Abstract

This paper analyzes international migration streams to Belgian municipalities between 1994 and 2007. The Belgian population register constitutes a rich and unique database of yearly migrant inflows and stocks broken down by nationality, allowing us to empirically explain the location choice of newly arriving immigrants at the municipality level. Specifically, we aim at separating the network effect from other location-specific characteristics such as local labor or housing market conditions and the presence of public amenities. Our main contribution to the migration literature is to model labor and housing market variables as operating at different levels, assuming that immigrants first select a region roughly corresponding to a labor market and subsequently choose a municipality within this region that maximizes their utility. Among other things, this allows us to shed new light on the still ongoing discussion in the literature concerning the impact of labor market characteristics on the location of immigrants. We find that the spatial repartition of immigrants in Belgium is determined by both network effects and local characteristics. The relative importance of the determinants of location choice varies by nationality, as expected, but for all nationalities, local factors matter more than networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Illegal migrants and asylum seekers do not appear in these statistics. Most origin countries included in our empirical analysis are, however, unlikely to be sending out many asylum seekers and illegal migrants.

An average municipality is 52 squared kilometers large, hosts about 17,500 inhabitants or 695 inhabitants per squared kilometer. Furthermore, the available surface varies between 1 and 214 square kilometers; the population size ranges from 963 to 466 203; and population densities take values between 20 and 23,785 inhabitants per square kilometer.

Municipalities that never received an immigrant throughout the period of observation get disregarded, as the sample size would be too small to obtain consistent and therefore reliable parameter estimates for these countries.

Note that the immigrant stock is reported each year on January 1.

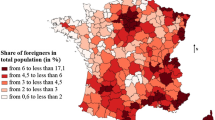

For more geographical details on the three Belgian regions, as well as the exact location of the main cities, see Figure B-1 in the Online Appendix.

Note that we consider new arrivals only, i.e., immigrants coming from abroad choosing a location within the country.

In the empirical section, locations are defined as 1 of the 588 Belgian municipalities, while areas correspond to 1 of the 43 government districts.

More details on this specification are available in the Online Appendix C.

As usual when an independent variable is discrete, only differences are identified. This is not a problem, as only these differences matter.

More details on this specification may be found in the Online Appendix D.

In order to avoid taking the log of zero, we add unity to the immigrant stock variables before calculating population shares.

The time fluctuations in the immigrant stock are to some extent related to naturalization allowed by modifications in the Belgian nationality law. Our variable is, however, robust to these fluctuations as long as immigrants’ naturalization behavior is homogenous across municipalities (See Online Appendix D).

One exception is Damm (2009) who investigates the influence of regional factors on the secondary location choices of Danish refugees who were randomly assigned to their initial location by the authorities between 1986 and 1998.

The same holds for variables capturing environmental conditions: There is not much climatological variation across locations which renders its inclusion uninformative.

The minimum distance to the national border is measured as the geodesic distance to the nearest national border from the centroid of each municipality, measured in thousands of kilometers.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrices are available in the Online Appendix Tables A-3 to A-5. Overall, pairwise correlations are fairly limited.

We tested the robustness of our results for regional policy differences affecting immigrants (mainly regarding integration courses that were compulsory in Flanders from 2003 onwards but optional in Brussels and Wallonia). Estimation results—available upon request—confirm our results. We are very thankful to a referee for pointing this out.

It might be argued that a large inflow of immigrants in a municipality could create pressure on the housing market, boosting housing prices and the number of transactions. Given that we consider bilateral immigrant flows, however, the effect of migration on housing prices and transactions is likely to be minor. In order to test for potential reverse causality, we re-estimated the model using the first, second or third lag of housing prices. Though not reported here for brevity, the results (available upon request) are robust to whether these variables are lagged or not.

References

Åslund O (2005) Now and forever? Initial and subsequent location choices of immigrants. Reg Sci Urban Econ 35(2):141–165

Accetturo A, Manaresi F, Mocetti S, Olivieri E (2014) Don’t stand so close to me: the urban impact of immigration. Reg Sci Urban Econ 45:45–56

Anselin L (1988) Spatial econometrics: methods and models, vol 4. Springer, Berlin

Arbaci S (2008) (Re)viewing ethnic residential segregation in Southern European cities: housing and urban regimes as mechanisms of marginalisation. Hous Stud 23(4):589–613

Bartel A (1989) Where do the new US immigrants live? J Labor Econ 7(4):371–391

Bauer T, Epstein G, Gang I (2002) Herd effects or migration networks? The location choice of Mexican immigrants in the US. IZA Discussion Paper 551

Bauer T, Epstein G, Gang I (2005) Enclaves, language, and the location choice of migrants. J Popul Econ 18(4):649–662

Beine M, Docquier F, Rapoport H (2008) Brain drain and human capital formation in developing countries: winners and losers. Econ J 118:631–652

Bertoli S, Fernández-Huertas Moraga J (2013) Multilateral resistance to migration. J Dev Econ 102:79–100

Bertoli S, Brücker H, Fernández-Huertas Moraga J (2013) The European crisis and migration to Germany: expectations and the diversion of migration flows. IZA Discussion Paper 7170

Blázquez M, Llano C, Moral J (2010) Commuting times: is there any penalty for immigrants? Urban Stud 47(8):1663–1686

Boeri T (2010) Immigration to the land of redistribution. Economica 77:613–800

Borjas G (1993) L’impact des immigrés sur les possibilités d’emploi des nationaux. Migrations Internationales, le Tournant, Paris, OCDE pp 215–222

Borjas G (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374

Buckley FH (1996) The political economy of immigration policies. Int Rev Law Econ 16(1):81–99

Carrington W, Detragiache E, Vishwanath T (1996) Migration with endogenous moving costs. Am Econ Rev 86(4):909–930

Chau N (1997) The pattern of migration with variable migration cost. J Reg Sci 37(1):35–54

Chiswick BR, Miller PW (2004) Where immigrants settle in the United States. IZA Discussion Paper 1231(1231)

Clark X, Hatton TJ, Williamson JG (2007) Where do U.S. immigrants come from, and why? Rev Econ Stat 89:359–373

Clemens M (2011) Economics and emigration: trillion dollar bills on the sidewalk. J Econ Perspect 25:83–106

Crozet M, Mayer T, Mucchielli JL (2004) How do firms agglomerate: a study of FDI in France. Reg Sci Urban Econ 34:27–54

Damm A (2009) Determinants of recent immigrants’ location choices: quasi-experimental evidence. J Popul Econ 22(1):145–174

Docquier F, Rapoport H (2012) Globalization, brain drain, and development. J Econ Lit 50:681–730

Docquier F, Peri G, Ruyssen I (2014) The cross-country determinants of potential and actual migration. Int Migr Rev 48(S1):37–99

Dodson ME (2001) Welfare generosity and location choices among new United States immigrants. Int Rev Law Econ 21(1):47–67

Drever AI, Clark WA (2002) Gaining access to housing in Germany: the foreign-minority experience. Urban Stud 39(13):2439–2453

Dustmann C, Frattini T, Preston I (2012) The effect of immigration along the distribution of wages. Rev Econ Stat 80:145–173

Edin PA, Fredriksson P, Åslund O (2003) Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants—evidence from a natural experiment. Q J Econ 118(1):329–357

Epstein G (2008) Herd and network effects in migration decision-making. J Ethn Mig Stud 34(4):567–583

Friedberg R, Hunt J (1995) The impact of immigrants on host country wages, employment and growth. J Econ Perspect 9(2):23–44

Gallardo-Sejas H, Gil-Pareja S, Llorca-Vivero R, Martínez-Serrano J (2006) Determinants of European immigration: a cross-country analysis. Appl Econ Lett 13(12):769–773

Heitmueller A (2003) Coordination failures in network migration. IZA Discussion Paper 770

Jayet H, Ukrayinchuk N (2007) La localisation des immigrants en France: Une première approche. Revue d’Economie Régionale et Urbaine 4:625–649

Jayet H, Ukrayinchuk N, Arcangelis GD (2010) The location of immigrants in Italy: disentangling networks and local effects. Ann Econ Stat 97(98):329–350

Karemera D, Oguledo VI, Davis B (2000) A gravity model analysis of international migration to North America. Appl Econ 32(13):1745–1755

Le Bras H, Labbé M (1993) La planète au village: Migrations et peuplement en France. DATAR, La Tour d’Aigues: Editions de l’Aube

Lewer J, Van den Berg H (2008) A gravity model of immigration. Econ Lett 99(1):164–167

Magnusson L, Özüekren AS (2002) The housing careers of Turkish households in middle-sized Swedish municipalities. Hous Stud 17(3):465–486

Mayda A (2010) International migration: a panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. J Popul Stud 23:1249–1274

Mayer T, Mucchielli JL (1999) La localisation á l’étranger des entreprises multinationales: Une approche d’économie géographique hiérarchisée appliquée aux entreprises japonaises en Europe. Econ Stat 362:159–176

McFadden D (1978) Modelling the choice of residential location. Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California

Ortega F, Peri G (2012) The effect of income and immigration policies on international migration. Boston Working Paper NBER p 18322

Ottaviano G, Peri G (2012) Rethinking the effects of immigration on wages. J Eur Econ Assoc 10:152–197

Pedersen PJ, Pytlikova M, Smith N (2008) Selection and network effects—migration flows into OECD countries 1990–2000. Eur Econ Rev 52(7):1160–1186

Rapoport H, Docquier F (2006) Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity, vol 2, Elsevier, Amsterdam, North Holland, chap The economics of migrant’s remittances

Rebelo EM (2012) Work and settlement locations of immigrants: how are they connected? The case of the oporto metropolitan area. Eur Urban Reg Stud 19(3):312–328

Roux G (2004) L’évolution des opinions relatives aux étrangers: Le cas de la France. Informations Sociales 113

Ruyssen I, Everaert G, Rayp G (2014) Determinants and dynamics of migration to OECD countries in a three-dimensional panel framework. EMP Econ 46(1):175–197

Schönwälder K, Söhn J (2009) Immigrant settlement structures in Germany: general patterns and urban levels of concentration of major groups. Urban Stud 46(7):1439–1460

Scott DM, Coomes PA, Izyumov AI (2005) The location choice of employment-based immigrants among US metro areas. J Reg Sci 45(1):113–145

Simpson NB, Sparbert C (2013) The short- and long-run determinants of less-educated immigrant flows into U.S. states. Southern Econ J 80(2):414–438

Ukrayinchuk N, Jayet H (2011) Immigrant location and network effects: the Helvetic case. Int J Manpow 32(3):313–333

Vang ZM (2010) Housing supply and residential segregation in Ireland. Urban Stud 47(14):2983–3012

Winkelman R, Zimmerman K (1993) Labour markets in an ageing Europe, Chap Ageing, migration and labour mobility. Cambridge University Press, pp 225–287

Winters P, de Janvry A, Sadoulet E (2001) Family and community networks in Mexico-U.S. migration. J Hum Resour 36(1):159–184

Zavodny M (1997) Welfare and the locational choices of new immigrants. Econ Rev, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, pp 2–10

Zhu P, Yang Liu C, Painter G (2014) Does residence in an ethnic community help immigrants in a recession? Reg Sci Urban Econ 47:112–127

Acknowledgments

The authors are much indebted to comments on an earlier draft of this paper by two anonymous referees. We are grateful to participants to the “Economics of Global Interactions: New Perspectives on Trade, Factor Mobility and Development Conference” (Bari, 2011), “North American Regional Science Council Conference” (Miami, 2011), “Annual Conference of the European Regional Science Association” (Lausanne, 2011), “18th International Panel Data Conference” (Paris, 2012), “Norface Migration: Global Development, New Frontiers” (London, 2013) as well as research seminars at SHERPPA (Ghent University) and IRES (Université Catholique de Louvain). Responsibility for any remaining errors lies with the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.