Abstract

Migration from rural areas to urban population centers has long been associated with modernization; a pattern one might expect to accelerate as advancing climate change degrades rural land-based livelihoods. Does rural–urban migration of arctic Indigenous peoples follow a similar pattern? Has depopulation of rural arctic areas accelerated as climate-driven environmental change has intensified in the rapidly warming arctic? What are the main drivers of mobility, both historically and more recently? We address these questions through a review and synthesis of empirical studies of rural–urban migration of arctic Indigenous peoples using individual records over the past four decades, along with analysis of new data informed by those previous studies. The use of microdata allows us to incorporate variation in individual situations and choices as well as community characteristics that vary across space and time, permitting us to make inferences about factors associated with decisions to move. The evidence shows that rural–urban migration patterns appear largely to have persisted over the decades, but some drivers have changed. Living costs appear to have replaced livelihood opportunities as the dominant driver since 2000. Other changes in decisions to move are complex, and require additional research to understand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Migration has played an important role in shaping demographic change across the Circumpolar Arctic (Heleniak 2015). Migration from rural areas to growing urban centers associated with modernization has typically involved livelihood transformation, specifically a change from land-based livelihoods to industry and service-based livelihoods. To a large extent, one would expect arctic Indigenous peoples to follow a similar pattern. However, several important differences separate arctic peoples from rural residents of other developing regions. First, the rural Arctic is remote from the nearest urban area and other regions of the nation. Second, although experiencing colonization like many other recently modernizing areas, arctic colonization is internal rather than external, with the colonized region incorporated into the colonizing nation-states, whichis unlike the similarly remote Amazon region, are advanced industrial nations. Finally, rural arctic hunting and herding livelihoods represent more than just a way of making a living; they form an intrinsic part of an entire social, economic, and cultural system based on household production that deeply attached to identity (Stammler 2009; Wolfe and Walker 1987).

Arctic Indigenous peoples’ experiences with modernization, including the historical similarities and differences with other modernizing areas, raise questions about rural–urban migration. What are historical patterns of mobility, including geographic flows, gender differences, and regional differences, and how can they be explained? Has depopulation of rural arctic areas accelerated as climate-driven environmental change has intensified in the rapidly warming arctic? What are the main drivers of mobility, and have drivers and patterns of rural–urban migration changed over the years as modernization has progressed?

We address these questions through a review and synthesis of empirical studies that used microdata to analyze internal migration of arctic Indigenous peoples over the past four decades. These studies, mainly addressing mobility of Alaska Native peoples, but also including some data from arctic Canada and other arctic states, applied discrete choice models to administrative microdata to analyze individual mobility decisions. Themes that emerged from the review informed the design of a new study that examines changing migration patterns of Alaska Indigenous peoples in the twenty-first century. The objective is to understand which individuals are more or less likely to move from specific community or regional origins to specific community or regional destinations, based on characteristics of origin and destination places as well as characteristics of individuals. Use of microdata permits us to take advantage of spatial and temporal variation in individual situations and choices to infer factors associated with decisions to move. In general, the data show that although patterns appear largely to have persisted, drivers have changed in ways that are complex, and require additional research to understand.

Before discussing rural–urban migration of arctic Indigenous peoples, we first define what we mean by rural and urban in the Alaska context. Then we briefly review the theoretical framework for analyzing mobility patterns for Arctic Indigenous peoples. Next, we discuss a series of empirical studies that apply the framework, beginning with the 1990 US Census, and the various patterns or themes that emerged from that research. We then describe the new research. Data sources included US Census Long Form survey data, other survey data, the Aboriginal Peoples Survey administered by Statistics Canada, and Alaska state microdata. Many of the studies involved analysis of protected confidential datasets accessed through the US Census Bureau and Statistics Canada Research Data Centers, or through arrangements with research analysts at the Alaska Department of Labor and Workplace Development (DoLWD). Then we present new research on mobility between 2000 and 2016 using protected Census data, discussing how findings relate to previous studies and describing limitations. The concluding section summarizes the study findings and offers suggestions for future research.

2 Background

2.1 The study region

We generally use the Arctic Council political geography to define arctic North America, which includes the state of Alaska, the Canadian territories, and Greenland. The few roads in this region mainly connect the urban areas—Anchorage and Fairbanks, Alaska, along with Whitehorse and Yellowknife, Canada—to more southerly regions. Outside these urban centers, the predominantly Indigenous population lives in scattered small communities, few of which are road-connected, where they were settled by colonial governments at various points in the twentieth century. For studying population mobility, we define rural Alaska as Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) 400, labeled the Subsistence Alaska PUMA by the US Census Bureau in the 2010 Census (Fig. 1). The boundaries of PUMA 400 shifted slightly but not materially from 2000 to 2010. In the 1990 Census, the PUMA 300 region encompassed the same area as PUMA 400 in 2000 (Ratcliffe et al. 2016).

(Source: US Census Bureau, 2021)

2010 Census Public Use Microdata Areas in Alaska: Rural Alaska defined as PUMA 400 (Subsistence Alaska PUMA)

Urban Alaska has generally been defined as Anchorage and its neighboring suburbs in the Matanuska-Susitna Borough, and other communities of more than 10,000 people (Fairbanks, Juneau and Ketchikan) (Fischer and Wolfe 2003). The remainder of the state, which is largely road-connected and majority non-Indigenous but relatively lightly populated, receives relatively few Indigenous migrants and is largely ignored in these mobility studies. Supplementary Appendix A provides additional detail describing Alaska historical political geography informing the definition of urban and rural regions.

We generally consider the entirety of Arctic Canada and Greenland outside the territorial capitals to be rural. Because of a multitude of economic and structural differences from North America, this review excludes the Eurasian Arctic, except for a brief discussion of the Chukotka region of Russia, a similarly mainly undeveloped area not connected by road to an urban center with a high-percentage of Indigenous population.

2.2 General mobility patterns

Indigenous Alaskans, defined as self-identified American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people by the US Census Bureau, are relatively mobile and have been so for decades. Much of this migration proceeds from rural to urban Alaska, but also in the reverse direction. Huskey et al (2004) estimated a net movement of 4% of adult AIAN men and 6% of women from rural to urban regions of Alaska between 1985 and 1990. The slow rural net out-migration was insufficient, however, to offset natural increase, resulting in slow growth of the rural AIAN population of 3–4% per decade (US Census Bureau, decennial census data). AIAN people also move frequently between nearby communities within PUMA 400 (Huskey et al. 2004; Howe et al. 2014). Cross-border movement of Indigenous peoples within the Circumpolar Arctic, while common until borders began to be enforced in the mid-twentieth century, is now relatively rare.

Indigenous migration rates in other North American arctic regions are lower than Alaska, most likely due to greater distances between communities and resulting higher costs of travel compared to Alaska. This has resulted in somewhat faster population growth in rural arctic Canada (Berman and Howe 2012).

2.3 General theoretical framework: migration as an indicator of relative utility

Many studies of internal migration estimate statistical models to test hypotheses about determinants without an explicit underlying theory of what would motivate people to leave, and where they would go if they moved. Most of these studies examine mobility patterns using aggregate data for geographic areas, obscuring potentially differing patterns for different subpopulations. Analyzing individual decisions has a much greater potential to understand determinants of mobility for a minority population such as Arctic Indigenous peoples if it is done within a consistent theoretical framework. For this study, we apply a model for analyzing Arctic migration consistent with long-established migration models for place-based amenities (Tiebout 1956; Knapp and Graves 1989) that broadly considers migration as an indicator of relative utility from living in a place.

Studies of migration among arctic Indigenous peoples often associate migration with opportunities to generate earnings (Alonso and Rust 1976; Huskey et al. 2004). For arctic Indigenous peoples, the subsistence economy is known to be relevant to utility, but rarely considered in migration studies. One of the main reasons for this omission is that subsistence participation and harvest data are not systematically measured across places (Kruse 2011). A number of place-based amenities may also be important in addition to subsistence opportunities.

Figure 2, from Berman (2009), outlines a more complete model of migration as a choice between two places to live, based on the well-being (utility) potentially attainable from living in each place. A person living in place A attains a certain utility from living there, based on individual and household characteristics, as well as characteristics of the place. The person who has knowledge of conditions in place B may attain a projected utility from living in place B, based on household characteristics and characteristics of place B. For a move from A to B to be worth undertaking, the projected utility in place B has to exceed the utility experienced in place A by more than the cost of moving from A to B. A simple extension of this model would consider options to live in multiple places, with a choice to move to whichever place in the portfolio would generate the highest utility, net of moving costs.

(Source: Berman 2009)

Theoretical Framework: Migration as an Indicator of Relative Well-Being at the Community Level

3 Review and analysis of previous studies

3.1 Studies with census microdata

The review of empirical studies applying the general theoretical framework to model mobility decisions of arctic Indigenous peoples begins with the 1990 US Census. Huskey et al. (2004) examined mobility information in PUMS microdata from the Census Long Form Survey, which contains information on the PUMA where the respondent resided in 1985 as well as residence in 1990. Howe et al. (2014), Berman and Howe (2012, 2014), and Howe and Huskey (2022) analyzed moves from 1995 to 2000 in microdata from the 2000 Census Long Form Survey. Berman and Howe (2012, 2014) and Berman (2013b, a) also modeled analogous migration decisions of Canada Inuit from 1996 to 2001 in 2001 Canada Census data. These studies utilized protected confidential records accessed in Research Data Centers operated by the US Census Bureau and Statistics Canada.

3.2 Studies using Alaska state microdata

Several other studies analyzed mobility of rural Alaska residents using State of Alaska microdata. Research analysts at the Alaska DoLWD with access to confidential state records were able to link individual employment security records with applications for the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) by social security number. Nearly all Alaska residents file applications for the PFD each year. DoLWD employment records contain quarterly information on employment and earnings by employer, occupation, and place of work, while PFD applications contain age, gender, and place of residence. Linking the two sets of records enables one to create a panel of annual observations on individuals, regardless of whether or not they work in Alaska for any or all years since the PFD records were systematically recorded electronically in the early 2000s. PFD records do not include information on race or ethnicity. However, it is generally possible to identify and exclude most non-Indigenous rural Alaska residents by screening out occupations and industries associated with jobs with few Indigenous workers, such as teachers, and workers in construction trades, oil and gas, and mining. Studies analyzing mobility using state records include Berman (2017) and Berman et al. (2020).

3.3 Survey of living conditions in the arctic

Official government statistics do not collect systematic data on non-market harvesting of local foods and other traditional home production activities, making it difficult to test hypotheses about the importance of traditional activities in mobility decisions. The Survey of Living Conditions in the Arctic (SLiCA) was conducted as an add-on to the 2001 Aboriginal Peoples Survey in Inuit areas of Canada by Statistics Canada. SLiCA was fielded privately in 2003 in three Alaska regions (North Slope Borough, Northwest Arctic Borough, and Nome Census Area), as well as in Greenland, and Chukotka (Kruse et al. 2008); it included detailed questions on traditional activities of arctic Indigenous peoples. The survey did not provide data on actual mobility choices, except for Canada, where it could be linked to Census returns. However, it did include a question on migration intent, specifically, “How likely are you to move away from your community in the next five years?” Berman (2009) examined migration intent in Alaska SLiCA survey returns, and Berman (2021) compared Alaska responses to those of Indigenous residents of Arctic Canada, Greenland, and Chukotka. Howe et al. (2014) and Berman and Howe (2012, 2014) applied subsistence participation equations estimated by Berman (2009) from SLiCA data to project individual, household, and place characteristics associated with participation and success in traditional activities in Census mobility data in Alaska and Inuit regions of Canada.

3.4 Emerging themes

A number of themes emerged from the aforementioned studies of migration choices. We briefly review these themes, which serve as hypotheses to test in the subsequent analytical work described in the next section.

3.4.1 Employment opportunities

Huskey et al. (2004) noted the importance of employment opportunities as a driving force for migration to urban centers. They noted that individuals most likely to succeed in the cash economy—generally younger, more educated workers—were likely to move to urban areas. While earnings opportunities attracted migrants, higher wages—earnings per hour—discouraged migration.Footnote 1 A likely explanation is that participation in the subsistence economy required some cash, but also time off from working for pay. A concern arose more recently that attempts to create full-time well-paying shift-work jobs in remote rural regions might cause more rural Indigenous people who take those jobs to move to urban areas, where there were more opportunities enjoy a high-income lifestyle. Berman et al. (2020) investigated that concern, finding that mobility was higher for rural residents hired to work at the Red Dog mine in Northwest Alaska, but only slightly so. The study uncovered a more important limitation of such enterprises’ ability to improve rural village living standards: Most Indigenous workers hired by the mine were already living in urban areas when they were initially hired, despite concerted efforts to recruit in rural communities in the region.

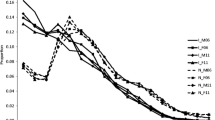

3.4.2 Gender, age, and education

Huskey et al. (2004) and Howe et al. (2014) noted that women were slightly more likely than men to move from rural to urban areas. Although the differences were relatively small on an annual basis (see Fig. 2), they accumulated over time. This follows a pattern observed in several other studies (Hamilton et al. 2016; Hamilton and Seyfrit 1994; Martin 2009). Hamilton and Seyfrit (1994) noted that differential out-migration rates from small Alaska communities were associated with gender differences in educational attainment, which suggests a potential interaction of gender with educational attainment. Young women were on average more motivated to complete high school and potentially higher education in order to leave rural areas, with young men generally more interested in maintaining traditional harvesting activities. Such a gendered pattern in livelihood aspirations has also been observed elsewhere in the Arctic (Hansen et al. 2012).

3.4.3 Subsistence opportunities

Many arctic Indigenous residents living in remote rural areas continue to practice traditional subsistence livelihoods that involve hunting, fishing, and gathering and ancillary activities in a system of household production (Wolfe and Walker 1987; Poppel B 2014). Subsistence opportunities have been noted as an important to life satisfaction of arctic Indigenous residents (Condon et al. 1995). If opportunities to engage in traditional livelihood pursuits keep people in place, then migration patterns should reflect this. While individual characteristics such as educational attainment are salient for success in the modern economy, traditional economy relies on household production, making it important to consider household characteristics as well. Berman (2009, 2021) found evidence that individual and place characteristics associated with success in subsistence economies were important determinants of migration intent in Alaska, and to a lesser extent in Canada. However, this was not the case in Greenland or Chukotka, where subsistence appeared to function more as the rural employer of last resort rather than a positive choice for people unable to leave struggling rural communities. Howe et al. (2014) and Berman (2012, 2014) did not find a strong association of subsistence opportunities with migration decisions in Alaska Census microdata, but did find such evidence in arctic Canada.

3.4.4 Stepping stones pattern

A prominent feature of the economic geography of rural Alaska is the role of regional hub communities—population 2,000–7,000—that serve as administrative and economic centers serving smaller communities in the surrounding hinterlands (Goldsmith 2007). Regional centers, with their associated spoke and hub air transportation networks, become intermediary stopping points between urban centers and small rural communities. Howe et al. (2014) found that these hub communities also played an important role in a “stepping stones” pattern of migration (Fig. 3). Migrants from rural villages were much more likely to move to regional hubs than directly to urban areas, and moves to villages were mostly from their regional hub community. In turn, most migrants to cities came from regional centers, and movers from cities went predominantly to one of the regional hubs. Regional hub communities are also found in Canada and Greenland, but the pattern is somewhat more complicated than in Alaska. Berman and Howe (2012, 2014) found a stepping stones migration pattern in Arctic Canada by showing that the number of flight segments required to travel between any two communities strongly predicted the likelihood of moving there.

Stepping stones model of hierarchical internal migration adapted from Howe et al (2014)

3.4.5 Living costs

Although the high cost of living in rural arctic areas is often informally discussed as a factor encouraging people to leave, there is very little systematic data on living cost differences. Food costs are measured in many Alaska hub communities (https://uaf.edu/ces/files/fcs/2009q3data.pdf), but not in villages. However, fuel cost data are available for most places. The high cost of fuel is an inescapable issue for rural arctic communities. Fuel for space heating in tundra areas with no local firewood consumes a large fraction of household budgets (Szymoniak et al 2008). Fuel for getting around on the land is essential for engaging in traditional activities. Most electricity is still generated by diesel power, and the lack of road access means that most products are brought in by air. Berman (2017) examined the hypothesis that high and rising fuel prices were contributing to rural Alaska out-migration, finding that while there was an effect, its magnitude was relatively small. Nevertheless, it is certainly a potential contributing factor.

3.4.6 Other factors

Several other place-related factors have been found in the various studies, but many of these are not reliability measured. One potential exception is the lack of infrastructure, especially availability of good-quality housing. Housing quality varies greatly among rural communities and has been found to be associated with mobility in several studies (Howe and Huskey 2022; Berman 2012, 2021).

The SLiCA survey found that primary reasons for temporary moves included education and health care, as well as opportunities to earn income (Poppel et al. 2007). Most moves from rural Alaska for post-secondary education and training opportunities would be offset by return flows when training is completed. A net outflow requires a permanent move, which would be for a different reason than for education. The healthcare system in rural Alaska is structured along the transportation hierarchy shown in Fig. 3, with hospitals located in the regional hubs, and specialist clinics in Anchorage, so would reinforce the stepping stones pattern of movement.

Place characteristics may interact with household characteristics. For example, having children in the household could increase moving costs, but might also promote from moving to more urban places with better educational opportunities. Children may also affect subsistence participation, if families seek to pass on cultural traditions tied to identity to the next generation. That would promote return migration. Place characteristics are also relevant to moving costs, as some places may be more accessible than others.

4 New research

These themes that emerged in previous research were incorporated as hypotheses to consider in a new study that examined the stability and change in rural Alaska migration patterns since 2000.

4.1 Data sources

Data on migration outcomes and individual and household characteristics came from the US Census Bureau records. We assembled all individual and household records in the 2000 Census Long Form Survey for individuals age 16 and older identifying as AIAN, alone or in combination with other race or races who either lived in Alaska in 2020 or lived in some other state and identified an Alaska community as their residence in 1995. To that data set, we added the analogous American Community Survey (ACS) records from 2005, the first year the ACS was conducted in Alaska, through 2016. After reconciling multiple differences in variable definitions and codes between the Census Long Form Survey and the ACS and among the different ACS years and excluding children under 16, the combined data set contained about 68,000 records.

To this data set, we added in several other sets of place characteristics from public sources. These characteristics included heating fuel prices from a biennial fuel cost survey (Alaska Division of Community and Regional Affairs, no date), and ecological characteristics reflecting historical availability of important subsistence food species potentially affected by climate change. Three non-exclusive attributes represented availability of caribou, salmon, and marine mammals (coastal areas) (Alaska Division of Subsistence, no date). Finally, all data were adjusted to reflect constant 2015 dollars using the Anchorage Consumer Price Index. Because the research involved confidential individual Census and ACS records, all research was conducted within the Census Research Data Center (RDC) environment.

4.2 Empirical model

Following the basic model outlined in Fig. 2, the empirical model of migration decisions for arctic indigenous people starts with the idea that utility in a place or region depends on local livelihood opportunities, other characteristics of the place, and personal attributes. That is,

where UAi represents utility of person i attainable in place A, YAi represents livelihood opportunities available to person i in place A, XA represents a vector of place characteristics, and Zi represents a vector of characteristics of person i and his or her household. The term eAi represents additional components of utility that are unobserved by the analyst, although revealed to the individual making the decision.

If individual i resides at place A, she or he may contemplate how UAi might compare to utility available in another place B: UBi. In order for the individual to be willing to move to place B, the gain in utility must exceed the moving cost MABi; i.e.,

The individual’s potential livelihood opportunities available in different destinations are expectations and depend on individual, household, and place characteristics, i.e., YBi = Y(XB, Zi). If there are J potential destinations rather than just the two, the individual who starts at place A would be presumed to choose the residence location that maximizes.

where MAAi = 0.

If we assume that the εAi are independently and randomly distributed with a type one extreme value distribution, and the utility function (1) follows certain properties, then a multinomial logit model of migration choice estimates the indirect utility of residing in each place consistent with the random utility model (McFadden 1981).

4.3 Estimation methods

We estimated multinomial logit equations for Eq. (4) using regional geography to reflect 20 Alaska origin–destination regions, with outside Alaska (other US states and territories) representing an additional region (Table 1). Rural regions included the six regional hubs (Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) Kotzebue, Nome, Bethel, Dillingham, and Kodiak) separated from surrounding rural villages in the same rural region, to model the intermediate stepping stones. The number of flight segments represented stepping stones nodes in the spoke and hub air transportation network in Rural Alaska, which lack a connected road or rail network. The regional hubs contain substantially more job opportunities than smaller villages, but fewer subsistence opportunities.

Potential earnings opportunities in the various destination options, YBi = Y(XB, Zi), vary according to place as well as individual attributes, and must be projected for each individual i to each potential destination place. We estimated censored regressions for the natural logarithm of earnings separately for men and women for each of three large labor market regions: Urban Alaska (PUMA 100a, 100b, 200, 300, or areas 1 through 5), Rural Alaska (PUMA 400, encompassing areas 6–20), and outside Alaska (area 21). Explanatory variables in the earnings equations included a large number of individual and household characteristics along with separate constant terms for each of the origin–destination regions within each labor market region. The unbiased predicted values from the estimated regressions for an individual with the same individual and household characteristics were used to project potential earnings in each of the destination regions.

We designed the choice equations to test for effects of employment opportunities, gender differences, and cost of living in the form of fuel costs. Because the 2000 Census question on mobility inquires about place of residence five years previously, while the ACS questions ask about residence one year ago, we expected far fewer people in the ACS data would have indicated that they had moved. To adjust for the difference in time horizon, we estimated a different intercept for the stay in place destination after 2000.

5 Results

Table 2 displays the results of estimating Eq. (4) combining both genders.Footnote 2 Older adults, especially older women, are more likely to stay in the current place of residence, as are people with children under 18. The number of flight segments and its square represent the stepping stones hypothesis. The coefficient on flight segments is large and significant in both directions; however, there is a preference, which is increasing, for moving toward more urban destinations up the stepping stones hierarchy. As expected, the coefficient representing the increased likelihood for the option to stay in the same community after 2000 is large and highly significant. That said, the magnitude is far lower than proportional to the reduced time horizon in the mobility question from the transition to the ACS. If out-migration is constant per year over a five-year period, the probability of leaving in one year should be one-fifth the probability of leaving over 5 years (odds ratio = 0.25), implying a coefficient on the increment to the stay option of 1.39 (log of 1/0.25). Instead, the coefficient is only 0.76, suggesting that about half the people who leave the community every year are temporary migrants, returning to their origin place within five years.

Earnings and living costs were both important in 2000. However, there is a significant negative trend for the earnings effect. Living costs, represented by local fuel prices, is also a significant factor. Equations estimated separately for men and women found surprisingly few significant differences, beyond the built-in gender difference in earnings opportunities in rural villages. Table 3 shows the signs and probabilities of the tests for differences in the coefficients across genders. The full equation results were suppressed by the Census Bureau to protect respondent privacy. Earnings opportunities represent the largest factor driving migration decisions up to 2000. After that, the effect declines, and even becomes negative and significant after 2010. Living costs and the increasing preference for moving up the stepping stones hierarchy away from small villages became dominant. Community characteristics behind the increasing preference for urban moves were either not significant or not observed in the data available for this study.

6 Discussion

The strong association of the mobility pattern with the hub and spoke air transportation network indicates that the stepping stones pattern found by Howe et al. (2014) persists into the twenty-first century, illustrating the persistence of the structure established to facilitate colonial administration of the Indigenous population decades before Alaska became a state. However, the increasing urban preference—directionally moving up more than down the hierarchy in Fig. 3—suggests that return migration is becoming less frequent than it was before 2000. Despite the historical net rural-to-urban migration in Alaska's predominantly Indigenous rural regions, much of the migrants out of rural villages still move only to the next step—the rural regional hub—affirming Howe’s (2009) finding that the majority of migration remains within the rural region.

Canada lacks the hub and spoke transportation system developed in Alaska, creating a much more vertical hierarchical migration pattern (Berman and Howe (2012, 2014). Greater isolation and lack of road connections in the rural Arctic limit the ability to compare arctic Indigenous mobility to migration patterns of Indigenous peoples outside the Arctic, although the circular migration pattern between rural homelands and urban areas is also a prominent theme among Indigenous peoples in Australia and New Zealand (Bell and Taylor 2004; Barcham 2004). Institutional and economic differences also complicate comparisons between the North American Arctic and Eurasia. The caution notably applies to Russia, where withdrawal of support for communities in the Russian North following the dissolution of the Soviet Union led to severe hardship, lower life-expectancy, and declining births, affecting population dynamics more than out-migration (Petrov 2008; Heleniak 2019).

Surprisingly, we did not find evidence of gender differences favoring female out-migration. The only significant association with gender was an interaction with age, specifically, a reduced likelihood of moving for older women. That said, higher female educational attainment translates into a substantially higher earnings potential in more urban locations, which would have favored female out-migrants. The fading of earnings as a driver of migration after 2000 raises the question of whether the “female flight”—also noted in Greenland (Rasmussen (2009) but not in Canada (Downsley and Southcott 2017)—may have faded in rural Alaska.

Although data on subsistence are not systematically available, earlier research noted that subsistence opportunities would appear to retain people in Alaska and to some extent in Canada. We did not find evidence that migration rates were associated with availability of regional subsistence resources that might be affected by climate change. This aligns with Hamilton et al. (2016) who found no link between population change and climate. Chi et al. (2024) reviewed studies for effects of climate-related environmental change more broadly, finding little evidence for an effect. We cannot rule out the possibility, however, that environmental change may underlie part of the unexplained recent rural-to-urban trend.

Although access to Census microdata provided a unique opportunity to investigate detailed origin–destination moves, the strict requirements that the Census Bureau placed on disclosure of results to protect privacy of respondents limit what could be presented. The change from the five-year time horizon in the Census Long Form Survey to the one-year horizon in the ACS may limit what we infer about changes after 2000, if temporary migrants go to different destinations for different motivations. However, the main findings of change post-2000—reduced importance of earnings and an increased preference for more urban destinations—are significant as trends rather than as a change in levels.

The mobility patterns analyzed in the current study examine an origin–destination matrix that is much more detailed than previous studies of Alaska Indigenous peoples. Even so, the impracticality of modeling each of over 140 communities separately, and the aggregation into the regional rural village origins excludes the possibility of analyzing a number of potential drivers that vary at the community level. These include housing and other infrastructure and alcohol control status, found by Howe and Huskey (2022) to be associated with specific community-to-community moves.

7 Conclusion/Synthesis

Over the past 30 years, the empirical evidence developed in this paper suggests that the main drivers of rural–urban migration of Alaska Indigenous peoples have changed from those uncovered in previous studies of arctic Indigenous migration using administrative microdata. Up to 2000, migration from rural to urban areas was driven by employment opportunities (earnings). Gender differentials in earnings in regional hub and urban areas relative to villages drove gender disparities in migration. Since 2000, living costs, especially fuel costs, have eclipsed earnings as the main driver. People appear to be moving away from earnings opportunities. However, it is important to emphasize that statistical association with potential drivers does not necessarily mean causation.

Other factors not measured that might create an enhanced preference for urban environments such as health care, opportunities for youth, and family reunification may also have increased in importance, and need further study. Although these new results apply only to Alaska, other arctic regions face the same fuel cost increases, and potentially similar social change associated with globalization that might point toward a preference for a more urban lifestyle. Future research is needed to determine if the changes found in Alaska apply elsewhere in the Arctic.

Notes

. Evaluating coefficients of probit equations at the sample mean, Huskey et al (2004) estimated suggest that a 10% increase in relative earnings increased the probability that a rural resident moved to an urban area by 26% (95% Conf. Int. 16–37%) for men, and 14% (95% Conf. Int. 4–24%) for women. Correspondingly, a 10% increase in the rural wage rate decreased the probability of moving by 8% (95% Conf. Int. 7–9%) for men.

. Because the equations had to be estimated within the US Census RDC, The Census Bureau imposed strict limits on the scope of statistical results that could be released to the public. The suppressed results included equations to project earnings in the different regions, which contained a large number of highly significant individual and household variables. The results in Table 2 represent the equation estimated with only significant variables included, to reduce the disclosure risk of displaying coefficients and standard errors for the insignificant individual and household characteristics.

References

Alaska division of subsistence (no date) community subsistence information system: CSIS, Alaska department of fish and game. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/sb/CSIS/index.cfm

Alonso W, Rust E (1976) The evolving pattern of village Alaska. Federal-state land use planning commission for Alaska study No. 17, Anchorage

Barcham M (2004) The politics of Maori mobility. In: Taylor J, Bell M (eds) Population mobility and indigenous peoples in Australasia and North America. Routledge, London, New York, pp 163–183

Berman M (2009) Moving or staying for the best part of life: theory and evidence for the role of subsistence in migration and well-being of Arctic Inupiat residents. Polar Geogr 32(1–2):3–16

Berman M (2013a) Remoteness and mobility: transportation routes, technologies, and sustainability in Arctic communities. Gumanit Issled Vnutr Azii (inn Asia Hum Stud) 2013(2):19–31

Berman M (2021) Household harvesting, state policy, and migration: evidence from the survey of living conditions in the Arctic. Sustainability 13:7071. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137071

Berman M, Howe EL (2013b) Remoteness, transportation infrastructure, and urban-rural population movements in the Arctic. In: Hansen KG, Rasmussen RO, Weber R (eds) Proceedings from the First International Conference on Urbanisation of the Arctic, 28–30 August 2012, Ilimmarfik, Nuuk, Greenland. Nordregio, Stockholm, pp 109–121

Berman M, Loeffler R, Schmidt J (2020) Long-Term Benefits to indigenous communities of extractive industry partnerships: evaluating the red dog mine. Resour Policy 16:101609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101609

Berman M, Howe EL (2012) Comparing migration decisions of inuit people in arctic canada and Alaska. Paper presented to the Western regional science association 2012 annual meeting, Poipu, HI, February 2012

Berman, M (2017) Energy costs and rural Alaska out-migration. Institute of social and economic research. https://iseralaska.org/publications/?id=1627

Chi G, Zhou S, Mucioki M, Miller J, Korkut E, Howe L, Yin J, Holen D, Randell H, Akyildiz A, Halvorsen KE (2024) Climate impacts on migration in the Arctic North America: existing evidence and research recommendations. Reg Environ Change 24(2):47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-024-02212-9

Condon R, Collings P, Wenzel G (1995) The best part of life: subsistence hunting, ethnicity, and economic adaptation among young adult Inuit males. Arctic 48(1):31–46

Alaska division of community and regional affairs (no date) Alaska fuel price report: current community conditions, biennial. https://www.commerce.alaska.gov/web/dcra/MappingAnalyticsandDataResources/fuelpricesurvey.aspx

Dowsley M, Southcott C (2017) An initial exploration of whether ‘female flight’ is a demographic problem in Eastern Canadian Arctic Inuit communities. Polar Geogr 40:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1272647

Fischer V, Wolfe R (2003) Methods for rural/non-rural determinations for federal subsistence management in Alaska final report. Anchorage: Institute of social and economic research. https://iseralaska.org/publications/?id=1047.

Goldsmith S (2007) The remote rural economy of Alaska. Institute of social and economic research. http://pubs.iseralaska.org/media/dd8decae-2ad7-4e07-a74e-abcb689c82ef/uak_remoteruraleconomyak.pdf.

Hamilton SC (1994) Coming out of the country: community size and gender balance among Alaskan natives. Arct Anthropol 31:16–25

Hamilton LC, Saito K, Loring PA, Lammers RB, Huntington HP (2016) Climigration? Population and climate change in Arctic Alaska. Popul Environ 38:115–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-016-0259-6

Hansen KG, Rasmussen RO, Olsen LS, Roto J, Fredricsson C (2012) Megatrends in the Arctic. Nordregio, Stockholm

Heleniak T (2019) Where did all the men go? The changing sex composition of the russian north in the post-soviet period, 1989–2010. Polar Rec (gr Brit) 56:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224741000615

Heleniak T (2015) Arctic populations and migration, Arctic human development report, copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers, pp 53–104

Howe EL (2009) Patterns of migration in Arctic Alaska. Polar Geogr 32:69–89

Howe EL, Huskey L (2022) Crossing frozen ground: tiebout, local public goods, place amenities, and rural-to-rural migration in the Arctic. J Rural Stud 89:130–139

Howe EL, Huskey TL, Berman M (2014) Migration in Arctic Alaska: empirical evidence of the stepping stones hypothesis. Migr Stud 2(1):97–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnt017

Huskey TL, Berman M, Hill A (2004) Leaving home, returning home: migration as a labor market choice for Alaska natives. Ann Reg Sci 38(1):75–92

Knapp TA, Graves PR (1989) On the role of amenities in models of migration and regional development. J Reg Sci 29(1):71–87

Kruse J (2011) Developing an Arctic subsistence observation system. Polar Geogr 34(1–2):9–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2011.584448

Kruse J, Poppel B, Abryutina L, Duhaime G, Martin S, Poppel M, Kruse M, Ward E, Cochran P, Hanna V (2008) Survey of living conditions in the Arctic (SLiCA). In: Møller V, Huschka D, Michalos AC (eds) Barometers of quality of life around the globe. Social indicators research series. Springer, Dordrecht, p 33

Martin S (2009) The effects of female out-migration on Alaska villages. Polar Geograph 32(1–2):61–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10889370903000455

Petrov AN (2008) Lost generations? Indigenous population of the Russian north in the post-Soviet era. Can Stud Popul 35:269. https://doi.org/10.25336/p6jw32

Poppel B, Kruse J, Duhaime G, Abryutina L (2007) SLiCA results. Anchorage, Institute of social and economic research

Poppel B (2014) Subsistence in the arctic. In: Michalos AC (ed) Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer, Netherlands, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2910)

Rasmussen RO (2009) Gender and generation: perspectives on ongoing social and environmental changes in the Arctic. Signs J Women Cult Soc 34:524–532. https://doi.org/10.1086/593342

Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, Fields A (2016) Defining rural at the United States Census Bureau. Am Commun Surv Geogr Brief 1(8):1–8

Stammler F (2009) Reindeer nomads meet the market culture, property and globalisation at the end of the land. Halle Studies in the Anthropology of Eurasia, LIT Verkag, Berlin, p 102

Szymoniak N, Haley S, Saylor B (2008) Webnote 1. Estimated household costs for home energy use. Institute of social and economic research. https://iseralaska.org/publications/?id=1202

Taylor J, Bell M (2004) Continuity and change in indigenous Australian population mobility. In: Taylor J, Bell M (eds) Population mobility and Indigenous peoples in Australasia and North America. Routledge, Londan and New York, pp 13–43

Tiebout C (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. J Polit Econ 64:416–424

US Census Bureau (2021) 2010 Census Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA) Reference Maps. https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-maps/2010/geo/2010-pumas.html.

Wolfe RJ, Walker RJ (1987) Subsistence economies in Alaska: productivity, geography, and development impacts. Arct Anthropol 24(2):56–81

Funding

The authors received financial support for this research from the National Science Foundation, awards #1216399 and #2032786, and logistical support provided by the US Census Center for Economic Studies, and the California Census Research Data Center at the University of Southern California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.