Abstract

Purpose

Nitisinone inhibits the cytochrome P450 (CYP) subfamilies CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1 and the organic anion transporter (OAT) isoforms OAT1 and OAT3 in vitro. Since the effect of nitisinone on these enzymes and transporters in humans is still unknown, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of nitisinone on these CYP subfamilies and OAT isoforms.

Methods

This was an open-label, nonrandomized, two-arm, phase 1 study (EudraCT: 2016-004297-17) in healthy volunteers. The substrates (tolbutamide, metoprolol, and chlorzoxazone for the respective CYPs and furosemide for the OATs) were administered as single doses, before and after 15 days of once daily dosing of 80 mg nitisinone, to determine the AUC∞ ratios ([substrate+nitisinone]/[substrate]). Nitisinone pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability were also assessed, and blood and urine were collected to determine substrate and nitisinone concentrations by LC-MS/MS.

Results

Thirty-six subjects were enrolled with 18 subjects included in each arm. The least square mean ratio (90% confidence interval) for AUC∞ was 2.31 (2.11–2.53) for tolbutamide, 0.95 (0.88–1.03) for metoprolol, 0.73 (0.67–0.80) for chlorzoxazone, and 1.72 (1.63–1.81) for furosemide. Clinically relevant nitisinone steady-state concentrations were reached after 12 days: mean Cav,ss of 94.08 μM. All treatments were well tolerated, and no safety concerns were identified.

Conclusions

Nitisinone did not affect CYP2D6 activity, was a weak inducer of CYP2E1, and was a weak inhibitor of OAT1 and OAT3. Nitisinone was a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9, and treatment may therefore result in increased plasma concentrations of comedications metabolized primarily via this enzyme.

Clinical trial registry identification

EudraCT 2016-004297-17.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nitisinone (2-(2-nitro-4-trifluormethyl-benzyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione, also known as NTBC) in combination with strict dietary restrictions is the first-line treatment for patients with the rare autosomal recessive disorder hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (HT-1; OMIM reference 276700) [1]. Before the introduction of nitisinone, most patients did not survive their 10th birthday unless they underwent liver transplantation [2]. Today, this group of patients is reaching adulthood and with the increasing age, comedications with other drugs can be expected to increase.

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of nitisinone have been evaluated both in healthy volunteers and patients. The median terminal half-life in plasma was estimated to 54 h (range 39 to 86 h) after a single dose of 1 mg/kg nitisinone in ten healthy volunteers [3]. The apparent clearance was estimated to 0.0956 L/kg body weight/day (corresponding to 4.0 mL/h/kg) and the half-life to 52 h in a population PK analysis on a group of 207 patients with HT-1 [4]. Finally, in 32 patients with alkaptonuria, the apparent clearance of nitisinone was estimated to 3.18 mL/h/kg [5]. In vitro data show that nitisinone itself is metabolized by CYP3A4 and dose adjustments may therefore be needed if it is coadministered with drugs modulating the activity of this enzyme [4].

One in vitro study using pooled human liver microsomes indicated that nitisinone is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9 (IC50 = 46 μM) and a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2E1 (IC50 > 100 μM). No inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19, or CYP3A4 activity was observed (Sobi unpublished data). Another study showed that nitisinone is a direct inhibitor of human CYP2C9 with an IC50 of 11 μM, whereas nitisinone caused no inhibition of CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C19, 2D6, or 3A4/5 [6]. Taken together, potential inhibition of CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1 could not be excluded, whereas nitisinone was not expected to inhibit CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C8, 2C19, or 3A4/5. An in vitro study on transporter proteins showed that nitisinone is not an inhibitor or substrate of permeability glycoprotein (P-gp) in Caco-2 cells, furthermore that nitisinone is not an inhibitor of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) based on bidirectional permeability of prazosin across MDCKII-BCRP cells and finally that nitisinone does not inhibit OATP1B1, OATP1B3 and OCT2, whereas inhibition of OAT1 (IC50 = 6.87 μM) and OAT3 (IC50 = 3.11 μM) could not be excluded based on transporter-expressing cells (Sobi unpublished data).

In this clinical study, we investigated the effect of nitisinone on the AUC of model substrates for CYP2D6, CYP2E1, CYP2C9, and OAT1/OAT3 in healthy volunteers, in order to estimate the degree of inhibition expected when nitisinone is coadministered with drugs mainly eliminated by these enzymes or transporters. The steady-state PK of nitisinone was also characterized.

Subjects and methodology

Study design

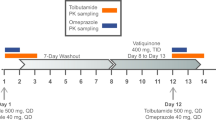

This was an open-label, non-randomized, two-arm, phase 1 study with the primary objective to evaluate the potential inhibition of nitisinone on the CYP isoenzymes, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1, and on the organic anion transporters, OAT1 and OAT3. The study aimed to enroll 18 subjects in each of two treatment arms. In arm A, the effect of nitisinone on the CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1 activities was investigated using the model substrates tolbutamide, metoprolol, and chlorzoxazone, respectively [1, 7]. In arm B, the combined effect of nitisinone on OAT1 and OAT3 was investigated by the model substrate furosemide (Fig. 1) [8]. The primary endpoint was AUC∞ for these substrates before and after coadministration of nitisinone, which was supported by the secondary endpoints Cmax, tmax, AUClast, and t½,z. Secondary objectives were to evaluate the steady-state PK of nitisinone and to evaluate the safety and tolerability of multiple dosing of nitisinone by assessing AEs and safety laboratory variables.

Study design. This was an open-label, nonrandomized study in healthy volunteers investigating the potential inhibitory effect of nitisinone on the CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1 enzymes (arm A), and the renal transporters OAT1/OAT3 (arm B). Subjects in arm A received a single dose of CYP substrates (tolbutamide, chlorzoxazone, metoprolol) followed by a 48-h PK assessment period. This was followed by administration of nitisinone (80 mg once daily for 16 days). After 14 days, a second dose of CYP substrates was administered, followed by a 48-h PK assessment period. Subjects in arm B received an OAT1/OAT3 substrate (intravenous furosemide) with a similar setup and assessment as in arm A as indicated

Subjects

Subjects eligible for study participation were healthy male and female volunteers, 18 to 55 years of age. Pregnancies were not allowed and women of childbearing potential had to follow nonhormonal contraceptive methods and have a negative pregnancy test at the time of screening. Additional inclusion criteria were as follows: body weight of 64 to 100 kg, BMI of 18 to 30 kg/m2, and a signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria included, but were not limited to, poor or ultra-rapid metabolism of CYP2D6 substrates confirmed by genotyping (for arm A), recent history or presence of clinically significant gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, cardiovascular, hematological, metabolic, urological, pulmonary, neurological or psychiatric disorders, daily smoking of > 10 cigarettes, daily consumption of > 5 cups of coffee, history of drug, and/or alcohol abuse.

The study was conducted during March through July 2017, according to ICH GCP guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by an independent ethical committee (Geschäftsstelle der Ethik-Kommission des Landes Berlin, Berlin, Germany).

Interventions

Subjects were admitted to the clinic before the first administration of the substrates (day − 1) and remained in the clinic during the PK sampling period. Following discharge, all subjects received 80 mg nitisinone once daily as four 20-mg capsules (Sobi, Sweden) for 16 days in arm A or 15 days in arm B. The dose of nitisinone aimed at achieving plasma levels at least as high as those recommended in the treatment of HT-1 [1], and the duration of dosing was sufficient to reach and maintain steady state during the PK sampling period for the substrates.

In arm A, subjects were administered a single dose of CYP substrates (metoprolol 50 mg, 1 tablet [Ratiopharm, Germany], tolbutamide 500 mg, 1 tablet [Actavis, UK], and chlorzoxazone 250 mg, 1 capsule [BioPhausia, Sweden]), 2 days before nitisinone administration and on day 15 of nitisinone administration. Tolbutamide was administered within 30 min after breakfast, and metoprolol and chlorzoxazone were administered 1 h after tolbutamide dosing. The use of this combination of CYP substrates has been evaluated previously [9].

In arm B, a 15-min 20-mg intravenous infusion of furosemide was given 3 to 3.5 h after breakfast (10 mg/mL, furosemide [Ratiopharm, Germany]) 1 day before nitisinone administration and on day 15 of nitisinone administration.

Sample collection

In arm A, blood samples were collected predose and at 11 predefined time points up to 48 h after intake of tolbutamide for determination of tolbutamide in plasma, at 11 predefined time points up to 12 h after intake of tolbutamide for determination of metoprolol in plasma, and finally at 13 predefined time points up to 24 h after the intake of tolbutamide for determination of chlorzoxazone in plasma. Blood samples for determination of nitisinone in plasma were collected predose on days 1, 2, 6, 12, 13, 14, and thereafter at 14 preplanned time points up to 24 h after administration of nitisinone on day 14 of dosing. Urine for determination of nitisinone was collected in 3- and 12-h intervals on day 14.

In arm B, blood samples for determination of furosemide in plasma were collected predose and at 12 preplanned time points up to 8 h after administration and for determination of nitisinone in plasma predose on days 1, 2, 6, 12, 13, and 14 of dosing.

Bioanalytical methods

Quantitative analyses of tolbutamide, metoprolol, chlorzoxazone, and furosemide in plasma and nitisinone in plasma and urine were performed at the Parexel Bioanalytical Services Division in Bloemfontein, South Africa, using validated LC-MS/MS methods. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) were as follows: tolbutamide in plasma 0.107 μg/mL, metoprolol in plasma 2.00 ng/mL, chlorzoxazone in plasma 0.0195 μg/mL, furosemide in plasma 10.00 ng/mL, nitisinone in plasma 1.18 μmol/L, and nitisinone in urine 1.95 μmol/L. A detailed description of the bioanalytical methods is provided as supplementary information.

Pharmacogenetic analysis

Individuals with poor and ultra-rapid CYP2D6 metabolism, with an overall CYP2D6 functional allele activity of < 0.5 or > 2.5 were excluded from this study based on a composite functionality score of the genotype (*3, *4, *5, *6, *10, *17, *41, *2XN) and the corresponding allele functionality on each single chromosome [10].

Pharmacokinetic evaluation

Plasma PK parameters were calculated by noncompartmental analysis in Phoenix WinNonlin Version 6.3, using Model 200 (extravascular administration) and Model 202 (constant infusion), based on individual plasma concentration data and the exact individual sampling time points. Concentrations below the LLOQ at early time points (lag-time) were treated as zero, and LLOQ appearing in the terminal samples were omitted from the analysis. PK parameters included maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax), time of Cmax (tmax), terminal half-life (t½,z), area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time 0 to last sample (AUClast) calculated with the linear-log trapezoidal method, and AUC up to infinity (AUC∞).

For nitisinone, the minimal, maximal, and average plasma concentration within a dosing interval (Cmin,ss, Cmax,ss, and Cav,ss) were derived as well as apparent clearance (CL/F). Renal clearance (CLR) was calculated as the amount of nitisinone excreted in the urine (day 14 of dosing) (Ae) divided by AUC within the same dosing interval at steady state, and the fraction excreted as unchanged nitisinone in the urine (fe) was calculated as Ae/dose.

Inhibition of CYP isoenzymes or OAT1/OAT3 transporters was defined according to guidelines for drug interaction studies by an AUC ratio exceeding unity as follows: weak inhibition was defined as a ratio ≥ 1.25 and < 2.0, moderate inhibition as a ratio ≥ 2.0 and < 5.0, and finally strong inhibition as a ratio ≥ 5.0 [7, 11].

Sample size

The number of subjects in arm A was selected to ensure appropriate power for statistical analysis of the metoprolol data, as this substance has the largest intraindividual variability among the CYP substrates in this study [12, 13]. Allowing for a CV of 25% for AUC∞, a sample size of 18 gives a power of more than 90% to conclude that there is at most a weak inhibition at the 0.05 significance level, given boundaries for weak inhibition of 0.5 and 2.0 [7, 11], and assuming that the magnitude of inhibition corresponds to a true AUC ratio of 1.5. A similar intraindividual variability was assumed for intravenous infusion of furosemide, and 18 subjects were included also in arm B.

Statistics

Continuous variables were analyzed per treatment group and time point using descriptive statistics. For relevant PK variables, the geometric mean, CV, and geometrical coefficient of variation were also calculated. For each substrate, the following linear mixed model was fitted: log AUCij = m + Sj + tiT + εij where Sj is the subject-specific normal random effect for subject j, ti is zero when i = 1 (substrate alone) and one when i = 2 (substrate + nitisinone), T was the added effect when nitisinone was given in addition to the substrate, and εij was the normal residual error. Model-based point estimates and confidence intervals (CIs) for T were calculated and exponentiated in order to derive a 90% CI for the estimated AUC∞ ratio.

Results

Disposition of subjects

In total, 36 healthy volunteers were enrolled in the study, 18 in each arm. All subjects completed the study according to the protocol and were included in the PK analysis. The overall mean (SD) age was 39.7 (10.8) years, all subjects were white, the majority were men (72.2%), and the overall BMI was within normal range; the mean (SD) was 24.81 (2.65) (Supplementary Table 1).

Effect of nitisinone on CYP and OAT substrates

Tolbutamide plasma concentrations were higher when administered with nitisinone than when administered alone (Fig. 2a). The median tmax for tolbutamide was similar in the presence or absence of nitisinone, while the geometric mean Cmax was slightly higher in the presence of nitisinone, and the t½,z was longer in the presence of nitisinone (17.2 vs. 7.9 h). Consequently, the AUC∞ for tolbutamide was larger in the presence of nitisinone (Supplementary Table 2), and the LS mean (90% CI) AUC∞ ratio was 2.31 (2.11–2.53), indicating that nitisinone is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9 (Table 1).

Plasma concentrations of tolbutamide (CYP2C9 substrate), metoprolol (CYP2D6 substrate), chlorzoxazone (CYP2E1 substrate), and furosemide (OAT1/OAT3 substrate) in the presence or absence of nitisinone. The geometric mean (± SD) plasma concentration-time profiles are plotted for a tolbutamide, b metoprolol, c chlorzoxazone, and d furosemide

Metoprolol PK parameters were similar in the presence or absence of nitisinone and the LS mean (90% CI) AUC∞ ratio was 0.95 (0.88–1.03), indicating that nitisinone does not affect CYP2D6 (Table 1; Supplementary Table 2; Fig. 2b).

Chlorzoxazone plasma concentrations were lower when administered with nitisinone than when administered alone (Fig. 2c). The median tmax occurred slightly later, the geometric mean Cmax was slightly lower in the presence of nitisinone, whereas the geometric mean t½,z for chlorzoxazone was similar in the presence or absence of nitisinone (Supplementary Table 2), which resulted in a lower geometric mean AUC∞ for chlorzoxazone in the presence of nitisinone. The LS mean (90% CI) AUC∞ ratio was 0.73 (0.67–0.80), indicating that nitisinone is a weak inducer of CYP2E1 (Table 1).

Furosemide plasma exposure was higher when administered with nitisinone than when administered alone (Fig. 2d). The median tmax was similar in the presence or absence of nitisinone, whereas the geometric mean Cmax was slightly higher; the geometric mean t½,z was slightly longer and the geometric mean AUC∞ was larger in the presence of nitisinone (Supplementary Table 2). The LS mean (90% CI) AUC∞ ratio was 1.72 [1.63–1.81], indicating that nitisinone is a weak inhibitor of OAT1 and OAT3 (Table 1).

Nitisinone plasma and urine PK

Nitisinone plasma concentrations remained relatively constant over the 24-h PK assessment period following 14 days of 80 mg nitisinone once-daily dosing in arm A. Predose concentrations were comparable in both arms and confirmed that steady state was reached by the 12th day of dosing. The geometric mean Cav,ss was 92.87 μM, the CL/F was 111.7 mL/h, and the t½τ,ss was 40.77 h (Table 2).

Nitisinone urine concentrations were low and quantifiable in only 3 out of 18 subjects. In these subjects, fe was 3.0% and CLR was 3.0 mL/h (Table 2). In the remaining 15 subjects, for whom all urine concentrations were below LLOQ, fe and CLR were estimated based on the urine volumes and the LLOQ value. Based on all 18 subjects, fe was estimated to be < 3.6% and CLR < 5.1 mL/h, in agreement with the 3 subjects with quantifiable results.

Safety

Overall, in arm A, 23 adverse events (AEs) were reported for 9 of 18 subjects (50.0%), none was serious or severe, and none led to subject withdrawal. The investigator considered 12 of 23 AEs to be nitisinone-related and 5 to be CYP-substrate related. In arm B, 11 AEs were reported for 7 of 18 subjects (38.9%); none was serious or severe, and none led to subject withdrawal. The investigator considered 6 of the 11 reported AEs to be nitisinone-related and 3 to be furosemide-related. All AEs in both arms recovered/resolved by the end of the study. One subject had clinically significant abnormal ophthalmological slit-lamp examination results with superficial keratitis and crystalline central keratopathy, which were considered related to nitisinone treatment. Findings were resolved at follow-up. Tyrosine values exceeded the normal ranges in all subjects, as expected, since nitisinone blocks the tyrosine metabolism and repeated dosing leads to increased serum levels of tyrosine. Tyrosine levels decreased after nitisinone treatment was stopped.

Discussion

In this clinical drug-drug interaction study, we show that nitisinone did not affect CYP2D6 activity but acted as a moderate inhibitor of CYP2C9, a weak inducer of CYP2E1, and a weak inhibitor of OAT1 and OAT3.

The effect of nitisinone on CYP2C9, OAT1, and OAT3 was in agreement with previous in vitro results [6]. However, nitisinone slightly reduced the exposure of the CYP2E1 substrate chlorzoxazone, indicating that this enzyme is weakly induced by nitisinone or that the absorption of chlorzoxazone is affected by nitisinone. While there are data indicating a weak inhibition of CYP2E1 in vitro, there is to our knowledge no in vitro data on the potential for nitisinone to induce CYP2E1; thus, the slight induction observed in this study may have masked an inhibitory effect of nitisinone on this enzyme. Also, to our knowledge, nitisinone does not affect gastrointestinal passage time, pH, or any other physiological factor which may be of importance for the absorption of chlorzoxazone. Therefore, there is no obvious reason to believe that the effect of nitisinone on chlorzoxazone pharmacokinetics would be due to an absorption-related interaction. Nitisinone had no effect on CYP2D6 in vivo, in contrast to the in vitro data that indicated a weak inhibition.

Conclusive results were reached for all substrates tested. Metoprolol, tolbutamide, and chlorzoxazone have been used as sensitive probe drugs for CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2E1 metabolic pathways and are recognized by health authorities worldwide for concomitant use in in vivo drug-drug interaction studies and/or drug labeling [1, 4, 14]. Furosemide is a recommended substrate for OAT1 and OAT3 [8] and like most substrate drugs of these transporters, furosemide a substrate of both and any potential clinically relevant effect of nitisinone was therefore likely to be revealed with this substrate. Furosemide was administered intravenously to avoid the large intraindividual variability in bioavailability seen after oral furosemide administration, which would have required a much larger sample size in arm B [15].

In two subjects, it was not possible to calculate AUC∞ for tolbutamide following administration of nitisinone due to too large extrapolated AUCs beyond the last sampling time point. These two subjects had the highest tolbutamide AUC∞ following administration of tolbutamide alone, and according to a sensitivity analysis, data for these two subjects had no impact on the conclusion that nitisinone causes a moderate inhibition of CYP2C9.

Based on the variability in the PK results following administration of tolbutamide alone (Supplementary Table 2 and individual values of t½ 5.28 to 12.8 h and AUC∞ ranging from 323 to 967 h·μg/mL), no poor metabolizer of CYP2C9 was included in the study [16]. In addition, the intersubject variability in the effect of nitisinone on the CYP2C9 substrate tolbutamide was moderate based on the 90% CI 2.11–2.53.

Dose levels of the substrates were the same as previously used in a cocktail study [9] except for metoprolol and tolbutamide. Dose levels of these two substrates were double to those used earlier and within clinically relevant levels [9].

Nitisinone steady state was reached after 12 days dosing, well in advance before administering the substrates. The nitisinone steady-state levels were well above clinically relevant plasma exposures (20 to 70 μM) [1, 17, 18], providing support that any relevant effect on transporters or CYP enzyme should have been captured in this study. Renal excretion appeared to be of minor importance, since < 4% of the nitisinone dose was excreted unchanged in the urine.

As expected, repeated administration of 80 mg nitisinone once daily was well tolerated and no safety concerns were identified during the study. Eye-related adverse reactions appearing as a consequence of elevated tyrosine levels are common [4] but in this study expected to be less frequent, since such reactions usually appear after several months of nitisinone treatment. Abnormally high, but not clinically relevant and transient, tyrosine levels were reported for all subjects starting after the first dose of nitisinone. This was expected, since even a single dose blocks the phenylalanine/tyrosine metabolism and repeated dosing is expected to lead to increased serum levels of tyrosine, in particular when not combined with diet restrictions as in this study. Increased ketone levels were observed in parallel with the increased tyrosine levels. These were most likely associated with an interference of the semiquantitative testing system, resulting in false-positive detection of ketone bodies by excreted phenylketones (phenolic acids) [4].

In conclusion, this drug-drug interaction study showed that patients treated with nitisinone who are concomitantly treated with a product with a narrow therapeutic window metabolized primarily by CYP2C9, such as warfarin and phenytoin, should be properly monitored.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CYP:

-

Cytochrome P450

- HT-1:

-

Hereditary tyrosinemia type 1

- LLOQ:

-

Lower limit of quantification

- OAT:

-

Organic anion transporters

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetics

References

de Laet C, Dionisi-Vici C, Leonard JV, McKiernan P, Mitchell G, Monti L, de Baulny HO, Pintos-Morell G, Spiekerkotter U (2013) Recommendations for the management of tyrosinaemia type 1. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-8-8

van Spronsen FJ, Thomasse Y, Smit GP, Leonard JV, Clayton PT, Fidler V, Berger R, Heymans HS (1994) Hereditary tyrosinemia type I: a new clinical classification with difference in prognosis on dietary treatment. Hepatology 20(5):1187–1191

Hall MG, Wilks MF, Provan WM, Eksborg S, Lumholtz B (2001) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of NTBC (2-(2-nitro-4-fluoromethylbenzoyl)-1,3-cyclohexanedione) and mesotrione, inhibitors of 4-hydroxyphenyl pyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD) following a single dose to healthy male volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 52(2):169–177

Orfadin® Capsules: Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000555/WC500049195.pdf. Accessed in Aug 2018

Olsson B, Cox TF, Psarelli EE, Szamosi J, Hughes AT, Milan AM, Hall AK, Rovensky J, Ranganath LR (2015) Relationship between serum concentrations of nitisinone and its effect on homogentisic acid and tyrosine in patients with alkaptonuria. JIMD Rep 24:21–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/8904_2015_412

Neat JNWA, Kazmi F, Prentiss P, Buckley B, Wilson EM, Bial J, Bagi CM, Grompe M, Parkinson A ((2010)) In vitro inhibition and induction of human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes by NTBC and its metabolism in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Rev 42(Supplement 1). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268136954_In_vitro_inhibition_and_induction_of_human_liver_cytochrome_P450_enzymes_by_NTBC_and_its_metabolism_in_human_liver_microsomes. Accessed in Nov 2018

European Medicines Agency (EMA) (2012) Committee for Human Medicinal Products (CHMP): guideline on the investigation of drug interactions. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/pages/includes/document/open_document.jsp?webContentId=WC500129606. Accessed in Aug 2018

Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Drug development and drug interactions: table of substrates, inhibitors and inducers. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/DrugInteractionsLabeling/ucm093664.htm. Accessed in Aug 2018

Sharma A, Pilote S, Belanger PM, Arsenault M, Hamelin BA (2004) A convenient five-drug cocktail for the assessment of major drug metabolizing enzymes: a pilot study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 58(3):288–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02162.x

Ingelman-Sundberg M, Sim SC, Gomez A, Rodriguez-Antona C (2007) Influence of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on drug therapies: pharmacogenetic, pharmacoepigenetic and clinical aspects. Pharmacol Ther 116(3):496–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.004

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (2017) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for industry: drug interaction studies—study design, data analysis, implications for dosing, and labeling recommendations. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM292362.pdf. Accessed in Aug 2018

Jack DB, Quarterman CP, Zaman R, Kendall MJ (1982) Variability of beta-blocker pharmacokinetics in young volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 23(1):37–42

Richard J, Cardot JM, Godbillon J (1994) Inter- and intra-subject variability of metoprolol kinetics after intravenous administration. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 19(2):157–162

Ernstgard L, Warholm M, Johanson G (2004) Robustness of chlorzoxazone as an in vivo measure of cytochrome P450 2E1 activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol 58(2):190–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02132.x

Granero GE, Longhi MR, Mora MJ, Junginger HE, Midha KK, Shah VP, Stavchansky S, Dressman JB, Barends DM (2010) Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: furosemide. J Pharm Sci 99(6):2544–2556. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.22030

Kirchheiner J, Bauer S, Meineke I, Rodhe W, Prang V, Miesel C, Roots I, Brockmöller J (2002) Impact of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms on tolbutamide kinetics and the insulin and glucose response in healthy volunteers. Pharmacogenetics 12:101–109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0107-7

Chinsky JM, Singh R, Ficicioglu C, van Karnebeek CDM, Grompe M, Mitchell G, Waisbren SE, Gucsavas-Calikoglu M, Wasserstein MP, Coakley K, Scott CR (2017) Diagnosis and treatment of tyrosinemia type I: a US and Canadian consensus group review and recommendations. Genet Med 19(12). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.101

Mayorandan S, Meyer U, Gokcay G, Segarra NG, de Baulny HO, van Spronsen F, Zeman J, de Laet C, Spiekerkoetter U, Thimm E, Maiorana A, Dionisi-Vici C, Moeslinger D, Brunner-Krainz M, Lotz-Havla AS, Cocho de Juan JA, Couce Pico ML, Santer R, Scholl-Burgi S, Mandel H, Bliksrud YT, Freisinger P, Aldamiz-Echevarria LJ, Hochuli M, Gautschi M, Endig J, Jordan J, McKiernan P, Ernst S, Morlot S, Vogel A, Sander J, Das AM (2014) Cross-sectional study of 168 patients with hepatorenal tyrosinaemia and implications for clinical practice. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9:107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-014-0107-7

Acknowledgements

We thank Margit Pelcman (Sobi, Sweden) for coordinating the clinical conduct, Tommy Andersson (Sobi, Sweden) for coordinating the bioanalytical analysis, and Juliette Janson (Sobi, Sweden) for predicting the nitisinone plasma exposure for this study. We also thank Kristina Lindsten (Sobi, Sweden) for medical writing support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp3).

Funding

This study was fully funded by Sobi (Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB [publ]), the marketing authorization holder of nitisinone (Orfadin®).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gunilla Huledal: Contributed to the conduct of the study and data analysis, and was the main author of the manuscript. As guarantor for the article she accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, has access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Birgitta Olsson: Contributed to the study design, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Kristin Önnestam: Contributed to the study design, study conduct, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Per Dalén: Contributed to the study design, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Daniel Lindqvist: Contributed to the data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Matthias Kruse: Contributed to the study design, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Anders Bröijersén: Contributed to the study design, data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the independent ethical committee “Geschäftsstelle der Ethik-Kommission des Landes Berlin” in Berlin, Germany.

Conflicts of interest

Gunilla Huledal: Employee of Sobi and holder of Sobi shares.

Birgitta Olsson: Former employee of Sobi, presently freelancing consultant. Holder of Sobi shares.

Kristin Önnestam: Employee of Sobi.

Per Dalén: Employee of Sobi and holder of Sobi shares.

Daniel Lindqvist: Employee of Sobi.

Matthias Kruse: Employee of Parexel, which was contracted to perform the study described in this manuscript.

Anders Bröijersén: Employee of Sobi.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huledal, G., Olsson, B., Önnestam, K. et al. Non randomized study on the potential of nitisinone to inhibit cytochrome P450 2C9, 2D6, 2E1 and the organic anion transporters OAT1 and OAT3 in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 313–320 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2581-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-018-2581-7