Abstract

Discrete derived categories were studied initially by Vossieck (J Algebra 243:168–176, 2001) and later by Bobiński et al. (Cent Eur J Math 2:19–49, 2004). In this article, we describe the homomorphism hammocks and autoequivalences on these categories. We classify silting objects and bounded t-structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In this article, we study the bounded derived categories of finite-dimensional algebras that are discrete in the sense of Vossieck [44]. Informally speaking, discrete derived categories can be thought of as having structure intermediate in complexity between the derived categories of hereditary algebras of finite representation type and those of tame type. Note, however, that the algebras with discrete derived categories are not hereditary. We defer the precise definition until the beginning of the next section.

Understanding homological properties of algebras means understanding the structure of their derived categories. We investigate several key aspects of the structure of discrete derived categories: the structure of homomorphism spaces, the autoequivalence groups of the categories, and the t-structures and co-t-structures inside discrete derived categories.

The study of the structure of algebras with discrete derived categories was begun by Vossieck, who showed that they are always gentle and classified them up to Morita equivalence. Bobiński et al. [9] obtained a canonical form for the derived equivalence class of these algebras; see Fig. 1. This canonical form is parametrised by integers \(n\ge r \ge 1\) and \(m>0\), and the corresponding algebra denoted by \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\). We restrict to parameters \(n>r\), which is precisely the case of finite global dimension. In [9], the authors also determined the components of the Auslander–Reiten (AR) quiver of derived-discrete algebras and computed the suspension functor.

The structure exhibited in [9] is remarkably simple, which brings us to our principal motivation for studying these categories: they are sufficiently straightforward to make explicit computation highly accessible but also non-trivial enough to manifest interesting behaviour. For example, discrete derived categories contain natural examples of spherelike objects in the sense of [22]. The smallest subcategory generated by such a spherelike object has been studied in [25, 32] and also in the context of (higher) cluster categories of type \(A_\infty \) in [24]. Indeed, in Proposition 6.4 we show that every discrete derived category contains two such higher cluster categories, up to triangle equivalence, as proper subcategories when the algebra has finite global dimension.

Furthermore, the structure of discrete derived categories is highly reminiscent of the categories of perfect complexes of cluster-tilted algebras of type \(\tilde{A}_n\) studied in [4]. This suggests approaches developed here to understand discrete derived categories are likely to find applications more widely in the study of derived categories of gentle algebras.

The basis of our work is giving a combinatorial description via AR quivers of which indecomposable objects admit non-trivial homomorphism spaces between them, so called ‘Hom-hammocks’. As a byproduct, we get the following interesting property of these categories: the dimensions of the homomorphism spaces between indecomposable objects have a common bound. In fact, in Theorem 6.1 we show there are unique homomorphisms, up to scalars, whenever \(r>1\), and in the exceptional case \(r=1\), the common dimension bound is 2. We believe this property holds independent interest and in [15], we investigate it further. See [20] for a different approach to capturing the ‘smallness’ of discrete derived categories. As another measure for categorical size, the Krull–Gabriel dimension of discrete derived categories has been computed in [10]; it is at most 2.

In Theorem 5.7 we explicitly describe the group of autoequivalences. For this, we introduce a generalisation of spherical twist functors arising from cycles of exceptional objects. The action of these twists on the AR components of \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) is a useful tool, which is frequently employed here.

In Sect. 7, we address the classification of bounded t-structures and co-t-structures in \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\), which are important in understanding the cohomology theories occurring in triangulated categories, and have recently become a focus of intense research as the principal ingredients in the study of Bridgeland stability conditions [13], and their co-t-structure analogues [29]. Further investigation into the properties of (co-)t-structures and the stability manifolds is conducted in the sequel [14]; see also [38].

We study (co-)t-structures indirectly via silting subcategories, which generalise tilting objects and behave like the projective objects of hearts of bounded t-structures. In general, one cannot get all bounded t-structures in this way, but in Proposition 7.1, we show that the heart of each bounded t-structure in \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) is equivalent to \(\mathsf {mod}(\Gamma )\), where \(\Gamma \) is a finite-dimensional algebra of finite representation type. The upshot is that using the bijections of König and Yang [33], classifying silting objects is enough to classify all bounded (co-)t-structures. We show that \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) admits a semi-orthogonal decomposition into \(\mathsf {D}^b({\mathbf {k}}A_{n+m-1})\) and the thick subcategory generated by an exceptional object. Using Aihara and Iyama’s silting reduction [1], we classify the silting objects in Theorem 7.22. We finish with an explicit example of \(\Lambda (2,3,1)\) in Sect. 8.

2 Discrete derived categories and their AR-quiver

We always work over a fixed algebraically closed field \({\mathbf {k}}\). All modules will be finite-dimensional right modules. Throughout, all subcategories will be additive and closed under isomorphisms.

2.1 Discrete derived categories

We are interested in \({\mathbf {k}}\)-linear, Hom-finite triangulated categories which are small in a certain sense. One precise definition of such smallness is given by Vossieck [44]; here we present a slight generalisation of his notion.

Definition 2.1

A derived category (or, more generally and intrinsically, a Hom-finite triangulated category with a bounded t-structure) \(\mathsf D\) is discrete (with respect to this t-structure), if for every map \(v:{\mathbb {Z}}\rightarrow K_0(\mathsf D)\) there are only finitely many isomorphism classes of objects \(D\in \mathsf D\) with \([H^i(D)]=v(i)\in K_0(\mathsf D)\) for all \(i\in {\mathbb {Z}}\).

Let us elaborate on the connection to [44]: Vossieck speaks of finitely supported, positive dimension vectors \(v\in K_0(\mathsf D)^{({\mathbb {Z}})}\) which he can do since he has \(\mathsf D=\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) for a finite-dimensional algebra \(\Lambda \), so \(K_0(\Lambda )\cong {\mathbb {Z}}^r\). In our slight generalisation of his notion, we cannot do so, but for finite-dimensional algebras the new notion gives back the old one: if v is negative somewhere, there will be no objects of that dimension vector whatsoever. For the same reason, we don’t have to assume that v has finite support: if it doesn’t, the set of objects of that class is empty.

Note that our definition of discreteness appears to depend on the choice of bounded t-structure. Throughout this article, we shall be interested in the bounded derived category \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) of a finite-dimensional algebra \(\Lambda \). We shall always use discreteness with respect to the standard t-structure, whose heart is \(\mathsf {mod}(\Lambda )\), the category of finite-dimensional right \(\Lambda \)-modules. However, in [15], the results of this article will be used to show that the categories studied here are discrete with respect to any bounded t-structure.

Obviously, derived categories of path algebras of type ADE Dynkin quivers are examples of discrete categories. Moreover, [44] shows that the bounded derived category of a finite-dimensional algebra \(\Lambda \), which is not of derived-finite representation type, is discrete if and only if \(\Lambda \) is Morita equivalent to the bound quiver algebra of a gentle quiver with exactly one cycle having different numbers of clockwise and anticlockwise orientations.

Furthermore, in [9], Bobiński, Geiß and Skowroński give a derived Morita classification of such algebras. More precisely, for \(\Lambda \) connected and not of Dynkin type, the derived category \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) is discrete if and only if \(\Lambda \) is derived equivalent to the path algebra \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) for the quiver with relations given in Fig. 1, and some values of r, n, m.

2.2 The AR quiver of \(\varvec{\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))}\)

The algebra \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) has finite global dimension if and only if \(n>r\). In the following, we always make this assumption. Therefore the derived category \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) enjoys duality in the form

functorially in \(A,B\in \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\), where the Serre functor \(\mathsf {S}\) is given by the Nakayama functor, i.e. \(\mathsf {S}= \nu \,{:}{=}\, {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}_{\Lambda }(-,\Lambda )^*\); see [21, § 4.6]. In other words, \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) has Auslander–Reiten triangles and translation \(\tau \,{:}{=}\, \Sigma ^{-1}\mathsf {S}\). We will use both notations, depending on the context. Some general properties of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) are: this triangulated category is algebraic, Hom-finite, Krull–Schmidt and indecomposable; see Appendix A.1 for details.

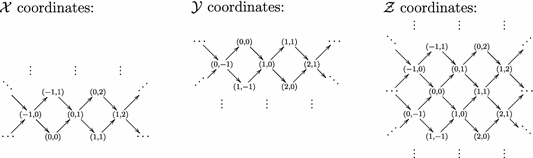

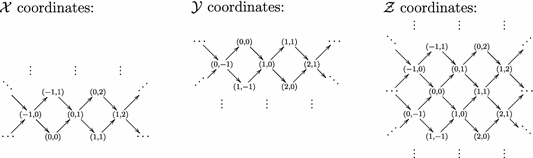

We collect together some more special properties of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) which will be crucial throughout the paper; the reference is [9]. By [9, Theorem B], the AR quiver of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) has precisely 3r components; these are denoted by

The \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathcal {Y}\) components are of type \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \), whereas the \(\mathcal {Z}\) components are of type \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty ^\infty \). It will be convenient to have notation for the subcategories generated by indecomposable objects of the same type:

For each \(k= 0,\ldots , r-1\), we label the indecomposable objects in \(\mathcal {X}^k, \mathcal {Y}^k, \mathcal {Z}^k\) as follows:

Properties 2.2

This labelling is chosen in such a way that the following properties hold:

-

(1)

Irreducible morphisms go from an object with coordinate (i, j) to objects \((i+1,j)\) and \((i,j+1)\) in the same component (when they exist).

-

(2)

The AR translate of an object with coordinate (i, j) is the object with coordinate \((i-1,j-1)\) in the same component, i.e. \(\tau X^k_{i,j} = X^k_{i-1,j-1}\) etc.

-

(3)

The suspension of indecomposable objects is given below, with \(k=0,\ldots ,r-2\):

In particular, \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {X}= \tau ^{-m-r}\) and \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {Y}= \tau ^{n-r}\) on objects.

-

(4)

There are distinguished triangles, for any \(i,j,d\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) with \(d\ge 0\):

-

(5)

There are chains of non-zero morphisms for any \(i\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) and \(k=0,\ldots ,r-1\):

Later, we will often use the ‘height’ of indecomposable objects in \(\mathcal {X}\) or \(\mathcal {Y}\) components. For \(X^k_{ij} \in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X}^k)\), we set \(h(X^k_{ij}) = j-i\) and call it the height of \(X^k_{ij}\) in the component \(\mathcal {X}^k\). Similarly, for \(Y^k_{ij} \in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Y}^k)\), we set \(h(Y^k_{ij}) = i-j\) and call it the height of \(Y^k_{ij}\) in the component \(\mathcal {Y}^k\). The mouth of an \(\mathcal {X}\) or \(\mathcal {Y}\) component consists of all objects of height 0.

3 Hom spaces: hammocks

For brevity, we will write \(\Lambda \, {:}{=}\, \Lambda (r,n,m)\). In this section, for a fixed indecomposable object \(A\in \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) we compute the so-called ‘Hom-hammock’ of A, i.e. the set of indecomposables \(B\in \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) with \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0\). By duality, this also gives the contravariant Hom-hammocks: \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(-,A) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathsf {S}^{-1}A,-)^*\). Therefore we generally refrain from listing the \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(-,A)\) hammocks explicitly.

The precise description of the hammocks is slightly technical. However, the result is quite simple, and the following schematic indicates the hammocks \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,-)\ne 0\) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(Z,-)\ne 0\) for indecomposables \(X\in \mathcal {X}\) and \(Z\in \mathcal {Z}\):

3.1 Hammocks from the mouth

We start with a description of the Hom-hammocks of objects at the mouths of all \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \) components. The proof relies on Happel’s triangle equivalence of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) with the stable module category of the repetitive algebra of \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\). As the repetitive algebras are special biserial algebras, the well-known theory of string (and band) modules provides a useful tool to understand the indecomposable objects and homomorphisms between them; we summarise this theory Appendix B.

To make our statements of Hom-hammocks more readable, we employ the language of rays and corays. Let \(V=V_{i,j}\) be an indecomposable object of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) with coordinates (i, j). Recall the conventions that \(j\ge i\) if \(V\in \mathcal {X}\) whereas \(i\ge j\) if \(V\in \mathcal {Y}\). Denoting the AR component of V by \({\mathcal C}\) and its objects by \(V_{a,b}\), the following six definitions give the rays/corays from/to/through V, respectively

Note that, because of the orientation of the components, the (positive) ray of an indecomposable \(X^k_{ii}\in \mathcal {X}^k\) at the mouth consists of indecomposables in \(\mathcal {X}^k\) reached by arrows going out of \(X^k_{ii}\), while in the \(\mathcal {Y}\) components the (negative) ray of \(Y^k_{ii}\) contains objects which have arrows going in to it.

For the next statement, whose proof is deferred to Lemma B.7, recall that the Serre functor is given by suspension and AR translation: \(\mathsf {S}= \Sigma \tau \). Also, rays and corays commute with these three functors.

Lemma 3.1

Let \(A \in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m)))\) with \(r>1\) and let \(i,k\in {\mathbb {Z}}\), \(0\le k<r\). Then

and in all other cases the Hom spaces are zero. For \(r=1\) the Hom-spaces are as above, except \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X^0_{ii},X^0_{i,i+m}) = {\mathbf {k}}^2\).

3.2 Hom-hammocks for objects in \(\mathcal {X}\) components

Assume \(A=X^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X}^k)\). In order to describe the various Hom-hammocks conveniently, we set

-

\(A_0 \,{:}{=}\, X^k_{jj}\) to be the intersection of the coray through A with the mouth of \(\mathcal {X}^k\), and

-

\(_0 A \,{:}{=}\, X^k_{ii}\) to be the intersection of the ray through A with the mouth of \(\mathcal {X}^k\).

By definition, \(A_0\) and \(_0 A\) have height 0. If A sits at the mouth, then \(A = A_0 = {}_0A\).

We now write down some standard triangles involving the objects \(_0 A\), \(A_0\) and A. The following lemma is completely general and holds in any \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \) component of the AR quiver of a Krull–Schmidt triangulated category—we use the notation introduced above for the \(\mathcal {X}\) components of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\).

Lemma 3.2

Let A be an indecomposable object of height \(h(A) \ge 1\) in a \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \) component of a Krull–Schmidt triangulated category. Let  be the AR triangle with A at its apex; assuming \(C = 0\) if \(h(A)=1\). Then there are triangles

be the AR triangle with A at its apex; assuming \(C = 0\) if \(h(A)=1\). Then there are triangles

where \(u'\) and \(v''\) are induced by u and v, respectively.

Proof

By Lemma 3.1 the composition, \({}_0A \rightarrow A\), of irreducible maps along a ray is non-zero. Likewise the composition, \(A \rightarrow A_0\), of irreducible maps along a coray is non-zero.

We proceed by induction on \(h(A)\). If \(h(A) = 1\), then both triangles coincide with the AR triangle \({}_0A \rightarrow A \rightarrow A_0 \rightarrow \Sigma {}_0A\); in particular, \(A' = {}_0 A\) and \(A'' = A_0\).

Assume \(h(A) > 1\). We shall show the existence of one triangle, the other one is dual. Consider the AR triangle together with the split triangle  . These triangles fit into the following commutative diagram arising from the octahedral axiom.

. These triangles fit into the following commutative diagram arising from the octahedral axiom.

Note that \(u'' \ne 0\) since it is irreducible. Since \(h(A') = h(A) - 1\) and the fact that \(A'\) sits at the apex of an AR triangle \((A')' \rightarrow A' \oplus C' \rightarrow C \rightarrow \Sigma (A')'\), one can show by induction that there is a triangle  . Thus \(D = \Sigma (_0 A')\). From \(_0 A' = {}_0A\) we get the desired triangle as the rightmost vertical triangle in the diagram above. \(\square \)

. Thus \(D = \Sigma (_0 A')\). From \(_0 A' = {}_0A\) we get the desired triangle as the rightmost vertical triangle in the diagram above. \(\square \)

We introduce notation for line segments in the AR quiver: given two indecomposable objects \(A,B\in \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) which lie on a ray or coray (so in particular sit in the same component), then the finite set consisting of these two objects and all indecomposables lying between them on the (co)ray is denoted by \(\overline{AB}\). Finally, we recall our convention that \(\mathcal {X}^r=\mathcal {X}^0\) and note that \(_0(\mathsf {S}A) = \Sigma \tau ({}_0A)\).

Lemma 3.3

Consider \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) with \(r > 1\). If \(A \in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X}) \cup \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Y})\) then for each indecomposable object \(B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\) we have \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \ne 0\).

Note that we shall treat the case \(r=1\) in Proposition 6.2 below; we continue to use the notation for the \(\mathcal {X}\) components, however, the argument applies also to the \(\mathcal {Y}\) components.

Proof

Let A be an indecomposable object in an \(\mathcal {X}\) component. Let \(B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\). If \(B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A) \cup \overline{AA_0} \cup \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A_0)\) (see Fig. 2), then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \ne 0\), using Serre duality and Lemma 3.1 if \(B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A_0)\) (Fig. 2).

By the considerations above, we may assume that B lies in the interior of the region \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\). Consider the following part of the AR quiver of \(\mathsf {D}\):

where \(B''\) is one irreducible morphism closer to \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A_0)\) and \({}_0 B \rightarrow B \rightarrow B'' \rightarrow \Sigma ({}_0 B)\) is the triangle from Lemma 3.2. Moreover, since \(\Sigma \) is an autoequivalence, any (co)suspension of \({}_0 B\) and \(B_0\) must also lie on the mouth.

We proceed by induction up each ray in the interior of the hammock starting with the ray closest to \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A_0)\). By induction, \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B'') \ne 0\). Since \({}_0 B \ne A_0\) because \(B \notin \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A_0)\), we have \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,{}_0 B) = 0\) by Lemma 3.1. Applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,-)\) to the triangle involving \(B''\) above produces a long exact sequence in which the vanishing of \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\Sigma ({}_0 B))\) gives \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \ne 0\). By Lemma 3.1, A admits nontrivial morphisms to precisely \(A_0\) and \(\mathsf {S}({}_0 A)\) on the mouth of an \(\mathcal {X}\) component. Since \(r \ge 2\), \(\Sigma ({}_0 B)\) and \({}_0 A\) lie in different components of the AR quiver so \(\Sigma ({}_0 B) \ne {}_0 A\). If \(\Sigma ({}_0 B) = \mathsf {S}({}_0 A)\) then \({}_0 B = \tau ({}_0 A)\), which contradicts \(B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\). Hence, \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\Sigma ({}_0 B)) = 0\).\(\square \)

Proposition 3.4

(Hammocks \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {X}^k,-)\)) Let \(A=X^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X}^k)\) and assume \(r>1\).

For any indecomposable object \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\) the following cases apply:

- \(B\in \mathcal {X}^k\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\overline{{}_0(\mathsf {S}A),\mathsf {S}A})\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^k\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(\overline{Z^k_{ii}Z^k_{ji}})\)

and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)=0\) for all other \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\).

For \(r=1\), these results still hold, except that the \(\mathcal {X}\)-clauses are replaced by

- \(B\in \mathcal {X}^0\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0}) \cup \mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\overline{_0(\tau ^{-m}A),\tau ^{-m}A})\).

Proof

The main tool in the proof of this, and the following propositions, will be induction on the height of A—the induction base step is proved in Lemma 3.1 which gives the hammocks for indecomposables of height 0. We give a careful exposition for the first claim, and for \(r>1\). The \(r=1\) case will be treated in Proposition 6.2.

Case \(B\in \mathcal {X}^k\): For any indecomposable object \(A\in \mathcal {X}^k\), write R(A) for the subset of \(\mathcal {X}^k\) specified in the statement, i.e. bounded by the rays out of A and \(A_0\), and the line segment \(\overline{AA_0}\). The existence of non-zero homomorphisms \(A\rightarrow B\) for objects \(B\in R(A)\) follows directly from Lemma 3.3.

For the vanishing statement, we proceed by induction on the height of A. If A sits on the mouth of \(\mathcal {X}^k\), then Lemma 3.1 states indeed that the \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0\) if and only if B is in the ray of A. Note that R(A) is precisely \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A)\) in this case.

Now let \(A\in \mathcal {X}^k\) be any object of height \(h\,{:}{=}\,h(A)>0\). We consider the diamond in the AR mesh which has A as the top vertex, and the corresponding AR triangle \(A'\rightarrow A\oplus C\rightarrow A''\rightarrow \Sigma A'\), where \(h(A') = h(A'') = h-1\) and \(h(C) = h-2\). (If \(h=1\), we are in the degenerate case with \(C=0\).) It is clear from the definitions that \(A_0=A''_0\), \(A'_0=C_0\) and there are inclusions \(R(A'')\subset R(A)\subset R(A')\cup R(A'')\). We start with an object \(B\in \mathcal {X}^k\) such that \(B\notin R(A')\cup R(A'')\). By the induction hypothesis, we know that \(R(A')\), R(C) and \(R(A'')\) are the Hom-hammocks in \(\mathcal {X}^k\) for \(A'\), C, \(A''\), respectively. Since B is contained in none of them, we see that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A',B)={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(C,B)={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A'',B)=0\). Applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(-,B)\) to the given AR triangle shows \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)=0\).

It remains to show that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,D)=0\) for objects \(D \in (R(A')\cup R(A'')) \backslash R(A)\) which can be seen to be the line segment \(\overline{A'A'_0}\). Again we work up from the mouth: \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,A'_0)= 0\) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\tau A'_0)=0\) by Lemma 3.1, as before. The extension \(D_1\) given by \(\tau A'_0\rightarrow D_1\rightarrow A'_0\rightarrow \Sigma \tau A'_0{}{}{}\) is the indecomposable object of height 1 on \(\overline{A'A'_0}\). Applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,-)\) to this triangle, we find \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,D_1)=0\), as required. The same reasoning works for the objects of heights \(2,\ldots ,h-1\) on the segment.

Case \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\): We start by showing the existence of non-zero homomorphisms to indecomposable objects in the desired region. For any B in this region, it follows directly from the dual of Lemma 3.3 that there is a non-zero homomorphism from B to \(\mathsf {S}A\). However, by Serre duality we see that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(B, \mathsf {S}A)^* \ne 0\), as required. The statement that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) = 0\) for all other \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\) can be proved by an induction argument which is analogous to the one given in the first case above.

Case \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^k\): For any indecomposable object \(A=X^k_{ij}\in \mathcal {X}^k\), write V(A) for the region in \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) specified in the statement, i.e. the region bounded by the rays through \(Z^k_{ii}\) and \(Z^k_{ji}\). We start by proving that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \ne 0\) for \(B \in V(A)\). The first chain of morphisms in Properties 1.2(5), implies that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0\) for any \(B\in \mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(Z^k_{ii})\). For any other \(B'=Z^{k}_{i+s,t} \in V(A)\), so \(t \in {\mathbb {Z}}\) and \(s \in \{1,\ldots ,h(A) = j-i\}\), we consider the special triangle \(X^k_{i,i+s-1}\rightarrow B\rightarrow B'\rightarrow \Sigma X^k_{i,i+s-1}{}{}{}\) from Properties 1.2(4), where \(B=Z^k_{it}\in \mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(Z^k_{ii})\). Applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,-)\) leaves us with the exact sequence

By looking at the Hom-hammocks in the \(\mathcal {X}\)-components that we already know, we see that the left-hand term vanishes as \(X^k_{i,i+s-1}\) is on the same ray as A but has strictly lower height. Similarly, we observe that the right-hand term of the sequence vanishes: \(0 = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X^k_{i,i+s-1}, \tau A) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\Sigma X^k_{i,i+s-1})\). Hence \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B') = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \ne 0\).

For the Hom-vanishing part of the statement, we again use induction on the height \(h\,{:}{=}\,h(A)\ge 0\). For \(h=0\), Lemma 3.1 gives \(V(A)=\mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(Z^k_{ii})\). For \(h>0\), as before we consider the AR mesh which has A as its top vertex: \(A'\rightarrow A\oplus C\rightarrow A''\rightarrow \Sigma A'{}{}{}\). For any \(Z\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z}^k)\), we apply \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(-,Z)\) to this triangle and find that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,Z)\ne 0\) implies \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A',Z)\ne 0\) or \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A'',Z)\ne 0\). Therefore \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) = 0\) for all \(B \notin V(A')\cup V(A'') = V(A)\), where the final equality is clear from the definitions.

Remaining cases: These comprise vanishing statements for entire AR components, namely \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {X}^k,\mathcal {X}^j)=0\) for \(j\ne k,k+1\), and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {X}^k,\mathcal {Y}^j)=0\) for any j, and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {X}^k,\mathcal {Z}^j)=0\) for \(j\ne k\). All of those follow at once from Lemma 3.1: with no non-zero maps from A to the mouths of the specified components of type \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathcal {Y}\), Hom vanishing can be seen using induction on height and considering a square in the AR mesh. The vanishing to the \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) components with \(k\ne j\) follows similarly. \(\square \)

3.3 Hom-hammocks for objects in \(\mathcal {Y}\) components

Assume \(A=Y^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Y}^k)\). This case is similar to the one above. Put

-

\(^0\! A \,{:}{=}\, Y^k_{ii}\) to be the intersection of the coray through A with the mouth of \(\mathcal {Y}^k\), and

-

\(A^0 \,{:}{=}\, Y^k_{jj}\) to be the intersection of the ray through A with the mouth of \(\mathcal {Y}^k\).

Proposition 3.5

(Hammocks \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {Y}^k,-))\) Let \(A=Y^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Y}^k)\) and assume \(r>1\).

For any indecomposable object \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\) the following cases apply:

- \(B\in \mathcal {Y}^k\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA^0})\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Y}^{k+1}\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\overline{{}^0(\mathsf {S}A),\mathsf {S}A})\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^k\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! \pm }(\overline{Z^k_{ii}Z^k_{ij}})\)

and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)=0\) for all other \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\).

For \(r=1\), these results still hold, except that the \(\mathcal {Y}\)-clauses are replaced by

- \(B\in \mathcal {Y}^0\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA^0}) \cup \mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\overline{^0(\tau ^n A),\tau ^n A})\).

Proof

These statements are analogous to those of Proposition 3.4. \(\square \)

3.4 Hom-hammocks for objects in \(\mathcal {Z}\) components

Let \(A = Z^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z}^k)\). By Lemma 3.1 we know that the following objects are well defined:

-

\(A_0 \,{:}{=}\) the unique object at the mouth of an \(\mathcal {X}\) component for which \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A, A_0) \ne 0\),

-

\(A^0 \,{:}{=}\) the unique object at the mouth of a \(\mathcal {Y}\) component for which \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A, A^0) \ne 0\).

In fact, \( A_0 \in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\) and \(A^0 \in \mathcal {Y}^{k+1}\).

Proposition 3.6

(Hammocks \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(\mathcal {Z}^k,-))\) Let \(A=Z^k_{ij}\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z}^k)\) and assume \(r>1\).

For any indecomposable object \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\) the following cases apply:

- \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(A_0))\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Y}^{k+1}\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(A^0))\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^k\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(A))\);

- \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^{k+1}\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {S}A))\)

and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)=0\) for all other \(B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ))\).

For \(r=1\), these results still hold, with the \(\mathcal {Z}\)-clauses replaced by

- \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^0\)::

-

then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(A)) \cup \mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {S}A))\).

The hammocks described in Proposition 3.6 are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Proof

The cases \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\) and \(B\in \mathcal {Y}^{k+1}\) follow by Serre duality from Proposition 3.4 and Proposition 3.5, respectively.

Thus let \(B=Z^l_{ab}\in \mathcal {Z}^l\) be an indecomposable object in a \(\mathcal {Z}\) component. There are two special distinguished triangles associated with B; see Properties 1.2(4):

where \({}_0B=X^l_{aa}\) is the unique object at the mouth of a \(\mathcal {X}\) component with \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}({}_0B,B)\ne 0\) and similarly \({}^0B=Y^l_{bb}\) is unique at a \(\mathcal {Y}\) mouth with \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}({}^0B,B)\ne 0\). We get two exact sequences by applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,-)\):

Case \(l\ne k, k+1\): In this case \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B')={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B'')\) follows from the above triangles via these exact sequences and Lemma 3.1. But this implies \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,Z)\) for all \(Z \in \mathcal {Z}^l\) and in particular \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\Sigma ^{cr}B)\) for all \(c\in {\mathbb {Z}}\). It follows that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)=0\) as \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) has finite global dimension.

Case \(l=k\): Again, we first show that the dimension function \(\hom (A,-)\) is constant on certain regions of \(\mathcal {Z}^k\). In particular, we have

Half of the first equality follows through the chain of equivalences

Likewise one obtains \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\Sigma {}_0B) \ne 0 \Longleftrightarrow B \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(\tau A)\), giving the first equality. Using the other triangle, the second equality is analogous.

The component \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) is divided by \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(\tau A)\) and \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! \pm }(\tau A)\) into four regions:

- \({\mathcal U}:\) :

-

The upwards-open region including \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\tau A) \backslash \{\tau A\}\) but excluding \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\tau A)\);

- \({\mathcal L}:\) :

-

The left-open region including \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\tau A) \cup \mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\tau A)\);

- \({\mathcal D}:\) :

-

The downwards-open region including \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(\tau A)\backslash \{\tau A\}\) but excluding \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\tau A)\);

- \({\mathcal R}:\) :

-

The right-open region excluding \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! \pm }(\tau A) \cup \mathsf {coray}_{\! \pm }(\tau A)\).

Using (1) above coupled with the fact that \({\mathcal U}\) contains infinitely many objects \(\Sigma ^{-rc} A\) with \(c \in {\mathbb {N}}\), shows by the finite global dimension of \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) that no objects in \({\mathcal U}\) admit non-trivial morphisms from A. Using (2) and analogous reasoning shows that no objects in \({\mathcal D}\) admit non-trivial morphisms from A. Non-existence of non-trivial morphisms from A to objects in \({\mathcal L}\) follows as soon as \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,\tau A) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^1(A,A)=0\) by using (2) above. The existence of the stalk complex of a projective module in the \(\mathcal {Z}\) component, Lemma B.9, coupled with the transitivity of the action of the automorphism group of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) on the \(\mathcal {Z}\) component, which is proved in Sect. 5 using only Lemma 3.1, shows that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^1(A,A)=0\) for all \(A\in \mathcal {Z}\).

Finally, \({\mathcal R}= \mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A))\) is the non-vanishing hammock simply by \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,A)\ne 0\) and using either (1) or (2).

Case \(l=k+1\): This is analogous to the previous case.\(\square \)

Remark 3.7

In the case that \(r>1\), Propositions 3.4, 3.5 and 3.6 say that each component of the AR quiver of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) is standard, i.e. that there are no morphisms in the infinite radical. Note that the components are not standard when \(r=1\).

4 Twist functors from exceptional cycles

In this purely categorical section, we consider an abstract source of autoequivalences coming from exceptional cycles. These generalise the tubular mutations from [35] as well as spherical twists. In fact, a quite general and categorical construction has been given in [43]. However, for our purposes this is still a little bit too special, as the Serre functor will act with different degree shifts on the objects in our exceptional cycles. We also give a quick proof using spanning classes.

Let \(\mathsf D\) be a \({\mathbf {k}}\)-linear, Hom-finite, algebraic triangulated category. Assume that \(\mathsf D\) has a Serre functor \(\mathsf {S}\) and is indecomposable; see Appendix A.1 for these notions. Recall that an object \(E\in \mathsf D\) is called exceptional if \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E,E)={\mathbf {k}}\cdot {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}_E\). For any object \(A\in \mathsf D\) we define the functor

and note that there is a canonical evaluation morphism \(\mathsf {F}\!_A\rightarrow {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) of functors. Also note that for two objects \(A_1,A_2\in \mathsf D\) there is a common evaluation morphism \(\mathsf {F}\!_{A_1}\oplus \mathsf {F}\!_{A_2}\rightarrow {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\). In fact, for any sequence of objects \(A_*=(A_1,\ldots ,A_n)\), we define the associated twist functor \(\mathsf {T}\!_{A_*}\) as the cone of the evaluation morphism—this gives a well-defined, exact functor by our assumption that \(\mathsf {D}\) is algebraic; see [22, §2.1] for details:

These functors behave well under equivalences:

Lemma 4.1

Let  be a triangle equivalence of algebraic \({\mathbf {k}}\)-linear triangulated categories induced from a dg functor, and let \(A_{*}=(A_1,\ldots ,A_n)\) be any sequence of objects. Then there are functor isomorphisms \(\mathsf {F}\!_{\varphi (A_*)} = \varphi \mathsf {F}\!_{A_{*}}\varphi ^{-1}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_{\varphi (A_*)} = \varphi \mathsf {T}\!_{A_{*}}\varphi ^{-1}\).

be a triangle equivalence of algebraic \({\mathbf {k}}\)-linear triangulated categories induced from a dg functor, and let \(A_{*}=(A_1,\ldots ,A_n)\) be any sequence of objects. Then there are functor isomorphisms \(\mathsf {F}\!_{\varphi (A_*)} = \varphi \mathsf {F}\!_{A_{*}}\varphi ^{-1}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_{\varphi (A_*)} = \varphi \mathsf {T}\!_{A_{*}}\varphi ^{-1}\).

Proof

This follows the standard argument for spherical twists: For \(\mathsf {F}\!_{A_*}\) we have

Conjugating the evaluation functor morphism \(\mathsf {F}\!_{A_*}\rightarrow {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) with \(\varphi \), we find that \(\varphi \mathsf {T}\!_{A_*}\varphi ^{-1}\) is the cone of the conjugated evaluation functor morphism \(\mathsf {F}\!_{\varphi (A_*)}\rightarrow {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) which is the evaluation morphism for \(\varphi (A_*)\). Hence that cone is \(\mathsf {T}\!_{\varphi (A_*)}\). \(\square \)

Definition 4.2

A sequence \((E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) of objects of \(\mathsf D\) is an exceptional n-cycle if

-

(1)

every \(E_i\) is an exceptional object,

-

(2)

there are integers \(k_i\) such that \(\mathsf {S}(E_i)\cong \Sigma ^{k_i}(E_{i+1})\) for all i (where \(E_{n+1}{:}{=}E_1\)),

-

(3)

\({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_i,E_j)=0\) unless \(j=i\) or \(j=i+1\).

This definition assumes \(n\ge 2\) but a single object E should be considered an ‘exceptional 1-cycle’ if E is a spherical object, i.e. there is an integer k with \(\mathsf {S}(E)\cong \Sigma ^k(E)\) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E,E)={\mathbf {k}}\oplus \Sigma ^{-k}{\mathbf {k}}\). In this light, the above definition, and statement and proof of Theorem 4.5 are generalisations of the treatment of spherical objects and their twist functors as in [27, §8].

In an exceptional cycle, the only non-trivial morphisms among the \(E_i\) apart from the identities are given by \(\alpha _i: E_i\rightarrow \Sigma ^{k_i}E_{i+1}\). This explains the terminology: the subsequence \((E_1,\ldots ,E_{n-1})\) is an honest exceptional sequence, but the full set \((E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) is not—the morphism \(\alpha _n: E_n\rightarrow \Sigma ^{k_n}E_1\) prevents it from being one, and instead creates a cycle.

Remark 4.3

All objects in an exceptional n-cycle are fractional Calabi–Yau: since \(\mathsf {S}(E_i)\cong \Sigma ^{k_i}E_{i+1}\) for all i, applying the Serre functor n times yields \(\mathsf {S}^n(E_i)\cong \Sigma ^k E_i\), where \(k{:}{=}k_1+\cdots +k_n\). Thus the Calabi–Yau dimension of each object in the cycle is k / n.

Example 4.4

We mention that this severely restricts the existence of exceptional n-cycles of geometric origin: Let X be a smooth, projective variety over \({\mathbf {k}}\) of dimension d and let \(\mathsf D{:}{=}\mathsf {D}^b(\mathsf {coh} X)\) be its bounded derived category. The Serre functor of \(\mathsf D\) is given by \(\mathsf {S}(-) = \Sigma ^d(-)\otimes \omega _X\) and in particular, is given by an autoequivalence of the standard heart followed by an iterated suspension. If \(E_*\) is any exceptional n-cycle in \(\mathsf D\), we find \(\mathsf {S}^n(E_i)=\Sigma ^{dn} E_i\otimes \omega ^n_X \cong \Sigma ^k E_i\), hence \(k=k_1+\cdots +k_n=dn\) and \(E_i\otimes \omega _X^n\cong E_i\). If furthermore the exceptional n-cycle \(E_*\) consists of sheaves, then this forces \(k_i=d\) to be maximal for all i, as non-zero extensions among sheaves can only exist in degrees between 0 and d. However, \(\mathsf {S}E_i=\Sigma ^d E_i\otimes \omega _X\cong \Sigma ^d E_{i+1}\) implies \(E_{i+1}\cong E_i\otimes \omega _X\) for all i.

As an example, let X be an Enriques surface. Its structure sheaf \({\mathcal O}_X\) is exceptional, and the canonical bundle \(\omega _X\) has minimal order 2. In particular, \(({\mathcal O}_X,\omega _X)\) forms an exceptional 2-cycle and, by the next theorem, gives rise to an autoequivalence of \(\mathsf {D}^b(X)\).

Theorem 4.5

Let \(E_* = (E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) be an exceptional n-cycle in \(\mathsf D\). Then the twist functor \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) is an autoequivalence of \(\mathsf D\).

Proof

We define two classes of objects of \(\mathsf D\) by \(\mathsf {E}{:}{=}\{ \Sigma ^l E_i \mid l\in {\mathbb {Z}}, i=1,\ldots ,n \}\) and \(\Omega \,{:}{=}\, \mathsf {E}\cup \mathsf {E}^\perp \). Note that \(\mathsf {E}\) and hence \(\Omega \) are closed under suspensions and cosuspensions. It is a simple and standard fact that \(\Omega \) is a spanning class for \(\mathsf D\), i.e. \(\Omega ^\perp =0\) and \({}^\perp \Omega =0\); the latter equality depends on the Serre condition \(\mathsf {S}(E_i)\cong \Sigma ^{k_i}(E_{i+1})\). Note that spanning classes are often called ‘(weak) generating sets’ in the literature.

Step 1: We start by computing \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) on the objects \(E_i\) and the maps \(\alpha _i\). For notational simplicity, we will treat \(E_1\) and \(\alpha _1: E_1\rightarrow \Sigma ^{k_1}E_2\). It follows immediately from the definition of exceptional cycle that \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}(E_1)=E_1\oplus \Sigma ^{-k_n}E_n\). The cone of the evaluation morphism is easily seen to sit in the following triangle

so that \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(E_1) = \Sigma ^{1-k_n}E_n\). The left-hand morphism has an obvious splitting, this implies the zero morphism in the middle. The third map is indeed the one specified above; this can be formally checked with the octahedral axiom, or one can use the vanishing of the composition of two adjacent maps in a triangle.

Likewise, we find \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}(E_2)=\Sigma ^{-k_1}E_1\oplus E_2\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(E_2) = \Sigma ^{1-k_1}E_1\). Now consider the following diagram of distinguished triangles, where the vertical maps are induced by \(\alpha _1\):

Hence, the commutativity of the right-hand square forces \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(\alpha _1) = -\Sigma ^{1-k_n}\alpha _n\).

This also works if \(n=2\) and \(k_1=-k_2\) (with unchanged left-hand vertical arrow).

Step 2: The above computation shows that the functor \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) is fully faithful when restricted to \(\mathsf {E}\). It is also obvious from the construction of the twist that \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) is the identity when restricted to \(\mathsf {E}^\perp \).

Let \(E_i\in \mathsf {E}\) and \(X\in \mathsf {E}^\perp \). Then \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_i,X)=0\) and also \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(E_i),\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(X))={{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\Sigma ^{1-k_{i-1}}E_{i-1},X)=0\). Finally, we use Serre duality and the defining property of \(E_*\) to see that

Combining all these statements, we deduce that \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) is fully faithful when restricted to the spanning class \(\Omega \), hence bona fide fully faithful by general theory; see e.g. [27, Proposition 1.49]. Note that \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) has left and rights adjoints as the identity and \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}\) do.

Step 3: With \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) fully faithful, the defining property of Serre functors gives a canonical map of functors \(\mathsf {S}^{-1}\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\mathsf {S}\rightarrow \mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) which can be spelled out in the following diagram:

It is easy to check that the left-hand vertical arrow is an isomorphism whenever we plug in objects from \(\Omega \): both vector spaces are zero for objects from \(\mathsf {E}^\perp \); for the top row, use \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_i,\mathsf {S}(-)) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\mathsf {S}^{-1}(E_i),-) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\Sigma ^{-k_{i-1}}E_{i-1},-)\). For objects \(E_i\), again use \(\mathsf {S}(E_i)\cong \Sigma ^{k_i}E_{i+1}\). Hence \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) commutes with the Serre functor on \(\Omega \), and so by more general theory is essentially surjective; see [27, Corollary 1.56], this is the place where we need the assumption that \(\mathsf D\) is indecomposable.\(\square \)

Remark 4.6

We point out that the twist \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) defined above is an instance of a spherical functor [3], given by the following data:

where \(\mathsf {D}^b({\mathbf {k}}^n)=\bigoplus _n\mathsf {D}^b({\mathbf {k}})\) is a decomposable category. It is easy to see that R is right adjoint to S and that \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) coincides with the cone of the adjunction morphism \(SR\rightarrow {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\).

An object \(X\in \mathsf D\) is called d-spherelike if \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X,X) = {\mathbf {k}}\oplus \Sigma ^{-d}{\mathbf {k}}\); see [22] and also Sect. 6.3. We will now show that reasonable exceptional cycles come with a spherelike object. For this purpose, we call an exceptional cycle \(E_* = (E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) irredundant if \(E_n\notin \mathsf {thick}_{}(E_1,\ldots ,E_{n-1})\). Recall that an exceptional n-cycle \((E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) comes with a tuple of integers \((k_1,\ldots ,k_n)\) and that we have set \(k = k_1+\cdots +k_n\).

Proposition 4.7

Let \(E_* = (E_1,\ldots ,E_n)\) be an irredundant exceptional n-cycle in \(\mathsf D\). Then there exists a \((k+1-n)\)-spherelike object \(X\in \mathsf D\) with non-zero maps \(X\rightarrow E_1\) and \(\Sigma ^{n-1-k+k_n}E_n\rightarrow X\).

Proof

Inductively, we construct a series of objects \(X_1,\ldots ,X_n\) with the following properties for \(i<n\):

-

(i)

\(X_i\) is exceptional,

-

(ii)

\(X_i \in \mathsf {thick}_{}(E_1,\ldots ,E_i)\),

-

(iii)

\({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_i,E_{i+1}) = \Sigma ^{-l_i}{\mathbf {k}}\) with \(l_i {:}{=}k_1+\cdots +k_i + 1-i\).

These conditions are satisfied for \(X_1{:}{=}E_1\), because \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_1,E_2)\) is generated by \(\alpha _1: E_1\rightarrow \Sigma ^{k_1}E_2\). Assume \(X_i\) with \(i < n-1\) has already been constructed. By (iii) there is a unique object \(X_{i+1}\) with a non-split distinguished triangle

Moreover, \((X_i,E_{i+1})\) is an exceptional sequence with just one (graded) morphism by (ii) and (iii). So in the above triangle, the object \(X_{i+1}\) is, up to suspension, the left mutation of that pair. In particular, \(X_{i+1}\) is exceptional. By construction, \(X_{i+1}\) satisfies (ii).

Since \(i+1<n\), \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_i,E_{i+2})=0\) by (ii) and the definition of exceptional cycles, hence \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_{i+1},E_{i+2}) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\Sigma ^{l_i-1}E_{i+1},E_{i+2})\). As \(\alpha _{i+1}: E_{i+1}\rightarrow \Sigma ^{k_{i+1}}E_{i+2}\) generates \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_{i+1},E_{i+2})\), we find that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_{i+1},E_{i+2})\) is 1-dimensional, and situated in degree \(l_i+k_{i+1} - 1 = l_{i+1}\).

Having constructed \(X_{n-1}\) in this fashion, we can use (iii) to define

This triangle induces a commutative diagram of complexes of \({\mathbf {k}}\)-vector spaces

and we know that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_{n-1}, X_{n-1}) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n,\Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n) = {\mathbf {k}}\), since \(X_{n-1}\) and \(E_n\) are exceptional. Moreover, we get \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_{n-1}, \Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n) = {\mathbf {k}}\) from applying \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (-,E_n)\) to the triangle defining \(X_{n-1}\) and using \(X_{n-2}\in {\langle E_1,,\ldots ,E_{n-2}\rangle }\), none of which map to \(E_n\). In particular, the map f sends the identity to the morphism \(X_{n-1} \rightarrow \Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n\) defining \(X_n\). Hence f is an isomorphism, thus \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_n, \Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n) = 0\) and we arrive at the isomorphism  .

.

We turn to \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (\Sigma ^{l_{n-1}}E_n, X_{n-1})\). By (ii) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_n,E_i)=0\) for \(1<i<n\),

where \(k = k_1 + \cdots +\, k_n\) as before. Now g is a map of two 1-dimensional complexes. This map cannot be an isomorphism, because this would force \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X_n,X_n)=0\), hence \(X_n=0\), which implies \(X_{n-1} \cong \Sigma ^{l_{n-1}} E_n\). But we have \(X_{n-1}\in \mathsf {thick}_{}(E_1,\ldots ,E_{n-1})\) by (ii) and also \(E_n\notin \mathsf {thick}_{}(E_1,\ldots ,E_{n-1})\) as \(E_*\) is irredundant; which gives a contradiction. Therefore we find that \(g=0\) and thus,

Hence \(X{:}{=}X_n\) is indeed \((k+1-n)\)-spherelike. The degrees of non-zero maps in \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_n,X)\) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X,E_1)\) are computed with the same methods as above.\(\square \)

Example 4.8

The additional hypothesis on \(E_*\) is necessary: consider \(\mathsf {D}= \mathsf {D}^b({\mathbf {k}}A_3)\) for the \(A_3\)-quiver \(1\rightarrow 2\rightarrow 3\). Denoting the injective-projective module by \(M=P(1)=I(3)\), the sequence \(E_*=(S(1),S(2),S(3),M)\) is an exceptional cycle with \(k_*=(1,1,0,0)\). The cycle is redundant because \(M\in \mathsf {thick}_{}(S(1),S(2),S(3))\); note that (S(1), S(2), S(3)) is a full exceptional collection for \(\mathsf {D}\).

Following the iterative construction of the above proof, we get \(X_1 = S(1)\), \(X_2=I(2)\) and \(X_3=M\). This forces \(X=X_4=0\), and we do not get a spherelike object in this case. Note that \(E_*\) still gives a twist autoequivalence, which for this example is just \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}=\tau ^{-1}\) on objects. In light of this example, it would also be interesting to investigate twists coming from redundant exceptional cycles further.

5 Autoequivalence groups of discrete derived categories

We now use the general machinery of the previous section to show that categories \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) possess two very interesting and useful autoequivalences. We will denote these by \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) and prove some crucial properties: they commute with each other, act transitively on the indecomposables of each \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) component and provide a weak factorisation of the Auslander–Reiten translation: \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}= \tau ^{-1}\) on objects. Moreover, \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) acts trivially on \(\mathcal {Y}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) acts trivially on \(\mathcal {X}\); see Proposition 5.4 and Corollary 5.5 for the precise assertions. We then give an explicit description of the group of autoequivalences of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) in Theorem 5.7.

The category \(\mathsf D= \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) with \(n>r\) is Hom-finite, indecomposable, algebraic and has Serre duality (see Appendix A.1). Therefore we can apply the results of the previous section to \(\mathsf D\).

Our first observation is that every sequence of \(m+r\) consecutive objects at the mouth of \(\mathcal {X}^0\) is an exceptional \((m+r)\)-cycle; likewise, every sequence of \(n-r\) consecutive objects at the mouth of \(\mathcal {Y}^0\) is an exceptional \((n-r)\)-cycle, by which we mean a \((r+1)\)-spherical object in case \(n-r=1\). For the moment, we specify two concrete sequences:

Lemma 5.1

\(E_*\) forms an exceptional \((m+r)\)-cycle in \(\mathsf D\) with \(k_*=(1,\ldots ,1,1-r)\), and \(F_*\) forms an exceptional \((n-r)\)-cycle in \(\mathsf D\) with \(k_*=(1,\ldots ,1,1+r)\).

Proof

The object \(X^0_{11}\) is exceptional by Lemma 3.1, hence any object at the mouth \(X^0_{ii}=\tau ^{1-i}(X^0_{11})\) is. This point also gives the second condition of exceptional cycles: for \(i=1,\ldots ,m+r-1\), we have \(\mathsf {S}E_i = \Sigma \tau X^0_{m+r+1-i,m+r+1-i} = \Sigma X^0_{m+r-i,m+r-i} = \Sigma E_{i+1}\) and at the boundary step we have \(\mathsf {S}E_{m+r} = \Sigma \tau X^0_{11} = \Sigma X^0_{00} = \Sigma ^{1-r} X^0_{m+r,m+r} = \Sigma ^{1-r} E_1\), where we freely make use of the results stated in Sect. 2. Hence the degree shifts of the sequence \(E_*\) are \(k_1=\ldots =k_{m+r-1}=1\) and \(k_{m+r}=1-r\). Finally, the required vanishing \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(E_i,E_j)=0\) unless \(j=i+1\) or \(i=j\) again follows from Lemma 3.1.

The same reasoning works for \(\mathcal {Y}\), now with the boundary step degree computation \(\mathsf {S}F_{n-r} = \Sigma \tau Y^0_{11} = \Sigma Y^0_{00} = \Sigma ^{1+r} Y^0_{n-r,n-r} = \Sigma ^{1+r} F_1\). \(\square \)

The next lemma shows that the functors \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}\) and \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{F_*}\) of the last section take on a particularly simple form, where we use the notation \({}_0X,X_0,{}^0Y,Y^0\) from Sects. 3.2, 3.3:

Lemma 5.2

For \(X\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X})\) and \(Y\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Y})\),

Proof

This follows immediately from the definition of these functors in Sect. 4, Proposition 3.4 and Properties 1.2(3), i.e. \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {X}= \tau ^{-m-r}\) and \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {Y}= \tau ^{n-r}\) on objects.

Note that the right-hand sides extend to direct sums. Another description of \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}(X)\) is as the minimal approximation of X with respect to the mouth of \(\mathcal {X}^0\), and analogously for \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{F_*}\).\(\square \)

The actual choice of exceptional cycle is not relevant as the following easy lemma shows. We only state it for \(E_*\) but the analogous statement holds for \(F_*\), with the same proof. This allows us to write \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) instead of \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) instead of \(\mathsf {T}\!_{F_*}\).

Lemma 5.3

Any two exceptional cycles \(E_*, E'_*\) at the mouths of \(\mathcal {X}\) components differ by suspensions and AR translations, and the associated twist functors coincide: \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*} = \mathsf {T}\!_{E'_*}\).

Proof

A suitable iterated suspension will move \(E'_*\) into the \(\mathcal {X}\) component that \(E_*\) inhabits, and two exceptional cycles at the mouth of the same AR component obviously differ by some power of the AR translation. Thus we can write \(E'_* = \Sigma ^a\tau ^b E_*\) for some \(a,b\in {\mathbb {Z}}\). We point out that the suspension and the AR translation commute with all autoequivalences (it is a general and easy fact that the Serre functor does, see [27, Lemma 1.30]). Finally, we have \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E'_*} = \mathsf {T}\!_{\Sigma ^a\tau ^bE_*} = \Sigma ^a\tau ^b\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\Sigma ^{-a}\tau ^{-b} = \mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\), using Lemma 4.1.\(\square \)

Proposition 5.4

The twist functors \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) act as follows on objects of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\), where \(X\in \mathcal {X}, Y\in \mathcal {Y}\) and \(k=0,\ldots ,r-1\) and \(i,j\in {\mathbb {Z}}\):

Corollary 5.5

The twist functors \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) act simply transitively on each component \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) and factorise the inverse AR translation: \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}= \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}= \tau ^{-1}\) on the objects of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\). Moreover, \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\), \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\) and \(\Sigma \) act transitively on \(\mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\).

Proof of the proposition

By Lemma 3.1, we have \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X^k_{ii},Y)=0\) for all \(Y\in \mathcal {Y}\). This immediately implies \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}|_\mathcal {Y}= {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\).

Action of \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) on objects of \(\mathcal {X}\): we recall that the proof of Theorem 4.5 showed \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}(E_i)=\Sigma ^{1-k_{i-1}}(E_{i-1})\), and furthermore \(k_1=\cdots =k_{m+r-1}=1\) and \(k_{m+r}=1-r\) from Lemma 5.1. Hence \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}(E_i)=\tau ^{-1}(E_i)\) for all i—as explained in Lemma 5.3, this holds for any exceptional cycle at an \(\mathcal {X}\) mouth. Since \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) is an equivalence and each \(\mathcal {X}\) component is of type \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \), this forces \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}|_{\mathcal {X}}=\tau ^{-1}\) on objects.

Action of \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\) on objects of \(\mathcal {Z}\): Pick \(Z^0_{ij}\in \mathcal {Z}^0\) with \(1\le i\le m+r\). Using \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}= \mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}\) with the cycle originally specified, i.e. \(E_{m+r}=X^0_{11}\), we invoke Lemma 3.1 once more to get \({\mathbf {k}}= {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (X^0_{ii},Z^0_{ij}) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_{m+r+1-i},Z^0_{ij})\), and \(0 = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (E_l,Z^0_{ij})\) for all \(l\ne m+r+1-i\). So \(\mathsf {F}\!\!\,_{E_*}(Z^0_{ij}) = X^0_{ii}\) and the triangle defining \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(Z^0_{ij})\) is one of the special triangles of Properties 1.2(4):

Application of AR translations extends this computation to arbitary \(Z\in \mathcal {Z}^0\), and suspending extends it to all \(\mathcal {Z}\) components, thus \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}(Z^0_{i,j}) = Z^0_{i+1,j}\).

Remaining cases: Analogous reasoning shows \(\mathsf {T}\!_{F_*}(F_i)=\tau ^{-1}(F_i)\) for all \(i=1,\ldots ,n-r\), and the rest of the above proof works as well: \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}(Z^0_{i,j})=Z^0_{i,j+1}\), now using the other special triangle. \(\square \)

The following technical lemma about the additive closures of the \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathcal {Y}\) components will be used later on, but is also interesting in its own right. Using the twist functors, the proof is easy.

Lemma 5.6

Each of \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(\mathcal {Y}\) is a thick triangulated subcategory of \(\mathsf D\).

Proof

The proof of Proposition 5.4 contains the fact \(\mathsf {thick}_{}(E_*)^\perp = \mathcal {Y}\). Perpendicular subcategories are always closed under extensions and direct summands; since \(\mathsf {thick}_{}(E_*)\) is by construction a triangulated subcategory, the orthogonal complement \(\mathcal {Y}\) is triangulated as well.\(\square \)

Our results enable us to compute the group of autoequivalences of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\). For \(\Lambda (1,2,0)\), König and Yang [33, Lemma 9.3] showed \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (1,2,0))) \cong {\mathbb {Z}}^2 \times {\mathbf {k}}^*\).

Theorem 5.7

The group of autoequivalences of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) is an abelian group generated by \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}\), \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}\), \(\Sigma \) and \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda (r,n,m))={\mathbf {k}}^*\), subject to one relation

As an abstract group, \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))) \cong {\mathbb {Z}}^2 \times {\mathbb {Z}}/\ell \times {\mathbf {k}}^*\), where \(\ell {:}{=}\gcd (r,n,m)\).

Proof

In this proof, we will write \(\mathsf {D}= \mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) and \(\Lambda = \Lambda (r,n,m)\).

Step 1: \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda ) = {\mathbf {k}}^*\) from common scaling of arrows.

Recall that units \(u\in \Lambda \) induce inner automorphisms \(c_u(\alpha )=u\alpha u^{-1}\), and thus a normal subgroup \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Inn}}}}(\Lambda )\subseteq {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\Lambda )\). It is a well-known fact that inner automorphisms induce autoequivalences of \(\mathsf {mod}(\Lambda )\) and \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\) which are isomorphic to the identity; see [46, §3]. The quotient group \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda ) = {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\Lambda )/{{\mathrm{\mathsf {Inn}}}}(\Lambda )\) acts faithfully on modules. The form of the quiver and the relations for \(\Lambda (r,n,m)\) imply that algebra automorphisms can only act by scaling arrows.

Scaling of arrows leads to a subgroup \(({\mathbf {k}}^*)^{m+n}\) of \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\Lambda )\). However, choosing an indecomposable idempotent e (i.e. a vertex) together with a scalar \(\lambda \in {\mathbf {k}}^*\) produces a unit \(u = 1_\Lambda + (\lambda -1)e\), and hence an inner automorphism \(c_u\in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\Lambda )\). It is easy to check that \(c_u(\alpha )=\frac{1}{\lambda }\alpha \) if \(\alpha \) ends at e, and \(c_u(\alpha )=\lambda \alpha \) if \(\alpha \) starts at e, and \(c_u(\alpha )=\alpha \) otherwise. Since the quiver of \(\Lambda \) has one cycle, we see that an \((n+m-1)\)-subtorus of the subgroup \(({\mathbf {k}}^*)^{m+n}\) of arrow-scaling automorphisms consists of inner automorphisms. Furthermore, the automorphism scaling all arrows simultaneously by the same number is easily seen not to be inner, hence, \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )={\mathbf {k}}^*\). Note that the class of an automorphism scaling precisely one arrow also generates \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\).

Step 2: \(\varphi \in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})\) is isomorphic to the identity on objects \(\Longleftrightarrow \) \(\varphi \in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\).

By Step 1, it is clear that algebra automorphisms act trivially on objects. Let now \(\varphi \in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})\) fixing all objects. In particular, \(\varphi \) fixes the abelian category \(\mathsf {mod}(\Lambda )\) and the object \(\Lambda \), thus giving rise to \(\varphi : \Lambda \rightarrow \Lambda \), i.e. an automorphism which by Step 1 can be taken to be outer.

Step 3: The subgroup \({\langle \Sigma ,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X},\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y},{{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\rangle }\) is abelian.

The suspension commutes with all exact functors. Next, to see \([\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X},\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}]={{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\), we fix exceptional cycles \(E_*\) for \(\mathcal {X}\) and \(F_*\) for \(\mathcal {Y}\); then \(\mathsf {T}\!_{E*}\mathsf {T}\!_{F_*}(\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*})^{-1}= \mathsf {T}\!_{\mathsf {T}\!_{E_*}(F_*)} = \mathsf {T}\!_{F_*}\) by Lemma 4.1 and Proposition 5.4. Let \(f\in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\). Then we have \([f,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}]=[f,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}]={{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) by the same lemma, now using \(f(E_*)=E_*\) and \(f(F_*)=F_*\) from Step 2.

Step 4: \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})\) is generated by \(\Sigma ,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X},\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y},{{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\).

Fix a \(Z\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\). For any \(\varphi \in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})\), there are \(a,b,c\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) with \(\Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,c}(Z) = \varphi (Z)\), since the suspension and the twist functors act transitively on \(\mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\) by Corollary 5.5. Therefore, \(\psi {:}{=}\Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,c}\varphi ^{-1}\) fixes Z. Moreover, since all autoequivalences commute with \(\tau \) (because they commute with the Serre functor \(\mathsf {S}= \Sigma \tau \) and with \(\Sigma \)) and \(\mathcal {Z}\) is a \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty ^\infty \)-component, either \(\psi \) is the identity on \(\mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\) or else \(\psi \) flips \(\mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\) along the \(Z\tau (Z)\) axis. However, the latter possibility is excluded by the action of \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {Z}\); see Properties 1.2(3).

By Properties 1.2(4), every indecomposable object of \(\mathcal {X}\) or \(\mathcal {Y}\) is a cone of a morphism \(Z_1\rightarrow Z_2\) for some \(Z_1,Z_2\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {Z})\). Moreover, the morphism \(Z_1\rightarrow Z_2\) is unique up to scalars by Theorem 6.1. (The proofs in that section make no use of the autoequivalence group. Note that by the proof of Theorem 6.1, morphism spaces between indecomposable objects in \(\mathcal {Z}\) are 1-dimensional, even for \(r=1\).) Hence \(\varphi \) actually fixes all indecomposable objects and thus all objects of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda )\).

Thus, by Step 2, \(\psi \in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\) and \(\varphi \in {\langle \Sigma ,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X},\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y},{{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\rangle }\).

Step 5: \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})\) is abelian with one relation \(f_0 \Sigma ^{-r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,m+r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,r-n}={{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) for some \(f_0\in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\).

By Steps 3 and 4, \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D})={\langle \Sigma ,\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X},\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y},{{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\rangle }\) is abelian. Properties 1.2(3) and Proposition 5.4 imply that the autoequivalence \(\Sigma ^{-r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,m+r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,r-n}\) fixes all objects of \(\mathsf {D}\), hence \(f_0\Sigma ^{-r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,m+r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,r-n} = {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) for a unique automorphism \(f_0\in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\).

Let now \(a,b,c\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) and \(g\in {{\mathrm{\mathsf {Out}}}}(\Lambda )\) such that \(g \Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,c} = {{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\). In particular, \(\psi {:}{=}\, \Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,c}\) fixes all objects. From \(X=\psi (X)=\Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}(X)=\Sigma ^a\tau ^{-b}(X)\) we deduce first \(a=lr\) for some \(l\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) and then \(b=-l(m+r)\); whereas \(Y=\psi (Y)\) similarly implies \(a=kr\) and \(c=k(n-r)\) for some \(k\in {\mathbb {Z}}\). Hence \(k=l\) and \(\psi = \Sigma ^{lr}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,-l(m+r)}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,l(n-r)}=f_0^{l}\). So \(g=f_0^{-l}\) and altogether, \( g\Sigma ^a\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,b}\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,c} = (f_0 \Sigma ^{-r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,m+r} \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,n-r})^{-l}\) is a power of the stated relation.

Step 6: \({{\mathrm{\mathsf {Aut}}}}(\mathsf {D}) \cong {\mathbb {Z}}^2 \times {\mathbb {Z}}/(r,n,m) \times {\mathbf {k}}^*\).

This is elementary algebra: let A be a free abelian group of finite rank and \(a_0\in A\), \(f_0\in {\mathbf {k}}^*\). Write \(a_0=da_1\) with \(d\in {\mathbb {Z}}\) and \(a_1\) indivisible. Choose \(f_1\in {\mathbf {k}}^*\) with \(f_1^d=f_0\)—this is possible because \({\mathbf {k}}\) is algebraicaly closed. Now fix a group homomorphism \(\nu : A\rightarrow {\mathbb {Z}}\) with \(\nu (a_1)=1\)—this is possible because \(a_1\) is indivisible. Consider the diagram with exact rows

where \(\alpha (na_0,1) = (na_0,f_0^n)\) and \(\beta (a,f) = (a,ff_1^{\nu (a)})\). Both maps are easily checked to be group homomorphisms and bijective. Moreover, the left-hand square commutes:

Therefore we obtain an induced isomorphism between the right-hand quotients:

For the case at hand, \(A={\mathbb {Z}}^3\) and \(a_0=(r,n,m)\in {\mathbb {Z}}^3\) and hence \(A/a_0\cong {\mathbb {Z}}^2\times {\mathbb {Z}}/\ell \) with the greatest common divisor \(\ell =(r,n,m)\), by the theory of elementary divisors.\(\square \)

Question

It is natural to speculate about the action of the various functors on maps. More precisely, we ask whether

-

(1)

\(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {X}= \tau ^{-m-r}\) and \(\Sigma ^r|_\mathcal {Y}= \tau ^{n-r}\)

-

(2)

\(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}|_\mathcal {X}= \tau ^{-1}\) and \(\mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}|_\mathcal {Y}= \tau ^{-1}\)

-

(3)

\(\Sigma ^{r} = \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {X}^{\,m+r} \, \mathsf {T}\!_\mathcal {Y}^{\,r-n}\)

hold as functors. In all cases, we know these relations hold on objects. Note that (1) and (2) together imply (3), and that (3) means \(f_0={{\mathrm{{\mathsf {id}}}}}\) in Theorem 5.7.

6 Hom spaces: dimension bounds and graded structure

In this section, we prove a strong result about \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda ){:}{=}\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) which says that the dimensions of homomorphism spaces between indecomposable objects have a common bound. We also present the endomorphism complexes in Lemma 6.3.

6.1 Hom space dimension bounds

The bounds are given in the the following theorem; for more precise information in case \(r=1\) see Proposition 6.2.

Theorem 6.1

Let A, B be indecomposable objects of \(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m))\) where \(n>r\). If \(r\ge 2\), then \(\dim {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \le 1\) and if \(r=1\), then \(\dim {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B) \le 2\).

Proof

Our strategy for establishing the dimension bound follows that of the proofs of the Hom-hammocks. Let \(A,B\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathsf {D}^b(\Lambda (r,n,m)))\) and assume \(r>1\). In this proof, we use the abbreviation \(\hom = \dim {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}\). We want to show \(\hom (A,B)\le 1\) by considering the various components separately.

Case \(A\in \mathcal {X}^k\) or \(\mathcal {Y}^k\): Consider first \(A,B\in \mathcal {X}^k\) and perform induction on the height of A. If \(A=A_0\) sits at the mouth, then \(\hom (A,B)\le 1\) by Lemma 3.1. For A higher up, and assuming \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(A,B)\ne 0\), which means \(B\in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{AA_0})\), we consider one of the triangles from Lemma 3.2

Using the Hom-hammock Proposition 3.4, we see that \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet (A'',B)=0\) if \(B\in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A)\) and \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}^\bullet ({}_0 A,B)=0\) otherwise. Thus the exact sequence

yields \(\hom (A,B) \le \hom (A'',B)\) if \(B\in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A)\) and \(\hom (A,B) \le \hom ({}_0 A,B)\) otherwise. The induction hypothesis then gives \(\hom (A,B)\le 1\).

The subcase \(B\in \mathcal {X}^{k+1}\) follows from the above by Serre duality.

Furthermore, the above argument applies without change to \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^k\)—with \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(A)\subset \mathcal {Z}^k\) understood to mean the subset of indecomposables of \(\mathcal {Z}^k\) admitting non-zero morphisms from A (these form a ray in \(\mathcal {Z}^k\)) and similarly \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(B)\subset \mathcal {X}^k\), and application of Proposition 3.6. An obvious modification, which we leave to the reader, extends the argument to \(B\in \mathcal {Z}^{k+1}\). The statements for \(A\in \mathcal {Y}\) are completely analogous.

Case \(A\in \mathcal {Z}^k\): In light of Serre duality, we don’t need to deal with \(B \in \mathcal {X}\) or \(B \in \mathcal {Y}\). Therefore we turn to \(B\in \mathcal {Z}\). However, we already know from the proof of Proposition 3.6 that the dimensions in the two non-vanishing regions \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(A))\) and \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\mathsf {S}A))\) are constant. Since the \(\mathcal {Z}\) components contain the simple S(0) and the twist functors together with the suspension act transitively on \(\mathcal {Z}\), it is clear that \(\hom (A,A)=\hom (A,\mathsf {S}A)^*=1\). This completes the proof.\(\square \)

Proposition 6.2

Let \(r=1\) and \(X,A\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X})\). Then

The following diagram illustrates the proposition: all indecomposables A in the heavily shaded square have \(\dim {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,A)=2\):

Proof

The argument is similar to the computation of the Hom-hammocks in the \(\mathcal {Z}\) components from Sect. 3. We proceed in several steps.

Step 1: For any \(A\in \mathsf {ind}(\mathcal {X})\) of height 0 the claim follows from Lemma 3.1. Otherwise we consider the AR mesh which has A at the top, and let \(A'\) and \(A''\) be the two indecomposables of height \(h(A)-1\). There are two triangles (see Lemma 3.2):

where, as before, \({}_0A\) and \(A_0\) are the unique indecomposable objects on the mouth which are contained in respectively \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! -}(A)\) and \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! +}(A)\). Applying the functor \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,-)\) to both triangles we obtain two exact sequences:

Since \({}_0A\) and \(A_0\) lie on the mouth of the component, Lemma 3.1 implies that the outer terms have dimension at most 2. Using the fact that \(X_0\) and \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X\) are the only objects of the Hom-hammock from X lying on the mouth, Lemma 3.1 actually yields:

The spaces are 2-dimensional precisely when A belongs to the intersections of the (co)rays on the right-hand side, which can only happen when \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X = X_0\). The set of rays and corays listed above divide the component into regions. In this proof, each region is considered to be closed below and open above.

Step 2: The function \(\hom (X,-)\) is constant on each region, and changes by at most 1 when crossing a (co)ray if \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X \ne X_0\), and by at most 2 otherwise.

The first claim is clear from exact sequences (3) and (4). We show the second claim for rays; for corays the argument is similar. We get \(\hom (X,A) \le \hom (X,A'')+ \hom (X, {}_0 A)\) from sequence (3). This yields the stated upper bound for \(\hom (X,A) \), as \(\hom (X, {}_0 A) \le 1\) when \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X \ne X_0\) and \(\hom (X, {}_0 A) \le 2\) otherwise. For the lower bound, instead observe that \(\hom (X,A'')\le \hom (X,\Sigma {}_0 A) +\hom (X,A)\), again from sequence (3).

Step 3: \(\psi =0\) unless \(A \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} \,{}_0 \mathsf {S}X)\) and \(\mu =0\) unless \(A \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\Sigma X_0)\).

If \(A \notin \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} \, X_0) \cup \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} \,{}_0 \mathsf {S}X)\) then \(\hom (X,\Sigma {}_0 A)=0\) and so \(\psi =0\) trivially. Therefore, we just need to consider \(A \in \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} \, X_0)\) but \(A\notin \mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} \,{}_0 \mathsf {S}X)\), and in this case \(\hom (X,\Sigma \, {}_0A)=1\). It is clear that the maps going down the coray from X to \(X_0\) span a 1-dimensional subspace of \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,\Sigma \, {}_0A)\), which therefore is the whole space. Using properties of the \({\mathbb {Z}}A_\infty \) mesh, the composition of such maps with a map along \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(X_0)\) from \(X_0\) to \(\Sigma A\) defines a non-zero element in \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,\Sigma \, A)\). Thus the map \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,\Sigma {}_0 A) \rightarrow {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X, \Sigma A)\) in the sequence (3) is injective and it follows that \(\psi =0\). The proof of the second statement is similar: here we use the chain of morphisms in Properties 1.2(5) to show that the map \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,\Sigma ^{-1} A) \rightarrow {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X, \Sigma ^{-1} A_0)\) in the sequence (4) is surjective.

Step 4: If \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1} X_0)\) (or \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\Sigma {}_0 \mathsf {S}X)\), respectively) does not coincide with one of the other three (co)rays, then crossing it does not affect the value of \(\hom (X,-)\).

Suppose \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1}\, X_0) \ni A\) doesn’t coincide with \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(X_0)\), \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}({}_0\mathsf {S}X)\) or \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\Sigma ^{-1}{}_0\mathsf {S}X)\). Thus \(\hom (X,{}_0A)=0\), and from Step 3 the map \(\psi =0\), hence \({{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,A) = {{\mathrm{\mathrm {Hom}}}}(X,A'')\). Similarly, suppose \(A \in \mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\Sigma \,{}_0 \mathsf {S}X)\) and this doesn’t coincide with any of the other corays. Then \(\hom (X,A_0)=0\) and \(\mu =0\) and again the claim follows.

Step 5: There are three possible configurations of rays and corays determining the regions where \(\hom (X, -)\) is constant.

It follows from Step 4 that it suffices to consider the remaining rays and corays,

for determining the regional constants \(\hom (X, -)\). Note that these are precisely the rays and corays required to bound the regions \(\mathsf {ray}_{\! +}(\overline{XX_0})\) and \(\mathsf {coray}_{\! -}(\overline{{}_0(\mathsf {S}X),\mathsf {S}X})\) of the statement of the proposition. Considering their relative positions on the mouth, \(\Sigma ^{-1} \,{}_0 \mathsf {S}X\) is always furthest to the left and \(\Sigma X_0\) is furthest to the right, while \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X\) can lie to the left, or to the right, or coincide with \(X_0\), depending on the height of X. We consider now the case where \({}_0 \mathsf {S}X\) is to the left of \(X_0\). We label the regions in the following diagram by letters A–M (this is the order in which we treat them, and the subscripts indicate the claimed \(\hom (X,-)\) for the region):

First we note that regions A–E all contain part of the mouth and so \(\hom (X,-)=0\) here. Looking at the maps from X that exist in the AR component we see that \(\hom (X,-) \ge 1\) on regions H, I, K and L; and on F, G, J and K using Serre duality. However regions F–I are reached by crossing a single ray or coray from one of the regions A–E. By Step 2 we thus get \(\hom (X,-) = 1\) on regions F–I.