Abstract

This paper introduces a novel data set to examine the relationship between leverage and asset growth in the Canadian investment broker-dealer sector over the period of 1992–2010. Investment dealers have highly procyclical leverage, in that leverage growth is highly correlated with asset growth. This is largely due to collateralized borrowing, whereby increases in asset values lead to increases in collateral (margin deposits), allowing investment dealers to borrow against these deposits and purchase more assets. Of course, decreases in collateral value have the opposite effect and margins can be destabilizing if investment broker-dealers are forced to de-leverage.

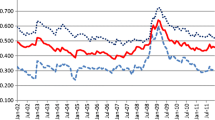

Source: IIROC 1992–2010. Converted from monthly to annual (last observation)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Margins are the difference between a securities price and its collateral value.

This fact is captured in different ways by Adrian and Boyarchenko (2015), Adrian and Shin (2014), Aymanns and Farmer (2015), and Ma (2018), for example, who all study the impact of Value-at-Risk constraints on the risk premium for assets correlated with leverage. Danielsson et al. (2004) is an early paper that documents price dynamics and the impact of Value-at-Risk constraints on generating procyclicality.

Similar arguments are made in the macroeconomics literature linking credit constraints over the business cycle. See for example Kiyotaki and Moore (1997).

TD Bank founded Toronto Dominion Securities Inc. in 1987. TD Bank would later buy Waterhouse Securities in 1996 for $715 million. BMO purchased a majority share of Nesbitt Burns; RBC purchased a majority share of Dominion Securities; BNS purchased McLeod Young Weir; CIBC purchased a majority share of Wood Gundy; and National purchased Levésque Beaubien.

The Canadian Investor Protection Fund provides insurance of up to $1 million against investment dealer insolvency for clients. The blank report schedules are publicly available http://tinyurl.com/llst4v4.

These practices, available on IIROC’s Web site, govern issues like front running and client priority.

For confidentiality reasons, we do not have access to firm names but instead firm identifiers which remain constant through time. In addition, we note that there are 325 firms in total—119 is the minimum and 201 maximum for any one period. This points to substantial entry and exit over our sample period, and therefore, we use an unbalanced panel.

We exclude from our analysis throughout this paper firms that appeared for less than one year in our data as well as firms that in 2010 were members of Group A. Group A is firms known as introducing brokers. They can advise clients but must perform transactions through a broker in one of the other Groups B–F.

The Big 6 banks in Canada are Bank of Montreal, Banque Nationale, Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Royal Bank, Scotiabank, TD-Canada Trust.

Deferred income taxes and capitalized leases were included in capital prior to 1993. Subsequently, non-current capitalized leases were split into a category for long-term liabilities and financial statement capital.

Standby subordinated debt is a form of contingent capital. It reflects the commitment from the lender to advance a certain amount on demand. Therefore, cash is only transferred when needed. To avoid circumvention, IIROC added a margin charge for deposits with a provider of capital.

In the period before the elimination of standby subordinated debt, several firms had standby facilities that when added with their regular capital exceeded their asset holdings. This causes their leverage to be less than one.

IIROC uses an early warning system to monitor potentially vulnerable members. Any member with risk-adjusted capital less than 5% of total margin is a category 1 warning and a member with risk-adjusted capital less than 2% of total margin is a category 2. Sanctions for violations are outlined in IIROCs instructions to members.

The assumptions for a random coefficients model are strongly rejected using a Hausman test.

There is not much evidence that fair-value accounting contributes to procyclicality. See for example Laux and Leuz (2010).

See Morris and Shin (2008) for an example of how changes in margins are sufficient to produce procyclical leverage.

References

Adrian T, Boyarchenko N (2015) Intermediary leverage cycles and financial stability. Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff report No. 567

Adrian T, Shin H (2010) Liquidity and leverage. J Financ Intermed 19:418–437

Adrian T, Shin H (2014) Procyclical leverage and value-at-risk. Rev Financ Stud 27:373–403

Aymanns C, Farmer J (2015) The dynamics of the leverage cycle. J Econ Dyn Control 50:155–179

Baglioni AE, Beccalli AB, Monticini A (2013) Is the leverage of european banks pro-cyclical? Empir Econ 45:1251–1266

Beccalli E, Boitani A, Giuliantonio SD (2015) Leverage pro-cyclicality and securitization in US banking. J Financ Intermed 24:200–230

Brunnermeier M, Pedersen L (2009) Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Rev Financ Stud 22:2201–2238

Chowdhry B, Nanda V (1998) Leverage and market stability: the role of margin rules and price limits. J Bus 71:179–210

Damar E, Meh C, Terijima Y (2013) Leverage, balance sheet size and wholesale funding. J Financ Intermed 22:639–662

Danielsson J, Shin H, Zigrand J (2004) The impact of risk regulation on price dynamics. J Bank Finance 28:1069–1087

Freedman C (1996) Financial structure in Canada: the movement towards universal banking. In: Saunders A, Walter I (eds) Universal banking: financial system design reconsidered, vol 20.1. Irwin Professional Publishing, New York

Geanakoplos J (2009) The leverage cycle. In: Acemoglu D, Rogoff K, Woodford M (eds) NBER macroeconomics annual, vol 24. University of Chicago Free Press, Chicago, pp 1–65

Gornall W, Strebulaev I (2013) Financing as a supply chain: the capital structure of banks and borrowers. NBER working paper 19633

Griliches Z, Regev H (1995) Firm productivity in Israeli industry 1979–1988. J Econom 65:175–203

Kalemli-Ozcan S, Sorensen B, Yesiltas S (2012) Leverage across firms, banks, and countries. J Int Econ 88:284–298

Kiyotaki N, Moore J (1997) Credit cycles. J Political Econ 105:211–248

Laux C, Leuz C (2010) Did fair-value accounting contribute to the financial crisis? J Econ Perspect 24:93–118

Laux C, Rauter T (2017) Procyclicality of U.S. bank leverage. J Account Res 55:237–273

Ma S (2018) Heterogeneous intermediaries and asset prices. Working paper

Morris S, Shin H (2008) Financial regulation in a system context. Brooking papers on economic activity, pp 229–261

Rosengren E (2014) Broker-dealer finance and financial stability. In: Keynote remarks: conference on the risks of wholesale funding sponsor

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank IIROC, especially Nellie Gomes and Louis Piergeti for providing data and support. Additional thanks to Toni Ahnert, Evren Damar, Toni Gravelle, Sheisha Kulkarni, David Martinez-Miera, Teodora Paligorova and Ilya Strebulaev for their useful comments and advice as well as seminar participants at the University of Waterloo. Vathy Kamulete and Chloé Yao provided excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors. No responsibility for them should be attributed to the Bank of Canada.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, J., Usher, A. Investment dealer collateral and leverage procyclicality. Empir Econ 58, 489–505 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1553-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1553-1