Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

This manuscript of Chapter 4 of the International Urogynecological Consultation (IUC) on Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) reviews the literature and makes recommendations on the definition of success in the surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse.

Methods

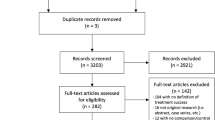

An international group containing seven urogynecologists performed an exhaustive search of the literature using two PubMed searches and using PICO methodology. The first search was from 01/01/2012–06/12/2022. A second search from inception to 7/24/2022 was done to access older references. Publications were eliminated if not relevant to the clinical definition of surgical success for the treatment of POP. All abstracts were reviewed for inclusion and any disagreements were adjudicated by majority consensus of the writing group. The resulting list of articles were used to inform a comprehensive review and creation of the definition of success in the surgical treatment of POP.

Outcomes

The original search yielded 12,161 references of which 45 were used by the writing group. Ultimately, 68 references are included in the manuscript. For research purposes, surgical success should be primarily defined by the absence of bothersome patient bulge symptoms or retreatment for POP and a time frame of at least 12 months follow-up should be used. Secondary outcomes, including anatomic measures of POP and related pelvic floor symptoms, should not contribute to a definition of success or failure. For clinical practice, surgical success should primarily be defined as the absence of bothersome patient bulge symptoms. Surgeons may consider using PASS (patient acceptable symptom state) or patient goal attainment assessments, and patients should be followed for a minimum of at least one encounter at 6–12 weeks post-operatively. For surgeries involving mesh longer-term follow-up is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

References

Kowalski JT, Mehr A, Cohen E, Bradley CS. Systematic review of definitions for success in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1697–704.

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:600–9.

Collins SA, O’Shea M, Dykes N, et al. International Urogynecological Consultation: clinical definition of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:2011–9.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Tan JS, Lukacz ES, Menefee SA, Powell CR, Nager CW, SAN DIEGO PELVIC FLOOR C. Predictive value of prolapse symptoms: a large database study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:203–9 (discussion 09).

Harvey MA, Chih HJ, Geoffrion R, et al. International Urogynecology Consultation Chapter 1 Committee 5: relationship of pelvic organ prolapse to associated pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms: lower urinary tract, bowel, sexual dysfunction and abdominopelvic pain. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:2575–94.

Sung VW, Rogers RG, Barber MD, Clark MA. Conceptual framework for patient-important treatment outcomes for pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:414–9.

Dieter AA, Halder GE, Pennycuff JF, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures for use in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2023.

Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1388–95.

Barber MD, Walters MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:103–13.

Cichowski S, Grzybowska ME, Halder GE, et al. International Urogynecology Consultation: Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROs) use in the evaluation of patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:2603–31.

Srikrishna S, Robinson D, Cardozo L. Validation of the Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I) for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:523–8.

Mamik MM, Rogers RG, Qualls CR, Komesu YM. Goal attainment after treatment in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(488):e1-5.

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–7.

Chmielewski L, Walters MD, Weber AM, Barber MD. Reanalysis of a randomized trial of 3 techniques of anterior colporrhaphy using clinically relevant definitions of success. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(69):e1-8.

Toozs-Hobson P, Swift S. POP-Q stage I prolapse: is it time to alter our terminology? Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:445–6.

Swift SE, Tate SB, Nicholas J. Correlation of symptoms with degree of pelvic organ support in a general population of women: what is pelvic organ prolapse? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:372–7 (discussion 77-9).

Kowalski JT, Melero GH, Mahal A, Genadry R, Bradley CS. Do patient characteristics impact the relationship between anatomic prolapse and vaginal bulge symptoms? Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:391–6.

Meister MR, Sutcliffe S, Lowder JL. Definitions of apical vaginal support loss: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:232.e1-32.e14.

Patnam R, Edenfield A, Swift S. Defining normal apical vaginal support: a relook at the POSST study. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:47–51.

Trutnovsky G, Robledo KP, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Definition of apical descent in women with and without previous hysterectomy: A retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0213617.

Dietz HP, Mann KP. What is clinically relevant prolapse? An attempt at defining cutoffs for the clinical assessment of pelvic organ descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:451–5.

Khoder W, Hom E, Guanzon A, Rose S, Hale D, Heit M. Patient satisfaction and regret with decision differ between outcomes in the composite definition of success after reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:613–20.

Lawndy SS, Withagen MI, Kluivers KB, Vierhout ME. Between hope and fear: patient’s expectations prior to pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1159–63.

Bradley CS, Nygaard IE. Vaginal wall descensus and pelvic floor symptoms in older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:759–66.

Gillingham A, Collins SA, Kenton K, et al. The influence of patients’ goals on surgical satisfaction. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:170–4.

Guldbrandsen K, Kousgaard SJ, Bjørk J, Glavind K. Patient goals after operation in the posterior vaginal compartment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;267:23–7.

Antosh DD, Kim-Fine S, Meriwether KV, et al. Changes in sexual activity and function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:922–31.

Bakali E, Johnson E, Buckley BS, Hilton P, Walker B, Tincello DG. Interventions for treating recurrent stress urinary incontinence after failed minimally invasive synthetic midurethral tape surgery in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:Cd009407.

Sappenfield EC, Tulikangas PK, Wang R. The impact of preoperative pelvic pain on outcomes after vaginal reconstructive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:564.e1-64.e9.

Gore A, Kenne KA, Kowalski JT, Bradley CS. Pelvic pain and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction in women seeking treatment for prolapse. Urogynecology (Hagerstown). 2023;29:225–33.

Borahay MA, Zeybek B, Patel P, Lin YL, Kuo YF, Kilic GS. Pelvic pain and apical prolapse surgery: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:704–11.

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Pain and activity after vaginal reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:233.e1-33.e16.

Shatkin-Margolis A, Crisp CC, Morrison C, Pauls RN. Predicting pain levels following vaginal reconstructive surgery: who is at highest risk? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:172–5.

Kavvadias T, Baessler K, Schuessler B. Pelvic pain in urogynaecology. Part I: evaluation, definitions and diagnoses. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:385–93.

Weber AM, Abrams P, Brubaker L, et al. The standardization of terminology for researchers in female pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:178–86.

Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:795–806.

Siddiqui NY, Gregory WT, Handa VL, et al. American urogynecologic society prolapse consensus conference summary report. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:260–3.

Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1557–66.

Lee U, Raz S. Emerging concepts for pelvic organ prolapse surgery: what is cure? Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:62–7.

Lee U, Wolff EM, Kobashi KC. Native tissue repairs in anterior vaginal prolapse surgery: examining definitions of surgical success in the mesh era. Curr Opin Urol. 2012;22:265–70.

Jelovsek JE, Gantz MG, Lukacz ES, et al. Subgroups of failure after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and associations with quality of life outcomes: a longitudinal cluster analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:504.e1-04.e22.

Jelovsek JE, Gantz MG, Lukacz E, et al. Success and failure are dynamic, recurrent event states after surgical treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:362.e1-62.e11.

Toozs-Hobson P, Freeman R, Barber M, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for reporting outcomes of surgical procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:415–21.

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–6.

Milani AL, Damoiseaux A, IntHout J, Kluivers KB, Withagen MIJ. Long-term outcome of vaginal mesh or native tissue in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:847–58.

Hansen BL, Dunn GE, Norton P, Hsu Y, Nygaard I. Long-term follow-up of treatment for synthetic mesh complications. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20:126–30.

Toozs-Hobson P, Bach F, Daly JO, Klarskov N. Minimum standards for reporting outcomes of surgery in urogynaecology. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:1387–90.

Guldberg R, Brostrom S, Hansen JK, et al. The Danish Urogynaecological Database: establishment, completeness and validity. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:983–90.

Jha S, Hillard T, Monga A, Duckett J. National BSUG audit of stress urinary incontinence surgery in England. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1337–41.

Keltie K, Elneil S, Monga A, et al. Complications following vaginal mesh procedures for stress urinary incontinence: an 8 year study of 92,246 women. Sci Rep. 2017;7:12015.

Barber MD, Neubauer NL, Klein-Olarte V. Can we screen for pelvic organ prolapse without a physical examination in epidemiologic studies? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:942–8.

Weber LeBrun EE, Lynch LD, Peterson HV, Pena SR, Ruder K, Vasilopoulos T. Design and early experience with a real-world surgical registry. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2018;24:341–6.

Jha S, Cutner A, Moran P. The UK national prolapse survey: 10 years on. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:795–801.

Brubaker L, Shull B. EGGS for patient-centered outcomes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:171–3.

Thompson JC, Cichowski SB, Rogers RG, et al. Outpatient visits versus telephone interviews for postoperative care: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1639–46.

Lee DD, Arya LA, Andy UU, Harvie HS. Video virtual clinical encounters versus office visits for postoperative care after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:432–8.

Karjalainen PK, Mattsson NK, Jalkanen JT, Nieminen K, Tolppanen AM. Minimal important difference and patient acceptable symptom state for PFDI-20 and POPDI-6 in POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:3169–76.

Maksymowych WP, Gooch K, Dougados M, et al. Thresholds of patient-reported outcomes that define the patient acceptable symptom state in ankylosing spondylitis vary over time and by treatment and patient characteristics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:826–34.

Sanderson DJ, Zavez A, Meekins AR, et al. The patient acceptable symptom state in female urinary incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2022;28:33–9.

Pilzek AL, Raker CA, Sung VW. Are patients’ personal goals achieved after pelvic reconstructive surgery? Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:347–50.

Sung VW, Wohlrab KJ, Madsen A, Raker C. Patient-reported goal attainment and comprehensive functioning outcomes after surgery compared with pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:659.e1-59.e7.

Robinson D, Prodigalidad LT, Chan S, et al. International Urogynaecology Consultation chapter 1 committee 4: patients’ perception of disease burden of pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33:189–210.

Hullfish KL. Pelvic floor dysfunction–what do women really want? J Urol. 2008;179:2092–3.

Lowenstein L, FitzGerald MP, Kenton K, et al. Patient-selected goals: the fourth dimension in assessment of pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:81–4.

Mahajan ST, Elkadry EA, Kenton KS, Shott S, Brubaker L. Patient-centered surgical outcomes: the impact of goal achievement and urge incontinence on patient satisfaction one year after surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:722–8.

Lawndy SS, Kluivers KB, Milani AL, Withagen MI, Hendriks JC, Vierhout ME. Which factors determine subjective improvement following pelvic organ prolapse 1 year after surgery? Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:543–9.

Siddiqui NY, Dunivan GC, Chermansky CJ, Bradley CS, American Urogynecologic Society Scientific C. Deciding our future: consensus conference summary report. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:159–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Population

("Pelvic Organ Prolapse"[majr] OR "Cystocele"[ti] OR "rectocele"[ti] OR "enterocele"[ti] OR (("Pelvic Organ*"[ti] OR "uterine"[ti] OR "urogenital"[ti] OR "urinary bladder"[ti] OR "vaginal"[ti]) AND ("Prolapse*"[ti] OR "descent"[ti])))

Intervention

AND

("Gynecologic Surgical Procedures"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "Hysterectomy, Vaginal"[Mesh] OR "vaginal hysterectom*"[tiab] OR "surger*"[tiab] OR "surgical"[tiab] OR (("anterior"[tiab] OR "posterior"[tiab]) AND "colporrhaph*"[tiab]) OR (("apical"[tiab] OR "vault"[tiab]) AND ("suspension*"[tiab] OR "fixation*"[tiab])) OR "uterosacral ligament suspension*"[tiab] OR "Manchester fothergill"[tiab] OR "colpocleisis"[tiab] OR "labhart"[tiab] OR "lefort"[tiab] OR "perineoplast*"[tiab] OR "levatorplast*"[tiab])

Outcome

AND

("Treatment Outcome"[Mesh] OR "outcome*"[tiab] OR "bulge*"[tiab] OR "bulging"[tiab] OR "goal attainment"[tiab] OR "patient-reported goal*"[tiab] OR "Goals"[Mesh] OR "Surveys and Questionnaires"[Mesh] OR "questionnaire*"[tiab] OR "survey*"[tiab] OR "PFDI-20"[tiab] OR "pelvic floor disability index"[tiab] OR "pelvic floor distress inventory"[tiab] OR "HRQoL"[tiab] OR "health-related quality of life"[tiab] OR "PGII"[tiab] OR "patient global impression of improvement"[tiab] OR "UDI-6"[tiab] OR "urogenital distress inventory"[tiab] OR "urinary distress inventory"[tiab] OR "iciq SF"[tiab] OR "ICIQ-UI SF"[tiab] OR "Urinary Incontinence Short Form"[tiab] OR "international consultation of incontinence questionnaire"[tiab] OR "IIQ7"[tiab] OR "IIQ-7"[tiab] OR "incontinence impact questionnaire"[tiab] OR "KHQ"[tiab] OR "King's health questionnaire"[tiab] OR "PISQ12"[tiab] OR "PISQ-12"[tiab] OR PISQ-IR[tiab] OR "VAS"[tiab] OR "visual analogue scale"[tiab] OR "POPIQ-7"[tiab] OR "PFIQ"[tiab] OR "pelvic organ prolapse impact questionnaire"[tiab] OR "pelvic floor impact questionnaire"[tiab] OR "Retreatment"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "retreatment"[tiab] OR "Pessaries"[Mesh] OR "Pessar*"[tiab] OR (("new"[tiab] OR "persistent"[tiab]) AND (("Urinary Bladder"[Mesh] OR "bladder"[tiab] OR "bowel"[tiab])) AND "symptom*"[tiab]) OR "Sexual Health"[Mesh] OR "sexual"[tiab] OR "Pain"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "pain"[tiab])

AND ("2012/01/01"[Date—Publication]: "2030/12/31"[Date—Publication]) NOT ("animals"[mesh] NOT "humans"[mesh])

Appendix 2

(surgery) AND ((anterior prolapse) OR (apical prolapse) OR (cystocele) OR (descending uterus) OR (descensus) OR (enterocele) OR (genital hiatus) OR (normal pelvic organ support) OR (paravaginal defect) OR (pelvic organ prolapse) OR (POP-Q) OR (posterior prolapse) OR (posthysterectomy prolapse) OR (prolapse) OR (prolapse symptoms) OR (rectocele) OR (uterine prolapse) OR (vaginal prolapse) OR (vaginal vault prolapse)) NOT ((hernia) OR (valve) OR (vitreous) OR (eyelid) OR (casereports[Filter])) AND ((fft[Filter]) AND (english[Filter]))

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kowalski, J.T., Barber, M.D., Klerkx, W.M. et al. International urogynecological consultation chapter 4.1: definition of outcomes for pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J 34, 2689–2699 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05660-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05660-9