Abstract

Summary

Population-based screening for osteoporosis is still controversial and has not been implemented. Non-participation in systematic screening was evaluated in 34,229 women age 65–81 years. Although participation rate was high, non-participation was associated with comorbidity, aging other risk factors for fractures, and markers of low social status, e.g., low income, pension, and living alone. A range of strategies is needed to increase participation, including development of targeted information and further research to better understand the barriers and enablers in screening for osteoporosis.

Introduction

Participation is crucial to the success of a screening program. The objective of this study was to analyze non-participation in Risk-stratified Osteoporosis Strategy Evaluation, a two-step population-based screening program for osteoporosis.

Methods

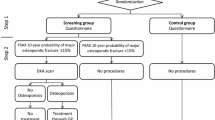

Thirty-four thousand two hundred twenty-nine women aged 65 to 81 years were randomly selected from the background population and randomized to either a screening group (intervention) or a control group. All women received a self-administered questionnaire designed to allow calculation of future risk of fracture based on FRAX. In the intervention group, women with an estimated high risk of future fracture were invited to DXA scanning. Information on individual socioeconomic status and comorbidity was obtained from national registers.

Results

A completed questionnaire was returned by 20,905 (61%) women. Non-completion was associated with older age, living alone, lower education, lower income, and higher comorbidity. In the intervention group, ticking “not interested in DXA” in the questionnaire was associated with older age, living alone, and low self-perceived fracture risk. Women with previous fracture or history of parental hip fracture were more likely to accept screening by DXA. Dropping out when offered DXA, was associated with older age, current smoking, higher alcohol consumption, and physical impairment.

Conclusions

Barriers to population-based screening for osteoporosis appear to be both psychosocial and physical in nature. Women who decline are older, have lower self-perceived fracture risk, and more often live alone compared to women who accept the program. Dropping out after primary acceptance is associated not only with aging and physical impairment but also with current smoking and alcohol consumption. Measures to increase program participation could include targeted information and reducing physical barriers for attending screening procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY (2013) European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:23–57

Johnell O, Kanis J (2005) Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 16(Suppl 2):S3–S7

Borgstrom F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, Lidgren L, Ponzer S, Svensson O, Abdon P, Ornstein E, Lunsjo K, Thorngren KG, Sernbo I, Rehnberg C, Jonsson B (2006) Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int 17:637–650

Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733

Strom O, Borgstrom F, Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B (2011) Osteoporosis: burden, health care provision and opportunities in the EU: a report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA). Arch Osteoporos 6:59–155

Black DM, Rosen CJ (2016) Clinical Practice. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 374:254–262

Lidgren L (2012) Looking back at the start of the bone and joint decade what have we learnt? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 26:169–171

Kanis JA, Delmas P, Burckhardt P, Cooper C, Torgerson D (1997) Guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. The European Foundation for Osteoporosis and Bone Disease. Osteoporos Int 7:390–406

Nelson HD, Haney EM, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Chou R (2010) Screening for osteoporosis: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 153:99–111

Rejnmark L, Abrahamsen B, Ejersted L, Beck Jensen J-E, Madsen OR, Mosekilde L, Schwarz P, Vestergaard P, Langdahl B (2012) Vejledning til udredning og behandling af osteoporose. www.dkms.dk/PDF/DKMS_Osteoporose_2009.pdf

NICE Guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg146. Accessed 6 July 2017

NICE PARTWAY. https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/osteoporosis. Accessed 20 Marts 2017

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24:2135–2152

Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L (2005) Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int 16:134–141

van Dam L, Korfage IJ, Kuipers EJ, Hol L, van Roon AH, Reijerink JC, van Ballegooijen M, van Leerdam ME (2013) What influences the decision to participate in colorectal cancer screening with faecal occult blood testing and sigmoidoscopy? Eur J Cancer 49:2321–2330

Strech D (2014) Participation rate or informed choice? Rethinking the European key performance indicators for mammography screening. Health Policy 115(1):100–103

Rothmann MJ, Huniche L, Ammentorp J, Brakmann R, Glüer CC, Hermann AP (2014) Women’s perspectives and experiences on screening for osteoporosis (Risk-stratified Osteoporosis Strategy Evaluation, ROSE). Arch Osteoporos 9:192

McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Lock S, McCrink L, Adekunle F, Roberts D (2011) Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int 22:2083–2098

Rubin KH, Holmberg T, Rothmann MJ, Hoiberg M, Barkmann R, Gram J, Hermann AP, Bech M, Rasmussen O, Gluer CC, Brixen K (2015) The risk-stratified osteoporosis strategy evaluation study (ROSE): a randomized prospective population-based study. Design and baseline characteristics. Calcif Tissue Int 96:167–179

Rubin KH, Abrahamsen B, Hermann AP, Bech M, Gram J, Brixen K (2011) Fracture risk assessed by Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) compared with fracture risk derived from population fracture rates. Scand J Public Health 39:312–318

FRAX WHO Frakture Risk Assessment Tool. www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp. Accessed 21 Marts 2017

Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jorgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen JH (1999) The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 46:263–268

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 39:30–33

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CRA (1987) New method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383

Statistics Denmark. http://www.dst.dk/en/tilSalg/Forskningsservice. Accessed Marts 2017

Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW (2011) Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health 39:91–94

Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J (2011) Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health 39:103–105

Pedersen CB (2011) The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 39:22–25

Jensen LF, Pedersen AF, Andersen B, Vedsted P (2012) Identifying specific non-attending groups in breast cancer screening—population-based registry study of participation and socio-demography. BMC Cancer 12:518

Frederiksen BL, Jorgensen T, Brasso K, Holten I, Osler M (2010) Socioeconomic position and participation in colorectal cancer screening. Br J Cancer 103:1496–1501

Davisson L, Warden M, Manivannan S, Kolar M, Kincaid C, Bashir S, Layne R (2009) Osteoporosis screening: factors associated with bone mineral density testing of older women. J Women's Health (Larchmt) 18:989–994

McNally DN, Kenny AM, Smith JA (2007) Adherence of academic geriatric practitioners to osteoporosis screening guidelines. Osteoporos Int 18:177–183

Barr RJ, Stewart A, Torgerson DJ, Seymour DG, Reid DM (2005) Screening elderly women for risk of future fractures—participation rates and impact on incidence of falls and fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 76:243–248

Rubin KH, Abrahamsen B, Hermann AP, Bech M, Gram J, Brixen K (2011) Prevalence of risk factors for fractures and use of DXA scanning in Danish women. A regional population-based study. Osteoporos Int 22:1401–1409

Hoiberg MP, Rubin KH, Gram J, Hermann AP, Brixen K, Haugeberg G (2015) Risk factors for osteoporosis and factors related to the use of DXA in Norway. Arch Osteoporos 10:16

Siris ES, Brenneman SK, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Sajjan S, Berger ML, Chen YT (2006) The effect of age and bone mineral density on the absolute, excess, and relative risk of fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50-99: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment (NORA). Osteoporos Int 17:565–574

NOGG. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women from the age of 50 years in UK. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/NOGG/NOGG_Pocket_Guide_for_Healthcare_Professionals.pdf. Accessed 21 Marts 2017

Walker-Bone K (2012) Recognizing and treating secondary osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 8:480–492

Demeter S, Leslie WD, Lix L, MacWilliam L, Finlayson GS, Reed M (2007) The effect of socioeconomic status on bone density testing in a public health-care system. Osteoporos Int 18:153–158

Lou Y, Edmonds SW, Jones MP, Ullrich F, Wehby GL, Cram P, Wolinsky FD (2016) Predictors of bone mineral density testing among older women on Medicare. Osteoporos Int 27:3577–3586

Rothmann MJ, Ammentorp J, Bech M, Barkmann R, Goemaere S, Hermann AP (2015) Self-perceived facture risk: factors underlying women’s perception of risk for osteoporotic fractures: the Risk-stratified Osteoporosis Strategy Evaluation study (ROSE). Osteoporos Int 26(2):689–697

Edmonds SW, Solimeo SL, Nguyen VT, Wright NC, Roblin DW, Saag KG, Cram P (2017) Understanding preferences for osteoporosis information to develop an osteoporosis patient education brochure. Perm J 21:16–024

Roh YH, Koh YD, Noh JH, Gong HS, Baek GH (2017) Effect of health literacy on adherence to osteoporosis treatment among patients with distal radius fracture. Arch Osteoporos 12:42

European Tobacco control Status report 2014. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/248418/European-Tobacco-Control-Status-Report-2014-Eng.pdf. Accessed 21 Marts 2017

Bridges MJ, Ruddick S (2010) Can self-reported height and weight be used to calculate 10 year risk of osteoporotic fracture? J Nutr Health Aging 14:611–613

Acknowledgements

Participants in the ROSE study and technical staff in the four involved hospitals: Odense University Hospital, Odense; Hospital of Funen, Nyborg; Hospital of Southwest Denmark, Esbjerg; and Sygehus Lillebælt Hospital, Kolding, Denmark, and Claire Gudex for editorial support.

Funding

The ROSE study was supported by INTERREG 4A, the region of Southern Denmark, and Odense University Hospital. The funding agencies had no direct role in the conduct of the study, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or the preparation, review, and final approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

All authors have completed the authorship and disclosure form. S Möller, T Holmberg, M Bech, J Gram, R Barkmann, CC Glüer, and KH Rubin have no conflict of interest. MJ Rothmann has received speaker fee from Eli Lilly. M Hoiberg is full-time employee of Boehringer-Ingelheim Norway KS (currently). AP Hermann serves on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Amgen, and she has received research funding from Eli Lilly, speaker fee from Eli Lilly, GSK, Genzyme, and Amgen, and K Brixen received funding from Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Amgen, Novartis, and NPS, all outside the submitted work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rothmann, M.J., Möller, S., Holmberg, T. et al. Non-participation in systematic screening for osteoporosis—the ROSE trial. Osteoporos Int 28, 3389–3399 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4205-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-4205-y