Abstract

Purpose

To determine potential quadriceps versus hamstring tendon autograft differences in neuromuscular function and return to sport (RTS)-success in participants after an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

Methods

Case–control study on 25 participants operated on with an arthroscopically assisted, anatomic ipsilateral quadriceps femoris tendon graft and two control groups of 25 participants each, operated on with a semitendinosus tendon or semitendinosus-gracilis (hamstring) tendon graft ACL reconstruction. Participants of the two control groups were propensity score matched to the case group based on sex, age, Tegner activity scale and either the total volume of rehabilitation since reconstruction (n = 25) or the time since reconstruction (n = 25). At the end of the rehabilitation (averagely 8 months post-reconstruction), self-reported knee function (KOOS sum scores), fear of loading the reconstructed knee during a sporting activity (RSI-ACL questionnaire), and fear of movement (Tampa scale of kinesiophobia) were followed by hop and jump tests. Front hops for distance (jumping distance as the outcome) were followed by Drop jumps (normalised knee joint separation distance), and concluded by qualitative ratings of the Balanced front and side hops. Between-group comparisons were undertaken using 95% confidence intervals comparisons, effect sizes were calculated.

Results

The quadriceps case group (always compared with the rehabilitation-matched hamstring graft controls first and versus time-matched hamstring graft controls second) had non-significant and only marginal higher self-reported issues during sporting activities: Cohen’s d = 0.42, d = 0.44, lower confidence for RTS (d = − 0.30, d = − 0.16), and less kinesiophobia (d = − 0.25, d = 0.32). Small and once more non-significant effect sizes point towards lower values in the quadriceps graft groups in the Front hop for distance limb symmetry values in comparison to the two hamstring control groups (d = − 0.24, d = − 0.35). The normalised knee joint separation distance were non-significantly and small effect sized higher in the quadriceps than in the hamstring groups (d = 0.31, d = 0.28).

Conclusion

Only non-significant and marginal between-graft differences in the functional outcomes at the end of the rehabilitation occurred. The selection of either a hamstring or a quadriceps graft type cannot be recommended based on the results. The decision must be undertaken individually.

Level of evidence

III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

After an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture and reconstruction, neuromuscular performance, mostly rated by jump- or hop-performances and movement quality, are predictive for a subsequent second ACL injury [2, 11, 13]. Consequently, knowledge on neuromuscular performance is crucial when reconstruction-, rehabilitation- and return to sport-success is rated after an ACL reconstruction.

Semitendinosus (alone or in combination with gracilis; = hamstring) and quadriceps femoris tendon grafts show comparable graft survival rates, clinical stability and functional outcomes when compared to each other [14, 15]. In contrast functional outcomes, such as knee extensor muscle strength deficiency, might be superior in knees which were reconstructed with a hamstring graft than in those with a quadriceps graft [14, 22]. Although numerous randomised controlled and observational studies have compared quadriceps and hamstring grafts, little is known on potential differences between hamstring and quadriceps graft-based reconstructions on return to sport success rates.

In most studies on this topic, the comparative functional measurements were taken at pre-selected or randomly selected time points. As the duration until rehabilitation completion and return to sports success is highly variable between individuals [24], a comparison at the real end of the individual rehabilitation [27], and not at a hypothetical end or at a random point in time, might be more promising when the functional outcomes of a graft type selection should be compared. A comparison of individuals who were reconstructed with a quadriceps tendon graft to participants with both, a rehabilitation-volume matched and a time-matched hamstring graft, may be the most valid approach to compare functional outcomes and return to sport success between different grafts.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to compare self-reported and objective functional outcomes, as well as return to sport success, from participants after a quadriceps autograft reconstruction with both a rehabilitation volume-matched and a time-matched hamstring autograft group. We hypothesised that (1) the quadriceps group shows inferior self-report and (2) objective functional values than the hamstring autograft groups and that (3) no between-group differences in return to sport success rates between the groups occurs.

Materials and methods

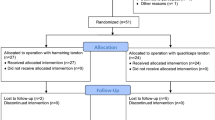

This propensity score matched case–control study was conducted as a part of the PReP project [17]. The independent Ethics Committee of the Hessen Regional Medical Council Ethical (reference approval no. FF 104/2017) and, subsequently, each centre’s responsible ethics committee provided approval. Each participant signed informed written consent for participating in the intervention study prior to enrolment.

The study was planned and performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki (Version Fortaleza 2013). The study was pre-registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS), 01. October 2018, DRKS00015313).

Participants

Individuals with an acute unilateral ACL rupture and having passed an arthroscopically assisted, anatomic ipsilateral quadriceps femoris or a hamstring tendon graft ACL reconstruction were included. Secondary inclusion criteria were (1) being < 36 years of age, (2) have been engaged in any type of sport prior to the ACL injury and (3) aimed to return to their previous sporting activity.

Exclusion criteria consisted of a meniscus lesion with a diameter of > 2 cm, (2) a cartilage lesion > ICRS II°, previous musculoskeletal surgery of the uninvolved (contralateral) leg, leg malalignment > 5°, a multi-ligament injury pattern, severe post-operative complications such as graft failure, arthrofibrosis, or a subsequent second knee injury, acute or chronic inflammation of the musculoskeletal system or muscle soreness and pregnancy.

Autograft selection

The autograft was selected based on biomechanical and individual criteria. When it was, from the athlete point of view of the participant and/or due to the type of activity, important to preserve the hamstring complex and, thus, to avoid damage to the knee flexor compartment [22], a quadriceps graft was usually selected. From a biomechanical point of view, small hamstring tendon sizes may not be suitable for a graft in certain patients [21].

Matching

To match two counterpart to each quadriceps graft participant, we screened all 229 participants with a hamstring graft and a measurement at the end of the individual rehabilitation included in the PReP-cohort [17]. A logistic regression propensity score, utilising a matching ratio of 1:1, was subsequently performed. For each participant in the quadriceps group, the matching procedure was performed twice. Once with the total volume of rehabilitation measures since reconstruction and once with the time since reconstruction as one of the matching variables. In both matching groups, the other matching variables were: sex, age and the pre-injury Tegner activity scale. As a result of this procedure, the two resulting comparator groups contained duplicate persons and should, therefore, not be compared to each other but only to the quadriceps group.

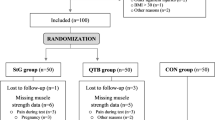

Sample

The quadriceps graft (case) sample consisted of n = 25 (12 females and 13 males, 25.8 ± 5.7 years) and, the hamstring graft (control) sample of n = 35 (17 females and 18 males, 24.4 ± 4.1 years) individual participants. N = 10 participants were included in both of the hamstring graft control groups.

Individual rehabilitation and measurement time point determination

To ensure that they were not only called just once at the hypothetical end of rehabilitation, all participants were prospectively monitored until their individual rehabilitation completion through a series of telephone calls [5]. The prescription of the individual medically prescribed rehabilitation followed a stepwise function-based periodisation and progression [4, 24, 26]. Restoring the knee range of motion was followed by a function-based progression to strengthening and neuromuscular motor control training. The decisions on rehabilitation completion were made based on the formal completion of the medically prescribed rehabilitation measures, the integration of the available evidence and guidelines, the stakeholders’ clinical experience and the athlete's own preferences [1]. More detailed, full knee range of motion compared with the uninjured side, minimal effusion present (trace or less), ability to hop on one leg without pain and participating in a running progression programme, and psychological readiness for RTS were the release criteria [27]. In addition, the participants had to be cleared for their sport-specific training components and for hopping on one leg by their treating orthopaedic surgeon and physical therapists [5]. Due to local and health-assurance differences, minor between-participant differences regarding the exact design and structuring of the rehabilitation measures may exist.

Measurements and outcomes

In the structured telephone interview at inclusion (at 1–3 weeks after the reconstruction), the participants reported socio-demographic and anthropometric details, injury mechanisms (contact free, indirect contact, direct contact), all (rehabilitation) measures taken between injury and reconstruction [8] and the pre-injury type(s) of sport and volume of training (recreational/low-level competitive, semi-professional [16], professional). Numerous surgery-specific outcomes were retrieved from the surgery report: autograft type (quadriceps femoris, semitendinosus, or semitendinosus-gracilis), tendon folding (from three times up to eight times) and the tendon diameter [mm].

The outcome assessments took place at the individually determined end of the rehabilitation and consisted of a battery of questionnaires, followed by a series of hop and jump tests. Knee function and symptoms were reported using the Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) subscales: sport (SPORT), pain (PAIN), symptoms (SYMPTOMS) and activities of all daily living (ADL). The KOOS thresholds/cut-offs for non-restricted ratings (“non-symptomatic”) were: PAIN 89 points, SYMPTOMS 83, ADL 95 and SPORT 72 points [18]. To report the potential fear of loading their reconstructed knee during a sporting activity, the participants completed the RTS after ACL injury questionnaire (RSI-ACL). For the ACL-RSI (11-point Likert scale), a total score value of > 56 indicates sufficient confidence for RTS [10]. Other self-reported outcomes were the Tegner activity scale to measure the participant’s sporting activity level and RTS and the Tampa scale of kinesiophobia (TSK), to measure their fear of movement. The volume, type, intensity and duration of all rehabilitation/sport/exercise measures undertaken since reconstruction were further assessed. When the same type and level of sport as that prior to the injury, irrespective of competition or training, was reached, the participant was treated as “RTS-successful” (yes/no at the time of the measurements). All these self-reported outcomes were collected in an online-survey on www.surveymonkey.de.

After a specific warm-up (jumping jacks and steps), the Front hop for distance (i.e. single leg hop for distance) was performed. The cut-off/threshold for the present case was selected to be an LSI of 90% for the Front hop for distance. The test conduction and measurement quality criteria can be found in the supplemental file 1.

The Drop jump screening test followed. A normalised knee separation distance at the jump’s reversal point of 60% was selected as the cut-off threshold for the following ratings and analyses [20]. The detailed test conduction and measurement quality criteria can be found in the supplemental file 1.

For the sagittal plane landing quality rating, the Balance front hop test [12] was performed. The frontal plane landing quality rating was undertaken using the Balance side hop test [12]. The test conduction and measurement quality criteria can be found in the Supplemental File 1.

All hop/jump tests were performed by self-administration and filmed from a frontal position (3 m distance). The participants used their own smartphone cameras. The videos were expert-rated using the investigator-blinded videos. Participants were educated on how to perform the jumps and hops. In cases of incorrect execution, the tests and, where needed, the instructions for the tests were repeated. This is valid when compared to 3D motion-capture systems for the analyses of sagittal plane knee angles [7].

Statistical analysis

The required sample size was estimated based on the effects for the self-reported sport-associated function (KOOS-SPORT) at a 1-year post-surgery follow-up [14]. The quadriceps group reached a mean value of 70 (standard deviation 23) points and the hamstring graft group of 76 (16) points. Adapted to a matched pairs-design (paired tests) with a suggested between matching-pairs correlation coefficient of 0.7 and the calculated Cohen’s dz of 0.36; at least 25 full datasets per group are needed to be included in the analyses if a significant result should be found under an 5% alpha and a 20% beta error probability. Thus, 25 participants with a quadriceps graft had to be recruited and 2 × 25 hamstring graft participants from the PReP cohort had to be included for matching purposes.

The alpha-error threshold was set at 5% for all inference statistical analyses The analyses were performed with SPSS (Version 28, IBM SPSS, USA).

Main between-graft comparisons for any interval scaled or pseudo-interval scaled outcomes were undertaken based on the means and 95% confidence intervals comparisons plus between group effect size comparisons. The confidence intervals were displayed separated by groups, while comparisons were undertaken using confidence intervals overlapping comparisons and by Cohen’s d comparisons between groups (quadriceps in comparisons to one of the hamstring groups at each time).

The numbers (and %) of the participants fulfilling the pre-defined and literature-based cut-offs, again separated by group, were displayed as absolute numbers. Inference-statistically, associations of RTS success and fulfilling the functional cut-offs were checked using Chi2-tests or the Fisher's exact test, depending on the structure. The groups were compared using relative risks (with 95% confidence intervals).

Explorative secondary analyses contained linear mixed models for repeated measures. The time effects were modelled as random effects (and factors), the other independent variables (group) and covariates (potential confounders and effect modifiers) as fixed effects.

Results

No participant was excluded, no one withdrew his/her consent for participation. No adverse events or serious adverse events occurred. All sport-, injury- and surgery-specific characteristics of the study sample can be found in Table 1.

The hamstring rehabilitation-matched group showed a significantly shorter time period since reconstruction than the quadriceps graft group (Additional Fig. 1A in the Supplement). In this period, the total volume of exercise (rehabilitation measures and sport) in minutes was significantly larger in the time-matched hamstring participants than in the quadriceps graft group individuals (Additional Fig. 1A in the Supplement).

Figure 1 displays the outcomes for the self-reported knee problems, as assessed by the KOOS questionnaire. Only marginal effect sized and non-significant differences between the quadriceps graft participants and either of the two hamstring matching groups occurred. In the self-reported problems during sporting activities (KOOS SPORT), the quadriceps graft group showed non-significantly higher values than the two hamstring control groups.

Self-reported knee problems. Data are displayed as individual values (dots) and as group means (horizontal lines) with 95%-confidence intervals (vertical lines). Effect sizes are displayed as Cohen’s d (d) with [95% confidence intervals]. KOOS The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, ADL activities of daily living

The between-graft comparison for the confidence to return to sport (ACL-RSI) and for kinesiophobia revealed no between-graft differences (Fig. 2). Small effect sizes hinting towards less (although, again, non-significant) confidence for return to sport and towards less kinesiophobia in the quadriceps graft than in the two hamstring graft groups occurred.

Self-reported knee confidence to return to sport and kinesiophobia. Data are displayed as individual values (dots) and as group means (horizontal lines) with 95%-confidence intervals (vertical lines). Effect sizes are displayed as Cohen’s d (d) with [95% confidence intervals]. ACL-RSI anterior cruciate ligament return to sport after injury questionnaire

In Fig. 3, the outcomes and between-graft comparisons for the Front hop for distance and for the Drop jump are displayed. No significant differences and only marginal to low effect sizes (favouring the two hamstring graft types in the Front hop and quadriceps graft participants in the Drop jump) were reached.

Results for the Front hop for distance (left part) and the Drop jump (as measured by the normalised knee separation distance, right), separated for the reconstructed (above) and contralateral (mid) leg, and for the limb symmetry index (below). Data are displayed as individual values (dots) and as group means (horizontal lines) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines). Effect sizes are displayed as Cohen’s d (d) with [95% confidence intervals]

Only marginal and non-significant differences between the quadriceps graft participants and either of the two hamstring matching groups occurred in the two balance hopping performances (Fig. 4). The hamstring participants showed marginal and not significantly larger between-leg differences in the Balance side hop and better values in the Balance front hop performance with the contralateral leg.

Results for the Balance hop tests, separated for the reconstructed (above) and contralateral (mid) leg, and for the limb symmetry index (below). Both the Balance side (left) and front hop (right) data are displayed as individual values (dots) and as boxplots with whisker bars, medians, and interquartile ranges

Only 16% in the quadriceps graft group returned to their pre-injury type and level of sport. In the hamstring graft groups, this share was (rehabilitation-matched group) 32% and (time-matched control) 38%). The underlying absolute values for this percentage share and the relative risk including its confidence intervals are, likewise, for all other self-reported and objectively assessed functional outcomes, displayed in the Table 2, likewise.

None of the outcomes was non-equally distributed between groups with the exception of the Balance front hop for the contralateral leg. Here, more participants of the quadriceps graft group than in the hamstring graft time-matched group had not reached the requested 5 points.

The results of the explorative linear mixed models can be found in the Supplemental Table 1. The graft type itself had a significant effect on knee problems during everyday functions; here, the quadriceps patients reported worse values (Supplemental Table 1). Furthermore, many co-variates such as age, time since reconstruction, having been rehabilitated during the COVID-associated restrictions, and the Tegner activity scale had a significant effect on the outcomes. In contrast, only minor non-significant interaction effects (co-variate*graft type) occurred: graft type* sex had a negative impact on kinesiophobia, whereas graft type*lockdown led to a decrease in both kinesiophobia and in the Front hop for distance limb symmetry index, likewise. Graft type*age significantly increased the normalised knee separation distance at landing.

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was the marginal differences in self-reported and objectively assessed function between participants with a quadriceps autograft reconstruction and those with hamstring autograft reconstructions. These marginal differences were independent of whether the hamstring control group was matched to the quadriceps graft case group in terms of rehabilitation amounts or in terms of time since reconstruction. Therefore, the hypotheses (1) and (2) must be rejected, while hypothesis (3) could be verified.

The participants completed their individual rehabilitation averagely at 8 months post-reconstruction. This value corresponds to reference studies in which the return to sport clearance in young, non-professional athletes was reached at 8.2 months post-surgery [23]. Thus, external validity of the sample seems to be given. The findings are consequently, generalizable to a young and physically active population following an isolated ACL tear and subsequent hamstring or quadriceps tendon graft reconstruction.

The non-significant and, according to the effects sizes, marginal differences between the quadriceps and hamstring-tendon grafts are in accordance with the current literature in the field [3, 22]. Neither in the self-reported functional ratings, such as the IKDC [3, 22], Tegner-, or Lysholm-score [22], nor in the objective functional outcomes, such as the Front hop for distance limb symmetry index [22], were between-graft type-differences frequent. Whilst the same picture is eminent for the knee flexor strength and hamstring to quadriceps strength ratios, the hamstring tendon autografts were associated with a better limb symmetry index in the knee extensor strength [22]. This may be a reason for the potential differences found in the present sample: in contrast to the Drop jump and Balance side hop performances, the Front hop for distance and the Balance front hop both need a sagittal plane deceleration with a major contribution from the knee extensors. The Drop jump, and, in particular, the Balance side hop do not need such a major contribution of the knee extensors. One must keep in mind that the results were non-significant and so the graft type discussion in this paper should be considered as explorative.

Sport-associated self-reported outcomes scores were, additionally, only slightly superior in the hamstring-graft groups, whereas the kinesiophobia values tended to be lower in the quadriceps group. An explanation for the latter finding may be found in the explorative analyses; the graft types may have acted differently during a lockdown in terms of kinesiophobia [19]. A smaller share of the quadriceps group than in the two hamstring graft groups performed their rehabilitation measures during restriction. Furthermore, as the COVID-associated restriction impacted on many psychosocial issues [6], kinesiophobia may also have been affected.

In general, upon individual rehabilitation completion, those participants with a rehabilitation-matched and those with a time-matched hamstring graft volume were not different than participants with a quadriceps tendon graft.

As only marginal between-graft differences in functional outcomes at the end of the rehabilitation occurred, the decision to selection of a hamstring or a quadriceps graft type cannot be undertaken based on the results. Beyond comparable functional findings of other studies, this conclusion is supported by findings of no differences in stability outcomes and in the odds for a Lachman test grade 0 differences between grafts at an early post-reconstruction time point [3, 22]. In contrast, the quadriceps autograft knees display significantly lower rates of donor site morbidity than the hamstring grafts, but higher knee extensor strength values [22]. It cannot, to sum up, be conclusively be recommended to use any of these two autografts based on the current literature. The decision must be undertaken individually. A small hamstring tendon size leads to the decision not to select a hamstring tendon as an autograft [22]. The need to avoid donor-site damages of the knee flexor, in, for example, in judokas and cyclists and of the knee extensors, in, for example, in hockey players, automatically excludes the respective tendons as a graft.

As only considerably low shares of the participants fulfilled all the functional cut-offs for a successful function at the end of their formal rehabilitation, the end of the rehabilitation is, thus, not the actual end of the rehabilitation [18]. One may conclude that either adding more sport-specific training or continuing rehabilitation exercises after the end of the medically prescribed formal rehabilitation measures may be required for recovery completion.

Future studies are warranted to determine potential differences in the trainability between the different graft types, both during rehabilitation itself at the early and late-stage, and during subsequent recurrence-preventive measures. A graft comparison in other samples such as adolescents or in older participants than ours would furthermore expand the transferability of the results.

From a pragmatic point of view and due to the research gap sketched above (the need for a rehabilitation- versus time-matching), a randomised controlled approach could not be adopted in the present study. Although meta-analyses found no significant differences in the effect estimates between the randomised controlled trials and observational studies [3], it still must be considered as a limitation.

In this study, only tests that were self-administered by the patient in view of the pandemic situation and the otherwise higher dropout rate were adopted; this approach was assumed to be the most practicable way. However, this setting may display a more vulnerable validity than laboratory measurements.

Although a state-of-the-art effect estimator was used, the LSI may overestimate one’s functional ability by masking bilateral deficits [9]. Recently, estimated pre-injury capacity levels (EPIC), instead of LSIs, were proposed to be more sensitive in predicting a second ACL injury [25].

By including 3 × 25 participants, the sample size calculation was followed; the analyses are, thus, considered as adequately powered. However, a larger sample size would have led to even more robust findings, although the clinical relevance of the (rather marginal and small effect [sizes]) still would question the clinical relevance of the between-graft differences.

Conclusions

Only marginal and non-significant differences in functional outcomes between quadriceps and hamstring autograft reconstructions occur after anterior cruciate ligament ruptures at the end of rehabilitation. The decision for selecting a hamstring tendon or a quadriceps tendon autograft cannot conclusively be recommended based on these functional outcomes but must be undertaken individually.

References

Ardern CL, Bizzini M, Bahr R (2016) It is time for consensus on return to play after injury. Five key questions. Br J Sports Med 50:506–508. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095475

Ashigbi EYK, Banzer W, Niederer D (2020) Return to Sport Tests’ prognostic value for reinjury risk after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 52:1263–1271. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002246

Dai W, Leng X, Wang J et al (2022) Quadriceps tendon autograft versus bone-patellar tendon-bone and hamstring tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 50:3425–3439. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465211030259

Diermeier TA, Rothrauff BB, Engebretsen L et al (2021) Treatment after ACL injury: panther symposium ACL Treatment Consensus Group. Br J Sports Med 55:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102200

Dingenen B, Gokeler A (2017) Optimization of the return-to-sport paradigm after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A critical step back to move forward. Sports Med 47:1487–1500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0674-6

Ernst M, Niederer D, Werner AM et al (2022) Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005

Finkbiner MJ, Gaina KM, McRandall MC et al (2017) Video movement analysis using smartphones (ViMAS): a pilot study. J Vis Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/54659

Giesche F, Niederer D, Banzer W et al (2020) Evidence for the effects of prehabilitation before ACL-reconstruction on return to sport-related and self-reported knee function: a systematic review. PLoS One 15:e0240192. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240192

Gokeler A, Welling W, Benjaminse A et al (2017) A critical analysis of limb symmetry indices of hop tests in athletes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a case control study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 103:947–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2017.02.015

Gokeler A, Welling W, Zaffagnini S et al (2017) Development of a test battery to enhance safe return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:192–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-4246-3

Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H et al (2016) Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med 50:804–808. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031

Keller M, Kurz E, Schmidtlein O et al (2016) Interdisciplinary assessment criteria for rehabilitation after injuries of the lower extremity: a function-based return to activity algorithm. (Interdisciplinary Assessment Criteria for Rehabilitation after Injuries of the Lower Extremity: a function-based return to activity algorithm). Sportverletz Sportschaden 30:38–49. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-100966

Kyritsis P, Bahr R, Landreau P et al (2016) Likelihood of ACL graft rupture. Not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med 50:946–951. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095908

Lind M, Nielsen TG, Soerensen OG et al (2020) Quadriceps tendon grafts does not cause patients to have inferior subjective outcome after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction than do hamstring grafts: a 2-year prospective randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 54:183–187. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101000

Mouarbes D, Menetrey J, Marot V et al (2019) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes for quadriceps tendon autograft versus bone-patellar tendon-bone and hamstring-tendon autografts. Am J Sports Med 47:3531–3540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518825340

Niederer D, Wilke J, Vogt L et al (2018) Return to play after injuries: a survey on the helpfulness of various forms of assistance in the shared decision-making process in semiprofessional athletes in Germany. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 99:690–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.10.019

Niederer D, Keller M, Achtnich A et al (2019) Effectiveness of a home-based re-injury prevention program on motor control, return to sport and recurrence rates after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: study protocol for a multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial (PReP). Trials 20:495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3610-2

Niederer D, Keller M, Wießmeier M et al (2022) The end of the formal rehabilitation is not the end of rehabilitation: knee function deficits remain after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Personal communication

Niederer D, Mengis N, Wießmeier M et al (2023) Contributors to self-report motor function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sci Rep 13:3073. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30291-x

Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Fleckenstein C et al (2005) The drop-jump screening test: difference in lower limb control by gender and effect of neuromuscular training in female athletes. Am J Sports Med 33:197–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546504266484

Offerhaus C, Albers M, Nagai K et al (2018) Individualized anterior cruciate ligament graft matching: in vivo comparison of cross-sectional areas of hamstring, patellar, and quadriceps tendon grafts and ACL insertion area. Am J Sports Med 46:2646–2652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518786032

Tan TK, Subramaniam AG, Ebert JR et al (2021) Quadriceps tendon versus hamstring tendon autografts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465211033995

Toole AR, Ithurburn MP, Rauh MJ et al (2017) Young athletes cleared for sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how many actually meet recommended return-to-sport criterion cutoffs? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 47:825–833. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7227

van Melick N, van Cingel REH, Brooijmans F et al (2016) Evidence-based clinical practice update: practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. Br J Sports Med 50:1506–1515. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095898

Wellsandt E, Failla MJ, Snyder-Mackler L (2017) Limb symmetry indexes can overestimate knee function after anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 47:334–338. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7285

Wilk KE, Arrigo CA (2017) Rehabilitation principles of the anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knee. twelve steps for successful progression and return to play. Clin Sports Med 36:189–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csm.2016.08.012

Zarzycki R, Arhos E, Failla M et al (2021) Association of the psychological response to the ACL-SPORTS Training Program and self-reported function at 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 49:3495–3501. https://doi.org/10.1177/03635465211045388

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The study was supported by a grant from the German Knee Society (DKG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

Ethics Committee of the Hessen Regional Medical Council (reference approval no. FF 104/2017) and secondarily by each centre’s responsible ethics committee. Date of the final approval of the study protocol was 27th June, 2018.

Informed consent

Yes. All participants signed informed written consent for participating in the intervention study prior to enrolment.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niederer, D., Keller, M., Jakob, S. et al. Quadriceps and hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction differ only marginally in function after the rehabilitation: a propensity score-matched case–control study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31, 3441–3453 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07422-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07422-y