Abstract

Using administrative database containing work history and programme participation for the entire national workforce, the paper evaluates Slovenia’s four main active labour market programmes: institutional training, on-the-job training, wage subsidies and public works. The studied outcomes range from post-unemployment employment probability and job quality to cumulative effects on employment and earnings over the longer run, and also include programmes’ cost-effectiveness. We identify programme effects by comparing outcomes of treatment and control groups using propensity score matching. The results show that the programmes perform rather well judged both by their impact on labour market outcomes and by their cost-effectiveness: except for public works, all programmes are found to have a net benefit in terms of government expenditures. Our results are robust to time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity in the treatment and control groups, as we corroborate the baseline propensity score matching results with a difference-in-difference estimator.

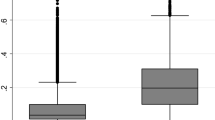

Source: own calculations based on combined ZRSZ/SRDAP/ZPIZ database, SORS

Source: own calculations based on combined ZRSZ/SRDAP/ZPIZ database, SORS

Source: own calculations based on combined ZRSZ/SRDAP/ZPIZ database, SORS

Source: own calculations based on combined ZRSZ/SRDAP/ZPIZ database, SORS

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hourly wages for unemployed workers are set to zero. Such an imputation is unproblematic also for pre-programme wages for the individuals without previous employment, because we impose strict conditionality that first-time jobseekers are matched with controls that also have no job history.

Previous Monte Carlo studies investigating the robustness of various estimators for treatment effects conclude that there is no estimator that performs best in all settings and in relation to all criteria (see Frölich 2004; Huber et al. 2013; Busso et al. 2014). Apart from our preferred method, PSM, we therefore also apply several alternative estimators for robustness checks.

We also tested an alternative approach where we set elapsed time to zero (1) for programme participants at their exit from the programme, and (2) for individuals included in the control group in the month their matching treatment group programme participant entered the programme. Given the relatively long observation period over which we evaluate programme effects, the alternative approach yielded different results in the first year, but virtually identical results over the longer time horizon.

The following variables (all at time τS) are used in the propensity score estimations and designated with L and B superscript when they appear also in Lechner and Wunsch (2013) and Biewen et al. (2014), respectively: genderL,B (dummy variable), ageL,B, current unemployment spell lengthL,B, education levelL,B, set of region dummiesL,B, set of regional offices dummies (to control for office-specific effect to direct individuals to the programme in addition to municipality-specific effect that picks-up variability in geographic sense), unemployment benefit status dummyL,B, Slovene nationality dummyL,B, set of occupation dummiesL,B, disability status dummyL,B, reason for the current unemployment statusL (set of dummy variables), degree of employabilityL (as assessed by employment counsellors at the initial interview), wage level of the most recent employmentL,B prior to τS (0 if no job has been held), deficient education dummy, cumulative length of past employment spellsL,B in years up to τS, number of different past employersL,B up to τS, no previous employment dummyB, excess supply occupations dummy, redundant occupations dummy and a set of month dummiesL,B for each month of programme admission separately. Due to data constraints, we were unable to control for health status (apart from disability status), family and marital status, last employment firm characteristics, industry and occupation-specific experience and characteristics of job looked for. However, Lechner and Wunsch (2013) show that apart from family and marital conditions, other blocks of control variables do not reduce bias significantly enough to be worth investing additional resources.

We distinguish 6 different strata of elapsed unemployment length: 1–6 months, 6–12 months, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, 3–5 years, and more than 5 years.

As a robustness check, we also estimated the effects of the evaluated programmes conditional on controls not joining any other ALMP after the matching period τS. We censor (that is, exclude from the observation set) all individuals at the moment they enter another ALMP. The results—which yield broadly similar results, albeit with slightly larger estimated effects—are available upon request.

Van der Berg and Vikström (2019) provide an alternative approach to dynamically assigned treatments based on the inverse probability treatment estimators where they use as a control group only those individuals who are not treated before leaving unemployment (“never treated”).

The ex-ante quasi-exact-matching procedure may be rather demanding because it is difficult to assure balancing for all covariates within all blocks (Cerulli 2015, p. 81). Moreover, we evaluated propensity score for each year separately and we additionally matched strictly upon 6 distinct variables (gender, region, year-month, first employment dummy, duration of current unemployment spell and occupation), which cannot be taken into account with Stata pstest command.

Additional results on hours worked, provided in Online Appendix 3, broadly corroborate the findings discussed in the main text. The results show a positive impact of programme participation on hours worked in all the studied programmes, except that the effect of public works is limited to the period of programme participation.

We also find that participants of the studied programmes are paid comparable wage rates as workers in the control group and, therefore, it may appear that the treatment effects on the post-unemployment hourly wage of workers who have found jobs are negligible (Figure A3.2, Online Appendix 3). The only notable exception are the negative effects for public works participants during programme participation. However, because here we compare outcomes produced by the selection into employment, comparability of the matched treated and non-treated individuals is compromised and hence these results are subject to the sample selection bias (Heckman 1979). We thank an anonymous referee for pointing out that the causal interpretation of such a conditional comparison is unwarranted.

The segmentation of the Slovenian labour market has been one of the highest in the European Union. In 2011–12—during the implementation of the studied ALMPs—17.5% of workers in Slovenia were employed under fixed-term contracts, compared to the average of 13.5 percent in OECD countries; among European OECD countries, Slovenia’s share lagged only behind Poland, Portugal and Spain (OECD 2014).

According to the Slovenian Employment Relations Act, fixed-term contracts can only last for two years (with rare exceptions).

In results shown in Online Appendix 3, we also examine the effects of the programmes on the first post-unemployment continuous employment spell. The results are qualitatively similar to what is discussed elsewhere in the paper, with the exception of Institutional training, which is shown not to affect the duration of the first post-unemployment continuous employment spell.

Throughout 2009–2014, Slovenia’s public expenditures on ALMPs as well as its participation stocks lagged substantially behind the average for OECD countries. In 2014, for example, Slovenia’s public expenditures on ALMPs amounted to only 0.37% of GDP, trailing strongly behind the average of 0.55% of GDP spent on active programmes by OECD countries; similarly, 1.85% of the Slovenia’s labour force participants took part in ALMPs, compared to 4.11% for the OECD average (OECD 2016).

The programme only modestly improved some of the studied longer-term outcomes, but it apparently achieved its goal of social inclusion of the most disadvantaged unemployed. While the computed net benefit of the programme is negative, this calculation ignores other potential social benefits (reduction of social benefit transfers and health expenditures, and reduction of crime, for example).

References

Becker S, Ichino A (2002) Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. Stand Genomic Sci 2(4):358–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0200200403

Biewen M, Fitzenberger B, Osikominu A, Paul M (2014) The effectiveness of public-sponsored training revisited: the importance of data and methodological choices. J Law Econ 32(4):837–897. https://doi.org/10.1086/677233

Busso M, DiNardo J, McCrary J (2014) New evidence on the finite sample properties of propensity score reweighting and matching estimators. Rev Econ Stat 96(5):885–897. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00431

Card D, Kluve J, Weber A (2018) What works? A meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. J Eur Econ Assoc 16(3):894–931. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028

Cerulli G (2015) Econometric evaluation of socio-economic programs. Adv Stud Theor Appl Econom Ser. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-46405-2

Dehejia R, Wahba S (1999) Causal effects in nonexperimental studies: reevaluating the evaluation of training programs. J Am Stat Assoc 94(448):1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10473858

Frölich M (2004) Finite-sample properties of propensity-score matching and weighting estimators. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):77–90. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465304323023697

Gerfin M, Lechner M (2002) A microeconometric evaluation of the active labour market policy in Switzerland. Econ J 112:854–893

Graversen BK, van Ours JC (2008) How to help unemployed find jobs quickly: experimental evidence from a mandatory activation program. J Public Econ 92(10–11):2020–2035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.04.013

Heckman J (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352

Heckman J, Ichimura H, Smith J, Todd P (1998) Characterizing selection bias using experimental data. Econometrica 66(5):1017–1098. https://doi.org/10.2307/2999630

Huber M, Lechner M, Wunsch C (2013) The performance of estimators based on the propensity score. J Econom 175(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2012.11.006

Imbens GW (2000) The role of the propensity score in estimating dose-response functions. Biometrika 87(3):706–710. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/87.3.706

Lammers M, Kok L (2019) Are active labor market policies (cost-)effective in the long run? Evidence from the Netherlands. Empir Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01812-3

Lechner M, Wunsch C (2013) Sensitivity of matching-based program evaluations to the availability of control variables. Labour Econ 21:111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2013.01.004

OECD (2014) OECD employment outlook 2014. OECD, Paris. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/oecd-employment-outlook-2014_empl_outlook-2014-en

OECD (2015) OECD employment outlook 2015. OECD, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2015-en

OECD (2016) OECD employment outlook 2016. OECD, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2016-en

Rodríguez-Planas N, Benus J (2010) Evaluating active labor market programs in Romania. Empir Econ 38:65–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-009-0256-z

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D (1983) The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70(1):41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Sianesi B (2004) An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labor market programs in the 1990s. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):133–155. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465304323023723

Sianesi B (2008) Differential effects of active labour market programs for the unemployed. Labour Econ 15(3):370–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2007.04.004

Smith JA, Todd PE (2005) Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of nonexperimental estimators? J Econom 125(1–2):305–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.04.011

van den Berg GJ, Vikström J (2019) Long-run effects of dynamically assigned treatments: a new methodology and an evaluation of training effects on earnings. IZA discussion papers 12470, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA)

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of a larger project that received the financial support from the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation "EaSI" (2014-2020) and the Slovenian Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. The project was titled “Development of Social Policy Reform Strategies in Slovenia”, contract number FEP 2611-16-031400. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the institutions providing administrative, individual-level data, above all, to the Statistical Office of Slovenia, Employment Service of Slovenia, and Pension and Disability Insurance Institute of Slovenia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burger, A., Kluve, J., Vodopivec, M. et al. A comprehensive impact evaluation of active labour market programmes in Slovenia. Empir Econ 62, 3015–3039 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02111-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02111-6