Abstract

This study explores the impact of unconditional cash transfers on the multiple dimensions of women’s empowerment in Pakistan. Emphasizing the importance of cultural and religious norms, empowerment is considered as a latent construct manifested through three distinct choice dimensions, viz., “self,” “familial,” and “economic.” For the empirical estimation, a structural equation model is used on the country-representative Impact Evaluation Survey data of 2015–16 for the Benazir Income Support Program. The measurement model identifies various indicators for the dimensions considered. The results confirm the importance of providing cash transfers to the country's poorest women in all three dimensions, while the impact on self-choices is almost 40% that of the impact on the other two aspects of empowerment. Our findings provide recommendations for the successful implementation of social assistance programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last few decades, women’s empowerment has emerged as a primary concern of the sustainable development agenda. It is also viewed as a significant measure of social development. Both policymakers and academics are searching for ways to enhance women’s empowerment, particularly in developing countries where gender imbalances persist.Footnote 1

Many studies across various disciplines discuss the measurement of women’s empowerment and analyze the impacts of policies and programsFootnote 2 to expand empowerment as an outcome of sustainable development (Adato et al. 2000; Narayan et al. 2009; Schuler and Hashemi 1994). Most of these studies measure empowerment using proxy indicatorsFootnote 3 while not encompassing multiple dimensions and ignoring cultural norms and traditions, in defining empowerment and measuring impacts of policy interventions. We choose Pakistan as a case study to fill these gaps—a country for which relatively little research has been published on the impact of cash transfer programs on women’s empowerment.Footnote 4 Our study evaluates the impacts of unconditional cash transfers provided by the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) in expanding empowerment for women, the major beneficiaries. We estimate the changes in various domains of women’s empowerment using a structural equation model (SEM).

Conceptually, women’s empowerment is a complex multidimensional process rooted in Sen’s capability approach (Chakrabarti and Biswas 2012; Samman and Santos 2009) and is context-specific (Kabeer 1999; Malhotra and Mather 1997; Mason and Smith 2003). While it is evident that agency enables women to define self-interest, make choices. and pursue capabilities (Kabeer 2001; Nussbaum 2000; Sen 1989, 2001), the measurement of agency must also focus on access to and control over assets, including physical, financial, human and social capital, and the ability to make decisions. Much of the literature uses information related to decision-making to infer empowerment (see, for example, Ashraf 2009; Braaten and Martinsson 2015; Carlsson et al. 2012; De Brauw et al. 2014; Peterman et al. 2015; Baranov et al. 2020). This is particularly useful on two accounts. First, this approach disentangles the puzzle of empowerment and brings us to the concept of agency. And secondly, it provides us with a measurement solution for such a complex and seemingly difficult concept by using self-reported decision-making in various domains of one’s life. For conceptual foundations, we follow Kabeer’s (1999) notion of empowerment and use decision-making and agency interchangeably as the crux or spirit of empowerment.

Several studies on women’s empowerment support the notion that the provision of social assistance to women improves welfare at the household level (Acharya and Bennett 1982; Attanasio and Lechene 2002; Deere and Doss 2006; Duflo 2003; Hoddinott and Haddad 1995; Schady and Rosero 2008; Yoong 2012; Ganle et al. 2015; Muralidharan and Nishith 2017). It is indeed rational to think that targeting cash grants directly and entirely to mothers would strengthen these women’s autonomy and decision-making power, strengthen their engagement in activities that lift their standing in the community, and bring them out of social and political isolation by cultivating links to other grantees and to the state itself. The existing empirical literature on various countries, however, does not provide ample and clear evidence of the effectiveness of cash transfers in expanding women’s empowerment. For example, micro-credit programs were found to increase women’s participation in household decision-making in Mexico (Angelucci et al. 2015), but no effect is found in India (Banerjee et al. 2015) and Pakistan (Said et al. 2019). However, Bandiera et al. (2020), Haushofer et al. (2019), and Kinyondo and Ntegwa (2023), among others, found improvement in the economic empowerment of women due to cash transfers,Footnote 5 despite more limited impacts on their decision-making power. These mixed effects could be explained by measurement issues related to decision-making, program implementation and delivery details, context-specific gender relations, and cultural norms. The apparent insignificance of cash transfers in improving empowerment is intriguing and suggests that the assumed mechanism through which a shift in women’s access to resources translates into her decision outcomes is not working out as first conceived by policymakers and program implementers.

This paper contributes to the growing literature in two main ways. First, it enriches the area of the literature that uses latent variables analysis to inform various domains of empowerment.Footnote 6 We define empowerment as a woman’s decision-making ability regarding her life choices, encompassing her “self” (the ability to act as an individual), “familial” (the ability to make choices about children), and “economic” (the ability to participate in the labor force and make decisions about household purchases and investments) choices.Footnote 7 Building on this definition and extending the latent variable model of women’s empowerment, this study presents a structural equation model to inform the construction of empowerment indices for women from the poorest households in Pakistan. Ballon (2018)Footnote 8 and Abreha et al. (2020) used multiple indicators, multiple causes (MIMIC) models to analyze women’s empowerment, although their models differ in structure, reflecting their different objectives. In the case of Ballon (2018), the objective was to estimate the different aspects of women’s empowerment as latent variables and to then apply stochastic dominance analysis to assess the relative importance of the different aspects of empowerment. In contrast, Abreha et al. (2020) used their model to estimate the different aspects of women’s empowerment to measure their association with children's health status. In our paper, we wish to assess the impact of unconditional cash grants on women’s empowerment, so our model differs from those of both Ballon (2018) and Abreha et al. (2020).Footnote 9

Second, our paper presents a study of women’s empowerment in the context of a country that, with its intricate gender relations and strong patriarchal norms and religious characteristics, with huge gender imbalances in almost every field of life, including access to basic education, healthcare delivery, employment, and income, is very different from the Latin American countries that are often considered in the literature on women’s empowerment.Footnote 10 While international empirical research is inconclusive on the effect of cash transfer on women’s empowerment, the available handful of studies found a positive impact of BISP on women’s mobility, tolerance of domestic violence, and sharing of household work (see Ambler and De Brauw, 2017; Waqas and Awan 2019a, b).Footnote 11 These studies are either based on samples from only one part of the country or evaluated the effect of BISP on women empowerment by a few selected outcome-related/decision-making variables like voting rights, women mobility, or labor market activities. On the contrary, our paper develops a comprehensive measure of women empowerment as a multidimensional construct incorporating gender roles and norms specific for the religious and cultural setting of Pakistan. This approach adds value in understanding the impact of cash transfer on various domains of women’s empowerment. We used the latest 2016 BISP Impact Evaluation data covering the whole country. The use of national representative data for evaluating the effectiveness of the BISP on women empowerment in the aforementioned three dimensions is advantageous compared to the qualitative focus group-based approach (see Ganle et al. 2015) or systematic survey method (Broady et al. 2016), as well as the popular but highly costly randomized controlled trial (RCT) approach (see for example, Baranov et al. 2020; Dhar et al. 2022) available in the literature.Footnote 12

Thus, our findings offer important considerations regarding social assistance programs’ gender-based targeting design and the consequent effects of those programs on women’s empowerment. This study complements a growing literature that indicates that unconditional cash transfer programs may be conducive to alleviating poverty and improving households’ well-being.Footnote 13

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the definition and conceptual framework of empowerment used in the study. Section 3 describes the main elements of the program; Sect. 4 presents the structural equation model; Sect. 5 describes the empirical results; and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Conceptual framework

The question of what constitutes women’s empowerment is a matter of continuing debate. Nonetheless, it is widely regarded as a multidimensional concept. For example, Anderson and Eswaran (2009), Saleem and Bobak (2005), and Sathar and Kazi (2000) use the term “autonomy” when measuring women’s empowerment in Bangladesh and Pakistan, and Adato et al. (2000) use the term “status” when measuring the impact of Progresa (a cash transfer program in Mexico) on women’s empowerment. Similarly, Ashraf (2009), Braaten and Martinsson (2015), Carlsson et al. (2012), De Brauw et al. (2014), and Peterman et al. (2015) use “decision-making” to analyze women’s empowerment, while “gender equality” is used by the World Bank. There is no clear demarcation between these terms, and they are often used interchangeably.

One of the most comprehensive theoretical foundations of women’s empowerment emerges from Sen’s capability approach. Sen (1985) puts forth a theoretical debate on empowerment being the enhancement of one’s agency, conceived as the enlargement of effective opportunities for women to live the life they want. Kabeer (1999), on the other hand, extends the definition and connects power, symbolizing the ability to make choices. She explains this process of empowerment in terms of three inter-related elements: resources, agency, and achievements. For our study, we operationalize empowerment as defined by Kabeer and approach it as a process comprising access to resources leading to agency and achievements as empowerment outcomes.

The literature suggests that “resources” and “agency” are the two most stated domains of empowerment (Acharya and Bennett 1982; Chen 1992). Some studies present resources as a pre-condition for empowerment, not a source; for example, Kishor (2000) analyzes resources such as education or employment as enabling factors of the empowerment process. But in societies like Pakistan, it is harder for a woman to exercise choice in accessing both material and human resources. Pakistani women are easily oppressed by their mothers-in-law, often accept domestic violence to keep the family intact, prefer sons over daughters, and relinquish their right to inheritance in favor of their male siblings (Chung and Gupta 2007; Winkvist and Akhtar 2000).

Alderman and Gertler (1997) analyze the differences in rates of human capital investment by gender due to differences in household resources. They find that the difference in price elasticities of educational attainment falls as family resources rise. Poorer families invest less in daughters relative to sons, and the difference in the level of discrimination between wealthier and poorer families grows as the price of human capital rises. In a study on gender difference in household expenditure on education in Pakistan, Aslam and Kingdon (2008) find significant biases toward male children in education-related expenditure in both the enrollment decision and the decision on private expenditure for schooling. Their results suggest that the observed strong gender difference in education expenditure is a within rather than an across household phenomenon. It is evident that equal access to resources is hard to practice in societies like Pakistan. Therefore, we assert that an increase in female-oriented “resources” such as a gender-targeted cash transfer program (e.g., BISP in Pakistan) provides opportunities that improve a woman’s ability to make decisions. We also suggest policies designed to alleviate poverty and raise incomes will reduce gender discrimination among the poor.

Early studies considered women with control over material resources and labor income as a robust measure of agency or empowerment.Footnote 14 Another branch of the literature uses bargaining models to measure female agency. In this context, a woman’s degree of empowerment is evaluated by the strength of her bargaining power within the household, and therefore, improvement in her status will enhance her decision-making ability or empowerment.Footnote 15 Shibata et al. (2020) and Agarwal (1994), among others, suggest that female bargaining power in rural areas depends on factors such as a woman’s ownership of land, her sources of income, her educational status, her access to family and tribal support systems, and support received from NGOs or the state. It is therefore by means of these parameters or factors that policy interventions may improve a woman’s bargaining position in the household and consequently her empowerment. Doss (2013) explains intra-household allocations via the impact of endowments, preferences, human resource investment prices, household resource levels, labor market opportunities, and marriage markets (see Behrman 1997 also). Women’s participation in household decision-making is considered an outcome or achievement or a manifestation of the agency.

Thus, while resources are critical for women’s empowerment, they are not always enough. Without women’s individual or collective ability to recognize and utilize resources in their own interests, resources cannot empower them. Having claimed that “agency” should be treated as the soul of empowerment, and resources and achievements as enabling conditions or sources of empowerment, correspondingly, another domain is necessary. Social settings, norms, and religious practices shape women’s ability to exercise agency. Most empirical models used to measure women’s empowerment ignore the complexities of gender relations beyond the household and the important role played by social norms, culture, values, and perceptions in the bargaining process. Ballon (2018) proposed a comprehensive approach to measure women’s empowerment, building on Sen’s capability approach and exploring intra-household gender dynamics. In her model, women’s empowerment is a latent variable reflected in the observed decisions made by women but shaped through available “resources” and determined by exogenous values and traditions. Jayachandran (2021a, b) argued that cultural norms help explain the large differences in female employment among countries at the same level of development. Thus, gender gaps in the labor market may be narrowed through policies attuned to cultural norms. Using a structural equation modeling approach, Bahadir-Yilmaz and Öz (2018) found a significant and negative effect of violence against female spouses on their level of autonomy, measured by participation in household-related decisions. They reported that the incidence of intimate partner violence (IPV) also diminishes with higher female autonomy. While looking at the impact of social norms on IPV, the authors find that IPV increases along with the husband’s commitment to social norms, upholding traditional gender roles characterized by women’s subordination and restricted agency. Chaudhuri and Yalonetzky (2018) demonstrated that social comparisons are possible using stochastic dominance techniques suited for multiple ordinal and dichotomous variables. Their empirical findings in India highlight that whenever these dominance conditions hold for a pair-wise comparison, the multidimensional autonomy distribution in one state is more desirable than in another one in terms of a broad range of criteria for the individual and social welfare evaluation of autonomy.

Based on the literature reviewed, we propose a framework of women’s empowerment that interlinks the following three aspects/dimensions.

2.1 Access to enabling resources as sources of empowerment: “economic” choice

A reliable source of income—like cash transfers—offers regularity and predictability of income and flows of resources that provide women with the security to plan and act. It also emphasizes just how significant social resources are to women’s empowerment. Education, health and fertility decisions, socio-demographic characteristics (including age, family size, family structure, and region), and religious and social norms each play a decisive role in determining women’s agency.Footnote 16 Haddad and Hoddinott (1994) find robust results suggesting that increasing women’s share of income increases spending on food and reduces the budget shares of alcohol and cigarettes for men. Similarly, Eswaran (2002) argues that expanding a woman’s autonomy within the household is positively linked with her bargaining power and is shown to reduce fertility rates and child mortality. Schuler and Hashemi (1994) find that participation in credit programs empowers women, mostly through enhancing their economic roles, and is positively correlated with the use of contraceptives. Allendorf (2007) argues that women's land rights also positively impact young children’s health since children of mothers with land ownership are significantly less likely to be severely underweight. She also finds that men receiving pensions have almost no effect on children’s nutritional status. Pre-marital enabling resources can ensure post-marital agency (Yount et al. 2016, 2018) and allow women to negotiate rights and physical safety within marriage (Miedema et al. 2016). In this study, we call this the “economic” dimension of empowerment.

2.2 An ability to exercise choice in household decision-making: “familial” choice

In our framework, agency refers to making decisions for oneself and the family (Gammage et al. 2016; Ghuman 2003; Malhotra and Mather 1997; Yount et al. 2016). The decision-making indicators are self-reported by the respondents and measured the capability of respondents to make decisions alone or jointly with their spouses. Several studies propose and use household decision-making as a measure of agency.Footnote 17 For the purpose of our study, we use decision-making in various domains of a woman’s life as a manifestation of agency and name this dimension “familial.”

2.3 The expression of equitable gender beliefs and attitudes (intrinsic agency or power within Footnote 18 ): “self”-choice

It can be argued that participation in poverty reduction programs may not impact social norms because such values and norms are deeply rooted in religion and culture. On the other hand, the normative structures that limit women’s decision-making may be altered through processes arising from individual actions in response to exogenous changes like gender-targeted cash transfer programs.Footnote 19 For example, restrictions on women’s freedom of movement and interactions with men who are not closely related to the family may relax as a result of cash transfer programs or other similar opportunities, and women’s access to social networks outside the family may increase along with their presence in the public sphere. Irrespective of whether they have been intentionally fostered through development policies (as opposed to being merely by-products of policies with other aims), such changes may eventually lead to a shift in women’s positions within family systems, or markets, and may represent a transformation in gender norms. This is the “self”-aspect of empowerment.

The key features of our conceptual framework explained above suggest that empowerment is a “process.” Malhotra et al. (2002) list four major hurdles when measuring empowerment, including: “the use of direct measures as opposed to proxy indicators, the lack of availability and use of data across time, the subjectivity inherent in assessing processes, and the shifts in the relevance of indicators over time” (p. 20). In response, we make efforts to measure empowerment using direct indicators (i.e., based on women's responses to specific survey questions about their decisions and mobilityFootnote 20) as these provide the closest measures in specific cultural contexts. Secondly, we attempt to measure empowerment at the individual level as a function of the individual’s decision-making and community norms. As discussed above, in our model, “empowerment” can be manifested through the multidimensional elements representing three distinct choices/dimensions of women’s empowerment: “economic” (participation in the labor force as well as deciding on investment and household purchase); “familial” (choices made particularly for the children’s well-being); and “self” (that is the ability to act as an individual or self). These choices are determined through several decision outcomes/indicators (observed self-reported indicators of decision-making in various domains such as minor household purchases, labor force participation, child education, family planning, having another child, mobility in social participation, and marketplaces, etc.). The norm/attitude is that men only make the decisions that influence these outcomes. In our estimation model, “choices” interact into a system of structural equations where a latent or unobserved variable is specified to measure empowerment. This latent variable represents a woman's decision-making ability that is (at least partially) measured by her decision outcomes and is formed by her access to resources, “cash transfers,” and the prevailing values/traditions in the society, observed as exogenous factors.

3 Overview of BISP

Almost one-third of the population of Pakistan lives in abject poverty. In 2008, the country witnessed a major shift in its poverty reduction policy and announced the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) as its main social safety-net program. The BISP provides unconditional cash payments and is piloting conditional cash transfers. The unconditional cash transfer provides money directly to the female heads of poor households. The transfer is paid every quarter using automated payment mechanisms like debit card and mobile phone transfers. The program has three main policy goals: (1) eradicating extreme and chronic poverty; (2) empowering women; and (3) achieving universal primary education. The intention is to achieve the first goal through regular cash transfers and the second goal by giving the transfers to women. The government launched a separate conditional cash transfer program in 2013 to increase primary school enrollments.

Getting BISP benefits is contingent upon recipients having a computerized national identity card. While establishing the BISP scheme, an effort was focused on creating a modern, well-managed, large-scale, efficiently targeted cash transfer program. This flagship operation has successfully scaled up to its current coverage of almost 5.6 million families across all provinces, representing about 18 percent of the population of Pakistan. The selection of BISP beneficiaries is made through a poverty scorecard survey based on household demographics, assets, and other measurable characteristics that, in principle, cannot be manipulated by beneficiaries and the survey firms. During the period under analysis for this paper (2015–2016), the benefit level was PKR 1500 per month (~ US $10), paid in quarterly installments. This is enough to provide a monthly supply of wheat flour for a family of six. BISP is also piloting conditions-based cash transfers and is providing assistance to disabled and calamity-stricken communities across the country.

4 Empirical strategy

4.1 The dataset

The BISP has been targeted using a proxy means test (PMT), which is used to attempt to reach 15 percent of households nationwide with regular, unconditional cash transfers. The national targeting mechanism based on PMT was developed in 2010–11. Weights for the PMT were developed using the 2007/8 Pakistan Living Standards Measurement Survey, and the PMT uses 23 variables to compile a poverty score. To target the BISP, a poverty scorecard survey was initiated in 2010/11, collecting information on those 23 variables across Pakistan. Upon completion of the data collection, a PMT score was generated for every household. A PMT threshold (cut-off score) of 16.17 was established based on budget availability to reach at least poorest 15 percent of the population of Pakistan.

Our dataset is derived from the BISP Impact Evaluation Survey 2015–16. This is a nationally and provincially representative survey that collects data on BISP-eligible households in the four target provinces (Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or KPK, and Baluchistan). The sample was chosen to be representative of households in the four provinces that are close to the pre-determined poverty threshold of 16.17. The evaluation sample was created with the intention of exploiting the eligibility criterion to provide a sample including “control” and “treatment” groups. Thus, the evaluation sample has beneficiaries as well as comparable non-beneficiaries. In addition, for ever-married women, the survey gathers information concerning the spouse’s education and age, decision-making outcomes, attitudes toward gender roles, children education, and healthcare, as well as the woman’s labor force participation, control of earnings, and expenditures. As our study is concerned with the appraisal of women’s empowerment regarding herself, familial life choices, and economic choices, the sample we consider includes all ever-married women.

Treatment households are defined as those households with PMT scores equal to and below the cut-off score of 16.17 who received the BISP payment. Control households are defined as those households with a PMT score greater than the cut-off score of 16.17 and within a pre-determined range up to a score of 21.17. Respective samples of treatment and control households were chosen from within each primary sampling unit (PSU) using simple random sampling. This leads to a final sample size of 6447 women, where 3,939 are BISP beneficiaries (~ 61%) and 2,472 (~ 39%) are in the control group.

By limiting the control households to have PMT scores close to but above the threshold of 16.17, it is hoped that factors that affect women’s empowerment, other than the BISP payment, will have low variability between the control and treatment groups. In this sense, the sample may behave similarly to one in which the treatment was randomly allocated. Table 1 presents evidence that this has not been entirely successful.

The second and third columns of Table 1 present the mean values of the observable characteristics for the control and treatment groups, respectively. The fourth column of Table 1 presents p values corresponding to the null hypotheses that each of the variables has identical expected values in the control and treatment groups. These were computed by regressing each of the characteristics on a treatment dummy variable and computing t-statistics using the heteroscedasticity-consistent covariance matrix of White (1980). Since there are 30 different hypotheses, standard hypothesis testing procedures that control the probability of false rejection for a single hypothesis are likely to result in a number of spurious rejections. To avoid this problem, we adjust the p values of the tests using the step-wise multiple testing procedure of Holm (1979). Holm’s procedure provides strong control of the family-wise error rate. Thus, for example, if we reject the null hypothesis in each case for which the adjusted p value is less than 0.05, then the probability of rejecting at least one true null hypothesis is less than 0.05, for any combination of true and false null hypotheses.

Note that, even though the sample was drawn from households with a narrow range of PMT scores, there exists evidence in Table 1 of systematic differences between the treatment and control groups. However, while these differences are statistically significant, they are not economically significant. For example, there exists strong evidence that the mean age of the head of the household is higher in the treatment group than the control group. While it is possible that an age difference that was measured in decades would have important implications for women’s empowerment, the measured difference in Table 1 is slightly less than one year, and it is implausible that such a small difference could have a meaningful impact on women’s empowerment. Similar arguments exist for the other statistically significant variables in Table 1. Consequently, it is reasonable to conclude that differences in women’s empowerment between the treatment and control groups are due to the treatment effect, rather than the small differences in the measurable characteristics of control and treatment groups. Nonetheless, in our empirical work, we include some of the statistically significant variables from Table 1 as control variables in order to ensure that any measured differences in empowerment between the control and treatment groups are not actually due to those variables rather than the BISP payment.

4.2 Variable selection

Our empirical model is designed to measure the impact of the receipt of the BISP payments on the three dimensions of empowerment discussed in Sect. 2—the ability of a woman to act as an individual (“self”), the ability to make choices about children (“familial”), and the ability to participate in the labor force and make decisions about household purchases and investments (“economic”). This task is complicated by the fact that these aspects of empowerment are not directly observable but are instead reflected in the living circumstances of women, as revealed in the Impact Evaluation Survey. In particular, the “economic” aspect of empowerment is reflected by the ability of a woman to make joint decisions with her husband about minor household purchases, lending and borrowing money, making small investments, and the type of work that she does. The “familial” aspect of empowerment is reflected in the woman's ability to make joint decisions with her husband about methods of contraception, having more children, and choices about the education and marriages of their children. The “self” aspect of empowerment is reflected in the ability of a woman to go to the market, to visit friends and neighbors, religious places, and health facilities, and to make joint decisions with her husband about social participation, voting, and serious health problems. We show below that the possession of data on these variables is sufficient to statistically identify the three aspects of empowerment, their mutual correlation, and the impact that receipt of the BISP payment has on each of them individually.

The names of the variables used in the model are listed in Table 2, along with a short functional description and an indication of whether the variable is latent and/or binary. In Appendix Table 6, we provide the empowerment-related questions from the BISP Impact Evaluation Survey Questionnaire.

4.3 The model

In this paper, we propose a latent variable model that reflects two characteristics of empowerment. Firstly, empowerment is not directly observable. Instead, it may be inferred from several observable indicators (Ballon 2018). Secondly, empowerment is a multidimensional process, and a single variable cannot explain all the underlying concepts (Malhotra et al. 2002; Samman and Santos 2009). Nonetheless, the dimensions of empowerment are likely to be mutually correlated.

Let \(f_{i} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {self_{i} } & {familial_{i} } & {economic_{i} } \\ \end{array} } \right)^{\prime}\) be a 3 × 1 vector that measures the three domains of women’s empowerment for person i. Self denotes the individual or self-choice, while familial and economic refer to familial and economic choices (See Sect. 2 for the details). Without loss of generality, we will assume that these variables have means of zero. We would like to estimate the following regression equations.

where \(treat_{i}\) is a dummy variable that indicates whether individual i is part of the treatment group (i.e., is a BISP recipient), \(x_{i}\) is a qx1 vector of control variables, \(\varepsilon_{i}\) is a 3 × 1 vector of potentially mutually correlated unobservable disturbances, \(\beta\) is a 3 × 1 vector of regression coefficients, and \({\Gamma }\) is a 3xq matrix of regression parameters. In Table 1 in Sect. 4.1, we present evidence of small systematic differences between the treatment and control groups. In order to ensure that these do not result in spurious findings about the impact of BISP payments on empowerment, we specify

We stress that our inclusion of these variables is motivated by a desire to minimize any potential correlation between \(treat_{i}\) and \(\varepsilon_{i}\), rather than a direct interest in their relationship with \(f_{i}\).

If \(f_{i}\) was directly observable, then the estimation of, and tests of hypotheses about \(\beta\) would be a standard regression problem. The fact that \(f_{i}\) is latent complicates matters. To resolve this issue, we specify the following confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model for \(f_{i}\):

where \(\xi_{i}\) is a px1 vector of random disturbances, \(\Lambda\) is a px3 full column-rank matrix of coefficients, and \(y_{i}^{*}\) is a px1 vector of latent variables. Denote the elements of \(y_{i}^{*}\) as \(y_{ij}^{*}\), j = 1,…,p. For each \(y_{ij}^{*}\), there exists a latent threshold \(\tau_{j}\) and an observable binary variable \(y_{ij}\) such that

The elements \(y_{ij}\), j = 1,…,p indicate the observable binary responses of individual i to a range of questions intended to measure women’s empowerment. Specifically, we set:

yi = (mobility_marketi mobility_healthi mobility_friendsi mobility_religousi health_problemsi social_participationi votingi another_childi childrens_educi childrens_marriagei family_planningi minor_purchasesi job_choicei lending_borrowingi investmenti)/.

Equation (2) may be rewritten as

where \(K = \left( {\Lambda^{\prime}\Lambda } \right)^{ - 1} \Lambda^{\prime}\) and \(\eta_{i} = - \left( {\Lambda^{\prime}\Lambda } \right)^{ - 1} \Lambda^{\prime}\xi\). Together, Eqs. (1) and (3) constitute a Structural Equation Model (SEM).

Note that, for any 3 × 3 matrix \(M\), we may write

where \(\tilde{K} = MK\), \(\tilde{\eta }_{i} = K\eta_{i}\), and \(\tilde{f}_{i}\) is an observationally equivalent representation of the latent women’s empowerment variables. In this sense, in general, the SEM is not identified. Fortunately, our application provides restrictions that are sufficient to resolve this issue. Note that each of the elements of \(y_{i}\) loads onto only a single factor. In particular, mobility_market, mobility_health, mobility_friends, mobility_religous, health_problems, social_participation, and voting are related to only the “self” component of women’s empowerment; another_child, childrens_educ, childrens_marriage, and family_planning are related to only the “familial” component; and minor_purchases, job_choice, lending_borrowing, and investment are related to only the “economic” component. Thus, for an appropriately ordered vector \(y_{i}^{*}\), \(\Lambda\) is block diagonal, consisting of three blocks, each of which is a column vector. It follows that \(K\) is a block diagonal matrix, consisting of three blocks, each of which is a row vector. The only values of \(M\) that respect this structure are diagonal matrices. Thus, \(f_{i}\) is identified up to a rescaling of the elements. To resolve the indeterminate scaling, we (arbitrarily) set the variances of the elements of \(f_{i}\) to 1. Note that there exist other variables that might be included in \(y_{i}\). Examples include attitudes to IPV and the ability of the woman to express an opinion. However, the addition of such variables complicates arguments about identification since, unlike the variables that we have included in \(y_{i}\), they are not associated with only a single element of \(f_{i}\).

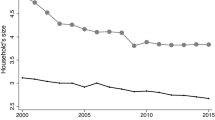

The model is represented diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

5 Results and discussion

The model described in the previous section was estimated using the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) procedure implemented in the Lavaan package for the R programming language.Footnote 21

Table 3 shows the estimated covariance matrix for the three aspects of women’s empowerment. Also shown are the t-statistics corresponding to the null hypotheses that each of the elements of the covariance matrix is equal to zero. Recall that the variances of the empowerment variables are unidentified and have been arbitrarily set to unity.

As might be expected, the aspects of women’s empowerment are positively correlated with each other. The large t-statistics provide strong evidence against the hypotheses that the correlations are zero. Note that the correlation between the “economic” and “familial” aspects of women’s empowerment is stronger than that between the “self” aspect and either of the other two aspects. Nonetheless, the fact that none of the correlations are particularly close to 1 supports the proposition that women’s empowerment needs to be understood as a multidimensional concept.

Table 4 shows the estimates of the elements of \(K\). As discussed above, \(K\) is block diagonal due to the restrictions implied by the elements of \(y_{i}\). Note that, for the “self” aspect of empowerment, the largest loadings are on the mobility variables, with joint decisions about social participation, serious health problems, and voting having a less strong relationship with “self.”

For the “familial” aspect of empowerment, each of the variables is approximately equally important. For the “economic” aspect of empowerment, joint decisions about lending and borrowing and small investments are the most important variables. As might be expected, all the elements of \(K\) are positive. They are also all highly statistically significantly different from zero. For completeness, Table 4 also includes the values of the estimated thresholds, \(\tau_{j}\), j = 1,…,p.

Finally, in Table 5, we present the estimates of \(\beta\) and \(\Gamma\).

Note that there exists evidence that some of the control variables have a statistically significant relationship with some of the aspects of women’s empowerment. Thus, the fact that there are some differences in the characteristics of the treatment and control groups beyond the receipt of the BISP payment (as illustrated in Table 1) is a relevant consideration. However, the estimated coefficients for the control variables are generally quite small. This, combined with the fact that these variables differ by only a small amount between the treatment and control groups, as established in Table 1, supports our conjecture that these variables account for little variation in women’s empowerment between those households in the sample that receive the BISP payment and those that do not. Controlling for these variables, we find that the relationship between the receipt of the BISP payment and each of the three aspects of women’s empowerment is positive and statistically significantly different from zero. A Wald test of the null hypothesis that each of the elements of \(\beta\) is jointly equal to zero, so that the BISP payment has no impact on women’s empowerment, returns a test statistic of 21.335. Since the statistic has a \(\chi_{3}^{2}\)-distribution, the null hypothesis is strongly rejected at any conventional significance level. Note that the estimated impact of the BISP payment on the “self” aspect of empowerment is ~ 37% higher than that of the impact on the “familial” and “economic” aspects. A Wald test of the null hypothesis that the BISP payment has an equal impact on each of the three aspects of empowerment generates a test statistic of 18.158. Under the null hypothesis, such statistics have a \(\chi_{1}^{2}\)-distribution. Consequently, the differences in the estimates of the impact are highly statistically significant. This extends the result of previous studies measuring women’s empowerment in Pakistan including Akram (2018), Chaudhry and Nosheen (2009), and Ghuman et al. (2006), which found that women have greater decision outcomes concerning their self-domain compared to the familial or the economic choice domain, specifically in the treatment group.

The results of Table 5 report evidence that the BISP-targeted cash transfer program in Pakistan has wide-ranging impacts on the lives of beneficiaries beyond the intended scope as a poverty reduction intervention. Our results demonstrate that the transfer was successful in improving multidimensional agency and decision-making of women and that these effects were robust to various measures of women’s agency in various domains of their lives. While the existing literature hypothesizes that economic development/poverty alleviation by itself cannot ensure significant achievements in women’s empowerment (see Duflo 2012 in this respect), our results provide reasonably strong evidence that the BISP transfer has indeed had successful impacts on women’s empowerment. Giving cash, even small but regular amounts, to women appears to have significantly impacted all three aspects of empowerment we studied in this research.

Our results in Tables 4 and 5 indicate that BISP is a crucial determinant of self-choices that lead to improvement in female mobility, healthcare, social participation, and voting. This means participation in the program relaxes some of the norms like “freedom of mobility” and “meeting with non-relatives of the family” for the female participants. Mobility remains the most important and widely used indicator of socio-cultural empowerment in the literature. Jayachandran (2021a, b) noted that the practice of “purdah” in Islam (which is also the religious faith in Pakistan) enhances the low employment rate in the Middle East and North Africa [see also Koomason’s (2017) study on Ghana]. Several researchers declared that advancement in women’s liberty of mobility is essential for increasing their capacity to make personal choices, adjust their behaviors, expand their public linkages, attain better employment, and lessen their state of poverty (D’Acci 2011; Gram et al. 2019).

Women’s awareness of their and their partner’s roles is an important component of women’s empowerment. Our findings show that the husband’s support in joint decision-making is a significant determinant of women’s empowerment in the domains of familial, economic, and some aspects of self-choices. Our results are in line with those of Khan and Awan (2011) and Batool et al. (2019) in that husbands’ support and co-operation have statistically significant effects on women’s empowerment. When a husband provides support to his wife by setting a cordial relationship and allowing her the freedom to express her state of mind and helps her resolve her problems, she may feel protected and consequently gain confidence.

As seen in Table 4, the indicator “job_choice” has a statistically significant relationship with the economic aspect of women’s empowerment. When women are allowed to work outside the family, they gain greater freedom in making choices which in turn affects their own health and mobility, important economic matters, and the education of their children. The women that BISP targets are the poorest of the poor in Pakistan. These women are not in paid employment but work as farm helpers for their landlords or husbands—most of these women work for food and clothing and are unable to make even small purchases. This also has huge implications for the success of cash transfer programs in impacting empowerment. Women who have capacity to make decisions may keep control of the cash transfer and use the money to improve the health and education status of their family. Similarly, if a woman has a say in minor household purchases, it is more likely that she will spend the money on improving her child's nutritional outcomes. Our economic choice outcome also includes the investment and borrowing choices of women. In the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, Field et al. (2020) noted that when women have a bank account, their labor force participation rate increases. Schaner's (2011) case study in Kenya makes the same conclusion. Jayachandran (2021a, b) considers this as the change in social norms toward better women’s empowerment.

Note that BISP beneficiary status has a positive impact on the “familial” aspect of women’s empowerment, indicating that BISP transfers influence such decisions as family planning, increasing family size, and, most importantly, children’s education. This is a critical finding that could have important implications for Pakistan with the world’s second-highest number of out-of-school children (OOSC). An estimated 22.8 million children in Pakistan aged 5–16 do not attend school, which represents 44 percent of the total population in this age group. Therefore, BISP can play a critical role in promoting education through its unconditional as well as conditional cash transfer programs. Ashraf et al. (2010) noted in the case of Zambia that women try to hide their family planning decision from their husbands. Our results show improvement of women’s empowerment of the BISP beneficiaries’ joint decision-making in family planning despite the presence of a strong cultural norm against this.

Our analysis of empowerment and the role of cash transfers in improving empowerment also suggests that it is the cash that influences the wider behavioral changes reported, without any conditions imposed on women, contradicting the idea that only cash that comes with conditions brings changes within households leading to the supposed empowerment of women (Adato et al. 2000).

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we present a model of women’s empowerment for the BISP target population in Pakistan. We define empowerment as the ability of a woman to make decisions related to self, familial, and economic choices, and we use this definition in the specific context of women as beneficiaries of poverty alleviation programs. We distinguish three key elements that contribute to a woman’s ability to make such decisions, as theorized by Kabeer (1999): her enabling resources; decision outcomes as a measure of her agency; and values/traditions as a measure of the settings or pre-conditions. Based on this definition, this paper presents a structural equation model, to measure and explain the causes of women’s empowerment. Our measurement model confirms that women’s empowerment is indeed a multidimensional construct. The results of the structural model reveal the importance of providing cash transfers to the woman of the house at all three dimensions of empowerment. Specifically, the treatment group communities are more likely to report that they can visit friends, market, health facilities, and religious places without permission. Furthermore, they can make joint decisions on serious health-related issues, social participation, and participation in voting in elections. However, their voice is less pronounced compared to the above indicators in familial (children marriage and education, as well as family planning) and economic (household purchase, investment, etc.) dimensions.

Based on these results, various policy implications can be put forward. The first is that cash transfers without conditions may help to alter behavioral patterns, but choices related to various socio-economic norms are much harder to change. BISP can initiate small Community Leaders forums, at the level of village and at the Tehsil,Footnote 22 to generate discussion and peer learning practices for a better understanding of the rights and obligations of women. Materials providing education about women’s rights can also be distributed to promote awareness. Further participatory research is needed to explore this phenomenon.

Secondly, there is clear evidence that BISP has the potential to assist women by addressing their needs and enhancing their capacity for economic, social, and personal development. But to fully capitalize on this opportunity, it is important for BISP and similar interventions to mainstream gender practices that uplift the status of women not only within households but also in society at large. For instance, women beneficiary representatives should be included in important policy formulation processes at various administrative and operations levels of BISP Boards to provide recommendations for promoting gender equity. Therefore, more gender-sensitive design features in BISP or any other cash transfer programs in the developing world in general are required to reduce poverty and help governments advance their goals of achieving greater gender equality.

Notes

The Goal 5 of United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) refers to the achievement of gender equality and empower all women and girls (https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals and https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/).

For example, girls’ primary and secondary enrollment, female labor force participation rates, time spent doing domestic/household chores, number of physical/psychological abuses by family members/partner, etc.

All three models are starkly different from the approach of Ganle et al. (2015) who built a multidimensional women empowerment model qualitatively to evaluate an NGO-run micro-lending program in Ghana. Similarly, the qualitative research by Broady et al. (2016) estimates effects of Self-Help Group Programs on economic and political empowerment, women’s mobility, and women’s control over family planning, as well as familiarity in handling money, independence in financial decision-making, solidarity, social networks, and respect from the household and other community members.

Ambler and De Brauw (2017) analyzed impacts of BISP on selected indicators of women’s empowerment using a regression discontinuity design (RDD) methodology and data from the 2013 round of the BISP Impact Evaluation Survey. They found that there is a significant positive impact on women’s mobility. Overall, their study suggests small positive impacts toward women’s empowerment where women are less likely to tolerate being beaten, and men are more likely to agree that they should be expected to help around the house. Women also become more likely to report that they can visit friends without permission, and they become more likely to vote. Iqbal et al. (2020) empirically quantified women’s empowerment through dimensions centered on gender norms, women’s autonomy/mobility, and the socio-economic and political empowerment of women. They found that BISP had positive and significant impacts on women’s socio-economic and political empowerment and mobility in 2016, while the study found no significant impact in improving gender norms with men’s perspective. Waqas and Awan (2019a, b) explored impacts of the BISP cash transfer on women’s empowerment using primary data of 1000 beneficiaries in Punjab province of Pakistan. They found positive impacts of cash transfers on women’s decision-making within households.

Baranov et al. (2020) in their cluster RCT-based maternal health study on Pakistan used a multidimensional idea of women empowerment. Our constructed dimensions of empowerment in relation to the BISP beneficiaries are different from their study. Recently, in a study on India, Dhar et al. (2022) used the RCT method with an intervention engaging adolescent girls and boys in classroom discussions about gender equality for two years. A positive effect of the program in attitudes toward more supportive of gender equality was observed in their results.

See Bastagli et al. (2016) for the discussion of potential negative consequences of unconditional cash transfer programs. Also see https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/tools-resources/evidence-based-resource/unconditional-cash-transfers-for-reducing-poverty-and

In a different context for India, Roy (2015) examined the impact of gender-progressive reforms to the inheritance law on women’s outcome and showed the possibility of evolution of social norms.

See Table 6 in the Appendix.

the sub-district administration unit in Pakistan where a BISP presence is maintained.

References

Abreha SK, Walelign SZ, Zereyesus YA (2020) Associations between women’s empowerment and children’s health status in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0235825. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235825

Acharya DR, Bell JS, Simkhada P, Van Teijlingen ER, Regmi PR (2010) Women’s autonomy in household decisionmaking: a demographic study in Nepal. Reprod Health 7(1):15

Acharya M, Bennett L (1982) Women and the subsistence sector. Economic participation and household in Nepal. World Bank Staff Working Papers, 526. World Bank. Washington DC. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/905581468775579131/pdf/multi0page.pdf

Adato M, De la Briere B, Mindek D, Quisumbing A (2000) The impact of PROGRESA on women’s status and intrahousehold relations. Final Report, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington

Agarwal B (1994) A field of one's own: Gender and land rights in South Asia, vol 58. Cambridge University Press

Aker JC, Boumnijel R, McClelland A, Tierney N (2016) Payment mechanisms and antipoverty programs: evidence from a mobile money cash transfer experiment in Niger. Econ Dev Cult Change 65(1):1–37

Alderman H, Gertler P (1997) Family resources and gender differences in human capital investments: The demand for children’s medical care in Pakistan. In: Haddad L, Hoddinott J, Alderman H (eds) Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries: Models, Methods and Policy. International Food Policy Research Institute: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, pp 231–248. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/127320/filename/127531.pdf

Alkire S (2007) Choosing dimensions: the capability approach and multidimensional poverty. In: The many dimensions of poverty. Springer, pp 89–119

Alkire S (2008) Concepts and measures of agency. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI). OPHI Working Paper 09. https://ophi.org.uk/sites/default/files/OPHIwp09.pdf

Allendorf K (2007) Do women’s land rights promote empowerment and child health in Nepal? World Dev 35(11):1975–1988

Alsop R, Bertelsen M, Holland J (2005) Empowerment in practice: from analysis to implementation. The World Bank

Anderson S, Eswaran M (2009) What determines female autonomy? Evidence from Bangladesh. J Dev Econ 90(2):179–191

Angelucci M, Karlan D, Zinman J (2015) Microcredit impacts: Evidence from a randomised microcredit program placement experiment by Compartamos Banco. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):151–182

Ashraf N (2009) Spousal control and intra-household decision making: an experimental study in the Philippines. Am Econ Rev 99(4):1245–1277

Aslam M, Kingdon GG (2008) Gender and household education expenditure in Pakistan. Appl Econ 40(20):2573–2591

Attanasio O, Lechene V (2002) Tests of income pooling in household decisions. Rev Econ Dyn 5(4):720–748

Ambler K, De Brauw A (2017) The impacts of cash transfers on women’s empowerment: learning from Pakistan’s BISP program. Policy Research Working Paper Series 113161, The World Bank

Bahadir-Yilmaz E, Öz F (2018) The effectiveness of empowerment program on increasing self-esteem, learned resourcefulness, and coping ways in women exposed to domestic violence. Issues Ment Health Nurs 39(2):135–141

Baird S, Özler B (2016) Sustained effects on economic empowerment of interventions for adolescent girls: existing evidence and knowledge gaps. CGD background paper. Center for Global Development, Washington

Ballon P (2018) A structural equation model of female empowerment. J Dev Stud 54(8):1303–1320

Bandiera O, Buehren N, Burgess R, Goldstein M, Gulesci S, Rasul I, Sulaiman M (2020) Women’s empowerment in action: evidence from a randomised control trial in Africa. Am Econ J Appl Econ 12(1):210–259

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Glennerster R, Kinnan C (2015) The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomised evaluation. Am Econ J Appl Econ 7(1):22–53

Baranov V, Bhalotra S, Biroli P, Maselko J (2020) Maternal depression, women’s empowerment, and parental investment: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Am Econ Rev 110(3):824–859

Baranov V, Cameron L, Contreras Suarez D, Thibout C (2021) Theoretical underpinnings and meta-analysis of the effects of cash transfers on intimate partner violence in low- and middle-income countries. J Dev Stud 57(1):1–25

Batool SA, Batool SS, Kauser S (2019) Do personal and familial factors matter in women's familial empowerment? A logistic model. Paradigm 13(2). https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA630858726&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=19962800&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7Ef34a0cb1

Behrman JR (1997) Intrahousehold distribution and the family. Handb Popul Fam Econ 1:125–187

Bollen KA (1989) A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res 17(3):303–316

Braaten RH, Martinsson P (2015) Experimental measures of household decision power. https://www.frisch.uio.no/prosjekter/cree/publications/CREE_working_papers/pdf_2015/braaten_martinsson_houshold_decision_power_cree_wp02_2015.pdf

Brody C, Hoop TD, Vojtkova M, Warnock R, Dunbar M, Murthy P, Dworkin SL (2017) Can self-help group programs improve women’s empowerment? A systematic review. J Dev Effect 9(1):15–40

Bursztyn L, Gonzalez AL, David Yanagizawa-Drott D (2020) Misperceived social norms: women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia. Am Econ Rev 110(10):2997–3029

Carlsson F, He H, Martinsson P, Qin P, Sutter M (2012) Household in rural China: using experiments to estimate the influences of spouses. J Econ Behav Organ 84(2):525–536

Chakrabarti S, Biswas CS (2012) An exploratory analysis of women’s empowerment in India: a structural equation modelling approach. J Dev Stud 48(1):164–180

Chaudhuri K, Yalonetzky G (2018) The state of female autonomy in India: a stochastic dominance approach. J Dev Stud 54(8):1338–1353

Chen M (1992) Conceptual model for women’s empowerment. International Center for Research on Women

Chung W, Gupta MD (2007) The decline of son preference in South Korea: the roles of development and public policy. Popul Dev Rev 33(4):757–783

Cornwall A (2016) Women’s empowerment: What works? J Int Dev 28(3):342–359

D’Acci L (2011) Measuring well-being and progress. Soc Indic Res 104:47–65

De Brauw A, Gilligan DO, Hoddinott J, Roy S (2014) The impact of Bolsa Família on women’s decisionmaking power. World Dev 59:487–504

Dhar D, Jain T, Jayachandran S (2022) Reshaping adolescents’ gender attitudes: evidence from a school-based experiment in India. Am Econ Rev 112(3):899–927

Doss, (2013) Intrahousehold bargaining and resource allocation in developing countries. World Bank Res Obser 28(1):52–78

Duflo E (2003) Grandmothers and granddaughters: old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Econ Rev 17(1):1–25

Duflo E (2012) Women empowerment and economic development. J Econ Lit 50(4):1051–1079

Eswaran M (2002) The empowerment of women, fertility, and child mortality: towards a theoretical analysis. J Popul Econ 15(3):433–454

Field E, Pande R, Rigol N, Schaner S, Moore CT (2020) On her own account: how strengthening women's financial control impacts labor supply and gender norms, Working paper, Yale University

Gammage S, Kabeer N, van der Meulen Rodgers Y (2016) Voice and agency: Where are we now? Fem Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1101308

Ganle JK, Afriyie K, Segbefia AY (2015) Microcredit: empowerment and disempowerment of rural women in Ghana. World Dev 66(C):335–345

Ghuman SJ (2003) Women’s autonomy and child survival: a comparison of Muslims and non-Muslims in four Asian countries. Demography 40(3):419–436

Ghuman SJ, Lee HJ, Smith HL (2006) Measurement of women’s autonomy according to women and their husbands: results from five Asian countries. Soc Sci Res 35(1):1–28

Gram L, Skordis-Worrall J, Saville N, Manandhar DS, Sharma N, Morrison J (2019) ‘There is no point giving cash to women who don’t spend it the way they are told to spend it’—exploring women’s agency over cash in a combined participatory women’s groups and cash transfer programme to improve low birthweight in rural Nepal. Soc Sci Med 221:9–18

Haddad L, Hoddinott J (1994) VDoes female income share influence household expenditures. Evidence from Cote doIvoire. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 57(1):77

Handa S, Davis B (2006) The experience of conditional cash transfers in Latin America and the Caribbean. Dev Policy Rev 24(5):513–536

Handa S, Peterman A, Davis B, Stampini M (2009) Opening up Pandora’s box: The effect of gender targeting and conditionality on household spending behavior in Mexico’s PROGRESA program. World Dev 37(6):1129–1142

Haque M, Islam TM, Tareque MI, Mostofa M (2011) Women empowerment or autonomy: a comparative view in Bangladesh context. Bangladesh e-J Sociol 8(2):17–30

Haushofer J, Ringdal C, Shapiro JP, Wang XY (2019) Income changes and intimate partner violence: evidence from unconditional cash transfers in Kenya. NBER Working Paper 25627. http://www.nber.org/papers/w25627

Hoddinott J, Haddad L (1995) Does female income share influence household expenditures? Evidence from Côte d’Ivoire. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 57(1):77–96

Holm S (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70

Iqbal T, Padda IU, Farooq S (2020) unconditional cash transfers and women empowerment: the case of Benazir income support programme (BISP) in Pakistan. J Bus Soc Rev Emerg Econ. https://doi.org/10.26710/jbsee.v6i2.1098

Jayachandran S (2021a) Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries. IMF Econ Rev 69(3):576–595

Jayachandran S (2021b) “Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries,” IMF Economic Review, Palgrave Macmillan. Int Monet Fund 69(3):576–595

Jejeebhoy SJ (2002) Convergence and divergence in spouses’ perspectives on women’s autonomy in rural India. Stud Fam Plann 33(4):299–308

Jejeebhoy SJ, Sathar ZA (2001) Women’s autonomy in India and Pakistan: the influence of religion and region. Popul Dev Rev 27(4):687–712

Koomson E (2017) Transforming customary system in Ghana: women's participation in small-scale gold mining activities in the Talensi District. PhD thesis, University of Michigan

Kabeer N (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Chang 30(3):435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

Kabeer N (2001) Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment’in Discussing Women’s Empowerment—theory and practice. Sida Studies No. 3. Stockholm: Novum Grafiska AB

Khan SU, Awan R (2011) Contextual assessment of women empowerment and its determinants: Evidence from Pakistan. MPRA Paper 30820, University Library of Munich, Germany

Khan TM, Maan AA (2008) Socio-cultural milieu of women’s empowerment in district Faisalabad. Pak J Agri Sci 45(3):78–90

Kinyondo AA, Ntegwa MJ (2023) The impact of cash transfers on intimate partner violence: a quasi-experimental evidence from Tanzania. Afr Rev 1(aop):1–22

Kishor S (2000) Empowerment of women in Egypt and links to the survival and health of their infants. International Union of Scientific Study of Population

Malhotra A, Mather M (1997) Do schooling and work empower women in developing countries? Gender and domestic decisions in Sri Lanka. Sociol Forum 12:599–630. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:141395256

Malhotra A, Schuler SR (2005) Women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. Meas Empower: Cross-Discipl Perspect 1:71–88

Malhotra A, Schuler SR, Boender C (2002) Measuring women’s empowerment as a variable in international development. Paper presented at the background paper prepared for the World Bank Workshop on Poverty and Gender: New Perspectives

Mason KO, Smith HL (2003) Women’s empowerment and social context: Results from five Asian countries. Gender and Development Group, World Bank, Washington, DC

Miedema SS, Shwe S, Kyaw AT (2016) Social inequalities, empowerment, and women’s transitions into abusive marriages: a case study from Myanmar. Gend Soc 30(4):670–694

Miedema SS, Haardörfer R, Girard AW, Yount KM (2018) Women’s empowerment in East Africa: development of a cross-country comparable measure. World Dev 110:453–464

Muralidharan K, Nishith P (2017) Cycling to school: increasing secondary school enrollment for Girls in India. Am Econ J Appl Econ 9(3):321–350

Muthén B (1984) A general structural equation model with dichotomous, ordered categorical, and continuous latent variable indicators. Psychometrika 49(1):115–132

Narayan D, Pritchett L, Kapoor S (2009) Moving out of poverty, volume 2: success from the bottom up. The World Bank

Nussbaum M (2000) Women’s capabilities and social justice. J Hum Dev 1(2):219–247

Patel L, Knijn T, Van Wel F (2015) Child support grants in South Africa: a pathway to women’s empowerment and child well-being? (report) (author Abstract) 44(2):377

Peterman A, Schwab B, Roy S, Hidrobo M, Gilligan DO (2015) Measuring women's decision making: indicator choice and survey design experiments from cash and food transfer evaluations in Ecuador, Uganda, and Yemen

Pitt MM, Khandker SR, Cartwright J (2006) Empowering women with micro finance: evidence from Bangladesh. Econ Dev Cult Change 54(4):791–831

Quisumbing AR, de La Brière B (2000) Women's assets and intrahousehold allocation in rural Bangladesh: testing measures of bargaining power: International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/.

Rigdon EE (1995) A necessary and sufficient identification rule for structural models estimated in practice. Multivar Behav Res 30(3):359–383

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48(2):1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Roy S (2015) Empowering women? Inheritance rights, female education and dowry payments in India. J Dev Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.12.010

Said F, Mahmud M, d’Adda G, Chaudhry A (2019) Home-bias among female entrepreneurs: experimental evidence on preferences from Pakistan. Centre for Research in Economics and Business (CREB). https://creb.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CREB-Working-Paper-04-20.pdf

Saleem S, Bobak M (2005) Women’s autonomy, education and contraception use in Pakistan: a national study. Reprod Health 2(8):1–8

Samman E, Santos ME (2009) Agency and empowerment: a review of concepts, indicators and empirical evidence. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI). https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:974e9ca9-7e3b-4577-8c13-44a2412e83bb

Sathar ZA, Kazi S (2000) Women's autonomy in the context of rural Pakistan. Pak Dev Rev 39(2):89–110

Schuler SR, Hashemi SM (1993) Defining and studying empowerment of women: a research note from Bangladesh. Sociol. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:148976764

Schuler SR, Hashemi SM (1994) Credit programs, women's empowerment, and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plan 25(2):65–76

Sen A (1985) Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. J Philos 82(4):169–221

Sen A (1989) Women’s survival as a development problem. Bull Am Acad Arts Sci 43(2):14–29

Sen A (1999) Commodities and capabilities. OUP Catalogue

Sen A (2001) Development as freedom: Oxford Paperbacks

Shibata R, Cardey S, Dorward P (2020) Gendered intra-household decision-making dynamics in agricultural innovation processes: assets, norms and bargaining power. J Int Dev 32:1101–1125

Tareque M, Haque M, Mostofa M, Islam T (2007) Age, age at marriage, age difference between spouses & women empowerment: Bangladesh context. Middle East J Age Ageing 4(6):8–14

Waqas M, Awan MS (2019a) Do cash transfers effect women empowerment? Evidence from Benazir Income Support Program of Pakistan. Women’s Study 48(7):777–792

Waqas M, Awan MS (2019b) Do cash transfers effect women empowerment? Evidence from benazir income support program of Pakistan. Women Stud 48(7):777–792

White H (1980) A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometr: J Econometr Soc 48(4):817–838

Winkvist A, Akhtar HZ (2000) God should give daughters to rich families only: attitudes towards childbearing among low-income women in Punjab. Pak Soc Sci Med 51(1):73–81

Yount KM, VanderEnde KE, Dodell S, Cheong YF (2016) Measurement of women’s agency in Egypt: a national validation study. Soc Indic Res 128(3):1171–1192

Yount KM, Crandall AA, Cheong YF (2018) Women’s age at first marriage and long-term economic empowerment in Egypt. World Dev 102(1):124–134

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Chris Heaton, Asma Kashif, and Pundarik Mukhopadhaya. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Asma Kashif, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. The revised draft was written by Chris Heaton and Pundarik Mukhopadhaya. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Appendix Table

6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heaton, C., Kashif, A. & Mukhopadhaya, P. Unconditional cash transfer programs and women’s empowerment: evidence from Pakistan. Empir Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-024-02626-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-024-02626-8