Abstract

Introduction

Rectocele is a common condition, which on imaging is defined by a pocket identified on Valsalva or defecation. Cut-offs of 10 and 20 mm for pocket depth have been described. This study analyses the correlation between rectocele depth and symptoms of bowel dysfunction to define a cut-off for the diagnosis of “significant rectocele” on ultrasound.

Methods

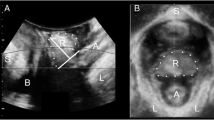

A retrospective study using 564 archived data sets of patients seen at tertiary urogynaecological clinics. Patients underwent a standardised interview including a set of questions regarding bowel function, and translabial 3D/4D ultrasound. Assessments were undertaken supine and after voiding. Rectocele depth was measured on Valsalva.

Results

Out of 564, data on symptoms was missing in 18 and ultrasound volumes in 25, leaving 521. Mean age was 56 years (range 18–86), mean BMI 29 (17–56). Presenting symptoms were prolapse (51 %), constipation (21 %), vaginal digitation (17 %), straining at stool (46 %), incomplete bowel emptying (41 %) and faecal incontinence (10 %). A clinically significant rectocele (ICS POPQ stage ≥2) was found in 48 % (n=250). In 261 women a rectal diverticulum was identified, of an average depth of 17 (SD, 7) mm. On ROC statistics a cut- off of 15 mm in depth provided optimal sensitivities of 66 % for vaginal digitation and 63 % for incomplete emptying, and specificities of 52 and 57 % respectively.

Conclusions

Rectocele depth is associated with symptoms of obstructed defecation. A “clinically significant” rectocele may be defined as a diverticulum of the rectal ampulla of ≥15 mm in depth, although poor test characteristics limit clinical utility of this cut-off.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Zbar A, Lienemann A, Fritsch H et al (2003) Rectocele: pathogenesis and surgical management. Int J Colorectal Dis 18:369–384

Kahn MA, Stanton SL (1997) Posterior vaginal wall prolapse and its management. Contemp Rev Obstet Gynecol 9:303–310

Andromanakos N, Skandalakis P, Troupis T, Filippou D (2006) Constipation of anorectal outlet obstruction: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21:638–646

Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L (1999) The anatomic and functional variability of rectoceles in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 10(2):96–99

Burrows LJ, Meyn LA, Walters MD, Weber AM (2004) Pelvic symptoms in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 104(5 Pt 1):982–988

Dietz HP (2014) How I do it: Translabial ultrasound in the investigation of posterior compartment vaginal prolapse and defecatory disorders. Tech Coloproctol 18(5):481–494

Beer-Gabel M, Assoulin Y, Amitai M, Bardan E (2008) A comparison of dynamic transperineal ultrasound (DTP-US) with dynamic evacuation proctography (DEP) in the diagnosis of cul de sac hernia (enterocele) in patients with evacuatory dysfunction. Int J Colorectal Dis 23:513–519

Dietz HP, Beer-Gabel M (2012) Ultrasound in the investigation of posterior compartment vaginal prolapse and obstructed defecation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 40:14–27

Steensma AB, Oom DM, Burger CW, Schouten WR (2010) Assessment of posterior compartment prolapse: a comparison of evacuation proctography and 3D transperineal ultrasound. Colorectal Dis 12(6):533–539

Perniola G, Shek C, Chong CC, Chew S, Cartmill J, Dietz HP (2008) Defecation proctography and translabial ultrasound in the investigation of defecatory disorders. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 31:567–571

Dietz HP, Korda A (2005) Which bowel symptoms are most strongly associated with a true rectocele? Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 45:505–508

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K et al (1996) The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 175(1):10–17

Dietz HP (2004) Ultrasound imaging of the pelvic floor: 3D aspects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 23(6):615–625

Dietz HP, Haylen BT, Broome J (2001) Ultrasound in the quantification of female pelvic organ prolapse. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 18(5):511–514

Dietz HP, Steensma AB (2005) Posterior compartment prolapse on two- dimensional and three- dimensional pelvic floor ultrasound: the distinction between true rectocele, perineal hypermobility and enterocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 26:73–77

Tan L, Guzman Rojas R, Dietz H (2014) The repeatability of sonographic measures of functional pelvic floor anatomy. Neurourol Urodyn 33:1058–60

Dietz HP, Guzman Rojas R, Shek KL (2014) Postprocessing of pelvic floor ultrasound data: how repeatable is it? Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 54(6):553–557

Dietz H, Clarke B (2005) The prevalence of rectocele in young nulliparous women. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 45:391–394

Richardson AC (1993) The rectovaginal septum revisited: its relationship to rectocele and its importance in rectocele repair. Clin Obstet Gynecol 36(4):976–983

Guzman Rojas R, Shek KL, Kamisan Atan I, Dietz HP (2013) Defect-specific rectocele repair: medium-term subjective and objective outcomes. Neurourol Urodyn 32(6):868–870

Rachaneni S, Kamisan Atan I, Guzman Rojas RA, Dietz H (2014) Can defects of the rectovaginal septum be palpated? Abstract, Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Urogynecological Association, Washington

Santoro G, Wieczorek AP, Dietz HP et al (2011) State of the art: an integrated approach to pelvic floor ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 37:381–396

Barber M, Walters M, Bump R (2005) Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol 193:103–113

Alam P, Kamisan Atan I, Guzman Rojas RA, Mann K, Dietz HP (2014) The ‘bother’ of obstructed defecation. Int Urogynecol J 25(S1):S114–S115

Conflict of interest

H.P. Dietz and K.L. Shek have received unrestricted educational grants from GE Medical.

Contributions

H.P. Dietz: project development, manuscript writing; X. Zhang: data entry, analysis; K.L. Shek: analysis, manuscript editing; R. Guzman Rojas: data entry, analysis, manuscript editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dietz, H.P., Zhang, X., Shek, K.L. et al. How large does a rectocele have to be to cause symptoms? A 3D/4D ultrasound study. Int Urogynecol J 26, 1355–1359 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2709-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2709-6