Abstract

Purpose

Medial bicompartmental arthroplasty, the combination of ipsilateral medial unicompartmental and patellofemoral arthroplasty, is an alternative to total knee arthroplasty for patients with medial tibiofemoral and severe patellofemoral arthritis, when the lateral tibiofemoral compartment and anterior cruciate ligament are intact. This study reports the gait and subjective outcomes following medial bicompartmental arthroplasty.

Methods

Fifty-five subjects were measured on the instrumented treadmill at top walking speeds, using standard metrics of gait. Modular, single-stage, medial bicompartmental arthroplasty subjects (n = 16) were compared to age, body mass index, height- and sex-matched healthy (n = 19) and total knee arthroplasty (n = 20) subjects. Total knee arthroplasty subjects with pre-operative evidence of tricompartmental osteoarthritis or anterior cruciate ligament dysfunction were excluded. The vertical component of ground reaction force and temporospatial measurements were compared using Kruskal–Wallis, then Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05). Oxford Knee and EuroQoL EQ-5D scores were compared.

Results

Objectively, the medial bicompartmental arthroplasty top walking speed of 6.7 ± 0.8 km/h was 0.5 km/h (7%) slower than that of healthy controls (p = 0.2), but 1.3 km/h (24%) faster than that of total knee arthroplasty subjects (5.4 ± 0.6 km/h, p < 0.001). Medial bicompartmental arthroplasty recorded more normal maximum weight acceptance (p < 0.001) and mid-stance forces (p = 0.03) than total knee arthroplasty subjects, with 11 cm (15%) longer steps (p < 0.001) and 21 cm (14%) longer strides (p = 0.006). Subjectively, medial bicompartmental arthroplasty subjects reported Oxford Knee Scores of median 41 (interquartile range 38.8–45.5) compared to total knee arthroplasty Oxford Knee Scores of 38 (interquartile range 30.5–41, p < 0.02). Medial bicompartmental arthroplasty subjects reported EQ-5D median 0.88 (interquartile range 0.84–0.94) compared to total knee arthroplasty median 0.81 (interquartile range 0.73–0.89, p < 0.02.)

Conclusion

This study finds that, in the treatment of medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis with severe patellofemoral arthritis, medial bicompartmental arthroplasty results in nearer-normal gait and improved patient-reported outcomes compared to total knee arthroplasty.

Level of evidence

III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introductions

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remains the gold-standard treatment for osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee, with widely reported success. Relative to TKA, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is associated with more normal gait [21, 35], higher satisfaction [26] and fewer peri- and post-operative serious complications [25], but significantly higher revision rates [1, 23]. There is limited evidence for multi-compartment PKA.

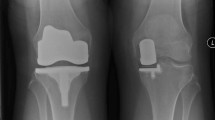

Of those undergoing primary knee arthroplasty, 23% have medial tibiofemoral and patellofemoral (PFJ) OA, with a spared lateral compartment [31]. Medial bicompartmental arthroplasty (BCA-M), the combination of ipsilateral medial UKA and patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA), is a bone, meniscus and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-preserving alternative to TKA (Fig. 1) [12, 14]. This study seeks to understand the gait characteristics and patient-reported outcomes of BCA-M compared to patients treated with a posterior- cruciate retaining TKA. The null hypothesis is that there are no differences between BCA-M and TKA in these parameters.

Materials and methods

A previous instrumented treadmill study compared the top walking speed of UKA-M (n = 12) to healthy controls (n = 121) and TKA (n = 12) [21]. UKA TWS was 7.9 km/h, similar to healthy subjects (TWS 7.9 km/h) but 37% faster than TKA (5.76 km/h). We assumed that the TKA subjects in our study would not differ significantly from previous studies, but predicted that BCA-M may walk up to 15% faster (TWS 6.63 km/h, 15% faster). A power calculation indicated that a minimum of 14 subjects per implant group would be necessary to detect such differences with 80% power and 95% confidence.

Potential subjects were retrospectively identified from the operative database of the senior author, between 2009 and 2019. Of 3090 knee arthroplasty procedures, 69 patients had undergone primary modular BCA-M. Subjects were excluded if they had a contralateral TKA in situ (n = 4, Fig. 2, Supplementary Table A); if they had undergone significant ipsilateral limb surgery pre- or post-BCA-M (n = 8), which included two subjects who had been revised following BCA-M; were over 85 years (n = 13); medically unfit (n = 6) or deceased (n = 10); or if they declined (n = 4) or were uncontactable (n = 6). After 53 exclusions (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table A), 16 BCA-M patients entered the study.

Matching

With institutional review board approval from NRES Committee South Central and the Academic Health Science Centre, Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, UK, our group prospectively evaluated healthy subjects and the patients of three senior arthroplasty surgeons on an instrumented treadmill (Kistler Gaitway, Kistler Instrument Corporation, Amherst, NY), over the past 9 years. Data were collected by a research assistant blinded to arthroplasty status. For the current study, the database was searched to identify suitable control subjects for comparison to the BCA-M group. At the time of data analysis, 19 healthy subjects matched to the age, body mass index (BMI) and sex of the BCA-M group (Table 1, Fig. 2). Forty-nine posterior-cruciate retaining TKA subjects were identified in the database. Potential TKA subjects were excluded if they had been measured prior to scheduled revision surgery (n = 5); had an ipsilateral hip replacement in situ (n = 2); had significant OA of the contralateral knee (n = 9); tricompartmental OA graded Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) ≥ 2 or evidence of ACL deficiency (n = 5), defined by > 7 mm anterior tibial translation on pre-operative radiographs [9]. The remaining TKA subjects underwent age, sex and body mass index matching (IBM® SPSS® Version 27, Table 1) resulting in 22 potential posterior-cruciate retaining TKA subjects. Since all BCA-M subjects had undergone patellar resurfacing, a further two TKA subjects were excluded, since they had not undergone patellar resurfacing. Consequently, 20 posterior-cruciate retaining TKA subjects entered the study, of whom 11 had single-compartment disease (medial n = 8, lateral n = 3). The remaining had two-compartment disease (medial and lateral n = 8, lateral with patellofemoral n = 1). TKAs were mean 40.6 ± 43 months post-surgery, 19.6 months longer than primary BCA-M (21 ± 18) though this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.1). The median months post-surgery were BCA-M 12.5 months (range 6–65 months) compared to TKA, 19.5 months (range 6–147 months, p = 0.5).

Treadmill testing

All subjects walked at 4 km/h for 2 min to acclimatize to the treadmill, before increasing speed in 0.5 km/h increments to their ‘top walking speed’ (TWS) defined as their fastest comfortable speed, or the highest walking speed before breaking into a run. Subjects walked, on average, for 12 min continuously, without the assistance of the hand safety rail. All subjects completed the test comfortably. Two tandem force plates, beneath the moving belt, recorded the vertical component of the ground reaction forces, temporospatial measurements and centre of pressure for both limbs, sampling at 100 Hz frequency over 10 s. To correct for differences in leg length and body mass, data were normalized post-collection using Hof scaling [20] and normalization of body weight (BW = ground reaction force/(body mass/gravity)) respectively.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Arthroplasty subjects were asked to complete the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and EuroQoL EQ-5D 5L Score at the time of their treadmill assessment.

Statistical analysis

TKA and healthy subjects were matched to the BCA-M cohort in IBM® SPSS® Version 27 for age (p = 0.3), sex (p = 1), body mass index (p = 0.9) and height (p = 0.5) from the prospectively collected database (Table 1). Gait output data were averaged using a custom MathWorks® MatLab® script and analysed in IBM® SPSS® Version 27. The Shapiro–Wilk test demonstrated that a number of variables were not normally distributed; therefore, all variables were compared using Kruskal–Wallis, then Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni correction where differences were detected. Significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Top walking speeds

Objectively, the medial bicompartmental arthroplasty top walking speed of 6.7 ± 0.8 km/h was 0.5 km/h (7%) slower than that of healthy controls (p = 0.16, Table 1, Fig. 3), but 1.3 km/h (24%) faster than that of total knee arthroplasty subjects (5.4 ± 0.6 km/h, p < 0.001). The TKA group walked 25% slower than healthy subjects (p < 0.001). The differences remained apparent after Hof scaling for leg length (Table 1).

Vertical ground reaction forces

At top walking speeds, compared to healthy subjects, both arthroplasty groups recorded reduced weight acceptance, though the differences did not reach significance (p > 0.05, Table 1, Fig. 4). BCA-M and healthy subjects recorded similar maximum weight acceptance force (p = 0.051), whilst in TKA subjects it was reduced (p < 0.001). During mid-stance, both groups recorded higher forces than the healthy cohort (p < 0.03); however, the BCA-M subjects were nearer normal, with a significant advantage over the TKA group (p < 0.03). All groups were similar in terms of push-off force and rate (p = 1). Compared to healthy and BCA-M subjects, TKA subjects recorded reduced cadence (p < 0.003, Table 1), increased double support time (Vs BCA-M p = 0.03) and increased contact time (p < 0.003). BCA-M subjects displayed nearer-normal temporospatial characteristics, with differences failing to reach significance when compared to healthy controls.

Step and stride lengths

BCA-M subjects’ median step lengths were similar to those of healthy subjects (both 82 cm), whilst those of TKA subjects were median 12 cm (15%) shorter (Fig. 5). This reflected the differences in stride length, whereby median BCA-M stride lengths were 167 cm (IQR 149-175 cm), 3 cm (2%) longer than those of healthy subjects, while TKA stride lengths were median 142 cm, 22 cm (13%) shorter than those of healthy subjects (Fig. 5).

Satisfaction and quality of life

OKS and EQ-5D scores were completed by all arthroplasty subjects. For the OKS, median scores were significantly higher for BCA-M than TKA (41 vs 38, p = 0.02, Fig. 6, Table 1). Though not validated by individual question, it is noteworthy that BCA-M scored equal to or higher than TKA in all questions of the OKS, with significant differences seen in the use of transport, chair rising, kneeling, instability symptoms and stair descent (all p < 0.03, Table 2). Similarly, median EQ-5D values were higher for BCA-M compared to TKA (0.88 vs 0.81. p < 0.02, Fig. 6, Table 1). BCA-M subjects recorded scores closer to 1 in every domain, reaching significance in mobility, usual activities and pain (p < 0.02, Table 3).

Discussion

This study finds that BCA-M has advantages over TKA in terms of gait and patient-reported outcomes, leading to the null hypothesis being rejected.

Severe lateral facet PFJ OA is considered by many to be a relative contraindication to medial UKA [4, 5], leading to TKA in the majority of these patients [1, 23]. In those with isolated medial with patellofemoral wear, TKA necessitates resection of healthy lateral bone, menisci, and a functional ACL. BCA-M may be considered appropriate for those with medial tibiofemoral and severe patellofemoral arthrosis (KL ≥ 2), with correctable varus, anterior–posterior sagittal stability and medial collateral ligament sufficiency (Table 4).

BCA-M has documented clinical success in the short and medium term [11, 19, 30] and is thought to restore isokinetic quadriceps function [33], whilst preserving near-native extensor efficiency [13]. There is some evidence that BCA-M results in higher function during strenuous activity [28], but no studies to our knowledge have compared BCA-M to healthy controls and TKA at top walking speeds. Arthroplasty performance can be objectively assessed using gait analysis on the instrumented treadmill. Previous studies have reported an advantage of UKA-M over TKA at top walking speeds [18, 21, 35] which the current study suggests is preserved following primary modular BCA-M, most notably in top walking speeds and stride length [21, 35]. Previous BCA-M gait studies have focused on historic monolithic BCA-M designs, some of which were blighted by high revision rates. These studies included fewer BCA-M subjects walking at slower walking speeds to those investigated here [24, 34].

The marked difference in top walking speed between BCA-M and TKA is particularly important. For every 0.1 m per second increase in top walking speed, life expectancy improves significantly and may be considered a proxy measure for a subject’s global post-operative health [32]. BCA-M is more anterior–posterior stable than TKA [15] where ACL resection can result in paradoxical anterior–posterior tibial translation, limiting mid-swing flexion and impacting stride length and walking speed [22]. Unlike TKA, BCA-M preserves extensor efficiency at the low flexion angles associated with gait [13], which may in part explain why differences are seen during maximum weight acceptance and mid-stance when the quadriceps are active.

Survivorship of primary BCA-M is largely unknown. The National Joint Registry has reported that primary multi-compartmental arthroplasty has a similar revision rate to primary patellofemoral arthroplasty, though the numbers are small and include all compartmental combinations, not just BCA-M [2]. Of the 69 primary BCA-M subjects considered for this study, two knees (3%) had been revised (Fig. 2, Supplemental Table A), one to a tricompartmental arthroplasty through the addition of a lateral UKA (Revision Partial Knee Classification PR2b [17]), 7 years after primary BCA-M, and one to a posterior-cruciate retaining TKA (Revision Partial Knee Classification PR3), performed at another hospital for unexplained pain after 4 years. Of the subjects included in the study, no subjects have since been revised.

Progressive arthritis remains a common mode of failure following single-compartment PKA [2, 6, 7]. The ‘compartmental approach’ (Revision Partial Knee Classification PR2b [17]) advocates the addition of a second PKA to the newly degenerate compartment, while retaining the primary PKA and ACL [14, 18]. It has been shown to preserve healthy gait characteristics, despite second surgery [16], reflecting the results of the present study.

The study was powered for gait analysis, with OKS and EQ-5D 5L scores collected as secondary outcome measures, though the study was underpowered for PROMs. Overall satisfaction and quality of life was good after both BCA-M and TKA, but a statistical advantage was reported following BCA-M. The difference in mean OKS exceeded the reported minimal important clinical difference of five points [3], though the difference in median OKS scores did not (Table 1). This suggests that there may be an advantage in PROMs with BCA-M, compared to this relatively satisfied cohort of TKAs. The recorded OKS and EQ-5D scores are similar to widely reported literature values for UKA and TKA [8, 26, 36], with no apparent adverse effect as a consequence of the additional PFA in BCA-M subjects when compared to medial UKA, supporting the findings of others [29]. Higher satisfaction is also reported in those revised through a compartmental approach [16]. The significant differences observed on the OKS in relation to rising from a chair, kneeling down, stair descent and instability symptoms support the theory that BCA-M preserves isokinetic quadriceps strength and anterior–posterior stability, known to be compromised following TKA [13, 15, 27].

This study would have benefited from pre-operative data to determine the extent of improvement each subject experienced as a consequence of surgery. However, attempts were made to mitigate its absence by only selecting TKA patients who underwent surgery for single- or two-compartment disease, did not have pre-operative evidence of ACL dysfunction, and would have been eligible for PKA or CPKA under the senior author’s current clinical practice. The inclusion of patients with single-compartmental disease in the TKA group was necessary to power the study, but may have acted to the detriment of the BCA-M group, who all had bicompartmental disease pre-operatively.

Clinical relevance

The retention of the lateral compartment and the cruciate ligament complex may play an important role in allowing patients with a BCA-M to retain near normal stride length and speed following surgery. The data may help clinicians and their patients when deciding on alternatives to TKA where once the benefits may have been considered unsubstantiated [10].

Conclusions

This study finds that, in the treatment of medial tibiofemoral osteoarthritis with severe patellofemoral arthritis, medial bicompartmental arthroplasty results in nearer-normal gait and improved patient-reported outcomes compared to total knee arthroplasty.

References

Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A, Boulton C, Brittain R, Clark E, Craig R et al (2019) National joint registry annual reports. The national joint registry 16th annual report 2019. National Joint Registry, London

(2021) 18th annual report. National Joint Registry

Beard DJ, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray DW, Carr AJ et al (2015) Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 68:73–79

Beard DJ, Pandit H, Gill HS, Hollinghurst D, Dodd CA, Murray DW (2007) The influence of the presence and severity of pre-existing patellofemoral degenerative changes on the outcome of the Oxford medial unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Br 89:1597–1601

Beard DJ, Pandit H, Ostlere S, Jenkins C, Dodd CA, Murray DW (2007) Pre-operative clinical and radiological assessment of the patellofemoral joint in unicompartmental knee replacement and its influence on outcome. J Bone Jt Surg Br 89:1602–1607

Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ, Sheinkop MB, Valle CJD, Rosenberg AG et al (2005) Results of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Jt Surg Am 87:999–1006

Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Sheinkop MB, Della Valle CJ, Jacobs JJ, Rosenberg AG et al (2004) The progression of patellofemoral arthrosis after medial unicompartmental replacement: results at 11 to 15 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000147700.89433.a592-99

Burn E, Sanchez-Santos MT, Pandit HG, Hamilton TW, Liddle AD, Murray DW et al (2018) Ten-year patient-reported outcomes following total and minimally invasive unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a propensity score-matched cohort analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:1455–1464

Chiu SS (2006) The anterior tibial translocation sign. Radiology 239:914–915

Cobb JP (2014) Patient safety after partial and total knee replacement. Lancet 384:1405–1407

Confalonieri N, Manzotti A, Cerveri P, De Momi E (2009) Bi-unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty: a matched paired study with early clinical results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129:1157–1163

Garner A, Cobb J (2020) Combined partial knee arthroplasty. In: Rivière C, Vendittoli P-A (eds) Personalized hip and knee joint replacement. Springer, Cham, pp 243–254

Garner A, Dandridge O, Amis AA, Cobb JP, van Arkel RJ (2021) The extensor efficiency of unicompartmental, bicompartmental, and total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt Res 10:1–9

Garner A, van Arkel RJ, Cobb J (2019) Classification of combined partial knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt J 101:922–928

Garner AJ, Dandridge OW, Amis AA, Cobb JP, van Arkel RJ (2021) Partial and combined partial knee arthroplasty: greater anterior-posterior stability than posterior cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2021.06.025

Garner AJ, Dandridge OW, van Arkel RJ, Cobb JP (2021) The compartmental approach to revision of partial knee arthroplasty results in nearer-normal gait and improved patient reported outcomes compared to total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06691-9

Garner AJ, Edwards TC, Liddle AD, Jones GG, Cobb JP (2021) The revision partial knee classification system: understanding the causative pathology and magnitude of further surgery following partial knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt Open 2:638–645

Haddad FS, Masri BA (2019) Compartmental arthroplasty: time for a clear nomenclature. Bone Jt J 101:889–890

Heyse TJ, Khefacha A, Cartier P (2010) UKA in combination with PFR at average 12-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 130:1227–1230

Hof AL (1996) Scaling gait data to body size. Gait Posture 4:222–223

Jones GG, Kotti M, Wiik AV, Collins R, Brevadt MJ, Strachan RK et al (2016) Gait comparison of unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasties with healthy controls. Bone Jt J 98:16–21

Kirtley C, Whittle MW, Jefferson RJ (1985) Influence of walking speed on gait parameters. J Biomed Eng 7:282–288

Klasan A, Parker DA, Lewis PL, Young SW (2021) Low percentage of surgeons meet the minimum recommended unicompartmental knee arthroplasty usage thresholds: analysis of 3037 Surgeons from Three National Joint Registries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06437-7

Leffler J, Scheys L, Plante-Bordeneuve T, Callewaert B, Labey L, Bellemans J et al (2012) Joint kinematics following bi-compartmental knee replacement during daily life motor tasks. Gait Posture 36:454–460

Liddle AD, Judge A, Pandit H, Murray DW (2014) Adverse outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee replacement in 101,330 matched patients: a study of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet 384:1437–1445

Liddle AD, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray DW (2015) Patient-reported outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study of 14,076 matched patients from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Bone Jt J 97:793–801

Lundberg HJ, Rojas IL, Foucher KC, Wimmer MA (2016) Comparison of antagonist muscle activity during walking between total knee replacement and control subjects using unnormalized electromyography. J Arthroplasty 31:1331–1339

Palumbo BT, Henderson ER, Edwards PK, Burris RB, Gutierrez S, Raterman SJ (2011) Initial experience of the Journey-Deuce bicompartmental knee prosthesis: a review of 36 cases. J Arthroplasty 26:40–45

Parratte S, Ollivier M, Opsomer G, Lunebourg A, Argenson JN, Thienpont E (2015) Is knee function better with contemporary modular bicompartmental arthroplasty compared to total knee arthroplasty? Short-term outcomes of a prospective matched study including 68 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 101:547–552

Parratte S, Pauly V, Aubaniac JM, Argenson JN (2010) Survival of bicompartmental knee arthroplasty at 5 to 23 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:64–72

Stoddart JC, Dandridge O, Garner A, Cobb J, Arkel R (2020) The compartmental distribution of knee osteoarthritis—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil 5:45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.011

Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K, Rosano C, Faulkner K, Inzitari M et al (2011) Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 305:50–58

Thienpont E, Price A (2013) Bicompartmental knee arthroplasty of the patellofemoral and medial compartments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21:2523–2531

Wang H, Foster J, Franksen N, Estes J, Rolston L (2018) Gait analysis of patients with an off-the-shelf total knee replacement versus customized bi-compartmental knee replacement. Int Orthop 42:805–810

Wiik AV, Manning V, Strachan RK, Amis AA, Cobb JP (2013) Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty enables near normal gait at higher speeds, unlike total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 28:176–178

Williams DP, Blakey CM, Hadfield SG, Murray DW, Price AJ, Field RE (2013) Long-term trends in the Oxford knee score following total knee replacement. Bone Jt J 95:45–51

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Royal College of Surgeons of England, Dunhill Medical Trust, Sir Michael Uren Foundation, Wellcome Trust.

Funding

This work was funded by the Sir Michael Uren Foundation; The Royal College of Surgeons of England and the Dunhill Medical Trust Clinical Research Fellowship. Infrastructure support was provided by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The instrumented treadmill was provided by The Centre of Excellence in Medical Engineering funded by the Wellcome Trust and EPSRC under grant number WT 088844/Z/09/Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJG: conception of the work, study design, execution of the study including acquisition of the data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing; OWD: data analysis and interpretation, manuscript editing/review; RJA: data analysis, manuscript review/editing; JPC: conception of the work, clinical cases, study design, execution of the study including acquisition of the data, data review, manuscript review/editing/revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Garner also reports research grants from Dunhill Medical Trust, RCS England, and the Sir Michael Uren Foundation for this study. R. van Arkel reports a research support grant from DePuy Synthes. J. Cobb reports board membership on Orthonika, consultancy payments from JRI, an institutional grant from DePuy Synthes, payment for lectures from Ceramtex, a patent and stocks from Embody, and royalties from Matortho, all unrelated to this study.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted with full ethical approval. Data were collected in the gait laboratory with Institutional Review Board approval from NRES Committee South Central - Oxford B, Study title: 3D and 2D Motion Capture Gait Analysis of Lower Limb Orthopaedic Patients. REC reference: 14/SC/1243. IRAS project ID: 136430 and from the Academic Health Science Centre, Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. Project Title: Gait Analysis Using An Instrumented Treadmill. Joint Research Office Reference number: JROHH0208. Ethics Reference number: 10/H0807/101.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garner, A.J., Dandridge, O.W., van Arkel, R.J. et al. Medial bicompartmental arthroplasty patients display more normal gait and improved satisfaction, compared to matched total knee arthroplasty patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31, 830–838 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06773-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06773-8