were initiated on treatment. This is in line with findings from other studies [39, 40]. It may reflect either that physicians consider the benefit-risk balance to be less favorable or that the oldest patients discontinue their treatment to a larger extent, but the latter seems less likely [38]. Many of the oldest (85 + years) are vulnerable with many other concomitant diseases and drugs that may interact with statins and increase the risk for adverse events [41]. Their life expectancy is less than for those 75–84 of age and, consequently, the benefits of treatment may be less pronounced [1]. Furthermore, results from a randomized study indicated that discontinuation of statin treatment during the last year of life may improve quality of life [42]. The sparsity of evidence calls for more studies on the effect and safety of statin treatment in the oldest patients [43] as well as qualitative studies investigating attitudes and beliefs about statins among physicians and patients [44, 45].

We found larger proportions of men and women with established CVD to be treated than those who received it for primary prevention (44–78% vs 16–39%), showing that statins are mainly prescribed to those with the largest potential benefit. Our findings indicate better adherence to guidelines than in other studies. A Canadian study showed that only 12% of patients aged 75–84 years and 6% of elderly 85 + without CVD received statins while 34% and 21%, respectively, with an indication for secondary prevention were treated [46]. It is impossible to determine what would be the optimal proportion treated at a population level without access to data on other risk factors such as lipids, smoking and BMI, as well as data on medication adherence in clinical practice. Our findings indicate that there is undertreatment of elderly patients with established CVD, while this is less certain for patients in primary prevention. The proportions of men and women with no risk marker for CVD who received statins in our study were rather small (6–11%). There may be several reasons why they received treatment, such as hypercholesterolemia without established CVD or a strong heredity for CVD. It is also important to acknowledge that even though we collected diagnoses from the entire healthcare system during five years, some patients may have comorbidities not being recorded as ICD-10 diagnoses. However, we cannot with the current data exclude that there is some overtreatment of low-risk patients with no clear indication for statin treatment. This was shown in a Finnish study where 11% of all patients ≥ 75 years of age with low risk received statin treatment [47].

Simvastatin was the most commonly prescribed statin among prevalent patients whereas atorvastatin was the most common choice for patients who were newly initiated. This is not surprising since simvastatin was recommended as first line drug during many years, due well-documented effects and a lower price as a generic drug compared to the other statins. While simvastatin lost its patent in 2002, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin were not generic until 2012 and 2016, respectively. Before the patent expiry for atorvastatin, regional guidelines recommended simvastatin and the Swedish reimbursement agency TLV only reimbursed atorvastatin and rosuvastatin for patients not reaching treatment targets with simvastatin [48, 49]. Thus, many elderly patients have probably been treated with simvastatin for many years without any need to change the therapy.

Moderate intensity dosages were most commonly used in the present elderly cohorts, in line with current recommendations. Older patients are more vulnerable to ADRs because of age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [50]. Furthermore, many elderly are concomitantly treated with other drugs that may interact with statins and increase the risk of ADRs [41]. Our findings are in concordance with the American PALM study showing that fewer elderly received high intensity treatment for secondary prevention (Nanna et al. 2018). The benefit of treatment to low LDL-targets in the elderly may also be questioned as there are both studies that support high intensity treatment in the elderly [51] and that show limited additional benefit [52].

Strengths and limitations

This study included all elderly inhabitants in an entire Swedish region. Data were collected from a regional data database of high quality with data on diagnoses and healthcare consultations from primary care, specialist ambulatory care and inpatient hospital care for all inhabitants in the region. Drug utilization patterns were assessed using complete data on all dispensed prescription drugs in the country regardless of reimbursement status or where in the country the patients claimed their prescriptions. We chose a five-year period for the identification of diagnoses as all patents do not have annual appointments with healthcare and diagnosis reporting may be incomplete at some visits. This was based on experience from previous research on patterns of diagnoses by us and others [24, 53,54,55,56].

We also acknowledge some limitations. Data on dispensed drugs may differ both from what is prescribed, i.e., the intention of the treating physician, and what is actually ingested by the patients. Statins that are purchased abroad are not included in the register but this is not common, and elderly patients may receive statin therapy without prescriptions when they are hospitalized. There might also have been some misclassification in our estimate of incidence based on a wash-out period of one year to identify new users. Furthermore, we only assessed the first prescription being dispensed during 2019 and previous studies have shown that many patients discontinue their treatment early during the therapy [56]. However, this may vary between settings and in a study of secondary prevention with statins in Stockholm we recently found primary non-compliance (not filling a prescription) in ≈ 20% of the patients but non-persistence was very uncommon once the treatment had been initiated [57]. The selection of the first prescription may have underestimated the use of high intensity treatment since some patients may be initiated on lower doses than the target dose used for long-term treatment. There may also be some misclassification in the reporting of diagnoses as previous studies using secondary databases have shown problems with over and under-reporting of diagnoses [58]. It is unlikely that we have overestimated the cardiovascular risk in our study. We used a five-year time window including all caregivers and diagnoses of MI and stroke and this has been shown to have a high validity [59]. There is, however, a potential that we underestimated the risk for some patients who had no consultations with reported diagnoses during this time window or who were treated abroad or at the very few private clinics not reporting data. Finally, we acknowledge that we only assessed prescribing patterns in relation to registered diagnoses since we had no data on other risk factors such as LDL cholesterol, heredity, renal function, smoking, alcohol, BMI, and physical activity.

Conclusion

This study showed that more than one third of all elderly, aged ≥ 75 years in the Swedish capital region of Stockholm, are treated with statins. The adherence to guidelines is rather high with most patients at high cardiovascular risk receiving evidence-based statin treatment with appropriate doses. Still, it is likely that there is undertreatment among high-risk patients (especially those with TIA/stroke, PAD, women, and the very old, 85 + years) and some overtreatment among patients with low-risk for CVD. Physicians seem to consider the patient’s cardiovascular risk when deciding to initiate statin treatment for the elderly.

Availability of data and materials

The pseudonymized patient-level data collected from regional registers are not allowed to share publicly due to confidentiality reasons; however, upon reasonable request, additional analyses can be conducted after contact with the corresponding author.

References

Strandberg TE (2019) Role of statin therapy in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in elderly patients. Curr Atheroscler Rep 21(8):28

Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Blumenthal R, Danesh J, Smith GD, DeMets D, Evans S, Law M, MacMahon S, Martin S, Neal B, Poulter N, Preiss D, Ridker P, Roberts I, Rodgers A, Sandercock P, Schulz K, Sever P, Simes J, Smeeth L, Wald N, Yusuf S, Peto R (2016) Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet 388(10059):2532–2561

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L (2020) 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 41(1):111–188

Stam-Slob MC, Visseren FLJ, Wouter Jukema J, van der Graaf Y, Poulter NR, Gupta A (2017) Personalized absolute benefit of statin treatment for primary or secondary prevention of vascular disease in individual elderly patients. Clin Res Cardiol 106(1):58–68

Stavropoulos K, Imprialos K, Doumas M, Athyros VG (2018) What is the role of statins in the elderly population? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 11(4):329–331

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL et al (2016) 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 37(29):2315–2381

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration (2019) Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet 393(10170):407–415

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM et al (2002) Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 360(9346):1623–1630

Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Ridker PM (2010) Rosuvastatin for primary prevention in older individuals with high C-reactive protein and low LDL levels: Exploratory analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 152(8):488-W174

Ridker PM, Lonn E, Paynter NP, Glynn R, Yusuf S (2017) Primary prevention with statin therapy in the elderly: New meta-analyses from the contemporary JUPITER and HOPE-3 Randomized Trials. Circulation 1

Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, Davis BR, Piller LB, Pervin H et al (2017) Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults. JAMA Intern Med 177(7):955–965

Giral P, Neumann A, Weill A, Coste J (2019) Cardiovascular effect of discontinuing statins for primary prevention at the age of 75 years: A nationwide population-based cohort study in France. Eur Heart J 40(43):3516–3525

Kim K, Lee CJ, Shim C-Y, Kim J-S, Kim B-K, Park S et al (2019) Statin and clinical outcomes of primary prevention in individuals aged >75 years: The SCOPE-75 study. Atherosclerosis 284:31–36

Jun JE, Cho I-J, Han K, Jeong I-K, Ahn KJ, Chung HY et al (2019) Statins for primary prevention in adults aged 75 years and older: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Atherosclerosis 283:28–34

Orkaby AR, Driver JA, Ho Y-L, Lu B, Costa L, Honerlaw J (2020) Association of statin use with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US veterans 75 years and older. JAMA 324(1):68

Lavie G, Hoshen M, Leibowitz M, Benis A, Akriv A, Balicer R, Reges O (2021) Statin therapy for primary prevention in the elderly and its association with new-onset diabetes, cardiovascular events, and all-cause mortality. Am J Med 134(5):643–652

Bezin J, Moore N, Mansiaux Y, Steg PG, Pariente A (2019) Real-life benefits of statins for cardiovascular prevention in elderly subjects: A population-based cohort study. Am J Med 132(6):740-748.e7

Ramos R, Comas-Cufí M, Martí-Lluch R, Balló E, Ponjoan A, Alves-Cabratosa L (2018) Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in old and very old adults with and without type 2 diabetes: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ k3359

Tobert JA, Newman CB (2016) The nocebo effect in the context of statin intolerance. J Clin Lipidol 10(4):739–747

Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B (2005) Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with highdosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients–the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 19:403–414

Howard JP, Wood FA, Finegold JA, Nowbar AN, Thompson DM, Arnold AD (2021) Side effect patterns in a crossover trial of statin, placebo, and no treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 78(12):1210–1222

Ott BR, Daiello LA, Dahabreh IJ, Springate BA, Bixby K, Murali M, Trikalinos TA (2015) Do statins impair cognition? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med 30(3):348–358

Nanna MG, Navar AM, Wang TY, Mi X, Virani SS, Louie MJ (2018) Statin use and adverse effects among adults >75 years of age: Insights from the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management (PALM) Registry. J Am Heart Assoc 7(10):e008546

Carlsson AC, Wändell P, Ösby U, Zarrinkoub R, Wettermark B, Ljunggren G (2013) High prevalence of diagnosis of diabetes, depression, anxiety, hypertension, asthma and COPD in the total population of Stockholm, Sweden - a challenge for public health. BMC Public Health 13:670

Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, Leimanis A, Otterblad Olausson P, Bergman U, Persson I, Sundström A, Westerholm B, Rosén M (2007) The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register–opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16(7):726–735

WHO collaborating Centre - ATC/DDD Index [Internet]. [cited 2023 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/?code=C10AA&showdescription=no

Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A (2009) The Swedish personal identity number: Possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 24(11):659–667

Wallach Kildemoes H, Vass M, Hendriksen C, Andersen M (2012) Statin utilization according to indication and age: A Danish cohort study on changing prescribing and purchasing behaviour. Health Policy 108(2–3):216–227

Ruscica M, Macchi C, Pavanello C, Corsini A, Sahebkar A, Sirtori CR (2018) Appropriateness of statin prescription in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med 50:33–40

Horodinschi R-N, Stanescu AMA, Bratu OG, Pantea Stoian A, Radavoi DG, Diaconu CC (2019) Treatment with statins in elderly patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 55(11):721

Gencer B, Marston NA, Im K, Cannon CP, Sever P, Keech A (2020) Efficacy and safety of lowering LDL cholesterol in older patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 396(10263):1637–1643

Ponce OJ, Larrea-Mantilla L, Hemmingsen B, Serrano V, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Spencer-Bonilla G (2019) Lipid-lowering agents in older individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104(5):1585–1594

Svilaas A, Strandberg T, Eriksson M, Hildebrandt P, Westheim A (2008) Lipid lowering treatment patterns and goal attainment in Nordic patients with hyperlipidemia. Scand Cardiovasc J Augusti 42(4):279–287

Johansen ME, Hefner JL, Foraker RE (2015) Antiplatelet and statin use in US patients with coronary artery disease categorized by race/ethnicity and gender, 2003 to 2012. Am J Cardiol 115(11):1507–1512

Nanna MG, Wang TY, Xiang Q, Goldberg AC, Robinson JG, Roger VL (2019) Sex differences in the use of statins in community practice. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 12(8):e005562

Driscoll A, Beauchamp A, Lyubomirsky G, Demos L, McNeil J, Tonkin A (2011) Suboptimal management of cardiovascular risk factors in coronary heart disease patients in primary care occurs particularly in women. Intern Med J 41(10):730–736

Maas AHEM, Appelman YEA (2010) Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J 18(12):598–602

Ofori-Asenso R, Jakhu A, Curtis AJ, Zomer E, Gambhir M, Korhonen MJ et al (2018) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the factors associated with nonadherence and discontinuation of statins among people aged ≥65 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 73:798–805

Odesjö H, Björck S, Franzén S, Hjerpe P, Manhem K, Rosengren A (2020) Adherence to lipid-lowering guidelines for secondary prevention and potential reduction in CVD events in Swedish primary care: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 10(10):e036920

Sheppard JP, Singh S, Fletcher K, McManus RJ, Mant J (2012) Impact of age and sex on primary preventive treatment for cardiovascular disease in the West Midlands, UK: Cross sectional study. BMJ 345:e4535

Forslund T, Carlsson AC, Ljunggren G, Ärnlöv J, Wachtler C (2021) Patterns of multimorbidity and pharmacotherapy: A total population cross-sectional study. Fam Pract 38(2):132–140

Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, Taylor DH, Ritchie CS, Bull JH, Fairclough DL (2015) Safety and benefit of discontinuing statin therapy in the setting of advanced, life-limiting illness: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 175(5):691–700

Singh S, Zieman S, Go AS, Fortmann SP, Wenger NK, Fleg JL (2018) Statins for primary prevention in older adults—moving toward evidence-based decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 66(11):2188–2196

Ju A, Hanson CS, Banks E, Korda R, Craig JC, Usherwood T, MacDonald P, Tong A (2018) Patient beliefs and attitudes to taking statins: Systematic review of qualitative studies. Br J Gen Pract 68(671):e408–e419

Ahmed ST, Akeroyd JM, Mahtta D, Street R, Slagle J, Navar AM, Stone NJ, Ballantyne CM, Petersen LA, Virani SS (2020) Shared decisions: A qualitative study on clinician and patient perspectives on statin therapy and statin-associated side effects. J Am Heart Assoc 9(22):e017915

Brown F, Singer A, Katz A, Konrad G (2017) Statin-prescribing trends for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Can Fam Physician 63(11):e495–e503

Upmeier E, Korhonen MJ, Helin-Salmivaara A, Huupponen R (2013) Statin use among older Finns stratified according to cardiovascular risk. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69(2):261–267

Region Stockholm Drug & Therapeutics Committee. Statins for cardiovascular prevention in high risk patients with ordinary and moderately elevated lipid levels. (In Swedish) Region Stockholm; 2020 [updated 2016; Available from: https://janusinfo.se/download/18.3daa1b3d160c00a26d21213d/1673854007426/Statiner-for-kardiovaskular-prevention-160504.pdf. Accessed 24 June 2024

Pettersson B, Hoffmann M, Wändell P, Levin LÅ (2012) Utilization and costs of lipid modifying therapies following health technology assessment for the new reimbursement scheme in Sweden. Health Policy 104(1):84–91

Davies EA, O’Mahony MS (2015) Adverse drug reactions in special populations - the elderly. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80(4):796–807

Rodriguez F, Maron DJ, Knowles JW, Virani SS, Lin S, Heidenreich PA (2017) Association between intensity of statin therapy and mortality in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol 2(1):47–54

Amarenco P, Kim JS, Labreuche J, Charles H, Abtan J, Béjot Y (2020) A Comparison of two LDL cholesterol targets after ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 382(1):9–19

Wallentin F, Wettermark B, Kahan T (2018) Drug treatment of hypertension in Sweden in relation to sex, age, and comorbidity. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 20(1):106–114

Wiréhn A-BE, Karlsson HM, Carstensen JM (2007) Estimating disease prevalence using a population-based administrative healthcare database. Scand J Public Health 35(4):424–431

Zarrinkoub R, Wettermark B, Wändell P, Mejhert M, Szulkin R, Ljunggren G (2013) The epidemiology of heart failure, based on data for 2.1 million inhabitants in Sweden. Eur J Heart Fail 15(9):995–1002

Halava H, Huupponen R, Pentti J, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J (2016) Predictors of first-year statin medication discontinuation: A cohort study. J Clin Lipidol 10(4):987–995

Mazhar F, Hjemdahl P, Clase CM, Johnell K, Jernberg T, Sjölander A, Carrero JJ (2022) Intensity of and adherence to lipid-lowering therapy as predictors of major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc 11(14):e025813

Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Olsen J (1996) A framework for evaluation of secondary data sources for epidemiological research. Int J Epidemiol 25(2):435–442

Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO (2011) External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11:450

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. The study was financed by local funds from Uppsala University and Region Stockholm.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BW and PH were responsible for the study conception and design. Data management, collection, and analysis were performed by CK and TF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by BW based on a prior master thesis written by CK, under the supervision of BW and PH. All authors commented on different versions of the manuscript as well as read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All patient data accessed by the researchers were fully pseudonymized. Consequently, it was not possible to identify individual patients or healthcare providers. Informed consent was not requested, in agreement with the Swedish legislation for conducting registry studies. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (registration numbers EPN 2015/579–31/2 and 2023–01601-02).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wettermark, B., Kalantaripour, C., Forslund, T. et al. Statin treatment for primary and secondary prevention in elderly patients—a cross-sectional study in Stockholm, Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-024-03724-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-024-03724-3