Abstract

Purpose

To describe prescribing of medicines in primary care in the last year of life in patients with dementia.

Method

A retrospective cohort analysis in UK primary care using routinely collected data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Number of medications and potentially inappropriate medication prescribed one year prior to, and including death, was ascertained.

Results

Dementia patients (n = 6923) aged 86.6 ± 7.3 years (mean ± SD) were prescribed 4.8 ± 4.0 drugs 1 year prior to death, increasing to 5.6 ± 4.0 2 months prior, before falling to 4.9 ± 4.1 at death. One year prior to death, 50% of patients were prescribed a potentially inappropriate medication, falling to 41% at death. Cardiovascular medications were the most common, with decreases in drug count only occurring in the last month prior to death. Prescriptions for gastrointestinal and central nervous system medication increased throughout the year, particularly laxatives/analgaesics, antidepressants and hypnotic/antipsychotics. Women (vs. men) and patients with Alzheimer’s (vs. vascular dementia) were prescribed 4.7% (95% CI 2.3%–7%) and 14.6% (11.7–17.3%) fewer medications, respectively. Prescribing decreased with age and increased with additional comorbidities.

Conclusions

Dementia patients are prescribed high levels of medication, many potentially inappropriate, during their last year of life, with reductions occurring relatively late. Improvements to medication optimisation guidelines are needed to inform decision-making around deprescribing of long-term medications in patients with limited life-expectancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Dementia is a growing challenge for primary health care services, with an estimated 7% of over 65 s affected [1], and numbers likely to increase given our ageing population. Polypharmacy, the co-prescription of multiple drugs, is common [2, 3] and a particular concern amongst patients with dementia. Memory loss and impaired cognitive function may lead to adherence problems with complex medication regimens, and patients may have difficulty in communicating problems related to adverse drug effects [4]. There is also evidence that inappropriate prescribing is frequent [5], and altered pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics may make the adverse consequences more serious in this older, multimorbid population.

These issues are especially concerning in the context of limited life expectancy, given the time required for demonstrable benefits to be achieved with certain medications [6, 7]. Furthermore, the evidence for clinical effectiveness of most drugs comes from randomised controlled trials which exclude individuals with dementia or at the end of life [8], so the balance of risks and benefits may be less favourable than in the general population. Current evidence of prescribing practices in dementia patients is predominantly from nursing home residents [9,10,11] or cross-sectional studies [12,13,14]. There has been limited study of changes in medication use during the last phases of life in patients with dementia in the community.

The aim of this study was to describe patterns of polypharmacy in the last year of life amongst adults with a diagnosis of dementia and examine variations in prescribing by demographic and clinical factors.

Method

Study population

We conducted a descriptive analysis using routinely collected, anonymised, UK primary care health records from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) [15]. Approval for the study was granted by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (Protocol reference 15_106R). The CPRD is a large database containing electronic medical health records of over 5 million active patients from approximately 650 general (family) practices (GP) and is considered a representative sample of the general UK population [15]. Coded data available for each patient include clinical diagnoses and detailed information on drugs prescribed [16, 17].

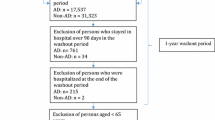

For this study, patients who had died between May 2013 and April 2014 and had a diagnosis of dementia at or before death were identified using the electronic GP medical records and linked Office of National Statistics death registry. A dementia diagnosis was defined using Read codes, a standard clinical coding classification used in UK primary care [18], for any relevant clinical diagnosis in the GP medical record or a relevant ICD-10 code in the death registry (Appendix 1).

Measurements

Polypharmacy was ascertained at death (i.e. an ongoing prescription on the date of death) and at 2 weeks, 1, 2, 4, 6, 9 and 12 months prior to death, from primary care records. These time intervals were based on pragmatism and clinical judgement. Almost all prescriptions issued by a GP to a patient will be captured by CPRD as prescribing is conducted almost exclusively electronically. Prescription length was calculated by dividing drug quantity by number of daily doses; where missing, imputed from the population average for that drug (Appendix 2). Drugs were categorised according to the British National Formulary (BNF) [19]. Palliative care medications were also identified (Appendix 3) [20]. Appropriateness of medications was classified using a previously published list developed using a Delphi consensus approach for adults with advanced dementia [7]. For this analysis, medications were defined as never appropriate and rarely appropriate (Appendix 3). In addition, prescribing safety indicators [21] taken from the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) indicator list [22] and used in the PINCER trial [23] and a general measure of potentially hazardous prescribing (≥ 1 of 19 indicators [P1–P19]) was derived for each time point. Prescriptions were limited to enteral-administered drugs, as the duration of individual prescriptions can be determined more reliably; these accounted for three-quarters of all medications in this population. For the analysis of palliative medications, we also included injectable drugs.

A count of all ongoing prescriptions of unique drug substances at each time point was derived. Counts were also derived for selected BNF chapters (most frequent enteral-administered prescriptions identified by Guthrie et al. [24]) and inappropriate medication. Throughout the paper, the term polypharmacy is used to indicate multiple concurrent medications, without implying appropriateness of medication or any particular minimum quantity.

A list of 37 physical and mental long-term conditions established by clinical expert consensus [25,26,27] was used to ascertain comorbidity status in participants at 1 year prior to death. An unweighted count of clinical conditions was derived, and a seven-category measure, grouping ≥ 6 conditions, was created.

Dementia subtype (vascular, Alzheimer’s disease, other and unspecified) and care home status during the last year of life were ascertained using clinical Read codes (Appendices 1 and 4, respectively). Analysis of dementia subtype was restricted to patients with a recorded diagnosis of vascular dementia or Alzheimer’s.

Statistical analysis

Counts and averages were used to describe changes in the number of prescriptions over time. Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression models were fitted to investigate differences in the number of prescriptions at each time point and across different demographic and clinical factors. Robust standard errors were used which allowed for correlations across different time points within individual patients (i.e. multiple prescription counts). A ZIP regression is a two-stage process, first predicting whether individuals had any prescriptions using a logit regression model, and secondly, a Poisson model to predict the rate of prescriptions amongst patients prescribed medication; the final output combining the two models. Number of days prior to death was included as a covariate in the logit and Poisson regression model, and univariable Poisson regression models were used to investigate associations with gender, age, dementia subtype, care home status and multimorbidity score. Estimates from the models are presented in terms of the expected relative difference (RD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) in number of medications prescribed per unit increase in the exposure of interest.

Interactions between each exposure and number of days until death were examined using a likelihood ratio test. For age and comorbidity, non-linear associations with prescription count were investigated and the most appropriate, as determined using likelihood ratio tests, is presented. Wald tests were used to test whether the association changed over time.

All analyses were conducted using Stata 14, and all statistical tests were two sided.

Results

A total of 6923 patients (mean age 86.6 ± 7.3 years, 64% female) with a diagnosis of dementia died during the study period (Table 1). Patients with vascular dementia had a mean of 4.0 ± 2.2 additional comorbidities, of which 1.9 ± 1.3 were cardiovascular disease (CVD) related, compared with 2.9 ± 2.0 comorbidities (1.1 ± 1.1 CVD related) for those with Alzheimer’s.

Of all products prescribed in the study period (n = 219,543), 69.2% (n = 151,975) were enteral administered. Remaining products included topical (11.9%, n = 26,019), non-pharmacological (5.6%, n = 12,208), injected (4.9%, n = 10,724), inhaled (2.1%, n = 4,532), administered to ears, eyes, or nose (1.9%, n = 4,133) and unknown (4.2%, n = 9,216).

Changes in overall prescribing over time

On average, dementia patients were prescribed 4.8 ± 4.0 enteral-administered drugs at baseline (1 year prior to death), increasing to 5.6 ± 4.1 1 month prior to death, falling to 4.9 ± 4.1 prescriptions ongoing on the date of death (Fig. 1). In the ZIP models, the overall number of drugs prescribed increased by 3.0% (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 4.5%) between the baseline and 1 month prior, with prescribing falling by 4.3% (− 5.9 to − 2.6%) at death compared with 1 year prior (Appendix 5).

Average (mean) number of prescriptions in the last year of life of dementia patients, stratified by appropriate prescribing All prescriptions restricted to enteral administered drugs. Never appropriate medication include lipid-lowering medication, cholinesterase inhibitors, antiplatelet agents (excluding aspirin), memantine, hormone antagonists, antioestrogen, leukotriene receptor antagonists, cytotoxic chemotherapy, sex hormones and immunomodulators. There were no prescriptions of antioestrogen, leukotriene receptor antagonists, cytotoxic chemotherapy, sex hormones and immunomodulators in the last year of life amongst the study population. Rarely appropriate medication includes bisphosphonates, warfarin, digoxin, bladder relaxants, tamsulosin, antiandrogens, alpha blockers, antiarrhythmics, antispasmodics, mineralocorticoids, clonidine, hydralazine and heparin. There were no prescriptions of clonidine, hydralazine and heparin in the last year of life amongst the study population

Palliative medication prescriptions (both enteral administered and injections) increased across the year, with a sharp rise from 0.5 ± 1.1 drugs 2 weeks prior to death to 1.2 ± 2.1 at death (Fig. 1), opioids being the most frequently prescribed. On the date of death, 41.0% (n = 2,838) of patients had at least one prescription for a palliative medication. In the ZIP model, the increase in palliative medication prescriptions at death represented nearly a 5-fold (474.3%; 418.0 to 538.4%) increase compared to 1 year prior.

Prescribing for specific therapeutic areas

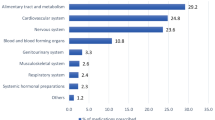

Stratified by BNF chapter, cardiovascular medications were the most frequently prescribed drugs throughout the last year of life, and musculoskeletal the least (Fig. 2a). On average, patients were prescribed 1.7 ± 2.0 cardiovascular drugs at baseline, with 1.3 ± 2.0 continuing to be prescribed at death, representing a 17.4% (− 15.1 to − 19.7%) fall (Fig. 2b). Levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium-channel blocker, beta-blockers and diuretics (ABCD medication) remained constant (≈0.8 drugs) until 1 month prior to death.

Average (mean) number of enteral prescriptions in the last year of life of dementia patients, stratified by BNF chapter. a Selected BNF chapters; b Indigestion BNF sub-chapter 1.1 & 1.3, laxatives BNF sub-chapter 1.6, other includes all remaining chapter 1 sub-chapters. c ABCD BNF sub-chapter 2.5.5.1/2, 2.4, 2.6.2 & 2.2.1-4/8, Anti-coagulants, anti-platelets BNF subchapter 2.8/9, Lipid-lowering BNF sub-chapter 2.12, other includes all remaining chapter 2 sub-chapters. d Antidepressants BNF sub-chapter 4.3, Analgesia BNF sub-chapter 4.7, Hypnotics and anti-psychotics BNF sub-chapter 4.1/2, Dementia medication BNF sub-chapter 4.11, other includes all remaining chapter 4 sub-chapters. BNF British National Formulary, ABCD angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, beta-adrenoceptor blocking drugs, calcium-channel blockers, Diuretics. All, never and rarely appropriate medication include enteral-administered drugs

There were increases in gastrointestinal medication and drugs affecting the central nervous system (CNS) over the 12 months prior to death. On average, prescriptions increased from 0.8 ± 1.0 to 0.9 ± 1.1 and 1.2 ± 1.5 to 1.5 ± 1.6 at 12 months and 1 month prior to death for gastrointestinal and CNS medication, respectively. After accounting for correlation over time, the number of gastrointestinal and CNS medication increased by 6.5% (1.7 to 11.6%) and 8.4% (5.1 to 11.9%), respectively, between 12 months and 1 month prior to death (Appendix 6). Increases were observed for laxatives and indigestion medication (Fig. 2c), and for analgaesics, antidepressants and hypnotics and antipsychotics (Fig. 2d).

Prescribing of inappropriate medications

One year prior to death, half (49.9%) of the patients were prescribed at least one drug considered inappropriate in severe dementia, dropping to 41.2% at death. Average number of inappropriate drugs fell from 1.0 ± 1.2 at 4 months to 0.7 ± 1.1 at death (Fig. 1). There was little change in prescribing of inappropriate medication until 1 month prior to death, when there was a 4.3% (− 0.6 to − 7.8%) decrease, with an even greater decrease of 11.2% (− 7.1 to − 15.1%) at death, compared with 1 year prior. Lipid-lowering agents and bisphosphates were the most commonly prescribed never and rarely appropriate medication, respectively (Fig. 3). Potentially hazardous prescribing followed a similar pattern, with over 16.4% of participants prescribed at least one 12 months prior to death, falling to 7.3% at death (Fig. 3a).

Proportion of dementia patients in the last year of life prescribed at least one inappropriate medication, and average (mean) number of prescriptions, stratified by appropriate prescribing. AP appropriate prescription, PHP potentially hazardous prescription. All prescriptions restricted to enteral administered drugs. Never appropriate medication include lipid-lowering medication, cholinesterase inhibitors, antiplatelet agents (excluding aspirin), memantine, hormone antagonists, antioestrogen, leukotriene receptor antagonists, cytotoxic chemotherapy, sex hormones and immunomodulators. There were no prescriptions of antioestrogen, leukotriene receptor antagonists, cytotoxic chemotherapy, sex hormones and immunomodulators in the last year of life amongst the study population. Rarely appropriate medication includes bisphosphonates, warfarin, digoxin, bladder relaxants, tamsulosin, antiandrogens, alpha blockers, antiarrhythmics, antispasmodics, ineralocorticoids, clonidine, hydralazine and heparin. There were no prescriptions of clonidine, hydralazine and heparin in the last year of life amongst the study population. Potentially hazardous prescribed is a composite measure of prescribing safety indicators P1-P19 [21]

Factors that influence differences in prescribing

The relative differences in prescribing between key demographic and clinical factors are presented in Fig. 4. Women, older patients and those with Alzheimer’s were generally prescribed fewer drugs overall compared with men (RD = − 4.7%; − 2.3 to − 7.0%), younger patients (oldest vs. youngest quartile, RD = − 15.6%; − 12.5 to − 18.5%) and those with vascular dementia (RD = − 14.6%; − 11.7 to − 17.3%). The magnitude of differences in overall prescribing between dementia subtypes decreased over time (Alzheimer’s vs. vascular − 16.0% (− 19.3 to − 12.5%) at 1 year; − 10.3% (− 14.2 to − 6.2%) at death; p = 0.002). Similar patterns were found for inappropriate prescribing (data not shown). There was no overall difference in prescribing between care home residency status, although inappropriate prescribing was lower in patients living in care homes compared with those not (RD = − 17.4%; − 12.3 to − 22.3%).

Average (mean) and relative difference (RD) in the number of enteral prescriptions in the last year of life of dementia patients by demographic and clinical factors. CI, confidence intervals. Zero-inflated Poisson regression models were fitted, and correlated standard errors at the patient level were used to account for the multiple measures (i.e. prescription counts) within individuals. Relative difference presented represents the average difference in drug count for a unit increase in the exposure over the year period. For age and multimorbidity, continuous measures were used. The reference for A. gender was men, and for C. dementia subtype was vascular dementia. *Evidence of statistical interaction between exposure and time from death (p value < 0.001). All medication includes enteral-administered drugs. A list of 37 physical and mental chronic conditions was used to ascertain multimorbidity status in participants 1 year prior to death. The condition list was based on work by Barnett et al. and clinical consensus [13, 14]

The number of drugs prescribed across the year varied by comorbidity status (p value < 0.001; Fig. 4d). Patients with a higher number of comorbidities experienced little change in the number of prescriptions in the last year of life, until near death when prescribing decreased. In contrast, prescribing increased amongst patients with fewer comorbidities.

Discussion

Findings from this study of electronic health records indicate that there are high levels of prescribing amongst dementia patients during their last year of life, with a significant proportion of the population prescribed an inappropriate medication throughout the year, with nearly half having such a prescription 2 weeks prior to death. The overall number of drugs increased over the last 12 months, and reductions were generally only observed relatively close to death. In particular, a high level of cardiovascular drugs was consistently prescribed until the final month, whilst gastrointestinal and CNS medication increased.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first general population study to investigate changes in the number and types of medication prescribed in primary care during the last year of life amongst patients who died with dementia. Combining primary care health records with national death registration data helped maximise identification of cases, providing a good representation of the UK population. Due to the ubiquitous nature of electronic prescribing in UK primary care, CPRD also provides full and detailed information on a patient’s prescribing history in primary care. Despite these strengths, several limitations are worth consideration, including potential misclassification and drug indication, which are common to most studies using these types of routine clinical data. Information on prescribing outside of primary care, including in secondary care and “over the counter” were not available. Detailed clinical information on dementia diagnosis and progression, such as age at diagnosis and severity, is not captured, as demonstrated by the high level of missing information on dementia subtype. Nevertheless, the underlying pathogenesis was still available in around two-thirds of cases. The definition of inappropriate medication was drawn from a list developed for advanced dementia, despite lack of information about severity. A recent large cohort study found that patients who died with a dementia diagnosis, only one-quarter were at the severe stage of the illness [28]; thus, the appropriateness of such a list may be limited. However, there is no agreed alternative definition of inappropriate prescribing for dementia patients in the end-of-life context, and our choice was thus a pragmatic one although nevertheless clinically relevant. We compared findings using an alternative, general measure of potentially hazardous prescribing, and found levels to be three times higher in our dementia study population than those observed in the older general population [21]. Similar conclusions from these two analyses highlights that there are important opportunities to potentially improve prescribing in this population. Finally, our cohort was defined by death, and it is therefore not possible to comment on how prescribing varies with prospective assessment of life expectation, either by clinical judgement (e.g. the “surprise question” [29]) or objective risk assessment (e.g. QMortality [30]). This would be an important direction for future work.

Comparison with existing literature

This study supports previous findings of high levels of prescribing amongst dementia patients and the ongoing use of inappropriate medication in this population. The number of medications prescribed was comparable with the existing literature (range, 4 to 5.4) [2, 5, 12, 31]. Consistent with previous longitudinal studies [9,10,11, 32], our results indicate that dementia patients experience an overall increase in prescribing in the last year of life. Levels of inappropriate prescribing were similar to those reported elsewhere. A US study of nursing home residents with advanced dementia found half were prescribed at least 1 drug with questionable benefit [33]. Based on the RCGP safety indicators, hazardous prescribing appears to have declined over the 12 months reflecting implementation of appropriate improvements in prescription regimen, although rates were still considerably higher than the general population [21]. Furthermore, inappropriate prescribing quantified by specific therapeutic classes persisted until relatively late in life.

As indicated elsewhere [34], older patients had lower levels of prescribing compared with younger patients, suggesting physicians may be considering limited life expectancy and withholding treatments in the older age groups. Women were prescribed fewer drugs overall, with fewer high-risk medications compared with men. This may, in part, be accounted for by women being older and having fewer comorbidities. In the literature, there are mixed results relating to gender differences in prescribing, in particular with relation to inappropriate medication [9, 31]; this probably reflects variations in dementia severity and definitions of inappropriate prescribing between studies.

As in the general population, we found comorbidity to be associated with higher levels of prescribing [5, 12, 13, 35]. Dementia patients with higher levels of comorbidity experienced little change in their medication in their last year of life, whilst those with fewer comorbidities were prescribed more medications. This difference reflects low levels of medication at baseline amongst patients with no other conditions, with increases probably indicating health deterioration and prescribing related to symptom management.

Implications for research and/or practice

Findings from this study indicate that dementia patients receive considerable numbers of medications in their last year of life, many of which are considered inappropriate. Although rates of potentially hazardous prescribing did decline somewhat, these observations nevertheless support the need for improved medication optimisation strategies for patients experiencing polypharmacy [36]. Furthermore, they demonstrate that, outside of the palliative care setting, withdrawal or reduction of medications is uncommon. In part, this reflects the difficulties of predicting death 12 months in advance; clinicians may be reluctant to reduce potentially life-prolonging treatment in the face of considerable uncertainty around life expectancy, and indeed may not consider deprescribing in the first place if the patient is not obviously dying. The findings may also reflect the lack of a strong evidence base or any clinical guidelines to inform decisions around deprescribing of long-term medications [37].

Clinicians and policy makers alike need to ensure that medication optimisation remains a prominent aspect of clinical management for patients with dementia towards the end of life. There is also a pressing need to develop better evidence to support improved prescribing for these patients. This should include enhanced trial data for the effectiveness of long-term medications, improved methods for the identification of individuals with limited life expectancy and better medication optimisation strategies tailored to the specific needs of this vulnerable population.

Abbreviations

- CPRD:

-

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

- GP:

-

General practice

- BNF:

-

British National Formulary

- ZIP:

-

Zero-inflated Poisson

References

Prince M, Knapp M, Guerchet M, McCrone P, Prina M, Comas-Herrera A, Wittenberg R, Adelaja B, Hu B, King D, Rehill A, Salimkumar D (2014) Dementia UK: update. Second edition. Alzheimer’s Society, London

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Harris AT, Trittschuh E, Shega J, Weintraub S (2010) Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among community-dwelling elders with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 24(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819d6ec9

Lalic S, Sluggett JK, Ilomaki J, Wimmer BC, Tan EC, Robson L, Emery T, Bell JS (2016) Polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity as risk factors for hospitalization among residents of long-term care facilities: a prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 17(11):1067 e1061–1067 e1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.08.019

Onder G, Lattanzio F, Battaglia M, Cerullo F, Sportiello R, Bernabei R, Landi F (2011) The risk of adverse drug reactions in older patients: beyond drug metabolism. Curr Drug Metab 12(7):647–651

Andersen F, Viitanen M, Halvorsen DS, Straume B, Engstad TA (2011) Co-morbidity and drug treatment in Alzheimer’s disease. A cross sectional study of participants in the dementia study in northern Norway. BMC Geriatr 11:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-58

Onder G, Liperoti R, Foebel A, Fialova D, Topinkova E, van der Roest HG, Gindin J, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Fini M, Gambassi G, Bernabei R, project S (2013) Polypharmacy and mortality among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14(6):450 e457–450 e412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.014

Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Shega JW, Hougham GW, Cox Hayley D, Dale W (2008) Integrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc 56(7):1306–1311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01741.x

Stevenson J, Abernethy AP, Miller C, Currow DC (2004) Managing comorbidities in patients at the end of life. BMJ 329(7471):909–912. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7471.909

Tjia J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Mitchell SL (2010) Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(5):880–888. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02819.x

Blass DM, Black BS, Phillips H, Finucane T, Baker A, Loreck D, Rabins PV (2008) Medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23(5):490–496. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1921

Jansen K, Schaufel MA, Ruths S (2014) Drug treatment at the end of life: an epidemiologic study in nursing homes. Scand J Prim Health Care 32(4):187–192. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2014.972068

Clague F, Mercer SW, McLean G, Reynish E, Guthrie B (2017) Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Age Ageing 46(1):33–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw176

Browne J, Edwards DA, Rhodes KM, Brimicombe DJ, Payne RA (2017) Association of comorbidity and health service usage among patients with dementia in the UK: a population-based study. BMJ Open 7(3):e012546. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012546

Colloca G, Tosato M, Vetrano DL, Topinkova E, Fialova D, Gindin J, van der Roest HG, Landi F, Liperoti R, Bernabei R, Onder G, project S (2012) Inappropriate drugs in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment: results from the shelter study. PLoS One 7(10):e46669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046669

Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, Forbes H, Mathur R, van Staa T, Smeeth L (2015) Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 44(3):827–836. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv098

Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ (2010) Validation and validity of diagnoses in the general practice research database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 69(1):4–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03537.x

Williams T, Van Staa T, Puri S, Eaton S (2012) Recent advances in the utility and use of the general practice research database as an example of a UK primary care data resource. Ther Adv Drug Saf 3:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098611435911

Booth N (1994) What are the Read Codes? Health Libr Rev 11(3):177–182

Committee JF (2015) British national formulary. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, London

Payne R, Denholm R (2018) CPRD product code lists used to define long-term preventative, high-risk, and palliative medication. University of Bristol. https://doi.org/10.5523/bris.k38ghxkcub622603i5wq6bwag

Stocks SJ, Kontopantelis E, Akbarov A, Rodgers S, Avery AJ, Ashcroft DM (2015) Examining variations in prescribing safety in UK general practice: cross sectional study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ 351:h5501. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5501

Spencer R, Bell B, Avery AJ, Gookey G, Campbell SM, Royal College of General P (2014) Identification of an updated set of prescribing--safety indicators for GPs. Brit J Gen Pract 64(621):e181–e190. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X677806

Avery AJ, Rodgers S, Cantrill JA, Armstrong S, Cresswell K, Eden M, Elliott RA, Howard R, Kendrick D, Morris CJ, Prescott RJ, Swanwick G, Franklin M, Putman K, Boyd M, Sheikh A (2012) A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised, controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet 379(9823):1310–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61817-5

Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T (2015) The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug-drug interactions: population database analysis 1995-2010. BMC Med 13:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0322-7

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B (2012) Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 380(9836):37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2

University of Cambridge PCU (2017) Co-morbidity taxonomy code lists. Version 1.0 Lists. http://www.phpc.cam.ac.uk/pcu/cprd_cam/codelists/

Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, Rhodes K, Brimicombe J, Payne R, Griffin S (2018) The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Brit J Gen Pract 68(669):e245–e251. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X695465

Aworinde J, Werbeloff N, Lewis G, Livingston G, Sommerlad A (2018) Dementia severity at death: a register-based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1930-5

White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P (2017) How accurate is the 'Surprise Question' at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0907-4

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C (2017) Development and validation of QMortality risk prediction algorithm to estimate short term risk of death and assess frailty: cohort study. BMJ 358:j4208. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4208

Oesterhus R, Aarsland D, Soennesyn H, Rongve A, Selbaek G, Kjosavik SR (2017) Potentially inappropriate medications and drug-drug interactions in home-dwelling people with mild dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 32(2):183–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4456

Maddison AR, Fisher J, Johnston G (2011) Preventive medication use among persons with limited life expectancy. Prog Palliat Care 19(1):15–21. https://doi.org/10.1179/174329111X576698

Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Peterson D, Liu Q, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL (2014) Use of medications of questionable benefit in advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med 174(11):1763–1771. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4103

Lu WH, Wen YW, Chen LK, Hsiao FY (2015) Effect of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications and anticholinergic burden on clinical outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 187(4):E130–E137. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141219

Payne RA, Abel GA, Avery AJ, Mercer SW, Roland MO (2014) Is polypharmacy always hazardous? A retrospective cohort analysis using linked electronic health records from primary and secondary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol 77(6):1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12292

Duerden M, Avery AJ, Payne RA (2013) Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation. Making it safe and sound. The Kings Fund, London

Parsons C, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Lapane KL (2010) Withholding, discontinuing and withdrawing medications in dementia patients at the end of life: a neglected problem in the disadvantaged dying? Drugs Aging 27(6):435–449. https://doi.org/10.2165/11536760-000000000-00000

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Adrian Root for his method in imputing missing prescription information.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Approval for the study was granted by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (Protocol reference 15_106R).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 227 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Denholm, R., Morris, R. & Payne, R. Polypharmacy patterns in the last year of life in patients with dementia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 1583–1591 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02721-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02721-1