Abstract

Purpose

STOPPFrail criteria highlight instances of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) in frailer older adults with poor 1-year survival prognosis. The objectives of this study were to (i) determine the proportion of older adults requiring long-term nursing care in whom STOPPFrail criteria are applicable, (ii) measure the prevalence of STOPPFrail PIMs, and (iii) identify risk factors for PIMs in this cohort.

Methods

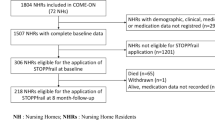

We retrospectively reviewed applications for long-term nursing care to nursing homes in the Cork area over a 6-month period. We recorded diagnoses, medications, functional status, cognitive ability, frailty status, and applied STOPPFrail criteria as appropriate.

Results

We reviewed 464 applications; 38 were excluded due to incomplete information and 274 patients (64.3%) met STOPPFrail eligibility criteria (median age 83 years (IQR 77.25–88); 233 (54.7%) female). Those STOPPFrail eligible were prescribed 2194 medications (mean 8, (SD 4)), of which 828 (37.7%) were PIMs. At least one PIM was identified in 250 eligible patients (91.2%). The median number of PIMs was 3 (IQR 2–4), the most common being (i) medications without clear indication identified in 47.0% (n = 129) of patients, (ii) long-term high-dose proton pump inhibitors in 31.4% (n = 86), and (iii) statins in 29.6% (n = 81). For every additional medication prescribed, the odds of identifying a PIM increased by 58% (odds ratio 1.58, 95% CI 1.32–1.89, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Almost 65% of patients awaiting long-term care are eligible for the application of STOPPFrail criteria with over 90% prescribed at least one PIM. Transition to nursing home care represents an opportunity to review therapeutic appropriateness and goals of prescribed medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kojima G (2015) Prevalence of frailty in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16(11):940–945

Moore KL, Boscardin WJ, Steinman MA, Schwartz JB (2014) Patterns of chronic co-morbid medical conditions in older residents of U.S. nursing homes: differences between the sexes and across the age span. J Nutr Health Aging 18(4):429–436

Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D et al (2012) Polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the SHELTER study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67(6):698–704

Kelly A, Conell-Price J, Covinsky K, Cenzer IS, Chang A, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK (2010) Length of stay for older adults residing in nursing homes at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(9):1701–1706

Heppenstall CP, Broad JB, Boyd M, Hikaka J, Zhang X, Kennedy J, Connolly MJ (2016) Medication use and potentially inappropriate medications in those with limited prognosis living in residential aged care. Australas J Ageing 35(2):E18–E24

Tosato M, Landi F, Martone AM, Cherubini A, Corsonello A, Volpato S, Bernabei R, onder G, on behalf of Investigators of the CRIME Study (2014) Potentially inappropriate drug use among hospitalised older adults: results from the CRIME study. Age Ageing 43(6):767–773

Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I, Pearson SA, Lindsey L, Holmes H (2017) Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 7(2):113–121

Ailabouni NJ, Nishtala PS, Mangin D, Tordoff JM (2016) Challenges and enablers of deprescribing: a general practitioner perspective. PLoS One 11(4):e0151066

Palagyi A, Keay L, Harper J, Potter J, Lindley RI (2016) Barricades and brickwalls – a qualitative study exploring perceptions of medication use and deprescribing in long-term care. BMC Geriatr 16(1):1–11

Harriman K, Howard L, McCracken R (2014) Deprescribing medication for frail elderly patients in nursing homes: a survey of Vancouver family physicians. B C Med J 56(9)

Schuling J, Gebben H, Veehof LJG, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM (2012) Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multimorbidity: the view of Dutch GPs. A qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract 13:56

Lavan AH, Gallagher P, Parsons C, O'Mahony D (2017) STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy): consensus validation. Age Ageing 46(4):600–607

Lavan AH, Gallagher P, O'Mahony D (2017) Inter-rater reliability of STOPPFrail [Screening Tool of Older Persons Prescriptions in Frail adults with limited life expectancy] criteria amongst 12 physicians. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 74(3):331–338

The Deparment of Health, Healthy Ireland and the National Patient Safety Office. Review of the Nursing Homes Support Scheme, A Fair Deal

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965) Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Maryland state medical journal 14:61–65

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12(3):189–198

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 173(5):489–495

Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, Ariail JC, Simpson KN (2008) Polypharmacy: misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging 3(2):383–389

Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel LEE (1968) Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 16(5):622–626

O’Sullivan D, O’Mahony D, Parsons C et al (2013) A prevalence study of potentially inappropriate prescribing in Irish long-term care residents. Drugs Aging 30:39–49

Ryan C, O’Mahony D, Kennedy J et al (2013) Potentially inappropriate prescribing in older residents in Irish nursing homes. Age Ageing 42:116–120

Narayan SW, Nishtala PS (2018) Population-based study examining the utilization of preventive medicines by older people in the last year of life. Geriatr Gerontol Int 18(6):892–898

Feng Z, Hirdes JP, Smith TF, Finne-Soveri H, Chi I, du Pasquier JN, Gilgen R, Ikegami N, Mor V (2009) Use of physical restraints and antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(10):1110–1118

Foevel AD, Liperoti R, Onder G et al (2014) Use of antipsychotic drugs among residents with dementia in European long-term care facilities: results from the SHELTER study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(12):911–917

Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T, Peterson D, Gurwitz JH (2013) Antipsychotic use among nursing home residents. JAMA 309(5):440–442

Kamble P, Chen H, Sherer J, Aparasu RR (2008) Antipsychotic drug use among elderly nursing home residents in the United States. Am J Geriatri Pharmacother 6(4):187–197

Curtine D, Dukelow T, James K et al (2018) Deprescribing in multi-morbid older people with polypharmacy: agreement between STOPPFrail explicit criteria and gold standard deprescribing using 100 standardized clinical cases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol

Gallagher P, O’Connor M, O’Mahony D (2011) Prevention of potentially inappropriate prescribing for elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial using STOPP/SART criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther 89(6):845–854

Dalleur O, Boland B, Losseau C, Henrard S, Wouters D, Speybroeck N, Degryse JM, Spinewine A (2014) Reduction of potentially inappropriate medication use using the STOPP criteria in frail older inpatients: a randomised controlled study. Drugs Aging 31(4):291–298

O’Connor MN, O’Sullivan D, Gallagher PF et al (2016) Prevention of hospital-acquired adverse drug reactions in older people using screening tool of older persons’ prescriptions and screening tool to alert to right treatment criteria: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(8):1558–1566

National Institue on Ageing and National Institutes of Health (2011) World Health Organisation: Global Health and Ageing

Salive ME (2013) Multimorbidity in older adults. Epidemiol Rev 35:75–83

Moore N, Lecointre D, Noblet C, Mabille M (1998) Frequency and cost of serious adverse drug reactions in a department of general medicine. Br J Clin Pharmacol 45(3):301–308

Leendertse AJ, Van Den Bemt PM, Poolman JB, Stoker LJ, Egberts AC, Postma MJ (2011) Preventable hospital admissions related to medication (HARM): cost analysis of the HARM study. Value Health 14(1):34–40

Barry M, Usher C, Tilson L (2010) Public drug expenditure in the Republic of Ireland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 10(3):239–245

Executive Agency for Health and Consumers – EAHC – European Commission (2012) EU Pharmaceutical expenditure forecast

Aitken M, Berndt ER, Cutler DM (2009) Prescription drug spending trends in the United States: looking beyond the turning point. Health Aff 28(1):w151–w160

Funding

This research has been funded as part of the SENATOR project funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (EU FP7) programme (grant number 305930). Health Research Board Clinical Research Facility at University College Cork (HRB CRF-C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The local Clinical Research Ethics Committee at University College Cork (UCC) approved the study protocol.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lavan, A.H., O’Mahony, D. & Gallagher, P. STOPPFrail (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions in Frail adults with a limited life expectancy) criteria: application to a representative population awaiting long-term nursing care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 723–731 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02630-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02630-3