Abstract

Growth theory argues that thresholds can lead to multiple growth regimes, which are reflected in heterogeneous patterns of cross-country convergence and divergence. We study sectoral convergence patterns by using a new longitudinal sectoral database for 65 developed and developing countries. We employ an econometric method, quantile smoothing splines, which explicitly allows for identification of parameter heterogeneity both with regard to initial conditions (X-heterogeneity) and growth performances (Y-heterogeneity). Findings suggest that convergence is rather the exception than the rule.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In what follows, we will use the term country-sectors to denote the observations in our samples (i.e. the Dutch agricultural sector, or the Indonesian manufacturing sector).

See the theoretical models reviewed in section 2 of this paper.

The 14 countries in BJ’s sample are Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and West Germany.

For 49 countries, the series start in 1970; for many Eastern European countries, reliable data is only available from 1995 onwards.

The main sectors are: Agriculture, Mining, Manufacturing, Utilities, Construction, Wholesale and retail trade, Transport, storage and communication, Financial services, and Non-market services (community social and personal services, and government services). The data are publicly available for free at www.ggdc.net and www.wiod.org.

Details about the estimation of the sectoral PPPs for 2005 can be found in Inklaar and Timmer (2013).

In a reply to Sørensen (2001), Bernard and Jones (2001) argued that this systematic finding is a consequence of the Balassa-Samuelson effect. In countries with high labor productivity growth in manufacturing, relative manufacturing prices tend to decline rapidly; hence, initial value added in manufacturing is underestimated in high productivity growth countries if GDP PPPs associated with a later base year are used to deflate its value added, leading to a tendency to find β-convergence.

In a recent paper, Rodrik (2013) focused on the manufacturing sector, finding strong evidence for unconditional labor productivity convergence in a sample that contains even more non-OECD countries than ours. His analysis, however, is based on UNIDO industrial survey data, which typically only considers the formal economy, while our data also take informal economic activity into account.

See Koenker (2005) for an extended exposition.

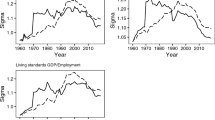

In the period 1970–2009, labor productivity growth in Denmark’s agricultural sector grew on average by 7.3 % per year, while Venezuela’s corresponding figure amounted to a tiny 0.7 %. We borrowed the term ‘law of motion’ from Bernard and Durlauf (1996).

The number of linearly interpolated y i s (p λ ) is at least 2 and at most the number of observations n. The number of linear segments in the fitted function associated with the smoothing parameter λ equals (n - p λ +1).

In view of the limited number of observations, we do not produce regressions for “extreme” quantiles (such as τ = 0.1 and 0.9). Programs for quantile regressions are available in R and Stata. Code to run quantile smoothing splines is currently only available in R (Ng and Maechler, 2011).

Unconstrained linear quantile smoothing splines were estimated using the COBS package, version 1.1–3.5 (He and Ng, 1999).

An all-encompassing approach to assessing the statistical significance of results of analyses based on quantile smoothing splines would also consider the stochastic nature of the existence and location of the kinks. Are the kinks statistically significant, and what are the confidence intervals for the initial productivity level where a kink is located? In principle, simultaneously testing for the existence of kinks and the significance of slopes should also be possible using a bootstrapping approach. However, we consider that developing such a testing framework and carefully assessing its statistical properties would be beyond the scope of this paper.

Appendix B shows that the absence of kinks for manufacturing and services is not due to the value of the parameter λ that follows from the Schwarz Information Criterion (Eq. 7)

References

Abramovitz M (1986) “Catching Up, forging ahead, and falling behind”. J Econ Hist 46:385–406

Acemoglu D, Aghion P, Zilibotti F (2006) “Distance to frontier, selection and economic growth”. J Eur Econ Assoc 4:37–74

Aghion P, Howitt PW (2006) Joseph Schumpeter lecture - appropriate growth policy: a unifying framework”. J Eur Econ Assoc 4:269–314

Azariadis C, Drazen A (1990) Threshold externalities in economic development”. Q J Econ 105:501–526

Barreto R, Hughes A (2004) Underperformers and overachievers: a quantile regression analysis of growth”. Econ Rec 80:17–35

Basu S, Weil DN (1998) Appropriate technology and growth”. Q J Econ 113:1025–1054

Baumol WJ (1986) “Productivity growth, convergence, and welfare: what the long-Run data show”. Am Econ Rev 76:1072–1085

Bernard AB, Durlauf SD (1996) Interpreting tests of the convergence hypothesis”. J Econ 71:161–173

Bernard AB, Jones CI (1996) Comparing apples to oranges: productivity convergence and measurement across industries and countries”. Am Econ Rev 86:1216–1238

Bernard AB, Jones CI (2001) Comparing apples to oranges: productivity convergence and measurement across industries and countries: reply”. Am Econ Rev 91:1168–1169

Castellacci F (2008) “Technology clubs, technology gaps and growth trajectories”. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 19:301–314

Castellacci F (2011) Closing the technology Gap?”. Rev Dev Econ 15:180–197

Castellacci F, Archibugi D (2008) The technology clubs: the distribution of knowledge across nations”. Res Policy 37:1659–1673

de Vries GJ, Timmer MP, de Vries K (2013) “Structural transformation in africa: static gains, dynamic losses”, GGDC research memorandum 136. University of, Groningen

Duarte M, Restuccia D (2010) The role of the structural transformation in aggregate productivity”. Q J Econ 125:129–173

Durlauf SN (1993) Nonergodic economic growth”. Rev Econ Stud 60:349–366

Durlauf SN, Johnson PA (1995) Multiple regimes and cross-country growth behaviour”. J Appl Econ 10:365–384

Durlauf, S.N., P.A. Johnson and J. Temple (2005), “Growth Econometrics”, in: Aghion, Ph. and S. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth (Elsevier- North Holland), pp. 555–667.

Fagerberg J (1994) Technology and international differences in growth rates”. J Econ Lit 32:1147–1175

Fagerberg J, Verspagen B (2002) “Technology-gaps, innovation-diffusion and transformation: an evolutionary interpretation”. Res Policy 31:1291–1304

Fagerberg J, Srholec M (2008) “National innovation systems, capabilities and economic development”. Res Policy 37:1417–1435

Filippetti A, Peyrache A (2011) The patterns of technological capabilities of countries: a dual approach using composite indicators and data envelopment analysis”. World Dev 39:1108–1121

Galor O, Moav O (2000) “Ability-based technological transition, wage inequality, and economic growth”. Q J Econ 115:469–497

Harberger AC (1987) Comment”. In: Fischer S (ed) NBER macroeconomics annual 1987. NBER, Cambridge, pp 255–258

He X, Ng P (1999) COBS: qualitatively constrained smoothing Via linear programming”. Comput Stat 14:315–337

Holst Milton Bache S, Moller Dahl C, Tang Kristensen J (2013) Headlights on tobacco road to Low birthweight outcomes”. Empir Econ 44:1593–1633

Howitt P (2000) Endogenous growth and cross-country income differences”. Am Econ Rev 90:829–846

Howitt P, Mayer-Foulkes D (2005) R&D, implementation and stagnation: a Schumpeterian theory of convergence clubs”. J Money Credit Bank 37:147–177

Inklaar R, Timmer MP (2009) Productivity convergence across industries and countries: the importance of theory-based measurement”. Macroecon Dyn 13:218–240

Inklaar, R., and M.P. Timmer (2013) “The Relative Price of Services." Review of Income and Wealth, forthcoming.

Kalirajan K (2000) “Restrictions on trade in distribution services”. Productivity Commission Staff Research Paper, AusInfo, Canberra

Kelly M (2001) Linkages, thresholds, and development”. J Econ Growth 6:39–53

Koenker R (2004) Quantile regression for longitudinal data”. J Multivar Anal 91:74–89

Koenker R (2005) Quantile regression, econometric society monograph no. 38. Cambridge University Press, New York

Koenker R, Bassett G Jr (1978) Regression quantiles”. Econometrica 46:33–50

Koenker R, Bassett G Jr (1982) Robust tests for heteroscedasticity based on regression quantiles”. Econometrica 50:43–61

Koenker R, Ng P, Portnoy S (1994) Quantile smoothing splines”. Biometrika 81:673–680

Koenker R, Xiao Z (2002) Inference on the quantile regression process”. Econometrica 70:1583–1612

Krüger, J. (2009), “Inspecting the Poverty-Trap Mechanism: A Quantile Regression Approach”, Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics & Econometrics, vol. 13 (3), Article 2.

Mankiw NG, Romer D, Weil DN (1992) A contribution to the empirics of economic growth”. Q J Econ 107:407–436

Mattoo A, Rathindran R, Subramanian A (2006) Measuring services trade liberalization and its impact on economic growth”. J Econ Integr 21:64–98

Mulder P, de Groot HLF (2007) Sectoral energy- and labor-productivity convergence”. Environ Resour Econ 36:85–112

Nelson R, Phelps E (1966) “Investments in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth”. Am Econ Rev 56:69–75

Ng, P.T. and M. Maechler (2011), “COBS – Constrained B-splines (Sparse matrix based)”, code available at http://stat.ethz.ch/CRAN/web/packages/cobs/).

O’Mahony M, Timmer MP (2009) “Output, input and productivity measures at the industry level: the EU KLEMS database”. Econ J 119:F374–F403

Pritchett L (1997) “Divergence, Big time”. J Econ Perspect 11:3–17

Quah DT (1993) Galton’s fallacy and tests of hte convergence hypothesis”. Scand J Econ 95:427–443

Rodrik D (2013) Unconditional convergence in manufacturing”. Q J Econ 128(1):165–204

Saviotti P, Pyka A (2011) Generalized barriers to entry and economic development”. J Evol Econ 21:29–52

Sørensen A (2001) Comparing apples to oranges: productivity convergence and measurement across industries and countries: comment”. Am Econ Rev 91:1160–1167

Temple J (1999) The New growth evidence”. J Econ Lit 37:112–156

Timmer MP, Dietzenbacher E, Los B, Stehrer R, de Vries GJ (2014) “The world input–output database: content, concepts, and applications”, GGDC research memorandum 144. University of, Groningen

Timmer MP, de Vries GJ (2009) Structural change and growth accelerations in Asia and Latin america: a New sectoral data Set”. Cliometrica 3:165–190

Verspagen B (1991) A New empirical approach to catching Up or falling behind”. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 2:488–509

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper benefitted comments from and discussions with participants at the DIME conference in Maastricht, the Globelics Conference in Mexico City, the North-American Productivity Workshop at New York University, a seminar at the University of Groningen, communication with Roger Koenker and Pin Ng, and detailed comments by two anonymous referees and the Editor of this journal.

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Section 4.2 explains the role of λ, which is a smoothing parameter for the estimated splines. In our empirical application of quantile smoothing splines, we choose the smoothing parameter λ such that the SIC criterion in Eq. 7 reaches its global minimum. The results indicate that X-heterogeneity appears to play a limited role in the convergence patterns in Agriculture, Manufacturing and Services. Here, we analyze the sensitivity of these results to the selection of lambda.

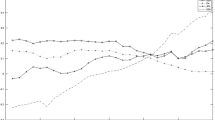

For Agriculture, we find that the SIC criterion leads us to choose λ = 1403, for all three quantiles. However, a plot of the SIC criterion against λ suggests that the value of SIC hardly increases if λ is stepwise reduced, until λ = 10. For values lower than 10, SIC is considerably higher. Hence, λ = 10 might serve as a lower bound to examine the absence of X-heterogeneity (note that if λ = 0, all observations for a quantile are linearly interpolated). The results for Agriculture obtained for λ = 10 are depicted in Fig. 2. A similar strategy was followed for Manufacturing and Services. All results clearly suggest that the absence or minor role of thresholds in the sectoral productivity dynamics is a result that is not sensitive to the choice of other reasonable values for the smoothing parameter λ.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castellacci, F., Los, B. & de Vries, G.J. Sectoral productivity trends: convergence islands in oceans of non-convergence. J Evol Econ 24, 983–1007 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-014-0386-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-014-0386-0