Abstract

Additive manufacturing enables the nearly uncompromised production of optimized topologies. However, due to the overhang limitation, some designs require a large number of supporting structures to enable manufacturing. Because these supports are costly to build and difficult to remove, it is desirable to find alternative designs that do not require support. In this work, a filter is presented that suppresses non-manufacturable regions within the topology optimization loop, resulting in designs that can be manufactured without the need for supports. The filter is based on front propagation, can be evaluated efficiently, and adjoint sensitivities are calculated with almost no additional computational cost. The filter can be applied also to unstructured meshes and the permissible degree of overhang can be freely chosen. The method is demonstrated on several compliance minimization problems in which its computational efficiency and flexibility are shown. The current applications are in 2D, and the proposed method is readily extensible to 3D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Topology optimized designs are often complex, containing many branches or small details. In most cases, the geometrical complexity of these designs cannot be accommodated with conventional manufacturing methods such as milling or casting. Additive manufacturing on the other hand, enables the production of complex parts, by creating a product layer upon layer. Although additive manufacturing offers greater form freedom, it also has manufacturing limitations, such as a minimum feature size, minimum slot distance, and a limitation on the inclination of downward facing surfaces, the overhang limitation (Thomas 2009). The present study concentrates on the overhang limitation.

Most additive manufacturing processes, such as selective laser melting (SLM), fused deposition melting and stereo lithography, exhibit an overhang limitation. This is caused by the fact that each layer needs a certain amount of mechanical support or thermal conduction from the previously built layer, which limits the distance that a layer can extend unsupported over the layer underneath. Manufacturability is thus controlled by the angle between a down-facing surface and the base plate, the overhang angle, as defined in Fig. 1a. The minimum overhang angle, αoh, is the smallest manufacturable overhang angle. For SLM, this angle is mostly reported around 45∘ (Thomas 2009), but varies for different process conditions (Wang et al. 2013; Cloots et al. 2013). Overhanging regions of a design with α < αoh can be built by adding support structures as displayed in Fig. 1b. However, support structures increase the build time, add material cost, and their removal can be a difficult and costly task, especially for internal structures that are difficult to access.

Consequently, developing topology optimization methods that incorporate a minimum overhang angle became an active research topic. To the best of authors’ knowledge, Brackett et al. (2011) were the first to investigate manufacturing constraints for additive manufacturing in a topology optimization context. They proposed a methodology to measure the overhang angle for evolutionary topology optimization, but this method has not been implemented. The first actual implementation was done by Gaynor et al. (2014), detailed in Gaynor and Guest (2016). A wedge shaped filter in combination with Heaviside projection was used to obtain self-supporting topologies. However, due to the non-linearity introduced by the overhang filter in combination with Heaviside projection, the number of iterations required for convergence was high. Subsequently, Langelaar (2017) presented an overhang restriction that evaluates the overhang angle on a structured mesh, where the amount of material below each element is used as a measure for overhang. Self-supporting designs were obtained in 2D as well as in 3D (Langelaar 2016). However, the filter is only applicable to rectangular structured meshes, and αoh can only be tuned by changing the element aspect ratio.

Both (Gaynor and Guest 2016) and (Langelaar 2016, 2017) evaluate the manufacturability in a global sense, following the layer by layer fashion of the manufacturing process. Other methods, that only constrain the overhang angle locally, have also been presented. Both (Qian 2017) and (Allaire et al. 2017a) proposed a geometrical overhang constraint by constraining the angle between the normal vector at the perimeter and the build direction. Qian (2017) uses density-based topology optimization in combination with a non-discreteness constraint to suppress intermediate densities, while in Allaire et al. (2017a) level-set-based topology optimization is used. Although both methods reduce the overhang, unmanufacturable sawtooth patterns are generated, due to the local nature of the methods. Finally, Guo et al. (2017) introduced an overhang constraint for moving morphable components and moving morphable voids. Although a large number of iterations is required, the resulting designs are overhang free. Unmanufacturable sawtooth patterns are avoided by preventing voids to overlap. Furthermore, the importance of build orientation is shown by including orientation in the optimization.

Besides the direct implementation of a minimum overhang angle as a design rule, other approaches have been proposed to limit the amount of support material required for manufacturing. Mirzendehdel and Suresh (2016) presented a constraint on the support structure volume. However, when no support was allowed, the discontinuous identification of overhanging surfaces seemed to result in a casting constraint, eliminating also the allowable overhanging surfaces. Although feasible, the results will most likely be sub-optimal. Finally, Allaire et al. (2017a, b) presented a constraint on the compliance of the intermediate shapes of a topology during the layer-by-layer manufacturing, which should constrain the overhang naturally. This is reflected in the results, where the amount of overhang is reduced. Although physics-based constraints have great potential by, e.g., predicting distortions during and after manufacturing, they tend to be computationally expensive, as the compliance of partly build designs has to be evaluated or approximated many times per iteration.

In order for a method to be of practical use in an industrial setting, it should meet the following requirements. First of all, the critical overhang angle should be adjustable, since this value varies according to the specific process conditions and the choice of material. Second, the overhang restriction should be able to work on unstructured meshes. In practical situations, the design domain is rarely rectangular and can contain holes and curved surfaces, which cannot be discritized with a structured mesh. Furthermore, the overhang restriction should be computationally inexpensive; its evaluation time and sensitivity analysis time should be of the same order, or lower, as the objective evaluation time, and should not add an excessive amount of iterations required to converge to the optimum layout. Finally, the overhang restriction should not contain parameters that need to be tuned for every optimization problem.

This article presents a method to control the angle of overhanging regions during topology optimization which addresses all the above mentioned requirements. Overhanging regions are identified by mimicking the layer upon layer manufacturing process. Instead of adding discrete layers, the printing history is modeled as a continuous process with an advancing front. By employing efficient algorithms developed to solve front propagation problems in combination with adjoint sensitivities, the additional computation cost remains small. This method of overhang detection was first presented in van de Ven et al. (2018), where the overhang limitation was included as an additional constraint. In this paper, it is enforced through a filter, improving the robustness of the method. The formulation of the filter based on front propagation is dimension and mesh independent (Sethian 1996), which allows for extension to 3D. For the sake of brevity and clarity of the discussion, the overhang restriction method and examples will be presented in a 2D setting only.

The next section introduces the overhang detection procedure, and the implementation thereof in topology optimization is discussed in Section 3. The numerical implementation is shown in Section 4, and numerical examples are presented in Section 5. Finally, conclusions are given in Section 6.

2 Overhang detection

In this section, the overhang detection procedure based on front propagation, as presented in van de Ven et al. (2018), is presented. The resulting procedure is subsequently used in the topology optimization to eliminate overhanging regions.

2.1 Overhang detection through front propagation

Front propagation methods track an initial curve or surface Ω0 as it evolves in space. This has a clear resemblance with the additive manufacturing process, where with every added layer, the boundary of the product advances. Instead of tracking the propagating front explicitly, the arrival time field of the propagation is calculated. The arrival time of a spatial point represents the time at which the front reaches that location. The front propagation can then be reconstructed by observing isolines of the arrival time field. How the front propagates, is ultimately determined by a speed function, which dictates the propagation of the front in each direction and location.

Consider the geometry given in Fig. 2, that is to be printed on the base plate Ω0, which coincides with the initial position of the front. When printed in the b-direction with αoh = 45∘, the shaded region will be overhanging, meaning that it will fail during printing. Although the complete extended region on the top-right is overhanging, from here on we will reserve the term overhang for regions that are not manufacturable due to the overhang limitation. The goal of the front propagation is to detect this region in a cost effective, robust, manner. When the front, initially at Ω0, is propagated with an isotropic speed function within this geometry, it starts to curve around corners, as can be seen in Fig. 3a. In order to obtain an arrival time field that represents the printing sequence of individual layers, the speed function is modified such that the front travels faster in directions deviating from the build direction. This increase in speed compensates for the larger distance to be traveled in the hanging region, so that the front stays parallel to base plate Ω0 instead of curving, as illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Contour plots of the arrival time fields for a an isotropic speed function, b an anisotropic speed function that gives equal arrival times per layer, and c an anisotropic speed function that delays the propagation in overhanging regions, and d for the delay field τ, from which the overhanging region can be identified

Finally, in order to detect overhang, the propagation speed is decreased when the front travels in a direction below αoh, as shown in Fig. 3c. The earliest possible arrival time, i.e. the minimum arrival time, for a point is the arrival time of a front that has traveled straight from the base plate toward that point, which is equal to the distance toward the base plate divided by the propagation speed:

where b is a unit vector parallel to the build direction, f(b) is the propagation speed in that direction, and a ⋅b denotes the inner product between vectors a and b. In all non-overhanging regions, the arrival times are equal to the minimum arrival times, while in overhanging regions the arrival times exceed the minimum arrival time. Therefore, overhang is detected by observing the delay

where T(x) is the arrival time obtained through front propagation. When the delay τ = 0, there is no overhang, and when τ > 0 there is overhang (Fig. 3d). This procedure can be used on arbitrary geometries to detect overhanging regions as will be demonstrated in Section 5. In the following section the speed function required for the overhang detection will be proposed. This speed function is then used in the governing equations to obtain the arrival time field, as discussed thereafter in Section 2.3.

2.2 Anisotropic front propagation

As discussed in the previous section, the propagation speed is decreased when the front travels in directions below αoh. This is done by making the speed function direction dependent. Consider a point x, whose arrival time is to be calculated, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The arrival time is updated from a given point x′ on the front, where the arrival times are known. Finding x′, from where x is to be updated, is covered in Section 2.3. The new arrival time can be calculated with

where a = (x −x′)/(∥x −x′∥) is a unit vector pointing from x′ to x, and f(a) is the speed function, dependent on the direction of the update. ∥...∥ is used throughout the paper to denote the L2 norm. The update direction is defined as α = π/2 − arccos(a ⋅b). Let us first consider a speed function that results in equal arrival times per layer as in Fig. 3b. The time difference between two points should match the distance between the points projected on the build direction, divided by the propagation speed in the build direction f0:

f0 is a constant that simply scales the arrival time field and is set to 1m/s. By combining (3) and (4), the speed function becomes:

In order to obtain an arrival time field as shown in Fig. 3c, the propagation is delayed in overhanging regions. This is achieved by decreasing the speed function whenever the update direction a is below the critical overhang angle, i.e. when α < αoh or α > π − αoh, or equivalently a ⋅b < sin(αoh). The speed can be decreased in numerous ways, and for numerical reasons detailed in Section 4, the speed function for propagation in directions below αoh is chosen as:

where P = (I −b ⊗b), and a ⊗b denotes the outer product between the vectors a and b. It can be shown that f2 < f1 when a ⋅b < sin(αoh) and f1 = f2 when a ⋅b = sin(αoh), hence decreasing the speed for propagation below αoh.

So far, only upwards updates, where a ⋅b ≥ 0, have been considered. The speed function should also be defined when the direction of propagation is downwards, i.e. when a ⋅b < 0. Downward propagation might happen in hanging regions, which by definition are overhanging, as can be seen in Fig. 5. The downward propagation speed can in principal be chosen freely as long as it is greater than zero, since there will always be a delay because the front has to cover additional distance to reach hanging areas from within the structure. For numerical convenience, the downward profile is chosen identical to the upward propagation profile. The speed function is then

This can be rewritten as

This gives a speed function with a rectangular shape when displayed in polar coordinates, as can be seen in Fig. 6, suitable for overhang detection. The effect of the minimum overhang angle on the speed function is displayed in Fig. 7: lower minimum overhang angles widen the speed function, increasing the anisotropy.

2.3 Governing equations

Using (3) and (8), the arrival time at a point x can be calculated given a point x′ with a known arrival time. In order to obtain the arrival time field, each point should be updated from the direction that results in the earliest arrival time (i.e., the direction from which the front reaches the point first). Therefore, (3) is minimized for all directions a ∈ S1, S1 = {a ∈Rn | ∥a∥ = 1}, where n is the dimensionality of the problem. By doing so and linearizing around x, the front propagation problem can be described as a boundary value problem governed by the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation, which is solved for T:

where Ω is the interior of the domain and ∂Ω0 is the (partial) boundary of the domain at which the front is initiated. At the initial boundary, the arrival times are set to zero, and from there, arrival times can be progressively calculated throughout the domain, by which the front is advanced. Effectively, the front is advanced by calculating for every location the fastest path to the known front.

Instead of calculating the fastest path toward the front, another perspective is to expand the front and calculate the time it takes to reach each location. The front is expanded by the speed function F(x,n), dependent on the normal direction of the front, which is determined by the gradient of the arrival times: n = ∇T/∥∇T∥. The norm of the gradient ∇T determines how fast the arrival time changes spatially, and has to be equal to the reciprocal of the speed function. This gives the governing equation

Note that the speed function F is generally not equal to the speed function f. For a detailed relation the reader is referred to Vladimirsky (2001), but F can interpreted as the speed of the front in the normal direction (semi-Lagrangian perspective) while f is the speed for an individual particle (Eulerian perspective), which do not coincide when the speed function is anisotropic.

Solving either (9) or (10) yields the same result, but for (10) a root finding problem needs to be solved locally, while for (9) this is a minimization problem. One or the other might be easier to solve depending on the speed functions f and F. For the speed function given in (8), the local minimization problem can be solved efficiently as will be shown in Section 4. Therefore, this study will focus on solving the front propagation with the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation.

2.4 Interpretation of the delay field

With the speed function given in (8), the resulting delay field has a physical interpretation. The delay at a point x is proportional to the distance to the closest non-overhanging, or manufacturable, point in the layer in which x is printed, i.e. in the direction orthogonal to b. f∗ is a speed that relates the delay to this distance:

where doh is the distance from x to the closest manufacturable point in the same layer. For manufacturable points, the distance to the closest manufacturable point, i.e. to itself, doh = 0, and the delay of manufacturable points is zero.

Now consider a point x that is updated from a manufacturable point x′, as depicted in Fig. 8. The delay τ(x) is calculated with (1)–(3), and should be proportional to doh:

Assuming that x′ is manufacturable gives T(x′) = Tmin(x′) = x′⋅b/f0(1). Furthermore, Tmin(x) = x ⋅b/f0. Simple trigonometry gives

Then, by combining (12) and (13) the following expression for the speed function is obtained:

By choosing f∗ = tan(αoh)/f0, this reduces to

which is equal to the speed function for overhanging regions (6). The delay of a point x is thus proportional to the distance of x to the closest manufacturable point in the layer in which x is printed.

3 Integration in topology optimization

With the overhang detection procedure outlined in the previous section, an overhang filter for topology optimization is formulated. In van de Ven et al. (2018), this overhang detection procedure was used in an explicit overhang constraint. However, this required the introduction of several additional parameters and constraint aggregation, resulting in some constraint violations. Therefore in this work, αoh will be enforced implicitly through a filter, as has been done for the overhang constraints in Gaynor and Guest (2016) and Langelaar (2017). The filter will be integrated in a density based topology optimization (Bendsoe and Sigmund 2003). A schematic of the optimization flowchart is given in Fig. 9a. First, the design variables ρ are filtered (Bruns and Tortorelli 2001) to control length scale and to prevent checkerboarding (Sigmund and Petersson 1998):

where \(\rho ^{*}_j\) is the filtered density at position x j and r is the filter radius. The filtered densities ρ∗ define the geometry on which the overhang is detected with front propagation. This results in the printable densities ξ, which are used for the objective and constraint evaluation. Finally, the sensitivities are calculated and the design variables updated.

3.1 The overhang filter

The overhang filter, as indicated in Fig. 9b, comprises of three steps. First, the filtered densities ρ∗ are pre-processed. Then, the front propagation is performed which gives the arrival time field T. Lastly, the arrival times are post-processed to obtain the printable densities ξ (Fig. 9b). These three steps are discussed in detail in the following sections.

3.1.1 Pre-processing and front propagation

In density based topology optimization, the topology is defined by a pseudo-density field that determines the amount of material at every location. In order to capture this topology in the front propagation, the propagation speed is scaled by the local filtered density ρ∗. Furthermore, a lower bound for the scaling, vvoid, is introduced to prevent infinite arrival times in void regions. For simplicity, a linear interpolation is used, which gives the speed scaling field

where typically vvoid = 0.1 is used. The speed function (8) is, again for simplicity, linearly scaled by this field giving

The front propagation is performed with this scaled speed function.

3.1.2 Post-processing

After the front propagation is conducted, the delay field (2) can be constructed, given by

The delay is zero for manufacturable regions and larger than zero for overhanging regions. In order to compare printable densities with the original densities, a dimensionless field is required that is 1 for manufacturable regions and between 0 and 1 for overhanging regions. Therefore, the following function is used to map the arrival time delay to printability:

where k[s− 1] controls how rapidly printability decreases with an increasing delay. It is defined as follows:

Because of the negative power of 2 in (22), β[m] can be interpreted as the typical length after which the printable density of an overhanging part is halved. The relation between ξ and τ for different values of k is displayed in Fig. 10. By increasing k, sharper edges and finer details are obtained, lower values of k can result in smoother convergence. β is typically chosen as h/4, where h is the typical element length.

3.1.3 Initial condition for the front propagation

The arrival times are initialized at the base plate for the preferred building direction. Although the boundary on the base plate is manufacturable, as it is completely supported by the base plate, the arrival times are not initialized at 0, but with a slight offset T0 proportional to the density:

Without this offset, the delay τ on the bottom layer will be 0, regardless of the density value. The printable densities ξ on the base plate will then be 1(22), resulting in a permanent layer of material on the base plate. With this offset, the initial arrival times are dependent on the local densities, and when the densities are 0, the delay τ = T0. T0 is chosen such that a sufficiently small printable density is obtained when the local density is zero. For example, T0 = 8/k, results in an acceptable ξ = 0.0039 when ρ∗ = 0(22).

4 Numerical implementation

Efficient evaluation of the front propagation problem and its sensitivities is of paramount importance for its feasibility as an overhang filter. Fortunately, the directionality of the front propagation problem allows for a fast calculation of the arrival time field: because the arrival time at one location can only influence locations with a higher arrival time, the arrival times can be calculated using single-pass methods. These methods start at the boundary, and propagate the front by calculating arrival times in ascending order from the boundary. In principal, the arrival time at every location only needs to be evaluated once, hence the name single-pass. For the evaluation of an arrival time only a local problem is solved, resulting in a close to linear scaling of the algorithm with a computational complexity of O(N log N). For isotropic speed functions, the Fast Marching Method has been developed (Sethian 1996), which is commonly used in, among others, the level-set method (Sethian and Wiegmann 2000), but also in other optimization settings (e.g. van Keulen et al. 2008). The Fast Marching Method has been expanded into the Ordered Upwind Method (OUM) (Sethian and Vladimirsky 2003) for anisotropic speed functions. Furthermore, iterative methods have been developed, called fast-sweeping methods, and mixtures of marching and sweeping methods. Additionally, parallelized methods are available. However, since the performance of the OUM is sufficient and its implementation is straightforward, no alternatives have been considered.

4.1 Ordered upwind method

For the sake of completeness, the OUM will be briefly explained, following Sethian and Vladimirsky (2003). From here on we consider a 2D setting with triangular elements. Consider a discretized domain with N nodes. Node i is located at x i , and field quantities at node i are denoted with a subscript, e.g. ρ i . In the OUM, each node is labeled as being either Far, Considered or Accepted. Initially, all the nodes are labeled Far, except for the initial boundary nodes which are labeled Accepted. Each iteration can be divided into three steps:

-

1.

Move all the nodes that are in Far and adjacent to an Accepted node to Considered.

-

2.

Evaluate the arrival times of the nodes in Considered, using the Accepted nodes.

-

3.

Move the node in Considered with the earliest arrival time to Accepted.

This process is repeated until all the nodes are in Accepted. In Step 2, the arrival times of Considered nodes are calculated using the current front. The current front is defined in 2D as the set of line segments x j x k , for which x j and x k are adjacent to each other, in Accepted, but also adjacent to one or more Considered nodes. Nodes that fulfill these three requirements are said to be in the AcceptedFront (AF). In order to calculate the arrival time of a Considered node x i , the current front is scanned to see for which location on the front the travel time to the node in question is the shortest, as displayed in Fig. 11. Only a small part of the current front, which is close enough to x i to possibly provide the earliest arrival time, needs to be considered. This is the so-called near front (NF) of x i :

where h is the typical mesh diameter, and G1 and G2 are the lower and upper bound of the speed function f s , respectively. G2/G1 is a measure for the anisotropy of the speed function. The arrival time at x i is updated from the segment of NF(x i ) that gives the lowest arrival time:

where \(V_{\mathbf {x}_j \mathbf {x}_k}(\mathbf {x}_i)\) is the upwind approximation of T i when calculated from line segment x j x k . \(V_{\mathbf {x}_j \mathbf {x}_k}(\mathbf {x}_i)\) can be evaluated from either the semi-Lagrangian (9) or the Eulerian (10) perspective. As stated in Section 2.3, the semi-Lagrangian perspective is used in this work, but similar results can be achieved using the Eulerian perspective. Following Sethian and Vladimirsky (2003), \(V_{\mathbf {x}_j \mathbf {x}_k}(\mathbf {x}_i)\) is approximated with:

where χ(ζ) = ∥x i −c ζ ∥, and a ζ = (x i −c ζ ) /χ(ζ). c ζ = ζx j + (1 − ζ)x k , which is a point on the segment x j x k determined by ζ. For example, in order to calculate T i for a Considered point x i , as displayed in Fig. 11, the lowest possible arrival time for each segment on the AF is determined by solving (27). Then, the update that gives the earliest arrival time is accepted (26). Due to the anisotropy of the speed function, this is often not the closest point and the update might even cross several elements (as is, for example, the case for the update from c2 and c3 in Fig. 11). Nonetheless, the speed function f s is assumed to be constant, as its only spatially varying argument, the speed scaling field ϕ, is only evaluated at the target location x i (27). No instabilities have been observed related to this approximation, but one could make a more precise approximation by interpolating ϕ over the update path. However, (27) will become more difficult to solve, and the sensitivities will be less local as the arrival time will then depend on the densities of all the nodes from the elements that are crossed.

Although (27) is evaluated for every segment in the near front, the eventual arrival time T i will only depend on the earliest upwind approximation \(V_{\mathbf {x}_j,\mathbf {x}_k} (\mathbf {x}_i)\). Therefore, T i is only a function of the arrival times that appear in \(V_{\mathbf {x}_j,\mathbf {x}_k} (\mathbf {x}_i)\), and the speed scaling field at x i , ϕ i . For brevity, (26) is written as

The minimization problem given in (27) needs to be solved multiple times for every node that is updated. Therefore, solving it efficiently is crucial for a computationally fast overhang filter. The second and third term of (27) are linear with ζ. With the speed function given in (20), the first term of (27) can be rewritten as

with only c ζ linearly dependent on ζ. In two dimensions, the arguments of the maximum function are piecewise linear functions of ζ. The other terms in (27) are also linear functions of ζ. Consequently, (27) is piecewise linear in ζ, and the minimum will be either at the edges of the domain (ζ = 0 or ζ = 1), or at the intersection points of two piecewise linear sections. This will only occur when the two arguments of the maximum function are equal:

In two dimensions, this gives two possible intersection points:

Therefore, the minimum in (27) is efficiently obtained by simply evaluating the minimization problem at ζ = (0,1,ζ1,ζ2), and accepting the minimum value that lies on the interval (i.e. 0 ≤ ζ ≤ 1).

Summarizing, in each iteration of the algorithm, the node with the lowest arrival time is added to the set of Accepted nodes, and its neighboring nodes’ arrival times are updated. The arrival time of a node is updated by scanning the front within a certain radius of that node for the shortest arrival time (26). The minimum arrival time on a segment is found by solving (27), which can be done by probing the line segment at four locations. In 3D, the front is represented by a surface, and the arrival time of a node is updated from a surface instead of a line. The minimization problem presented in (26) is therefore more complex, and will be elaborated in a separate paper.

4.2 Sensitivities

The sensitivities are derived from the descritized equations as outlined in (25)–(32). By doing so, the computational effort for the sensitivities becomes negligible; only one loop over all the nodes is required as will become clear in Section 4.3. The sensitivities are given for a general function g which is a function of the printable densities ξ. This could be either the objective or a constraint function. The sensitivities with respect to the arrival times follow directly from the chain rule:

In order to obtain the derivatives of the arrival times T with respect to the velocity field ϕ, the state (28) is added to g for every node, multiplied by an adjoint field λ:

Deriving with respect to the velocity field gives

The summation can be combined and the term dV j /dϕ i expanded:

Since the last term consists of two nested summations, both from 1 to N, the indices k and j can be swapped:

Now all the terms containing dT j /dϕ i can be combined:

By choosing the adjoint such that the terms between brackets becomes zero, dT j /dϕ i does not need to be evaluated. Therefore, the following condition has to be satisfied:

Finally, the sensitivities become

However, ∂V j /∂ϕ i is only nonzero when j = i, which simplifies the sensitivities to

The sensitivities with respect to the densities follow from the chain rule:

where, from (19), \(\partial \phi _j / \partial \rho _j^{*} = (1-v_{\text {void}})\), and \(\mathrm d \rho _j^{*} / \mathrm d \rho _i\) is the derivative of the density filter. Note that for the nodes on ∂Ω0, the derivatives are slightly different due to the initialization (24):

4.3 Evaluating the adjoint

Equation (40) can be rearranged to obtain a recursive expression for the adjoint variables:

The second term on the right-hand side can be evaluated directly with (34). For the first term on the right-hand side, the adjoint variables λ k of the nodes k whose arrival time has a dependence on the node j in consideration, i.e. when ∂V k /∂T j ≠ 0, must be known. By evaluating the adjoint in the opposite order as in which the arrival times have been calculated during the front propagation, it is guaranteed that the adjoint variables are evaluated before they appear in the first right-hand side term for another adjoint variable: clearly, ∂V k /∂T j ≠ 0 only when T k is based on, and thus calculated after, T j (note that the partial derivative ∂V k /∂T k = 0). However, a variable number of arrival times T k can depend on arrival time T j . Therefore it is more convenient to index on which arrival times T j depends, since every arrival time depends on exactly two other arrival times (28), except for the nodes on ∂Ω0, whose arrival times depend only on the local density (24).

Thus, during the front propagation, the order in which arrival times are accepted is stored in an array o, and the indices of the two nodes on which the accepted arrival times depend are registered in arrays c1 and c2. The adjoint variable can then be evaluated in a single loop, as outlined in Algorithm 1. Note that ∂V/∂T is a sparse matrix with two entries per row and ∂V/∂ϕ has only entries on its diagonal.

5 Results

In this section, the newly developed overhang filter is demonstrated on a given geometry, and on three cases where the compliance is minimized. The optimization problem reads as follows:

Here f and u denote the load and displacement vector, respectively. K(ξ) is the element stiffness matrix evaluated on the printable density field ξ. V (ξ) is the total volume, also evaluated on the printable densities, and \(V_{\lim }\) denotes the maximum permitted volume. The sensitivities of the objective and constraint w.r.t. the printable densities can be found in e.g. Bendsoe and Sigmund (2003).

The first test case that is presented is the cantilever problem, which is well known and therefore allows for a clear interpretation of the results. The second case is a tensile test case, which has a sharp contrast between the objective and obtaining an overhang-free design. Finally, the capability to detect overhang on an unstructured mesh is demonstrated on the optimization of a crane hook. On the test cases, the filter is tested for several overhang angles, filter sizes and volume fractions. Finally, the computational cost is evaluated.

Unless stated otherwise, the following parameters are used in the upcoming examples. The Young’s modulus E is set to 1 and 1 ⋅ 10− 6 Nm− 2 for material and void, respectively, and the Poisson ratio ν = 0.3. The applied force F = 1N. RAMP penalization is used with q = 10 (Stolpe and Svanberg 2001). The optimizations are run for 100 iterations with the Method of Moving Asymptotes (MMA) optimizer (Svanberg 1987), in order to test different cases with roughly the same computational time, as this is often limiting factor in a practical environment. Standard increase and decrease parameters of respectively 1.2 and 0.7 are used. The Portable and Extendable Toolkit for Scientific Computing (PETSc) (Balay et al. 1997, 2016) is used to parallelize the FEM assembly and solve (not the front propagation), in combination with the Multifrontal Massively Parallel sparse direct Solver MUMPS (Amestoy et al. 2001, 2006). All the presented examples can be run on a single desktop, therefore, the implementation of PETSc is mainly intended for future 3D cases.

5.1 Overhang detection

Consider a typical material distribution one might encounter during a topology optimization on an unstructured mesh, as given in Fig. 12a. The overhang filter is applied as follows. First, front propagation with αoh = 40∘ is performed on the given geometry, resulting in the arrival time field as shown in Fig. 12b. Due to the numerical implementation of the front propagation, there is slight rounding of the corners of the arrival time field iso-contour lines. The rounding causes a small overestimation of the critical overhang angle, and can be reduced with mesh refinement. However, this is generally not necessary as the error is small, for this particular case in the order of 2∘. From the arrival time field the delay field is calculated, as shown in Fig. 12c. In this field the non-overhanging area with τ = 0 (no delay) is already clearly visible. The printable densities are then evaluated with (22), resulting in the material distribution given in Fig. 12d. Compared to the original density field, the overhanging regions are removed, and the top-right member that is close to printable has intermediate densities. During the optimization, penalization of intermediate densities will limit the emergence of intermediate density values in the optimized topologies.

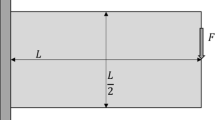

5.2 Cantilever test case

The overhang filter is first applied to the cantilever case, where compliance is minimized on a rectangular domain, as illustrated in Fig. 13. The domain length a = 1.0m, and the domain is fully clamped on the left side and a vertical point force acts on the right side. The domain is discretized with a structured triangular mesh, comprised of 30 000 elements, with an average element edge length of 4.6mm. Furthermore, a density filter is applied with a filter radius of 20mm, and the volume is constrained at 50% of the design domain. The optimal design without overhang filter is depicted in Fig. 14a. Its final objective, Cref = 70.087J, is used as a reference for the overhang-free designs. Although this design is printable when rotated 90∘ counter-clockwise, the overhang filter is applied to make the designs printable when the build direction coincides with the y-axis, with αoh = 45∘. The overhang filter parameters are chosen as k = 500, T0 = 0.02 and vvoid = 0.1. With overhang filter, a discrete, overhang-free design is obtained, as can be seen in Fig. 14b. The initially overhanging members are supported, and most down-facing edges make a 45∘ angle with the base plate, lying exactly on the limit. The objective of the printable design is 12% higher than the conventional design, due to the added manufacturability filter. It can be observed that the edges of the filtered design are crisper than in the original design, which is controlled by the value of k. Lower values of k will decrease the crispness.

Compared to the constraint implementation presented in van de Ven et al. (2018), the cusps at the topside of the small holes depicted in Fig. 14b are crisper, with almost no overhang present when the filter approach is implemented. With the constraint implementation, overhang was not completely eliminated in small holes (van de Ven et al. 2018). The cost per iteration of both methods is roughly equal, since front propagation and the corresponding sensitivity calculation are identical in both approaches.

5.3 Initial configuration, convergence and continuation

The optimization with overhang filter converges smoothly, and after 50 iterations the design hardly changes, as can be seen in Fig. 15. The objective is autonomously low at the start as an initial density field of ρ = 1 is imposed, implying a completely filled domain and resulting in a violation of the volume constraint. After 10 iterations, when the volume constraint is satisfied, the objective decreases monotonically. The choice of a completely filled initial configuration is necessary to allow the optimizer to place material freely throughout the complete domain in the first few iterations. If the optimization starts with a density distribution in accordance with the volume constraint, i.e. ρ = 0.5, most of the domain is detected as overhanging and therefore does not contribute to the overall stiffness. Consequently, the design grows from the base-plate in the build direction, with slower convergence behavior and results in a far-from-optimal local minimum, as can be seen in Fig. 16.

Convergence behavior for the cantilever case with and without continuation. The snapshots are taken at iteration 10, 25, 50 and 100, from the optimization without continuation. Note that without continuation, the optimization starts from a completely filled design, hence the high performance in the first few iterations when the volume constraint is not yet satisfied

However, also with the completely filled initial configuration, like every nonconvex topology optimization problem, the optimization with overhang filter is susceptible to converge to inferior local optima. As can be seen in Fig. 14b, not all the material contributes to the stiffness of the structure: the supporting leg on the bottom right has no mechanical function as the bottom of the domain is mechanically unconstrained. Although it is expected that enforcing printability decreases the overall performance, it seems that this member could have been placed under a 45∘ angle to add support as well as stiffness, instead of only support. From the optimization history it becomes clear that this member is formed early in the optimization to allow material around the point where the force acts, and is not repositioned later on.

A common method to avoid inferior local optima is to apply continuation. In order to activate the overhang constraint in a gradual manner, the physical densities ξ c are linearly interpolated between the filtered densities ρ∗ and the printable densities ξ:

where the objective and constraint evaluations are now performed on the physical densities ξ c , and η ∈ [0,1] is the continuation parameter. In the remaining examples in this paper, when continuation is applied, η is continuously increased from 0 to 1 over the first 25 iterations of the optimization.

The resulting design with continuation is displayed in Fig. 14c, and its convergence behavior is plotted in Fig. 15. When continuation is used, the initial configuration can be chosen as a uniform density distribution of ρ = 0.5, resulting in a higher initial objective as compared to the optimization without continuation but satisfying the volume constraint. In the first 25 iterations the objective decreases, but not monotonically due to the ramp up of the continuation parameter η. Generally, when continuation is used an improvement is observed in the final objective, as compared to the value of the final objective attained without continuation.

5.4 Variable overhang angle

The novel overhang detection method based on front propagation can filter out overhangs with any value of αoh. However, for very large angles (αoh > 60∘), the optimization does not converge well as it becomes harder to find topologies that meet such a stringent manufacturing constraint. Since such high overhang angles are usually printable with modern printers, a parameter study for 10∘≤ αoh ≤ 60∘ is performed. For every angle three calculations are performed: without continuation, with continuation as described in Section 5.3, and with extra long continuation where η is continuously increased from 0 to 1 over the course of 100 iterations and the optimization is run for 400 iterations. The results are shown in Fig. 17, and the final objective values are plotted in Fig. 18.

The final objective and volume constraint values as a function of the minimum overhang angle. The objective increases with the overhang angle, as more material has to be used for supporting purposes. Furthermore, it can be seen that continuation does not always lead to a lower objective. The volume constraint is overall satisfied

As expected, lower overhang angles result in designs similar to designs obtained without activating the overhang filter as shown in Fig. 14a. For higher overhang angles, more material is required for support, and the objective increases. Furthermore, as observed in the previous sections, the optimizations without continuation contain a higher fraction of material that does not contribute to the stiffness, but is only in place to satisfy the overhang limitation. Except for αoh = 60∘, the extra long continuation does not seems to contribute to better designs. This can also be seen in the final objective values, which are plotted in Fig. 18. Interestingly, although the designs with continuation look visually more appealing than the designs without continuation, their overall objective values are only slightly lower for several overhang angles.

5.5 Filter size

The final parameter to be investigated on the cantilever case, is the density filter radius. For this parametric study, the optimizations are performed on a finer mesh comprised of 180 000 elements, in order to accommodate smaller radii. The average edge length is 1.9mm, and the filter is varied from 3mm to 40mm. The resulting designs are displayed in Fig. 19. It is clear that the filter radius has an effect on the feature size, as smaller features appear for smaller radii. For these smaller radii, supporting structures hardly cost any volume. Therefore, the main structure can resemble the original design closely, resulting in a lower objective value, as can be seen in Fig. 20, where the final objective values are plotted. Although oscillatory boundaries develop under the main structural beams for small density filter radii, the presence of these detailed features is not a manifestation of the sawtooth patterns observed when the overhang is only locally evaluated (Allaire et al. 2017a; Qian 2017): in our results the cusps of any sawtooth are at all times sufficiently supported, and thus manufacturable.

Exact control over the length scale is lost, since members can be positioned such that they are partially overhanging, resulting in thinner members in the overhang filtered design. In order to impose an exact minimum feature size, one should apply an additional filter after the overhang filter. Because a linear weighted average filter would reintroduce overhang in sharp corners, a dilate filter could be used Sigmund (2007).

5.6 Tensile test case

An extreme test for the overhang filter is the tensile test case. The case is similar to the cantilever case except that the force acts in the horizontal direction and is applied closer to the top side, as displayed in Fig. 21. Without overhang filter, the optimal design is a beam connecting the force to the fixed side. For the purpose of testing our algorithm, we disregard the possibility to translate the beam to the base plate. The bottom side of this beam will be completely overhanging, and therefore supports need to be generated to connect the base plate to the beam. These supports will have no mechanical function, and thus completely counteract the objective with volume constraint. Therefore, it is a good test to see if the overhang filter is able to generate fully dense supports, that have no function other than supporting the design.

The tensile test case is optimized for several volume fractions, ranging from 10% to 50%, and for a 20mm and a 7.5mm filter radius, as displayed in Fig. 22, without the use of continuation. It can be seen that for volume fractions of 30% and higher, fully dense supports are created for both filter sizes. With decreasing volume fraction, the material available to increase the stiffness diminishes. Consequently, for 20%, the larger filter size is unable to converge to a black and white design, and for 10%, neither converges to a black and white design.

Results for the tensile test case for various volume fractions and for a a 20mm filter radius, and b a 7.5mm filter radius. For small volume fractions, dependent on the filter radius, not enough material is available to support the design, and the optimizations fail to converge to a black and white design

Furthermore, it can be seen that there are some supports that “zigzag” downwards, instead of a more volume efficient straight line. This behavior can also be seen in Fig. 19, for r = 3mm. However, the influence on the objective is usually minute, as this is mostly observed for thinner supports.

5.7 Crane hook case

For the final case, the compliance of a crane hook is minimized in order to demonstrate the overhang filter on a domain that is not easily meshed with a structured mesh, as is often the case in industrial practice. The domain and boundary conditions are displayed in Fig. 23. The domain is mechanically clamped at the top and a vertical distributed load of 1N/m is applied on the inside of the hook. The compliance is minimized subject to a 40% volume constraint. The domain is meshed with 4000 elements with an average edge length of 46mm, and a density filter with a 75mm radius is applied and continuation on the overhang filter is used. Without overhang filter, the resulting design resembles a typical hook, as displayed in Fig. 24. When the overhang filter with αoh = 45∘ is applied, the design changes as can be seen in Fig. 25a. A clear, overhang free, design is obtained. Due to the relatively coarse mesh, the final design contains some rough edges. With mesh refinement, this disappears as can be seen in Fig. 25b, where the domain is meshed with 16 000 elements.

Overhang free designs for the crane hook case on a the mesh as displayed in Fig. 23, and b a 4x finer mesh

5.8 Computational efficiency

Since the computational complexity of the OUM used by the overhang filter is of O(N log N) worst case, it is expected that the computational cost is small as compared to the objective and sensitivity evaluation for a compliance problem. The scaling of the computational cost of the compliance evaluation (excluding the time spent on the overhang filter), the overhang filter, and the full sensitivity analysis related to the overhang filter, with respect to element number is plotted in Fig. 26. A power function is fitted to the measured CPU times, which are given for a single core computation on a 3.4Ghz Xeon E3-1240 V2. Compared to the compliance evaluation, which is primarily dominated by solving the system of linear equations, the overhang filter is significantly faster, and scales close to linear with the number of DOFs. Furthermore, it can be seen that the sensitivity calculation for the overhang filter is negligible in terms of computational cost.

Note that although the overhang filter sensitivity analysis only requires a single loop over all the nodes, it does not scale linearly. Because there are only few calculations in each iteration, the sensitivity calculation is memory bandwidth bound instead of compute-bound. In every iteration, non-contiguous entries of several arrays are accessed (see Algorithm 1), making it difficult for the compiler to load the correct part of the array to cache. Careful ordering of the arrays and prefetching are therefore important to control the scaling of the sensitivity analysis.

6 Conclusions

In this work a novel overhang filter based on front propagation is presented. Front propagation proves capable of detecting overhanging regions in a density-based topology by the use of an anisotropic speed function. By delaying the propagation in overhanging directions, a delay field can be constructed where overhanging regions have positive delay time while printable regions have 0 delay. This overhang detection procedure is incorporated as a filter into the topology optimization loop, and adjoint sensitivities are derived consistently. As such, the optimization algorithm can correct for unsupported regions by either removing or supporting them.

The Ordered Upwind Method is used to perform the front propagation, as it is computationally efficient and handles propagation with anisotropic speed functions. Furthermore, adjoint sensitivities are evaluated with a single loop over the elements, at low computational cost. The presented numerical results show various aspects of the overhang filter. It is shown that the overhang filter works for an arbitrary minimum overhang angle, that fully dense supports are generated when the volume constraint permits, and that the filter can handle unstructured meshes. In order to avoid inferior local optima, continuation is used. It is also observed that the supports that are generated are not always the shortest possible supports but sometimes “zigzag”. This is most likely related to the path of the sensitivities in the front propagation, and is a topic of further research.

Overall, the overhang filter performs well for the demonstrated 2D examples, and the front propagation is extensible to 3D as its formulation is mostly dimension independent. Although the specifics of the front propagation (Section 4.1) require adaptation for 3D, the Ordered Upwind Method will have the same computational complexity and hence the same scaling as the 2D algorithm evaluated in Section 5.8 (c.f. Fig. 26). In a practical setting, the complete removal of overhanging regions might not be necessary, but only in inaccessible locations. This also remains a topic of further research.

Finally, this paper introduces a new way to use front propagation algorithms within topology optimization. Because of the computational efficiency of the front propagation, it is an attractive algorithm to include in additional constraints or filters, if they can be modeled by a propagating front. Further research will focus on the use of front propagation to model more aspects of the printing process, and to include these into topology optimization.

References

Allaire G, Dapogny C, Estevez R, Faure A, Michailidis G (2017a) Structural optimization under overhang constraints imposed by additive manufacturing technologies. J Comput Phys 351(Supplement C):295–328

Allaire G, Dapogny C, Faure A, Michailidis G (2017b) Shape optimization of a layer by layer mechanical constraint for additive manufacturing. Compt R Math 355(6):699–717

Amestoy PR, Duff IS, L’Excellent JY, Koster J (2001) A fully asynchronous multifrontal solver using distributed dynamic scheduling. SIAM J Matrix Anal Appl 23(1):15–41

Amestoy PR, Guermouche A, L’Excellent JY, Pralet S (2006) Hybrid scheduling for the parallel solution of linear systems. Parallel Comput 32(2):136–156

Balay S, Gropp WD, McInnes LC, Smith BF (1997) Efficient management of parallelism in object oriented numerical software libraries. In: Arge E, Bruaset AM, Langtangen HP (eds) Modern Software Tools in Scientific Computing. Birkhȧuser Press, pp 163–202

Balay S, Abhyankar S, Adams MF, Brown J, Brune P, Buschelman K, Dalcin L, Eijkhout V, Gropp WD, Kaushik D, Knepley MG, McInnes LC, Rupp K, Smith BF, Zampini S, Zhang H, Zhang H (2016) PETSc Users Manual. Tech. Rep. ANL-95/11 - Revision 3.7, Argonne National Laboratory

Bendsoe M, Sigmund O (2003) Topology optimization: theory methods and applications. Engineering online library. Springer, Berlin

Brackett D, Ashcroft I, Hague R (2011) Topology optimization for additive manufacturing. In: Proceedings of the solid freeform fabrication symposium, Austin, pp 348–362

Bruns TE, Tortorelli DA (2001) Topology optimization of non-linear elastic structures and compliant mechanisms. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 190(26):3443–3459

Cloots M, Spierings A, Wegener K (2013) Assessing new support minimizing strategies for the additive manufacturing technology SLM. In: 24th International SFF Symposium - An Additive Manufacturing Conference, SFF, vol 2013, pp 631–643

Gaynor AT, Meisel NA, Williams CB, Guest JK (2014) Topology optimization for additive manufacturing: considering maximum overhang constraint. In: AIAA Aviation, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Gaynor AT, Guest JK (2016) Topology optimization considering overhang constraints: Eliminating sacrificial support material in additive manufacturing through design. Struct Multidiscip Optim 54(5):1157–1172

Guo X, Zhou J, Zhang W, Du Z, Liu C, Liu Y (2017) Self-supporting structure design in additive manufacturing through explicit topology optimization. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 323(Supplement C):27–63

Langelaar M (2016) Topology optimization of 3D self-supporting structures for additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf 12:60–70

Langelaar M (2017) An additive manufacturing filter for topology optimization of print-ready designs. Struct Multidisc Optim 55:871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-016-1522-2

Mirzendehdel AM, Suresh K (2016) Support structure constrained topology optimization for additive manufacturing. Comput-Aided Des 81:1–13

Qian X (2017) Undercut and overhang angle control in topology optimization: A density gradient based integral approach. Int J Numer Methods Eng 111(3):247–272. nme.5461

Sethian JA (1996) A fast marching level set method for monotonically advancing fronts. Proc Nat Acad Sci 93(4):1591–1595

Sethian J, Wiegmann A (2000) Structural boundary design via level set and immersed interface methods. J Comput Phys 163(2):489–528

Sethian JA, Vladimirsky A (2003) Ordered upwind methods for static Hamilton–Jacobi equations: Theory and algorithms. SIAM J Numer Anal 41(1):325–363

Sigmund O, Petersson J (1998) Numerical instabilities in topology optimization: a survey on procedures dealing with checkerboards, mesh-dependencies and local minima. Struct Optim 16(1):68–75

Sigmund O (2007) Morphology-based black and white filters for topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim 33(4):401–424

Stolpe M, Svanberg K (2001) An alternative interpolation scheme for minimum compliance topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim 22(2):116–124

Svanberg K (1987) The method of moving asymptotes – a new method for structural optimization. Int J Numer Methods Eng 24(2):359–373

Thomas D (2009) The development of design rules for selective laser melting. PhD thesis, University of Wales

van Keulen F, Hirai Y, Tabata O (2008) Objective function and adjoint sensitivities for Moving-Mask Lithography. In: 12th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis and Optimization Conference, p 5934

van de Ven E, Ayas C, Langelaar M, Maas R, van Keulen F (2018) A PDE-Based Approach to Constrain the Minimum Overhang Angle in Topology Optimization for Additive Manufacturing. In: Schumacher A, Vietor T, Fiebig S, Bletzinger KU, Maute K (eds) Advances in Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization: Proceedings of the 12th World Congress of Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization (WCSMO12). Springer, Cham, pp 1185–1199

Vladimirsky AB (2001) Fast methods for static Hamilton-Jacobi partial differential equations. PhD thesis, University of California

Wang D, Yang Y, Yi Z, Su X (2013) Research on the fabricating quality optimization of the overhanging surface in SLM process. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 65(9-12):1471–1484

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under project number S12.7.14549a in the framework of the Metals for Additive Manufacturing Partnership Program of the Materials innovation institute M2i (www.m2i.nl) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (www.nwo.nl). The authors thank Krister Svanberg for use of the MMA optimizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van de Ven, E., Maas, R., Ayas, C. et al. Continuous front propagation-based overhang control for topology optimization with additive manufacturing. Struct Multidisc Optim 57, 2075–2091 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-017-1880-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-017-1880-4