Abstract

Purpose

Surgeons may attempt to strip the posterior capsule from its femoral attachment to overcome flexion contracture in total knee arthroplasty (TKA); however, it is unclear if this impacts anterior–posterior (AP) laxity of the implanted knee. The aim of the study was to investigate the effect of posterior capsular release on AP laxity in TKA, and compare this to the restraint from the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).

Methods

Eight cadaveric knees were mounted in a six degree of freedom testing rig and tested at 0°, 30°, 60° and 90° flexion with ± 150 N AP force, with and without a 710 N axial compressive load. After the native knee was tested, a deep dished cruciate-retaining TKA was implanted and the tests were repeated. The PCL was then cut, followed by releasing the posterior capsule using a curved osteotome.

Results

With 0 N axial load applied, cutting the PCL as well as releasing the posterior capsule significantly increased posterior laxity compared to the native knee at all flexion angles, and CR TKA states at 30°, 60° and 90° (p < 0.05). However, no significant increase in laxity was found between cutting the PCL and subsequent PostCap release (n.s.). In anterior drawer, there was a significant increase of 1.4 mm between cutting the PCL and PostCap release at 0°, but not at any other flexion angles (p = 0.021). When a 710 N axial load was applied, there was no significant difference in anterior or posterior translation across the different knee states (n.s.).

Conclusions

Posterior capsular release only caused a small change in AP laxity compared to cutting the PCL and, therefore, may not be considered detrimental to overall AP stability if performed during TKA surgery.

Level of evidence

Controlled laboratory study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In total knee arthroplasty (TKA), the knee may be found to be too stiff in extension, causing an extension deficit. Being unable to fully extend the knee requires continuous quadriceps contraction during daily routine movements or standing, leading to tiredness and reduced function [14, 19, 24]. One proposed surgical technique to correct this flexion contracture is resecting additional bone from the distal femur, but that may lead to raising the joint line [20]. Whiteside and Milhalko determined that after removing osteophytes, the primary step should be collateral ligament release and a secondary step being posterior capsular release, with distal femoral cuts only considered if still uncorrected [17, 23]. It was previously believed that releasing the PCL could correct flexion contracture, but this has been found experimentally to increase the flexion gap relative to the extension gap and thus is counterproductive [16]. Alternatively, full extension may be gained by releasing the posterior capsule from its femoral attachment [4, 5, 12, 17]. However, if there was an adverse effect on anterior–posterior (AP) stability by releasing the capsule, then it may be advisable to avoid this and instead recut the femur.

LaPrade et al. [15] described the posterior aspect of the knee with the following anatomy: the semimembranosus muscle with eight distinct soft tissue attachments distal to the main tendon (including a lateral expansion to the oblique popliteal ligament); a posterior capsular thickening which extends from the popliteus musculotendinous junction to the posterior aspect of the intercondylar notch; a popliteofibular ligament and a fabellofibular ligament. However, the biomechanical function of this network of structures is not well understood. It is known, for example, that the oblique popliteal ligament restrains against knee hyperextension [18]; however, its importance to stability particularly in AP drawer is unknown. Gollehon et al. [9] found the posterolateral arcuate complex to be a secondary posterior stabiliser, but did not investigate the posterior capsule in detail. Furthermore, the meniscofemoral ligaments have been found to be secondary posterior drawer restraints [10]; therefore, it is unclear whether in the TKA setting (when the meniscus is resected) other posterior structures may become more important to stability. Recent robotic studies of TKA stability have investigated both the constraint of the implant and the effects of soft tissue releases [2, 3], but did not examine posterior capsular releases.

The primary aim of the study was to investigate if releasing the posterior capsule in an implanted knee caused a large increase in AP laxity which would, therefore, invalidate the use of the technique in TKA surgery. The null hypothesis was that releasing the posterior capsule would not increase laxity when the PCL had been previously cut.

Materials and methods

Eight fresh-frozen human cadaveric legs (six male and two female) of mean age 78 (standard deviation ± 10 years) were obtained from a tissue bank (four left-sided and four right-sided). The legs had been disarticulated through the hip, and were MRI and X-ray imaged ready for ‘patient’-specific TKA cutting guides. The knees were separated by cutting 170 mm from the joint line both distally on the tibia/fibula and proximally on the femur. The fibula was fixed to the tibia in an anatomic position with a distal tricortical bone screw. The tibia was then cemented in a 60-mm-diameter cylindrical steel pot with polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA, Simplex, Kemdent, UK). The joint capsule was opened with a midline skin incision and a medial parapatellar arthrotomy, then a jig with a pointer was used to align the centre of the tibial plateau (between the tips of the tibial spines) with the axis of the bone pot [1]. The femur was cemented using PMMA in a bone pot secured in situ in the testing rig, so that it was aligned with the knee in full extension and the posterior condylar axis parallel to the base of the rig.

Testing rig

A purpose-built rig was designed to be used in conjunction with a materials testing machine (Model 5565, Instron Ltd, High Wycombe, UK). The tibia was mounted in a fixture attached to the moving crosshead of the Instron, whilst the femur was mounted in a pivot frame on linear bearings (Fig. 1). The Instron applied an AP force/displacement to the tibia mounted in the rig at a fixed angle of flexion, whilst the other degrees-of-freedom were unconstrained and free to translate/rotate. The pivot point of the femoral frame could be adjusted medially–laterally to vary the load distribution between the medial and lateral knee compartments; in this study the knees were maintained at a medial:lateral loading distribution of 60:40 throughout testing [25]. To simulate a weight-bearing compressive load on the tibia, a pneumatic cylinder applied a 710 N force in the axial direction [11].

Test protocol

The native, intact knee with bone pots was mounted into the test rig. The knee was manually flexed 20 times to minimise soft tissue hysteresis, then a ± 150 N AP force was applied when the knee was at full extension, 30°, 60° and 90° flexion. ±150 N was chosen in line with a previously published recommendation on AP laxity testing on cadaveric knees [6]. Three pre-conditioning AP cycles were applied and the resulting AP force versus translation data (directly read from the materials testing machine with accuracy ± 0.1 mm and ± 0.5 N) were collected on the fourth cycle. A previous study demonstrated an intra-rater repeatability of the test rig as a 95% confidence interval of 1 mm [11].

To find the neutral AP position of the knee at each angle, a starting position approximated by eye was chosen, and a ± 3 mm AP draw was applied. The true neutral AP position was then defined at the point of inflection of the force–displacement hysteresis loop, when it was symmetrical above and below the zero force axis.

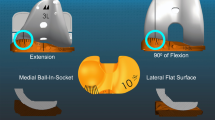

After the native knee was tested, a deep dished CR TKA (Legion, Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) was implanted by an experienced consultant surgeon using a medial parapatellar approach. During pilot studies, it was found that a standard high-flexion CR TKA subluxed anteriorly before reaching 150 N at 60° and 90° and, therefore, it was decided that a more congruent insert would be more appropriate. Femoral and tibial cuts were made using patient-specific guides (Visionaire, Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) based on the MRI and X-ray images taken prior to testing. 9.5 mm was resected from the distal femur (referenced from the most distal side of the femur) to account for the thickness of the implant, and 9 mm of bone from the proximal tibia, respectively (referenced from the most superior aspect of the tibial surface) to allow for the thinnest available polyethylene tibial insert (9 mm) to be used. The posterior tibial slope was set at 3 degrees to account for the slope already built into the articular insert. The tibial implant was cemented to the bone, whereas the femoral component was press-fit. This press-fit has previously been shown to give secure fixation at experimental loads [7]. The following stages were sequentially performed and tested at full extension, 30°, 60° and 90° knee flexion with ± 150 N AP force, both with and without 710 N axial loads:

-

1.

The native, intact knee was tested.

-

2.

The CR TKA was implanted with a deep dished insert

-

3.

The PCL was resected.

-

4.

The posterior capsule (PostCap) was released with the knee flexed at 90°. The femoral component was removed for an unobstructed view of the posterior capsule, and then a curved osteotome was used to elevate fibres from the distal femoral cortex behind the condyles. Further release of the medial and lateral fibres of the gastrocnemius was performed with a scalpel. The femoral component was then press fit back on for testing.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22, Armonk, NY). To investigate each of the hypotheses set out in the introduction, multiple two-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (RM ANOVAs) were performed to compare knee laxity to the knee state across different flexion angles. When differences were found between successive knee states, post hoc paired t tests with Bonferroni correction were applied at individual flexion angles. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Post hoc power analysis of paired t tests indicated that, when comparing laxities with the standard deviations calculated in eight knees, significant changes of 3.2 mm could be detected with 80% power and 95% confidence.

Separate analyses were performed for anterior laxity with no axial load; anterior laxity with 710 N axial load; posterior laxity with no axial load; and posterior laxity with 710 N axial load.

Results

Anterior translation

With 0 N axial load applied (Table 1; Fig. 2), releasing the PostCap significantly increased laxity by 1.4 mm compared with cutting the PCL at 0° (p = 0.021). However, when a 710 N axial load was applied, no significant difference was found across the different knee states (Fig. 3).

Posterior translation

With 0 N axial load applied (Table 2; Fig. 4), resecting the PCL increased posterior laxity significantly compared to the native knee and CR TKA states at 30°, 60° and 90° (p < 0.05). Releasing the PostCap significantly increased posterior laxity compared to the native knee at all flexion angles, and CR TKA states at 30°, 60° and 90° (p < 0.05). However, no significant increase in laxity was found between the PCL and PostCap steps. When a 710 N axial load was applied, no significant difference was found across the different knee states (Table 2; Fig. 5).

Discussion

The most important finding of the study was that releasing the posterior capsule only caused a small change in AP laxity compared to cutting the PCL when the knee with a CR TKA was non weight-bearing, and did not increase laxity significantly in the loaded knee; therefore, posterior capsular release may not be considered detrimental to overall AP stability if performed during TKA surgery. Given that the posterior cruciate-substituting (PS) TKA is inherently more constrained than the CR TKA, it follows that this finding applies also to PS TKA [8, 13].

The largest effect after posterior capsule release was found at 0° with 1.4 mm increase in anterior laxity with no axial load applied; there was minimal laxity change when 710 N axial body weight was applied. When compared to the 8.5 mm increase in posterior laxity at 90° after cutting the PCL in a deep-dished implant, this laxity change, although statistically significant, is not large in the clinical setting. When comparing stability between the loaded and unloaded experiments, it is clear that stability of TKA is derived by having concave articular surfaces under axial joint compression. For comparison at 0°, the unloaded native knee experienced on average 6 mm anterior drawer and 6 mm posterior drawer, which slightly reduced to 4 and 5 mm, respectively, when loaded. In contrast, the unloaded anterior drawer of the CR state was 11 mm at 0°, which reduced dramatically under applied axial load to 3 mm. The corresponding posterior drawer was 7 mm for unloaded state, reducing to 3 mm when axially loaded.

The role of the posterior aspect of the knee has not been investigated in great detail, and this study is the first to investigate the effect of the posterior capsular release on stability in implanted cadaveric specimens. Morgan et al. investigated the role of different posterior structures and the collateral ligaments in restraining hyperextension in non-implanted cadaveric knees, and found the oblique popliteal ligament to be the primary restraint irrespective of cutting order [18]. With regard to TKA, posterior capsular release has been investigated before in prospective and retrospective clinical trials [12, 17, 23]. Hanratty et al. hypothesised that capsular stripping could improve flexion and range of motion; however, despite finding an immediate increase in knee flexion, no difference was maintained after 3 months or 1 year [12]. Reports of treating flexion contracture post-TKA by posterior capsular release or removal of posterior femoral osteophytes have not considered the possible effect on knee AP stability [14, 21].

A limitation of this study is that cadaveric testing is at time zero. Therefore, healing of the capsule back to the femoral attachment and formation of scar tissue cannot be investigated [12]. However this should not affect the main finding of the study, as healing will only increase stability of the implanted knee post-surgery. Measuring AP laxity with and without a 710 N axial load simulated a comparison between a clinical evaluation of a patient lying supine with relaxed muscles, and a person applying a body weight of 72 kg on the joint; however, this is a simplistic load in direction and magnitude and care should be taken when extrapolating this to kinematics experienced during walking for example.

There is an ongoing debate whether flexion contracture in TKA should be fixed surgically or alternatively treated with continuous physiotherapy postoperatively [14, 22]. This study has found that one such surgical treatment, releasing the posterior capsule from its femoral attachment, did not cause a large detrimental increase in AP laxity at time of surgery. Therefore, posterior capsule release may be considered a safe option to reduce extension deficit. Clinical trials with gait analysis should be performed to highlight how long-term healing may change the effect of posterior capsular release, particularly under full walking loads. Future in vitro studies could quantify how much extension is restored when comparing posterior capsular release to other surgical treatments such as resecting the distal femur, which has a known adverse effect of raising the joint line [20]. The data from the implanted cadavers in this study could also be compared to the constraint of the isolated implants themselves, under the same flexion angles and loading conditions. This would help investigate how much constraint is provided by the different implant geometries compared with the stability provided by the posterior capsule and PCL.

Conclusion

Releasing the posterior capsule only caused a small change in AP laxity when compared with the increase following TKA or PCL resection and, therefore, may not be considered detrimental to overall AP stability if performed during surgery.

References

Amis AA, Scammell BE (1993) Biomechanics of intra-articular and extra-articular reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Jt Surg 75B:812–817

Athwal KK, El Daou H, Inderhaug E, Manning W, Davies AJ, Deehan DJ, Amis AA (2017) An in vitro analysis of medial structures and a medial soft tissue reconstruction in a constrained condylar total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:2646–2655

Athwal KK, El Daou H, Lord B, Davies AJ, Manning W, Rodriguez YBF, Deehan DJ, Amis AA (2017) Lateral soft-tissue structures contribute to cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty stability. J Orthop Res 35:1902–1909

Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H, Victor J, Vanlauwe J (2006) Flexion contracture in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 452:78–82

Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Adams JB (2006) Total knee arthroplasty in patients with greater than 20 degrees flexion contracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 452:83–87

Beynnon BD, Amis AA (1998) In vitro testing protocols for the cruciate ligaments and ligament reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 6:S70–S76

Bull AMJ, Kessler O, Alam M, Amis AA (2008) Changes in knee kinematics reflect the articular geometry after arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466:2491–2499

Fritzsche H, Beyer F, Postler A, Lützner J (2018) Different intraoperative kinematics, stability, and range of motion between cruciate-substituting ultracongruent and posterior-stabilized total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:1465–1470

Gollehon DL, Torzilli PA, Warren RF (1987) The role of the posterolateral and cruciate ligaments in the stability of the human knee—a biomechanical study. J Bone Jt Surg 69A:233–242

Gupte CM, Bull AMJ, Thomas RD, Amis AA (2003) The meniscofemoral ligaments: secondary restraints to the posterior drawer—analysis of anteroposterior and rotary laxity in the intact and posterior-cruciate-deficient knee. J Bone Jt Surg 85B:765–773

Halewood C, Athwal KK, Amis AA (2018) Pre-clinical assessment of total knee replacement anterior–posterior constraint. J Biomech 73:153–160

Hanratty B, Bennett D, Thompson NW, Beverland DE (2011) A randomised controlled trial investigating the effect of posterior capsular stripping on knee flexion and range of motion in patients undergoing primary knee arthroplasty. Knee 18:474–479

Ishii Y, Noguchi H, Sato J, Sakurai T, Toyabe S-i (2017) Anteroposterior translation and range of motion after total knee arthroplasty using posterior cruciate ligament-retaining versus posterior cruciate ligament-substituting prostheses. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:3536–3542

Kim SH, Lim J-W, Jung H-J, Lee H-J (2017) Influence of soft tissue balancing and distal femoral resection on flexion contracture in navigated total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25:3501–3507

LaPrade RF, Morgan PM, Wentorf FA, Johansen S, Engebretsen L (2007) The anatomy of the posterior aspect of the knee—an anatomic study. J Bone Jt Surg 89A:758–764

Mihalko WM, Krackow KA (1999) Posterior cruciate ligament effects on the flexion space in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 360:243–250

Mihalko WM, Whiteside LA (2003) Bone resection and ligament treatment for flexion contracture in knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 406:141–147

Morgan PM, LaPrade RF, Wentorf FA, Cook JW, Bianco A (2010) The role of the oblique popliteal ligament and other structures in preventing knee hyperextension. Am J Sports Med 38:550–557

Okamoto S, Okazaki K, Mitsuyasu H, Matsuda S, Mizu-uchi H, Hamai S, Tashiro Y, Iwamoto Y (2014) Extension gap needs more than 1-mm laxity after implantation to avoid post-operative flexion contracture in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22:3174–3180

Smith CK, Chen JA, Howell SM, Hull ML (2010) An in vivo study of the effect of distal femoral resection on passive knee extension. J Arthroplasty 25:1137–1142

Su EP (2012) Fixed flexion deformity and total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg 94B:112–115

Tanzer M, Miller J (1989) The natural history of flexion contracture in total knee arthroplasty. A prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 248:129–134

Whiteside LA, Mihalko WM (2002) Surgical procedure for flexion contracture and recurvatum in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 404:189–195

Yeh JZY, Chen JY, Lim JW-A, Pang HN, Tay DKJ, Chia S-L, Lo NN, Yeo SJ (2018) Postoperative fixed flexion deformity greater than 10° lead to poorer functional outcome 10 years after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:1723–1727

Zhao D, Banks SA, D’Lima DD, Colwell CW, Fregly BJ (2007) In vivo medial and lateral tibial loads during dynamic and high flexion activities. J Orthop Res 25:593–602

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Smith & Nephew Ltd. Surgical equipment and implants were supplied by Smith & Nephew Ltd. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Spencer Barnes and Mr. Jeff Clark for their assistance with data collection in the laboratory.

Funding

This study, and Dr Athwal’s salary, were funded by research grants to Imperial College London from Smith & Nephew Ltd., who also arranged the specimen-specific cutting guides, loaned the instrument set and donated the prostheses. The Instron testing machine was funded by an equipment grant from Arthritis Research UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KA carried out the experimental study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. PM participated in coordinating the experimental study and data collection. GB carried out the surgical procedures and helped design the study. AA was key contributor to experimental design and interpretation of data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Professor Amis declares that he acts as an expert advisor, holds research grants at Imperial College London, receives royalties from a patent licensed through Imperial Innovations, and has received payment for lecturing from Smith & Nephew Ltd. Dr Athwal declares that his salary is supported by a research grant to Imperial College London from Smith & Nephew Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by REC Wales 12/WA/0196, ICHTB HTA licence 12275, application number R13066-2A. E-mail address tissuebank@imperial.ac.uk.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Athwal, K.K., Milner, P.E., Bellier, G. et al. Posterior capsular release is a biomechanically safe procedure to perform in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27, 1587–1594 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5094-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5094-0