Abstract

Papers attempting to explain female labour force participation either do not include women-specific variables or lack a proper dynamic specification. In this paper, we estimate a dynamic equation for female labour force participation in OECD countries from 1980 to 2007, taking into account several sets of variables. Moreover, we use our model to predict the results for 2007–2011, and we find that our model adjusts quite well to the actual data even with regard to the out-sample observations during the ongoing recession. In order to gain further insight concerning the interpretation and robustness of the equation, it is then compared to a similar equation for males. Our results show that real wage is one of the most relevant variables for female participation. Thus our specification could also be useful to endogenise labour force participation for a macro-labour market framework such as that of Layard et al. (1991, rev. 2005). However, women’s preferences, the overall level of education, and other structural factors are also important.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The objectives of the EU are to become a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy. Thus, one of the targets is to reach a 75 % employment rate for women and men aged 20–64 by 2020. In countries such as Ireland and Spain, this rate did not reach 60 % for women in 2010 and in Italy it did not reach 50 %. In the past, similar benchmarks had already been set by the so-called Lisbon Strategy, using a rather dubious effect. See Destefanis and Mastromatteo (2012) for a recent analysis.

The function \(F\) is homogeneous of degree zero all its arguments.

Following Clark and Summers (1982), the wage dynamics and the path dependence of the participation arise directly from the utility function, since both past and future experience are included in the utility function.

Some authors such as Pissarides (1991) have included the gender wage gap, instead of real wages, for the labour force equation.

The unemployment rate is also expected to capture the cyclical labour market pressures better than other business cycles.

From that point of view, home production is crucial to explain women’s weaker attachment to the labour market as home production is often regarded as a better alternative to market production for women than for men.

Childcare subsidies reduce the relative price of formal childcare and, therefore, increase the relative return of market work. Nevertheless, their effectiveness could be reduced if women substitute formal for informal childcare

Nevertheless, as she also said, part-time work could entail a wage penalty, low social security coverage, job insecurity, and little training, i.e. it could risk marginalising women in these jobs.

The tax system imposes excessive distortions on the labour supply decisions of married women relative to those of men and single women. Optimal taxation implies that the total deadweight loss of the tax system is reduced if marginal tax rates are lower for those individuals whose labour supply is more elastic to tax rates (Boskin and Sheshinski 1983). The relevant marginal tax rate for a married women is effectively taxed more heavily than for men and single women, providing scope for a move to neutrality.

Although the peer effects are more important in the long run, they might play a significant role in the short run reinforcing or diminishing the added worker effect under a negative shock.

See Sevestre and Trognon (1985) for the magnitude of this asymptotic bias in dynamic error component models.

Countries included are Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the USA.

Applying the Fisher’s test for the panel unit root using an augmented Dickey-Fuller test (two lags), we were not able to reject the possibility that prime-age female labour force participation, overall female labour force participation, prime-age male labour force participation, and overall male labour force participation contain a unit root at a level of 1 %. Note that labour force participation is bounded between 0 and 1, so a unit root would in principle make no sense. Nevertheless, in the 1980–2007 period, labour force participation has risen considerably and may have been out of its steady-state path.

Note that the assumption \(E\left( \mu _{i}\triangle y_{i2}\right) =0\) does not imply that the country-specific effects play no role in employment determination. The assumption means that there is no correlation between employment and the country-specific effect in the absence of conditioning on other variables.

Windmeijer (2005) proposes a finite-sample correction for the asymptotic variance of the two-step GMM estimator.

In order to test the endogeneity of the variables, we used the difference-Sargan test for subgroups of variables. Real wage and the share of part-time jobs appear to be endogenous for female labour force participation (both prime-age women and women of working age), while none of the variables turn to be endogenous in the male equation.

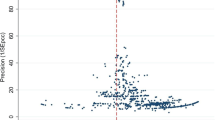

It is well known that OLS levels will give an estimate of \(\delta \) that is biased upwards in the presence of individual-specific effects (see Hsiao 1986, for example), and that within groups will give an estimate of \(\delta \) that is seriously biased downwards in short panels (see Nickell 1981). Thus a consistent estimate of \(\delta \) can be expected to lie in between the OLS levels and Within Groups estimates.

The static equation is estimating by using xtivreg2 (Schaffer 2010).

Within the Arellano and Bond (1991) procedure, AR(1) residuals are not detrimental to estimation, while AR(2) residuals are. None of our dynamic specifications show autocorrelation of second order and Sargan tests performed well in all of them.

See Arellano and Bond (1991) for more details about long-run calculations. Standard errors are calculated using Delta method.

We calculated the relative unemployment rate as the male unemployment rate/female unemployment rate.

We attempted to include other variables such as share of married women or share of parliament seats occupied by women but none of these variables appeared to be significant. Moreover, the sample diminished substantially.

This variable is difficult to measure, and there is no commonly agreed definition. Genre et al. (2010) used the length of leave allowed for each woman; Jaumotte (2003) considered the maximum leave in any sector and OECD calculated the leave taking into account whether mothers received 100 % of their wages or not. Results differed according to the definition of leave.

Additional ‘family-friendly institutions’ would include childcare benefits or public childcare spending, although none of these appear to be significant. This could be attributable to lack of data, since it is difficult to find valid data and the series are too short. We do not list these estimations because the variables in question considerably reduce the sample.

They performed several estimations for prime-age female participation. In contrast, we use the equation that focuses on the labour institutions, since this is the cited authors main contribution.

The unemployment benefit could have a positive effect since more generous unemployment benefit systems represent a positive incentive to participate in the labour market.

In this eclectic equation, we did not include maternity leave and unemployment benefit since they do not appear to be significant in the encompassing equation.

The share of workers employed in the services sector shows the same effect on female labour force participation as the share of women with part-time jobs. These two variables are highly correlated and insignificant when included together in the estimation.

For example, the first subsample for the block of 10 consecutive years would be from 1980 to 1990, the second from 1981 to 1991, and so on until the last sub-sample from 1997 to 2007. Five consecutive years estimations start in 1982, since most of the countries has missing values in the first two years (1980 and 1981).

For the period after 2008, the OECD does not provide data for the incidence of part-time jobs based on the national definition (the definition that we have been using in our database in order to obtain data from 1980). For this reason, we extrapolate the value of part-time jobs based on the national definition for 2008–2010 using the trend of the incidence of part-time jobs based on the common definition.

In order to check the efficiency of our forecast Granger and Huang (1997), we applied the white noise Portmanteau (Q) test and Bartlett’s periodogram-based test. Neither test was able to reject the null hypothesis that the errors follow a white noise, and consequently our prediction does not show persistent errors.

Recall however the exception from the Nordic countries (already highlighted in Genre et al. 2010).

References

Anderson TW, Hsiao C (1982) Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. J Econom 18(1):47–82

Andolfatto D (1996) Business cycles and labor-market search. Am Econ Rev 86(1):112–132

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68(1):29–51. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

Ashenfelter O (1972) Racial discrimination and trade unionism. J Polit Econ 80(3):435–464

Barro RJ, Lee J-W (2001) International data on educational attainment: updates and implications. Oxf Econ Pap 53(3):541–563

Bassanini A, Duval R (2006) The determinants of unemployment across oecd countries: reassessing the role of policies and institutions. OECD Econ Stud 42(1):7

Bassanini A, Duval R (2009) Unemployment, institutions, and reform complementarities: re-assessing the aggregate evidence for oecd countries. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 25(1):40–59. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grp004

Becker Gary S (1957) The economics of discrimination. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois

Bertola G, Blau FD, Kahn LM (2007) Labor market institutions and demographic employment patterns. J Popul Econ 20(4):833–867

Blanchard O, Wolfers J (2000) The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of european unemployment: the aggregate evidence. Econ J 110(462):1–33

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Blundell R, Bond S, Windmeijer F (2001) Estimation in dynamic panel data models: improving on the performance of the standard GMM estimator. In: Baltagi BH, Fomby TB, Hill RC (eds) Advances in Econometrics: Nonstationary panels, panel cointegration, and dynamic panels, vol 15. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, U. K, pp 53–91

Bond S, Hoeffler A, Temple J (2001) Gmm estimation of empirical growth models. Economics Papers 2001-W21, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Boskin MJ, Sheshinski E (1983) Optimal tax treatment of the family: married couples. J Public Econ 20(3):281–297. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(83)90027-0

Cain GG (1966) Married women in the labor force. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois

Cain GG, Dooley MD (1976) Estimation of a model of labor supply, fertility, and wages of married women. J Polit Econ 84(4):S179–S199

Cain GG, Mincer J (1969) Urban poverty and labor force participation: comment. Am Econ Rev 59(1):185–194

Clark KB, Summers LH (1982) Labour force participation: timing and persistence. Rev Econ Stud 49(5):825–844

Destefanis S, Mastromatteo G (2012) Assessing the reassessment: a panel analysis of the lisbon strategy. Econ Lett 115(2):148–151. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2011.12.035

Eckstein Z, Lifshitz O (2011) Dynamic female labor supply. Econometrica 79(6):1675–1726

Eckstein Z, Wolpin KI (1989) Dynamic labour force participation of married women and endogenous work experience. Rev Econ Stud 56(3):375–390

Francesconi M (2002) A joint dynamic model of fertility and work of married women. J Labor Econ 20(2):336–380

Friedman M (1962) Price theory: a provisional text. Aldine, Chicago

Gauthier AH, Bortnik A (2001) Comparative maternity, parental, and childcare database, version 2. University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

Genre V, Gómez-Salvador R, Lamo A (2005) 5. The determinants of labour force participation in the European Union1. In: Labour supply and incentives to work in Europe, p 195

Genre V, Gómez Salvador R, Lamo A (2010) European women: Why do (n’t) they work? 1. Appl Econ 42(12):1499–1514

Granger WC, Huang LL (1997) Evaluation of panel data models: some suggestions from time series. Discussion paper 97–10, University of California, San Diego

Greene WH (2002) Econometric analysis. Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Hayakawa K (2007) Small sample bias properties of the system gmm estimator in dynamic panel data models. Econ Lett 95(1):32–38

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econom J Econom Soc 47(1):153–161

Hotz VJ, Miller RA (1988) An empirical analysis of life cycle fertility and female labor supply. Econom J Econom Soc 56(1):91–118

Hsiao C (1986) Analysis of panel data. Econometric Society Monograph no. 11. New York, NY

Jaumotte F (2003) Labour force participation of women: empirical evidence on the role of policy and other determinants in oecd countries. OECD Econ Stud 2(9):51–108

Judson RA, Owen AL (1999) Estimating dynamic panel data models: a guide for macroeconomists. Econ Lett 65(1):9–15

Layard R, Nickell S, Jackman R (1991) Unemployment. macroeconomic performance and the labour market, rev. 2005

Lucas RE Jr, Rapping LA (1969) Real wages, employment, and inflation. J Polit Econ 77(5):721–754

Martin JP (1996) Measures of replacement rates for the purpose of international comparisons: a note. OECD Econ Stud 26(1):99–115

Mincer J (1962) Labor force participation of married women. In: Universities-National Bureau (eds) Aspects of labor economics, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, pp 63–106

Moffitt R (1984) Profiles of fertility, labour supply and wages of married women: a complete life-cycle model. Rev Econ Stud 51(2):263–278

Möller J, Aldashev A (2006) Interregional differences in labor market participation. Jahrb für Regionalwiss 26(1):25–50

Mortensen DT, Pissarides CA (1994) Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Rev Econ Stud 61(3):397–415

Nickell S (1981) Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econom J Econom Soc 49(6):1417–1426

Nickell W (2006) The CEP-OECD institutions data set (1960–2004). Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science

Nickell S, Layard R (1999) Labor market institutions and economic performance. Handb Labor Econ 3:3029–3084

Nickell S, Nunziata L (2001) Labour market institutions database. Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, London

OECD (2011) Product market regulation database.https://www.oecd.org/economy/pmr

Pissarides CA (1991) Real wages and unemployment in Australia. Economica 58(229):35–55

Pissarides C, Garibaldi P, Olivetti C, Petrongolo B, Wasmer E (2005) Women in the labor force: How well is Europe doing?. In: Boeri T, Del Boca D, Pissarides CA, Women at Work: an Economic Perspective, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 7–115

Roodman D (2009a) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system gmm in stata. Stata J 9(1):86–136

Roodman D (2009b) A note on the theme of too many instruments*. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 71(1):135–158

Ruhm CJ, Teague JL (1997) Parental leave policies in Europe and North America. Gender and family issues in the workplace

Schaffer M (2010) Xtivreg2: stata module to perform extended iv/2sls, gmm and ac/hac, liml and k-class regression for panel data models. Statistical software components, Boston College, Department of Economics. http://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s456501

Schultz TP (1990) Testing the neoclassical model of family labor supply and fertility. J Human Resour 25(4):599–634

Sevestre P, Trognon A (1985) A note on autoregressive error components models. J Econom 28(2):231–245

Soto M (2006) System gmm estimation with a small number of individuals. Institute for Economic Analysis, Barcelona

Tanda P (2001) Politiche sociali: Selettività e universalismo. ISAE Report

Vendrik M (1998) Unstable bandwagon and habit effects on labor supply. J Econ Behav Organ 36(2):235–255

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step gmm estimators. J Econom 126(1):25–51

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author wishes to acknowledge the financial support of Xunta de Galicia, through the fellowship programme Ánxeles Alvariño and Univerversity of Vigo (bolsas de mobilidade). I also acknowledge comments on a previous version of this paper from Sergio Destefanis (University of Salerno), participants at VII Jornadas de Economa Laboral, IDEGA seminars (University of Santiago), Applied Economics seminars (University of Vigo) and AME cluster seminars (University of York). Also, comments from two anonymous referees and the associated editor are acknowledged.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Database

-

Childcare benefits: This measures the increase in household disposable income from child benefits (including tax allowances). We obtained the data from Bassanini and Duval (2006).

-

Consumer price index: This measures the average changes in the prices of consumer goods and services purchased by households. In most instances, the Consumer price index is compiled in accordance with international statistical guidelines and recommendations. However, national practices may depart from these guidelines, and these departures may have an impact on international comparability between countries. We use data from OECD (on line: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

-

Gross benefit replacement rates: Average across the first five years of unemployment for two earnings levels, three family situations and three durations of unemployment. Data are obtained from the OECD (on line: www.oecd.org/els/social/workincentives).

-

Labour force participation rate: This represents active people as a percentage total population of the same age and sex. The economically active population (labour force) comprises employed and unemployed people. It is obtained from the OECD labour base (on line: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

-

Part-time share: This represents people employed on a part-time basis as a percentage of the same age population. The full-time/part-time distinction with regard to the main job is made on the basis of a spontaneous answer given by the respondents in all countries, except for the Netherlands, Iceland, and Norway where part time and full time are determined on the basis of whether the usual number of hours worked are, respectively, fewer or more than 35, and for Sweden, where this criterion is applied to the self-employed as well. The data were taken from OECD. The definition of part-time work varies considerably across OECD countries, but three main approaches can be distinguished: i) a classification based on the worker’s perception of his/her employment situation; ii) a cut-off (generally 30 or 35 hours per week) based on the usual number of working hours, with people who usually work fewer hours being considered part-timers; iii) a comparable cut-off based on actual hours worked during the reference week. We used data from OECD (on line: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

-

Product market regulation: This indicator summarises regulatory provisions in seven non-manufacturing sectors: telecoms, electricity, gas, postal service, rail transport, air passenger transport, and road freight. This indicator covers sectors in which anti-competitive regulation tends to be concentrated, given that manufacturing sectors are typically lightly regulated and open to international competition in OECD countries. The range is 0,6 increasing in regulation. Data are obtained from OECD (2011), Product Market Regulation Database (www.oecd.org/economy/pmr).

-

Public expenditures on childcare: This measures public spending on formal day care and pre-primary school per child, in 1995 PPP-US$. Data on formal day care do not include tax expenditures (i.e. tax allowances and tax credits for childcare expenses) unless they are refundable. Spending on pre-primary school includes both direct and indirect, i.e. transfers and payments to private entities expenditures. We used data from Bassanini and Duval (2006).

-

Relative marginal tax rate on second earners: This is defined as the ratio of the marginal tax rate on the second earner to the tax wedge for a single-earner couple with two children earning 100 % of APW earnings. It represents the share of additional income that goes into paying increased household taxes when a previously inactive spouse takes up a job. We used data from Bassanini and Duval (2006).

-

Tax wedge: This is defined as the ex-post wedge computed from national accounts as the sum of the employment tax rate, the direct tax rate, and the indirect tax rate. The main source is the CEPOECD Institutions Data Set (1960–2004) from Nickell (2006). But the data from Ireland show missing values and were replaced with data from Nickell and Nunziata (2001) in order to obtain a larger set of observations (the series were fairly homogeneous).

-

Total fertility rate: This is defined as the average number of live births a woman would have by age 50 if she were subject, throughout her life, to the age-specific fertility rates observed in a given year. Its calculation assumes that there is no mortality. The total fertility rate is expressed as the number of children per woman. The data are taken from OECD (online: http://www.oecd.org/document0,3746,en_2649_201185_46462759_1_1_1_1,00.html).

-

Total labour cost: Compensation of employees (COE) compiled according to the System of National Accounts 1993, adjusted for the self-employed by multiplying COE by the ratio of total hours worked by all people in employment to total hours worked by all employees of businesses. Concepts exclude the cost of employee training, welfare amenities and recruitment; taxes on employment (e.g. payroll tax) and fringe benefits tax. Time series were extended back to 1970 for most OECD Member countries linking the series with related historical time series made available to the OECD sometime in the past. Total labour costs for economic activities refer to G-K (Market Services) and C-K (Business Sector). We use data from OECD (on line: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

-

Total unemployment rate: This represents unemployed persons as a percentage of same age and sex active population as a percentage of total population. Unemployed people are defined as people who were without work during the reference week and were currently available for work and were either actively seeking work in the past four weeks or had already found a job to start within the next three months. The date were obtained from OECD (on line: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

-

Union density: Trade union density corresponds to the ratio of wage and salary earners who are trade union members, divided by the total number of wage and salary earners. We use data from OECD (on line:http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx).

Appendix 2: Behaviour of the coefficients when we reduce the number of instruments. OLS and FE estimations as a control

See Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pena-Boquete, Y. Further developments in the dynamics of female labour force participation. Empir Econ 50, 463–501 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0931-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0931-1