Abstract

We revisit the distributional implications of macroeconomic activity in the USA by estimating the effects of the unemployment and inflation rates on the quintile Lorenz ordinates. We have access to 16 years of additional data (1995–2010) that were not available for the earlier studies, covering the deepest recession since the Great Depression. These additional data do not substantively change the results regarding the effects of unemployment and inflation on income inequality (both increase it). Adding controls for other important macroeconomic variables that have increased substantially in recent decades (public transfers, government budget deficits, and openness to trade) also has little effect on the findings regarding unemployment and inflation. Changes in budget deficits are uniformly equalizing, and public transfers increase the share of the bottom 20% across different specifications. Greater openness to international trade increases inequality in some specifications but has little effect when we also include controls for public transfers and budget deficits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Dimelis and Livada (1999) also analyze the time series for the USA, along with three EU countries, but their methodology is very different from the other studies.

The link between income inequality and welfare theory was established by Atkinson (1970) and involves the cumulated income shares (Lorenz ordinates), not the income shares separately.

The Current Population Reports provide for the USA as a whole the Lorenz curves for family incomes, at the following points, bottom 20%, bottom 40%, bottom 60%, bottom 80%, and bottom 95%. Appendix A provides detailed data definitions.

Student maximum modulus (SMM) tables can be obtained from Stoline and Ury (1979). For deciles the 5% critical value is 2.80, and for quintiles, 2.50.

References

Achdut L (1996) Income inequality, income composition and macroeconomic trends: Israel, 1979–93. Economica 63:S1–S27

Anderson G (1996) Nonparametric tests of stochastic dominance in income distributions. Econometrica 64:1183–1193

Angello L, Sousa RM (2014) How does fiscal consolidation impact on income inequality? Rev Income Wealth 60:702–726

Atkinson A (1970) On the measurement of inequality. J Econ Theory 2:244–263

Atkinson AB, Piketty T, Saez E (2011) Top incomes in the long run of history. J Econ Lit 49:3–71

Barrett GF, Donald SG (2003) Consistent tests for stochastic dominance. Econometrica 71:71–104

Beach CM, Davidson R (1983) Distribution-free statistical inference with Lorenz curves and income shares. Rev Econ Stud 50:723–735

Bishop JA, Formby JP, Thistle PD (1989) Statistical inference, income distributions, and social welfare. In: Slottje DJ (ed) Research on economic inequality, vol 1. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 49–82

Bishop JA, Formby JP, Thistle PD (1992) Convergence of the south and non-south income distributions, 1969–1979. Am Econ Rev 82:262–272

Bishop JA, Formby JP, Sakano R (1994) Evaluating changes in the distribution of income in the United States. J Income Distrib 4:79–105

Björklund A (1991) Unemployment and income distribution: time-series evidence from Sweden. Scand J Econ 93:457–465

Blank RM, Blinder AS (1985) Macroeconomics, income distribution, and poverty. NBER Working Paper No. 1567

Blejer MI, Guerrero I (1990) The impact of macroeconomic policies on income distribution: an empirical study of the Philippines. Rev Econ Stat 72:414–423

Blinder AS, Esaki HY (1978) Macroeconomic activity and income distribution in the postwar United States. Rev Econ Stat 60:604–609

Buse A (1982) The cyclical behaviour of the size distribution of income in Canada: 1947–78. Can J Econ 15:189–204

Damjanovic T (2005) Lorenz dominance for transformed income distributions. Math Soc Sci 50:234–237

Davidson R, Duclos J-Y (2000) Statistical inference for stochastic dominance and for the measurement of poverty and inequality. Econometrica 68:1435–1464

Dickey DA, Fuller WA (1979) Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J Am Stat Assoc 74:427–431

Dimelis S, Livada A (1999) Inequality and business cycles in the U.S. and European Union countries. Int Adv Econ Res 5:321–338

Dutt P, Mitra D, Ranjan P (2009) International trade and unemployment: theory and cross-national evidence. J Int Econ 78:32–44

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 39:251–276

Felbermayr G, Prat J, Schmerer H-J (2011) Trade and unemployment: What do the data say? Eur Econ Rev 55:741–758

Granger CWJ (1969) Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37:424–438

Gustafsson B, Johansson M (1999) In search of smoking guns: What makes income inequality vary over time in different countries? Am Soc Rev 64:585–605

Hayes KJ, Slottje DJ, Porter-Hudak S, Scully G (1990) Is the size distribution of income a random walk? J Econom 43:213–226

Jäntti M (1994) A more efficient estimate of the effects of macroeconomic activity on the distribution of income. Rev Econ Stat 76:372–378

Johansen S (1988) Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J Econ Dyn Control 12:231–254

Johansen S (2014) Time series: cointegration, CREATES (Center for Research in the Econometric Analysis of Time Series) Research Paper 2014-38

Khattak D, Muhammad A, Iqbal K (2014) Determining the relationship between income inequality, economic growth & inflation. J Soc Econ Res Acad Soc Sci 1:104–114

Kwiatkowski D, Phillips PCB, Schmidt P, Shin Y (1992) Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. J Econom 54:159–178

Mocan HN (1999) Structural unemployment, cyclical unemployment, and income inequality. Rev Econ Stat 81:122–134

Nolan B (1989) Macroeconomic conditions and the size distribution of income: evidence from the United Kingdom. J Post Keynes Econ 11:196–221

Rajan RG (2010) Fault lines: how hidden fractures still threaten the world economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Stoline MR, Ury HK (1979) Tables of the studentized maximum modulus distribution and an application to multiple comparisons among means. Technometrics 21:87–93

Tse YK, Zhang X (2004) A Monte Carlo investigation of some tests for stochastic dominance. J Stat Comput Simul 74:361–378

Weil G (1984) Cyclical and secular influences on the size distribution of personal income in the UK: some econometric tests. Appl Econ 16:749–756

Wolff EN, Zacharias A (2007) The distributional consequences of government spending and taxation in the U.S., 1989 and 2000. Rev Inc Wealth 53:692–715

Woo J, Bova E, Kinda T, Zhang YS (2013) Distributional consequences of fiscal consolidation and the role of fiscal policy: What do the data say? International Monetary Fund (IMF) working paper WP/13/195

Xu K (1997) Asymptotically distribution-free statistical test for the generalized Lorenz curve. J Income Distrib 7:45–62

Xu K, Osberg L (1998) A distribution-free test for deprivation dominance. Econom Rev 17:415–429

Zheng B (2018) Almost Lorenz dominance. Soc Choice Welf 51:51–63

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Philip Rothman, Robert Kunst, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: Definition and measurement of variables

1.1 Dependent variable

Lx: Lorenz ordinate, where Lx is the cumulative share of family income. Incomes are ranked from lowest to highest and the ordinates are measured in percentage terms. We consider five Lorenz ordinates L1 = .2, L2 = .4, L3 = .6, L4 = .8, L5 = .95, where L5 is the combined share of family income of the bottom 95% of families. (Source: computed from the Current Population Reports, Series P-60)

1.2 Explanatory variables

Unemployment

Unemployment rate of all workers, measured in percentage terms. [Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)]

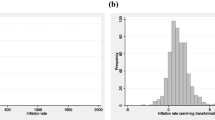

Inflation

Inflation rate computed as a first difference of the Consumer Price Index for urban areas. (Source: FRED)

Budget deficit

Ratio of government deficit, including both federal and local governments, to nominal GDP, measured in percentage terms. (Source: FRED)

Public transfers

Ratio of government (federal and local) transfer payments (to persons) to nominal GDP, measured in percentage terms. (Source: FRED)

Openness

Ratio of the country’s total trade (the sum of exports plus imports) to GDP. (Source: FRED)

Appendix B: Stage 1 cointegration estimates

See Table 7.

Appendix C: inference tests for Lorenz dominance

To test for Lorenz dominance, we follow Bishop et al. (1989, 1992), who propose a multiple comparison procedure. The multiple comparison procedure employs a union-intersection test. This procedure uses a fixed set of K quantiles (in our case quintiles) and their corresponding test statistics, T. In addition to the overall null hypothesis (H0) of pro-poor equality, there are two possible alternatives: pro-poor dominance (HA1) and crossing (HA2).

The overall null hypothesis is the logical intersection of the K sub-hypotheses, and the alternative hypotheses are the logical union of the K sub-hypotheses. To control for the probability of rejecting the overall null, we use the student maximum modulus, MK.Footnote 4 These test statistics for each of the sub-hypotheses are:

where the variance of L1 is given by Beach and Davidson (1983), or:

Therefore, we

-

1.

Reject H0 if |TGLi| > MK for i = 1, … K

-

2.

Accept HA1 if |TGLi| > MK for some i and |TGLi| <= MK for all other i,

-

3.

Accept HA2 if TGLi > MK for some i and − TGLi > MK for some other i.

Under (1), if each of the sub-hypotheses is not rejected, then the joint null hypothesis is not rejected, and we conclude that the explanatory variable is neither pro-equality nor anti-equality. On the other hand, if any of the sub-hypotheses are rejected, then the following are the possible outcomes:

-

Under (2): Weak Equality Dominance: If for some quantiles GLI > GL1 and for others GLI = GL1, then we conclude that the effect of the explanatory variable is weakly pro-equality. If GLI > GL1 for all i, then we have strong pro-equality.

-

Under (3): If for some quantiles GLI > GL1 and for others GLI < GL1, then no unambiguous ranking is possible for all z (a ‘crossing’ has occurred).

A number of alternative tests for stochastic dominance have been suggested (e.g., Anderson 1996; Xu 1997; Xu and Osberg 1998; Davidson and Duclos 2000; Barrett and Donald 2003, among others). Barrett and Donald (2003) note that Davidson and Duclos (2000) propose two types of test, the first being a Wald test. To implement this test, Barrett and Donald (2003, 83) note that “one must compute the solutions to a large number of quadratic programming problems in order to estimate the weights that appear in the Chi squared mixture limiting distribution.” Davidson and Duclos (2000, 1455) recognize the complexity of this test. The second test proposed by Davidson and Duclos has the Bishop, Formby, and Thistle (BFT) test structure. When Tse and Zhang (2004) provide size and power estimates of the Davidson and Duclos test, which they call “the DD test,” it has the BFT test structure with the variance–covariance structure from Davidson and Duclos (2000, 364). Tse and Zhang (2004) provide a review of these tests and extensive simulation results. We note that given the complex alternative hypothesis, no single test can completely rank Lorenz curves.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bishop, J.A., Liu, H., Zeager, L.A. et al. Revisiting macroeconomic activity and income distribution in the USA. Empir Econ 59, 1107–1125 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01729-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-019-01729-x