Abstract

Knightian uncertainty represents a situation in which it is no longer possible to form expectations about future events. We propose a method to directly measure Knightian uncertainty. Our approach relies on firm-level data and measures the share of firms that do not formalize expectations about their future demand. We construct the Knightian Uncertainty Indicator for Switzerland and show that the indicator is able to identify times of high uncertainty. We evaluate the indicator by comparing it to established uncertainty measures. We find that a one standard deviation innovation of the Knightian Uncertainty Indicator leads to a negative and persistent reduction of investment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To be fair, Zarnowitz and Lambros (1987) already discuss the limitations to use dispersion as a proxy for uncertainty. However, the authors nevertheless believe in the ability of disagreement to approximate uncertainty.

Chang and Feunou (2013) provide a detailed discussion on the difference between implied and realized volatility.

See Shiller (1981) for a discussion on “excess volatility”.

Within the European Union (EU) and in the applicant countries the Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs provides a user guide on how to conduct regular harmonized surveys for different sectors (European Commission 2017).

The way we measure Knightian uncertainty might potentially underestimate the true Knightian uncertainty. De Bruin et al. (2000) show that individuals tend towards the middle category, when facing events with lower perceived control. One possible explanation of this observed phenomenon is that individuals seek to increase perceived control over their environment. Unfortunately, De Bruin et al. (2000) do not elucidate on the effects of item non-response.

Firms’ responses in KOF Business Tendency Surveys come mostly from CEOs and CFOs Abberger et al. (2014a).

For a discussion of unit non-response in Business Tendency Surveys, see Bannert and Dibiasi (2014).

These two question can be found in the KOF Construction Survey. Although between surveys questions on expected and realized demand may change slightly with respect to their wording, they are the same with respect to their content. All questionnaires are publicly available under https://www.kof.ethz.ch/en/surveys/business-tendency-surveys.html.

While in the paper we provide a thorough description of the construction of the indicator, we are unable to provide a complete picture of all practical choices. We invite everyone to look at our R-Script for the exact technical implementation of the indicator. All scripts will be provided on our website.

In Online-Appendix B.1, we investigate the sensitivity of this approach. Particularly, we bring all indicators to the lowest frequency, i.e. we transform all monthly data to quarterly series, and compute a quarterly Knightian Uncertainty Indicator. Our analysis shows that both indicators display the same trajectory of Knightian uncertainty.

We use chow-lin-maxlog implementation by the R package developed and maintained by Sax and Steiner (2013).

In the Online-Appendix B.2, we present an alternative aggregation method considering only actual available sectors.

The aggregate Knightian Uncertainty Indicator does change substantially if we transform quarterly to monthly series by keeping the quarterly values constant for each month and retrapolate using the long-term mean of each series.

Results to not significantly change if keep the weights constant for five years. For example, the value added figure for 2000 is kept constant until 2004; the value added figure from 2005 is kept constant until 2009. Results do also not change if we keep the values of 2015 constant for all years. However, attributing an equal weight to every indicator changes the indicator substantially.

We compute the aggregated Knightian Uncertainty Indicator since 1989 because before 1989 the indicator would reflect essentially the Knightian indicator of the manufacturing sector. See Table 1.

We include an extensive discussion of the calculation of each indicator in the Online-Appendix. Furthermore, all data will be provided on our website kof.ethz.ch/uncertainty.

Table 3 in the Online-Appendix provides an overview of the different macroeconomic and financial variables that are included in the survey.

The present indicator uses the standard deviation as a measure of dispersion. However, one can chose different dispersion measures. In the Online-Appendix, we compute the same indicator using the interquartile range.

Mokinski et al. (2015) provide a recent overview of common approaches to measure disagreement in qualitative survey data.

We prefer expected demand to expected production for two reasons. First, expected production is a function of expected demand and hence the relevant variable to consider. Second, the question on demand is not only asked to manufacturing firms, but similarly to firms of other industries.

We include a detailed description of the indicator in Online-Appendix (see A.4.1).

The original Economic Policy Uncertainty Index for different countries is published monthly on policyuncertainty.com. The index is available for Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Netherlands, Russia, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, UK and the USA. Furthermore, policyuncertainty.com publishes aggregate indicators for Europe and the world.

Online-Appendix A.1 provides a detailed discussion of the index. Besides an explanation of the technical implementation, we also present the keywords that we use to identify an article reporting on economic policy uncertainty.

The results are robust with respect to the chosen time horizon. In a robustness check that we provide in Table 5 in the Online-Appendix, we neglect VSMI and conduct the PCA using the remaining indicators since January 1991. The qualitative conclusion of the results remains unchanged.

Due to data limitations, the estimation using the economic policy uncertainty indicator is limited to 1991Q1 to 2018Q1.

In this analysis, we do not include the VSMI and the dispersion of professional forecasts as these indicators are available only since 1999 and 2001 respectively. We consider these time span as too short to produce meaningful results in a quarterly VAR.

Our findings do not change when detrending our variables according to Hamilton (2018). See Online-Appendix B.4 for more details.

References

Abberger K, Bannert M, Dibiasi A (2014a) Metaumfrage im dienstleistungssektor. KOF Analysen 8(2):51–62

Abberger K, Dibiasi A, Siegenthaler M, Sturm J-E (2014b) The swiss mass immigration initiative: the impact of increased policy uncertainty on expected firm behaviour. KOF Stud (53)

Alexopoulos M, Cohen J (2009) Uncertain times, uncertain measures. Working Paper, 352

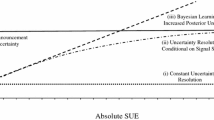

Bachmann R, Carstensen K, Lautenbacher S, Schneider M (2020) Uncertainty is more than risk–survey evidence on knightian and bayesian firms

Bachmann R, Elstner S, Sims ER (2013) Uncertainty and economic activity: evidence from business survey data. Am Econ J Macroecon 5(2):217–249

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2012) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. In: Labor markets and the business cycle in the aftermath of the great recession, federal reserve bank of minneapolis. Available at https://199.169.201.73/research/conferences/research-events---conferences-and-programs/~/media/files/research/events/2012_11-16/3-BakerBloomDavis.pdf. Accessed 13 Sep 2017

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2015) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2016) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ 131(4):1593–1636

Bannert M, Dibiasi A (2014) Unveiling participant level determinants of unit non-response in business tendency surveys. KOF Working Papers, 363

Baumgaertner S, Engler J-O (2016) Measuring knightian uncertainty. In: European association of environmental and resource economists 22nd annual conference, conference paper

Binding G, Dibiasi A (2017) Exchange rate uncertainty and firm investment plans evidence from swiss survey data. J Macroecon 51:1–27

Bloom N (2009) The impact of uncertainty shocks. Econometrica 77(3):623–685

Bloom N (2014) Fluctuations in uncertainty. J Econ Persp 28(2):153–175

Bloom N (2017) Observations on uncertainty. Aust Econ Rev 50(1):79–84

Bloom N, Bond S, Van Reenen J (2007) Uncertainty and investment dynamics. Rev Econ Stud 74(2):391–415

Boero G, Smith J, Wallis KF (2008) Uncertainty and disagreement in economic prediction: the bank of england survey of external forecasters*. Econ J 118(530):1107–1127

Bomberger WA (1996) Disagreement as a measure of uncertainty. J Money Credit Bank:381–392

Bond S, Moessner R, Mumtaz H, Syed M (2005) Microeconometric evidence on uncertainty and investment

Cascaldi-Garcia D, Datta DD, Ferreira TRT, Grishchenko OV, Jahan-Parvar MR, Londono JM, Loria F, Ma S, Rodriguez M, Rogers JH et al (2020) What is certain about uncertainty? Technical report, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Castelnuovo E (2019) Domestic and Global Uncertainty: A Survey and Some New Results. CESifo Working Paper Series (7900)

Chadefaux T (2014) Early warning signals for war in the news. J Peace Res 51(1):5–18

Chang BY, Feunou B (2013) Measuring uncertainty in monetary policy using implied volatility and realized volatility. Technical report, Bank of Canada Working Paper

Chow GC, Lin A-L (1971) Best linear unbiased interpolation, distribution, and extrapolation of time series by related series. Rev Econ Stat:372–375

Claveria O (2020) Uncertainty indicators based on expectations of business and consumer surveys. Empirica:1–23

Claveria O, Monte E, Torra S (2019) Economic uncertainty: a geometric indicator of discrepancy among experts‘ expectations. Soc Indic Res 143(1):95–114

Cramer J, Theil H (1954) On the utilisation of a new source of economic information: an econometric analysis of the munich business test: the 16th European Meeting OF the Econometric Society Uppsala, Sweden, 1954. Econometric Society Uppsala

De Bruin WB, Fischhoff B, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL (2000) Verbal and numerical expressions of probability: it‘s a fifty-fifty chance. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 81(1):115–131

Dibiasi A, Sarferaz S (2020) Measuring macroeconomic uncertainty: a cross-country analysis. KOF Working Paper Series (479):1–44

Engelberg J, Manski CF, Williams J (2009) Comparing the point predictions and subjective probability distributions of professional forecasters. J Bus Econ Stat 27(1):30–41

European Commission E (2013) European business cycle indicators. Technical report, Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs (ECFIN), Brussels. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/cycle_indicators/2013/pdf/3_en.pdf. Accessed 9 Sep 2017

European Commission E (2017) The Joint Harmonised EU Programme of Business and Consumer Surveys. European Economy-Reports and Studies

Ferderer JP (1993) Does uncertainty affect investment spending? J Post Keynesian Econ 16(1):19–35

Giordani P, Söderlind P (2003) Inflation forecast uncertainty. Eur Econ Rev 47(6):1037–1059

Guiso L, Parigi G (1999) Investment and demand uncertainty. Q J Econ:185–227

Hamilton JD (2018) Why you should never use the hodrick-prescott filter. Rev Econ Stat 100(5):831–843

Hisano R, Sornette D, Mizuno T, Ohnishi T, Watanabe T (2013) High quality topic extraction from business news explains abnormal financial market volatility. PloS one 8(6):e64846

Iselin D, Siliverstovs B (2013) The r-word index for switzerland. Appl Econ Lett 20(11):1032–1035

Jurado K, Ludvigson SC, Ng S (2015) Measuring uncertainty. Am Eco Rev 105(3):1177–1216

Keynes JM (1921) Treatise on probability

Keynes JM (1936) The general theory of employment, interest and money

Knight FH (1921) Risk, uncertainty and profit. Hart, Schaffner and Marx, New York

Leahy JV, Whited TM (1996) The effect of uncertainty on investment: Some stylized facts. J Money Credit Bank:64–83

Levi MD, Makin JH (1980) Inflation uncertainty and the phillips curve: some empirical evidence. Am Econ Rev:1022–1027

Makin JH et al (1982) Anticipated money, inflation uncertainty and real economic activity. Rev Econ Stat 64(1):126–34

Mokinski F, Sheng XS, Yang J (2015) Measuring disagreement in qualitative expectations. J Forecast 34(5):405–426

Mullineaux DJ (1980) Unemployment, industrial production, and inflation uncertainty in the united states. Rev Econ Stat:163–169

Neufeld AD (2015) Knightian Uncertainty in Mathematical Finance. PhD thesis, ETH Zurich

OECD (2003) Business Tendency Surveys: A Handbook. Number v. 291 in Business Tendency Surveys: A Handbook. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Rich R, Tracy J (2010) The relationships among expected inflation, disagreement, and uncertainty: evidence from matched point and density forecasts. Rev Econ Stat 92(1):200–207

Sax C, Steiner P (2013) Temporal disaggregation of time series. R J:5

Shiller RJ (1981) Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in dividends? Am Econ Rev 71(3):421–436

Theil H (1955) Recent experiences with the munich business test: an expository article. Econom J Econ Soc:184–192

Wei WWS (1994) Time series analysis: univariate and multivariate methods. Redwood City, Calif.: Addison-Wesley Pub., repr. with corrections edition

Zarnowitz V, Lambros LA (1987) Consensus and uncertainty in economic prediction. J Polit Econ:591–621

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article was the second chapter of my Ph.D. thesis (A. Dibiasi). I would like to thank my advisors Jan-Egbert Sturm and Klaus Abberger for the valuable comments and support. We further like to thank the participants of the SSES Annual Congress in Lausanne (June 2017) for their comments and useful suggestions on previous versions of this paper. We also thank our anonymous referees for excellent remarks and helpful suggestions. Financial support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) is gratefully acknowledged. All remaining errors are our own.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dibiasi, A., Iselin, D. Measuring Knightian uncertainty. Empir Econ 61, 2113–2141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02106-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02106-3